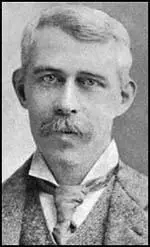

Charles E. Montague

Charles Edward Montague, the son of Francis Montague and Rosa McCabe was born on the 1st January, 1867. His father had been a Catholic priest but after falling in love with his future wife, the daughter of a successful merchant from Drogheda, he left the Church and in 1863 moved to England. Charles was educated at the City of London School and Balliol College, Oxford

While at university Montague wrote several literary reviews for the Manchester Guardian. In February, 1890, the editor,C. P. Scott, invited him to Manchester him a month's trial. Scott was impressed by Montague and soon gave him a full-time post.

Montague shared Scott's political views and together they turned the Manchester Guardian into a campaigning newspaper. The both believed that the main tenet was "to bring all political action to the same tests as personal conduct". This led the men to support Home Rule for Ireland and opposed the Boer War. Montague also wrote about the theatre and by the early 1900s was acknowledged as one of Britain's leading drama critics.

C. P. Montague eventually became assistant editor and played an important role in the development of the newspaper when C. P. Scott was a member of the House of Commons between 1895 and 1906. The bond between the two men was reinforced in 1898 by Montague marrying the editor's only daughter, Madeline Scott, at the Unitarian Chapel in Manchester.

Like C. P. Scott, Montague argued in the summer of 1914 against Britain becoming involved in a war with Germany. However, once war had been declared, Montague believed that it was important to give full support to the British government in its attempts to achieve victory. Montague wrote to Scott: "I have felt for some time, and especially since I have been writing leaders urging people to enlist, a strong wish to do the same myself. I wrote last week to the War Office to ask if there was any chance of getting over the difficulty of my few years over the limit of age, and I was told that although the War Office could not directly break the rule itself, it did not veto exceptions made by those responsible for the raising of new battalions locally."

Although forty-seven with a wife and seven children, Montague volunteered to join the British Army. Grey since his early twenties, Montague died his hair in an attempt to persuade the army to take him. On 23rd December, 1914, the Royal Fusiliers accepted him and he joined the Sportsman's Battalion.

After receiving military training at Climpson Camp in Nottingham, Montague went to France in November, 1915. The following month he wrote to Francis Dodd: "The one thing of which no description given in England any true measure is the universal, ubiquitous muckiness of the whole front. One could hardly have imagined anybody as muddy as everybody is. The rats are pretty well unimaginable too, and, wherever you are, if you have any grub about you that they like, they eat straight through your clothes or haversack to get at it as soon as you are asleep. I had some crumbs of army biscuit in a little calico bag in a greatcoat pocket, and when I awoke they had eaten a big hole through the coat from outside and pulled the bag through it, as if they thought the bag would be useful to carry away the stuff in. But they don't actually try to eat live humans."

When he arrived at the Western Front, his commanding officer questioned the wisdom of having a man in his late forties in the trenches. Montague was sent before the Medical Board and had to wait until the end of January, 1916, before being allowed to return to the trenches. However, three months later, a new ruling banned all men over forty-four from trench work.

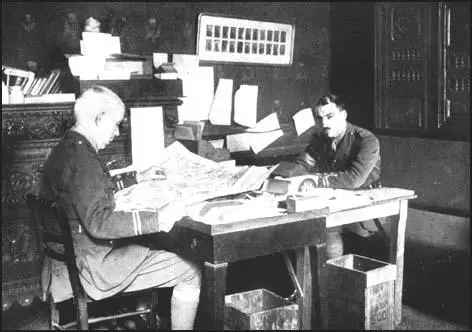

The journalist, Philip Gibbs, later recalled: "Prematurely white-haired, he had dyed it when the war began and had enlisted in the ranks. He became a sergeant and then was dragged out of his battalion, made a captain, and appointed as censor to our little group. Extremely courteous, abominably brave - he liked being under shell fire - and a ready smile in his very blue eyes, he seemed unguarded and open. Once he told me that he had declared a kind of moratorium on Christian ethics during the war. It was impossible, he said, to reconcile war with the Christian ideal, but it was necessary to get on with its killing. One could get back to first principles afterwards, and resume one's ideals when the job had been done."

Montague was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and transferred to Military Intelligence. For the next two years he had the task of writing propaganda for the British Army and censoring articles written by the five authorized English journalists on the Western Front (Perry Robinson, Philip Gibbs, Percival Phillips, Herbert Russell and Bleach Thomas). He also took important visitors for tours of the trenches. This included David Lloyd George, Georges Clemenceau, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells.

Montague became disillusioned with the First World War. He wrote in his diary in December 1917: "To take part in war cannot, I think, be squared with Christianity. So far the Quakers are right. But I am more sure of my duty of trying to win the war than I am that Christ was right in every part of all that he said, though no one has ever said so much that was right as he did. Therefore I will try, as far as my part goes, to win the war, not pretending meanwhile that I am obeying Christ, and after the war I will try harder than I did before to obey him in all the things in which I am sure he was right. Meanwhile may God give me credit for not seeking to be deceived."

George Bernard Shaw was one of those who Montague took for a tour of the frontline trenches: "At the chateau where the Army entertained the rather mixed lot who were classified as Distinguished Visitors, I met Montague. Finding him just the sort of man I like and get on with, I was glad to learn that he was to be my leader on my excursions. The standing joke about Montague was his craze for being under fire, and his tendency to lead the distinguished visitors, who did not necessarily share this taste into warm corners. Like most standing jokes it was inaccurate, but had something in it.... Both of us felt that, being there, we were wasting our time when we were not within range of the guns. We had come to the theatre to see the play, not to enjoy the intervals between the acts like fashionable people at the opera."

After the war Montague returned to the Manchester Guardian and stayed there until he retired in 1925. He also wrote several books including the novels A Hind Let Loose and Rough Justice, and a collection of essays, Disenchantment (1922) about the First World War. He argued: "The freedom of Europe, The war to end war, The overthrow of militarism, The cause of civilization - most people believe so little now in anything or anyone that they would find it hard to understand the simplicity and intensity of faith with which these phrases were once taken among our troops, or the certitude felt by hundreds of thousands of men who are now dead that if they were killed their monument would be a new Europe not soured or soiled with the hates and greeds of the old. So we had failed - had won the fight and lost the prize; the garland of war was withered before it was gained. The lost years, the broken youth, the dead friends, the women's overshadowed lives at home, the agony and bloody sweat - all had gone to darken the stains which most of us had thought to scour out of the world that our children would live in. Many men felt, and said to each other, that they had been fooled."

Charles Edward Montague died of 28th May, 1928.

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Montague, letter to his father (27th October, 1914)

At the office we begin to hear of colleagues who departed as second lieutenants in August now blossoming into captains and what not. One of our dramatic critics has got to the war as an interpreter, another man is driving a motor ambulance, several have enlisted, and all the rest want to be war correspondents. My own slender chance of ever seeing any of the fun depends on the remote possibility of Kitchener's accepting a battalion of 1000 fit and hardy old cocks of 45 or more, of whom I am one.

(2) Charles Montague, letter to C. P. Scott (24th November, 1914)

I have felt for some time, and especially since I have been writing leaders urging people to enlist, a strong wish to do the same myself. I wrote last week to the War Office to ask if there was any chance of getting over the difficulty of my few years over the limit of age, and I was told that although the War Office could not directly break the rule itself, it did not veto exceptions made by those responsible for the raising of new battalions locally.

(3) Soon after arriving at the Western Front, Montague wrote to his friend Francis Dodd (30th December, 1915)

The one thing of which no description given in England any true measure is the universal, ubiquitous muckiness of the whole front. One could hardly have imagined anybody as muddy as everybody is. The rats are pretty well unimaginable too, and, wherever you are, if you have any grub about you that they like, they eat straight through your clothes or haversack to get at it as soon as you are asleep. I had some crumbs of army biscuit in a little calico bag in a greatcoat pocket, and when I awoke they had eaten a big hole through the coat from outside and pulled the bag through it, as if they thought the bag would be useful to carry away the stuff in. But they don't actually try to eat live humans.

(4) In December 1915 Montague was judged to be too old to be in the front-line. Montague appealed against this decision and on 28th January 1916 had to appear before the Army Medical Board.

I went in and found the Colonel-Surgeon, who barred me a month ago on the ground of my age, again presiding. He looked up at me genially, when I came to the table, and said, "So I hear you want to have another whack of the Germans". I admitted that I did. "How old are you - I mean, your real age?" "Forty-nine, Sir", said I, "but only just". "Sure you're fit?" I said yes. Another doctor at the table said something about my having been there before. "Yes, yes", said the Colonel, "I remember him perfectly. Well, Sergeant, all right", and he marked me a big 'A' on his report. I grinned and saluted and made off. He called after me as I was making for the door, "Sergeant, I believe you'll do better up there than some of the young uns".

(5) Charles Montague, diary entry (December, 1917)

To take part in war cannot, I think, be squared with Christianity. So far the Quakers are right. But I am more sure of my duty of trying to win the war than I am that Christ was right in every part of all that he said, though no one has ever said so much that was right as he did. Therefore I will try, as far as my part goes, to win the war, not pretending meanwhile that I am obeying Christ, and after the war I will try harder than I did before to obey him in all the things in which I am sure he was right. Meanwhile may God give me credit for not seeking to be deceived.

(6) Philip Gibbs, The Pageant of the Years (1946)

One of the censors was C. E. Montague, the most brilliant leader writer and essayist on the Manchester Guardian before the war. Prematurely white-haired, he had dyed it when the war began and had enlisted in the ranks. He became a sergeant and then was dragged out of his battalion, made a captain, and appointed as censor to our little group. Extremely courteous, abominably brave - he liked being under shell fire - and a ready smile in his very blue eyes, he seemed unguarded and open.

Once he told me that he had declared a kind of moratorium on Christian ethics during the war. It was impossible, he said, to reconcile war with the Christian ideal, but it was necessary to get on with its killing. One could get back to first principles afterwards, and resume one's ideals when the job had been done.

(7) Charles Montague took George Bernard Shaw on a tour of the Western Front in January, 1917. Later, he wrote about the experience.

At the chateau where the Army entertained the rather mixed lot who were classified as Distinguished Visitors, I met Montague. Finding him just the sort of man I like and get on with, I was glad to learn that he was to be my leader on my excursions. The standing joke about Montague was his craze for being under fire, and his tendency to lead the distinguished visitors, who did not necessarily share this taste into warm corners. Like most standing jokes it was inaccurate, but had something in it. Neither of us ever asked the other "And what the devil are you doing in this gallery?" Both of us felt that, being there, we were wasting our time when we were not within range of the guns. We had come to the theatre to see the play, not to enjoy the intervals between the acts like fashionable people at the opera.

(8) Sir Beach Thomas, representing the Daily Mirror and Daily Mail, was one of the five authorized journalist on the Western Front. He later described the role of C. E. Montague during the war.

Montague once said that shell-fire gave him a mental stimulus that nothing else did. He also said, and he would not say a thing without meaning it, that he thought it would be a fine thing to be killed in this war. There can be no doubt that he definitely liked shell-fire at one time, though his nerves were a little frayed towards the end, largely because he was responsible for other people's safety. One particular journey with him, illustrating this side of his character, will always abide in my mind's eye.

We went to to see the Colonel of a battalion whose time was largely spent on repairing paths and duckboard paths, continually shelled to ribbons. The Colonel was one of those who so hated things, and the enemy, that he actually wished to be killed. His mind sank further and further into a slough of disgust as he worked day after day in the stinking mud of that continuous cemetery. He took us to the crown of the ridge: his Major, Montague, and me.

As we reached the top he pointed towards a hidden and distant German battery, and said, "If we stand here a minute they will begin to shell us." To his obvious delight they did, and very accurately. The Major, whose nerves were on edge, wisely retired to a shell-hole; and I followed with what deliberation I could muster.

The Colonel and Montague continued to stand talking on the ridge, stiff, obstinate silhouettes against a grey sky. The second shell fell short, half-way between us, and one great piece flew low, straight at the shell-hole. Montague did not stir. He was ideally happy, enjoying his mental stimulus; but, being very careful of other people, he induced the Colonel to retire slowly. The poor Colonel had to wait another month before the desired shell struck him.

(9) De Witt Mackenzie represented the Associated Press of America at the Western Front. He also commented on C. E. Montague's bravery under fire.

One finds difficulty in summing up Montague's complex characteristics. Had our friend lived a few hundred years ago he most certainly would have been a great explorer and discoverer. The times and circumstances made him an outstanding scholar and writer, but in his heart he was an adventurer. Never have I known another man who so loved to thrust himself into danger for the sake of the thrill he got from it. He was known as 'fire-eater' throughout the length of the British Front.

I shall remember to the end one trip with him into the zone of death during the never-to-be-forgotten Passchendaele push. The Germans had been driven back along the Roulers railway, and Montague and I decided that we would look the battlefield over. For hours we pushed forward through the frightful mud, making our perilously way between the huge, water-filled shell-holes which in many places almost interlocked. The German 5.9s were coming down about us like peas off a hot skillet. Everywhere was death and destruction. There was not a moment when we were not in danger of being blown to atoms. Frankly, I didn't like it, but Montague glorified in it. I had troubles of my own, but I watched him in fascination. His shoulders were squared, his head was thrown back, and his eyes were blazing with a strange fire. He was in the state of ecstasy - a man in a trance.

The real Montague didn't come to earth until we encountered a crisis. We finally reached a ridge, just back of the British advanced line, and so exposed to the enemy that we were shooting at our troops from shrapnel guns with open sights. We paused for a moment, and then Montague tossed his head like a charger and said: "Let's push on." We had barely resumed our journey when a piece of shrapnel hit my steel helmet. The metal rang like a church bell. For a bit I rocked about on my feet, wondering what had happened to me. Then I looked over at Montague. He was gazing at me with troubled eyes; he had come to earth again at last. "I think perhaps we have come a bit too far, Mackenzie," he said in his quiet way. 'Let's get under cover." He was thinking entirely of me. Shrapnel never worried him personally. However, we went over and sat down among the dead behind a concrete pill-box and rested. Then we started back home.

(10) Charles Montague, Disenchantment (1922)

Soldiers would serve a divisional tour of sixteen days' duty in the line. For four days the men would be in reserve under enemy fire, but not in trenches; probably in the cellars of ruined houses. But these were not times of rest. Each day or night every man would make one or more journeys back to the trenches that they had left carrying some load of food, water, or munitions up to the three companies in trenches, or perhaps leading a pack-mule over land to some point near the front line, under cover of night. Even to lead an laden mule in the dark over waste ground confusingly wired and trenched is work; to get him back on to his feet when fallen and wriggling, in wild consternation, among a tangle of old barbed wire may be quite hard work.

After four days of their labours as sumpter mules, or muleteers, the company would plod back for another four days of duty in trenches, come out yet more universally tired at their end, and drift back to rest-billets, out of ordinary shell-fire, for their sixteen days or so of 'divisional rest'.

(11) Charles Montague, Disenchantment (1922)

The war had more obvious disagreeables, too, you have heard all about them: the quelling coldness of frosty nights spent in soaked clothes - for no blankets were brought up to the trenches; the ubiquitous dust and stench of corpses and buzzing of millions of corpse-fed flies on summer battlefields; and so on, and so on.

(12) Charles Montague, letter to his wife (5th November, 1917)

After the war I believe there will be less ill-will against Germans in general among our returning soldiers than among any other equal number of men at home, just because hard fighting, man against man, tends to let off bitterness and make you regard your opponent as a kind of other side in an athletic contest. In intervals in some of our recent battles there have been quite exemplary spectacles of honourable fighting - stretcher-bearers of both sides, out in No Man's Land in crowds, sorting out their respective wounded, and nobody firing a shot at them.

(13) Charles Montague, diary entry (29th March, 1918)

With Philip Gibbs and Hamilton Fyfe to No. 3 Canadian C.C.S. in the Vauban Citadel, Doullens. Great smell of blood everywhere. Casualties coming in freely. 2,500 evacuated yesterday. 20,000 dealt with in last 8 days. Some of the cases mere bundles of cloth, mud, blood, and torn meat. Unpacked carefully by nurses, who despair of nothing still warm. While Gibbs and Fyfe circulate and question and take notes among walking wounded, an ambulance driver and a wounded Australian sergeant successively draw my attention to them as possible spies.

(14) De Witt Mackenzie, an America newspaper reporter, recalled an incident that took place during the First World War.

Several of us, including Montague, were seated at a table one day. Fierce fighting was going on at the time, and everybody's nerves were on the ragged edge. Because of this there was a good deal of pessimism in the air. Somebody remarked:

"The whole world's gone crazy with the war lust." Nobody answered except Montague, who looked up with a whimsical smile and a questioning "Yes?"

"Yes", affirmed the other. "Mankind has sunk below the level of swine and is glorying as it wallows in the mire. Christianity is as dead as a door nail, and men are going out to slaughter one another for the pure joy of killing. There isn't a spark of mercy left in the human breast."

"I saw an incident up at the front today that might interest you", responded Montague. "While I was standing at an emergency in to receive attention. He was leading a German prisoner, who also was wounded - just a boy, of seventeen or so. I was interested in the queer pair and inquired about them. Tommy had been in a hot fight, and had already accounted for three or four of the enemy when he came upon the youngster. The boy was frightened, but he managed to shoot Tommy through an arm, and then prepared to use his bayonet as Tommy charged."

"Tommy undoubtedly was seeing red by this time, and was as near to the brute stage as he ever would get. He had been fighting hand-to-hand; he had killed, and now he was facing another who was trying to kill him. But instead of using his own rifle or bayonet, he closed on the German lad and disarmed him. Somebody asked Tommy why he hadn't killed the German.

"You see, sir," apologized Tommy, "he was such a little begger I didn't have the heart to do it."

That was all; there was no further argument at the table; indeed, there was nothing more to argue about. It was Montague's way of handling a situation. And it revealed again the bigness of his heart and the breadth of his understanding.

(15) Charles Montague, diary entry (2nd October, 1918)

Lovely, these days, to see Amiens taking life again. They are said to be 10,000 people back, out of about 120,000. Everywhere windows are being mended, and in some places brickwork; a few more shops and restaurants are opened every day and one notices more people in the streets; the shell-hole in my old bedroom in the Ecu de France is mended already, and one passenger train a day goes through the station each way. There are no police, no gas no electric light. In the slums, where I took a walk last night, there is a grim gloom such as I imagine at night in mediaeval cities. On the shutters of some of the closed shops are notices, "Any British soldier looting will be shot", and in many of the deserted shops one can see wares of some value through the windows. But there is an exhilaration about the beginning of revival, like the renewal of youth that one feels when recovering from illness.

(16) Charles Montague, diary entry (3rd October, 1918)

German cemetery with between 1300 and 1400 graves. Of those of 1914-16 are massive stone blocks and crosses. On those of 1917, heavy wooden crosses. On those of 1918, scraggy wood crosses, and they are huddled closer. The graves recede from the road, in order of date, and that the graduation is solidly clear and expressive.

(17) Charles Montague, letter to Francis Dodd (18th November, 1918)

It has been a wonderful progress eastwards, always coming into new towns and villages where the people rushed out, and shook hands and kissed us and sometimes offered us pieces of bread, thinking we must be half-starved like themselves and the German troops.

When the war ended I had the luck to be at our front at the very place from which the old army was forced to retreat in 1914, and it was great when eleven o'clock went and the Belgian civilians and we crowded together into the village square to rejoice. They played 'Tripperay' on the parish church bells and we all sang the two National Anthems and cheered King Albert and felt it had all been worthwhile.

The day after the fighting ended I met hundreds of men who had been prisoners and broken out just before the armistice. They were coming back into our lines, almost starving, and some of them had died of hunger and exhaustion on the way; but they came along splendidly, marching in little groups under the command of the oldest soldier in each, with their horrible black uniforms as clean and neat as hard trying could make them, marching along very steady and smart and taking no notice of anybody. I thought I had never seen the British soldier to greater advantage.

(18) Charles Montague, Disenchantment (1922)

Soldiers have endless occasions for talk. Being seldom alone, and having to hold their tongues sometimes, they talk all the time with that they can. And most of their talk was sour and scornful.

Most of the N.C.O.'s and men in the field had come to feel that it was left to them and to the soundest regimental officers to pull the foundered rulers of England and heads of the army through the scrape. They assumed now that while they were doing this job they must expect to be crawled upon by all the vermin bred in the dark places of a rich country vulgarly governed.

They were well on their guard by this time against expressing any thoroughgoing faith in anything or anybody, or incurring any suspicion of dreaming that such a faith was likely to animate others; a man was a fool if he imagined that anyone set over him was not looking after number one; the patriotism of the press was bunkum, screening all sorts of queer games; the eloquence of patriotic orators was just a smoke barrage to cover their little manoeuvres against one another.

The lions felt they had found out the asses. They would not try to throw off the lead of the asses just then; you cannot reorganize a fire-brigade in the midst of a fire. They had to wait.

(19) Charles Montague, Disenchantment (1922)

"The freedom of Europe," "The war to end war," "The overthrow of militarism," "The cause of civilization" - most people believe so little now in anything or anyone that they would find it hard to understand the simplicity and intensity of faith with which these phrases were once taken among our troops, or the certitude felt by hundreds of thousands of men who are now dead that if they were killed their monument would be a new Europe not soured or soiled with the hates and greeds of the old.

So we had failed - had won the fight and lost the prize; the garland of war was withered before it was gained. The lost years, the broken youth, the dead friends, the women's overshadowed lives at home, the agony and bloody sweat - all had gone to darken the stains which most of us had thought to scour out of the world that our children would live in. Many men felt, and said to each other, that they had been fooled.

(20) In his book Father Figures, Kingsley Martin, a fellow leader writer at the Manchester Guardian, wrote about working with C. E. Montague.

In spite of my great admiration for him I could not get to know him much. He was the most shy of men; he vainly went to football matches hoping to get in touch with the common herd. He wrote a revealing essay about the art of writing, one good novel, A Hind Let Loose, about the press, some fine dramatic criticism, leading articles that might bear republishing, and one of the best of all war books, Disenchantment.