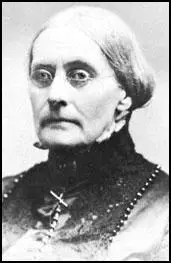

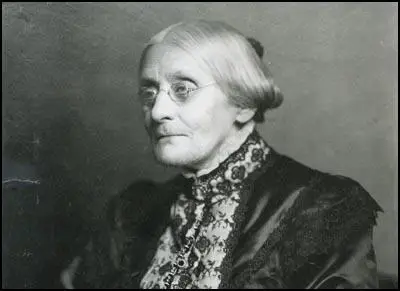

Susan Anthony

Susan Brownell Anthony, the daughter of Daniel Anthony, a cotton manufacturer, was born in Adams, Massachusetts, on 15th February, 1820. Her father was a Quaker who campaigned against the slave trade.

After an education at her father's school and a Philadelphia boarding school, she began teaching at a female academy near Rochester, New York.

In 1852 Anthony joined with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer in campaigning for women's suffrage and equal pay. Anthony also became involved in the campaign for prohibition and was active in the American Anti-Slavery Society and helped escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad.

During the American Civil War Anthony strongly supported the Union cause. She also aided the administration of President Abraham Lincoln by forming the Women's Loyal League. In 1866 Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and Lucy Stone established the American Equal Rights Association. The following year, the organisation became active in Kansas where Negro suffrage and women's suffrage was to be decided by popular vote. However, both ideas were rejected at the polls. In 1868 Anthony and Stanton founded the political weekly, The Revolution.

In 1869 Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton formed a new organisation, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The organisation condemned the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments as blatant injustices to women. The NWSA also advocated easier divorce and an end to discrimination in employment and pay. Anthony toured the country making speeches on women's rights. In one year alone, she travelled 13,000 miles and made over 170 speeches. In 1872 Anthony attempted to vote in a an election in Rochester. She was arrested, charged and later found guilty of violating voting rights.

Another group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), was also active in the campaign for women's rights and by the 1880s it became clear that it was not a good idea to have two rival groups campaigning for votes for women. After several years of negotiations, the AWSA and the NWSA merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Elizabeth Cady Stanton became the NAWSA's first president, but Anthony took over in 1892 and held the post for the next eight years.

Anthony was also a historian and with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, she complied and published the four volume, The History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1902).

Susan Brownell Anthony died on 13th March, 1906.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Primary Sources

(1) Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, History of Woman Suffrage (1881)

Susan B. Anthony, having been a successful teacher in the State of New York fifteen years of her life, had seen the need of many improvements in the mode of teaching and in the sanitary arrangements of school buildings.

In 1853, the annual (education) convention being held in Rochester, her place of residence. Miss Anthony conscientiously attended all the sessions through three entire days. After having listened for hours to a discussion as to the reason why the profession of teacher was not as much respected as that of the lawyer, minister, or doctor, without once, as she thought, touching the kernel of the question, she arose to untie for them the Gordian knot, and said, "Mr. President." If all the witches that had been drowned, burned, and hung in the Old World and the New had suddenly appeared on the platform, threatening vengeance for their wrongs, the officers of that convention could not have been thrown into greater consternation.

At length President Davies, of West Point, in full dress, buff vest, blue coat, gilt buttons, stepped to the front, and said in a tremulous, mocking tone, "What will the lady have?" "I wish, sir, to speak to the question under discussion," Miss Anthony replied. The Professor, more perplexed than before, said: "What is the pleasure of the Convention?" A gentleman moved that she should be heard; another seconded the motion; whereupon a discussion pro and con followed, lasting full half an hour, when a vote of the men only was taken, and permission granted by a small majority; and lucky for her, too, was it, that the thousand women crowding that hall could not vote on the question, for they would have given a solid "no." The president then announced the vote, and said: "The lady can speak."

We can easily imagine the embarrassment under which Miss Anthony arose after that half hour of suspense, and the bitter hostility she noted on every side. However, with a clear, distinct voice, which filled the hall; she said: "It seems to me, gentlemen, that none of you quite comprehend the cause of the disrespect of which you complain. Do you not see that so long as society says a woman is incompetent to be a lawyer, minister, or doctor, but has ample ability to be a teacher, that every man of you who chooses this profession tacitly acknowledges that he has no more brains than a woman? And this, too, is the reason that teaching is a less lucrative profession, as here men must compete with the cheap labor of woman. Would you exalt your profession, exalt those who labor with you. Would you make it more lucrative, increase the salaries of the women engaged in the noble work of educating our future Presidents, Senators, and Congressmen."

This said, Miss Anthony took her seat, amid the profoundest silence, broken at last by three gentlemen, walking down the broad aisle to congratulate the speaker on her pluck and perseverance. . .

To give the women of today some idea of what it cost those who first thrust themselves into these conventions at the close of the session Miss A. heard women remarking: "I was actually ashamed of my sex." "I felt so mortified I really wished the floor would open and swallow me up." "Who can that creature be?" "She must be a dreadful woman to get up that way and speak in public."

Miss Anthony attended these teachers' conventions from year to year, at Oswego, Utica, Poughkeepsie, Lockport, Syracuse, making the same demands for equal place and pay, until she had the satisfaction to see every right conceded. Women speaking and voting on all questions; appointed on committees, and to prepare reports and addresses, elected officers of the Association, and seated on the platforms. In 1856, she was-chairman of a committee herself, to report on the question of co-education; and at Troy, she read her report, which the press pronounced able and conclusive. The President, Mr. Hazeltine, of New York, congratulating Miss Anthony on her address, said: "As much as I am compelled to admire your rhetoric and logic the matter and manner of your address and its delivery I would rather follow a daughter of mine to her grave, than to have her deliver such an address before such an assembly ".

Superintendent Randall, overhearing the President, added: I should be proud, Madam, if I had a daughter capable of making such an eloquent and finished argument, before this or any assembly of men and women. I congratulate you on your triumphant success."

(2) Ida Wells played an active role in the women suffrage movement. In her book, Crusade for Justice (1928), she described a conversation she had with Susan Anthony about Frederick Douglass.

Miss Anthony said when women called their first convention back in 1848 inviting all those who thought that women ought to have an equal share with men in the government, Frederick Douglass, the ex-slave, was the only man who came to their convention and stood up with them. He said he could not do otherwise; that we were among the friends who fought his battles when he first came among us appealing for our interest in the antislavery cause. From that day until the day of his death Frederick Douglass was an honorary member of the National Women's Suffrage Association. In all our conventions, most of which had been held in Washington, he was the honored guest who sat on our platform and spoke in our gatherings.

(3) Editorial, Time and Tide (9th July, 1926)

Feminism, like any other great movement, proceeds at varying paces and in varying forms in different countries. Few things are more enlightening than a study of the inter-reactions of the feminist movement in the two great English speaking peoples during the past seventy or eighty years. It is curious how closely related have been the movements on the two sides of the Atlantic. Each has continually learnt from the other. Beginning with Mary Wollstonecraft in the late 18th century, the feminist movement owed its next big impetus (in the eighteen forties and fifties) to Lucretia Mott and Susan B. Anthony, of New England. It was Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth C. Stanton who organised the first Equal Rights Convention which was held in New York in 1848; and it was Lucretia Mott who laid down the definite proposition which American women are still struggling to implement today: "Men and Women shall have Equal Rights throughout the United States." A few years later Susan B. Anthony, the pioneer Suffragist, came into the American movement.

It was not till the eighteen sixties that the political feminist movement came alive in Great Britain. Dame Millicent Fawcett was even in those early days one of the leading names connected with it. The British suffragists pushed forward enthusiastically for some twenty years, but the failure to achieve success in 1885, when the third Reform Bill was passed giving the agricultural labourer the vote, seemed to take the heart out of our early suffragists, and the movement died down again. Meanwhile, in the nineties the American women were full of life and enthusiasm, winning victory after victory in State after State.'

In 1902 Susan B. Anthony came to England and stayed with Mrs. Pankhurst in Manchester. The result of that visit was far-reaching. All unwittingly the old pioneer handed back the torch to the British suffragists. "It is unendurable," declared Christabel Pankhurst after her departure, "to think of another generation of women wasting their lives begging for the vote. We must not lose any more time. We must act." Those words heralded the birth of the British militant movement. From that moment onwards British feminists went forward without pause till the outbreak of war in 1914 and when that time came (although the actual Bill was not passed until 1918) the first installment of victory was virtually won.

Meanwhile in America by 1912 things had died down to very much the same state as the English movement has been in since 1918. Votes had been achieved in a considerable number of States, the feeling was widespread that a partial victory was good enough for the moment and that complete victory would ' come all in good time without much further trouble. And then in 1912 Alice Paul, lit by the fire of the English militant movement, returned to America - and America woke up. It took the Americans just eight years from that date to achieve complete political equality; but they were under wise leadership (Alice Paul will surely go down to history as one of the great leaders of the world), and when they did achieve political equality they did not make the mistake of supposing that that was the end. They turned back to the 'declaration of sentiments' laid down by Lucretia Mott in 1848 and they realised that political equality was only the first step on the path which they had chosen and that there could be neither halting nor relaxing their pace until they had come to the end of that path.