Prohibition

The prohibition movement in the United States began in the early 1800s and by 1850 several states had passed laws that restricted or prevented people drinking alcohol. Early campaigners for prohibition included William Lloyd Garrison, Frances E. Willard, Anna Howard Shaw, Carry Nation, Mary Lease and Ida Wise Smith.

Neal Dow, a prosperous businessman in Portland, Maine, established the Young Men's Abstinence Society. He also led the campaign that resulted in Maine passing the nation's first prohibition law in 1846.

During the 19th century, two powerful pressure groups, the Anti-Saloon League and the Women's Christian Temperance Union were established in America. In 1869 members of the temperance movement formed the Prohibition Party. Three years later James Black of Pennsylvania became the party's candidate for the presidency. However he won only 5,608 votes.

In 1879 John St. John was elected governor of Kansas. Four years later he succeeded in making Kansas the first state to outlaw alcohol by constitutional amendment. This action made him the hero of the temperance movement and in 1884 the Prohibition Party chose St. John as their presidential candidate.

St. John won only 150,369 votes in the election but it was a great improvement on previous candidates. He also took valuable votes from the Republican Party candidate, James Blaine, and helped Grover Cleveland of the Democratic Party to win victory. Cleveland was the first Democrat to become president since the Civil War. One newspaper described him as a "Judas Iscariot" and Republicans in over a hundred towns burned his effigy.

Other presidential candidates included Clinton Bowen Fisk (1888 - 249,506), John Bidwell (1892 - 264,133), Joshua Levering (1896 - 132,007), John Granville Woolley (1900 - 208,914), Silas Comfort Swallow (1904 -258,536), Eugene Wilder Chafin (1908 - 253,840 and 1912 - 206,275) and James Franklin Hanly (1916 - 220,506).

During the First World War most people considered it to be unpatriotic to use much needed grain to produce alcohol. Also, several of the large brewers and distillers were of German origin. Many business leaders believed their workers would be more productive if alcohol could be withheld with them. John D. Rockefeller, alone, donated over $350,000 to the Anti-Saloon League.

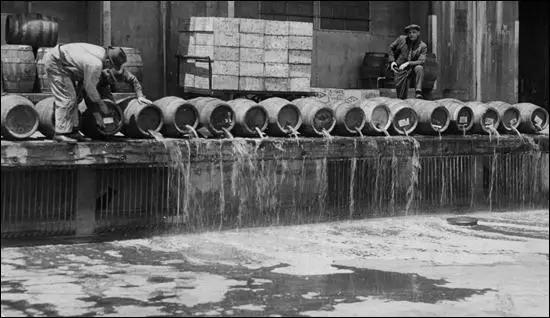

Opinion on prohibition began to change and by January, 1919, 75% of the states in America had approved the 18th Amendment which prohibited the "sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors". This became the law of the land when the Volstead Act was passed in 1920.

One of the consequences of the National Prohibition Act was the development of gangsterism and crime. Enforcement of prohibition was a difficult task and a growth in illegal drinking places took place. People called moonshiners distilled alcohol illegally. Bootleggers sold the alcohol and also imported it from abroad. The increase in criminal behaviour caused public opinion to turn against prohibition.

In the 1932 Presidential Election, the Democratic Party candidate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, promised an early end to prohibition. In February 1933, Congress voted to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment. While the Twenty-first Amendment was making its way through the states, Roosevelt requested quick action to amend the Volstead Act by legalizing beer of 3.2 per cent alcoholic content by weight. Within a week both houses passed the beer bill, and added wine for good measure. On 22nd March 1933, Roosevelt signed the bill.

William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), commented: "On April 7, 1933, beer was sold legally in America for the first time since the advent of prohibition, and the wets made the most of it. In New York, six stout brewery horses drew a bright red Busch stake wagon to the Empire State Building, where a case of beer was presented to Al Smith (the defeated Democratic candidate who opposed prohibition in 1928). In the beer town of St. Louis, steam whistles and sirens sounded by midnight, while Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee was blocked by mobs of celebrants standing atop cars and singing Sweet Adeline."

Primary Sources

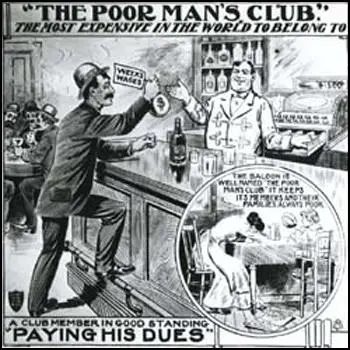

(1) Ernest Moore, The Social Value of the Saloon (July, 1897)

The saloonkeeper is the only man who keeps open house in the ward. It is his business to entertain. It does not matter that he does not select his guests; that convention is useless among them. In fact, his democracy is one element of his strength. His face is the common meeting ground of his neighbors - and he supplies the stimulus which renders social life possible; there is an accretion of intelligence that comes to him in his business. He hears the best stories. He is the first to get accurate information as to the latest political deals and social mysteries. The common talk of the day passes through his ears and he is known to retain that which is the most interesting.

There is another primal need which the saloon supplies and in most cases supplies well. It is a food-distributing centre - a place where a hungry man can get as much as he wants to eat and drink for a small price. As a rule the food is notoriously good and the price notoriously cheap. That the saloon feeds thousands and feeds them well no one will deny who has passed the middle of the day there.

It is hardly necessary to enlarge further upon the evils of the saloon. They are many and grave, and cry out to society for proper consideration. But proper consideration involves a whole and not a half truth, and the whole truth involves its own power of proper action. In the absence of higher forms of social stimulus and larger social life, the saloon will continue to function in society, and for that great part of humanity which does not possess a more adequate form of social expression.

(2) Roy Haynes, speech to the Women's Christian Temperance Union (26th January, 1927)

We must remember that prohibition is the greatest effort for human advancement and betterment ever attempted in history, and that while the nearest approach, perhaps, was the destruction of human slavery, let us not forget that that revolutionary policy affected only one section of the nation - whereas the national prohibition policy called for changing the habits and customs of the people in all sections of the nation.

Therefore, the most gratifying and enheartening feature of the situation is that so large a majority of our people respect the Constitution and observe this law, and this in spite of the fact that there is a very considerable number of citizens of influence and position who, by nonobservance, are embarrassing the government in the promotion of its great task.

But what has the experience of these seven years taught us? We have learned: (1) size of the task; (2) power of propaganda; (3) inadequacy of our legislation; (4) not enough emphasis on observance; (5) who are the friends and who are the foes, and the real plans of the latter; (6) in spite of all, real progress is being achieved; (7) how to measure progress.

That is, in brief, my summary of the outstanding lessons learned in these seven years. That is the retrospect. What of the prospect for the future?

Our campaign for the immediate future must be based upon the acknowledgment of but one statement of the whole issue, namely - Is the nation able to enforce its own laws - its own charter - in the face of an unsympathetic and actively hostile minority?

(3) Felix von Luckner, a German visitor to the United States, wrote about his thoughts on Prohibition in 1927.

My first experience with the ways of Prohibition came while we were being entertained by friends in New York. It was bitterly cold. My wife and I rode in the rumble seat of the car, while the American and his wife, bundled in furs, sat in front. Having wrapped my companion in pillows and blankets so thoroughly that only her nose showed, I came across another cushion that seemed to hang uselessly on the side. "Well," I thought, "this is a fine pillow; since everyone else is so warm and cozy, I might as well do something for my own comfort. This certainly does no one any good hanging on the wall." Sitting on it, I gradually noticed a dampness in the neighborhood, that soon mounted to a veritable flood. The odor of fine brandy told me I had burst my host's peculiar liquor flask.

In time, I learned that not everything in America was what it seemed to be. I discovered, for instance, that a spare tire could be filled with substances other than air, that one must not look too deeply into certain binoculars, and that the Teddy Bears that suddenly acquired tremendous popularity among the ladies very often had hollow metal stomachs.

"But," it might be asked, "where do all these people get the liquor?" Very simple. Prohibition has created a new, a universally respected, a well-beloved, and a very profitable occupation, that of the bootlegger who takes care of the importation of the forbid- den liquor. Everyone knows this, even the powers of government. But this profession is beloved because it is essential, and it is respected because its pursuit is clothed with an element of danger and with a sporting risk. Now and then one is caught, that must happen pro forma, and then he must do time or, if he is wealthy enough, get someone to do time for him.

Yet it is undeniable that Prohibition has in some respects been signally successful. The filthy saloons, the gin mills which formerly flourished on every corner and in which the laborer once drank off half his wages, have disappeared. Now, he can instead buy his own car and ride off for a weekend or a few days with his wife and children in the country or at the sea. But, on the other hand, a great deal of poison and methyl alcohol has taken the place of the good old pure whiskey.

The number of crimes and misdemeanors that originated in drunkenness has declined. But, by contrast, a large part of the population has become accustomed to disregard and to violate the law without thinking. The worst is, that precisely as a consequence of the law, the taste for alcohol has spread ever more widely among the youth. The sporting attraction of the forbidden and the dangerous leads to violations. My observations have convinced me that many fewer would drink were it not illegal.

And how, it will be asked, did this law get onto the statute books? Through the war. In America there was long a well-developed temperance movement and many individual states already had Prohibition laws. During the war it was not difficult to extend the force of those laws to the whole of the United States. Prohibition was at first introduced only for the period of the war. For the mass of the people it was very surprising when Congress in 1920 adopted the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which made it a crime to manufacture, transport, or sell intoxicating liquor. The dry states had imposed their will on the whole Union.

(4) Jack London, John Barleycorn (1913)

I achieved a condition in which my body was never free from alcohol. Nor did I permit myself to be away from alcohol. If I travelled to out-of-the-way places, I declined to run the risk of finding them dry. I took a quart, or several quarts, along in my grip. I was carrying a beautiful alcoholic conflagration around with me. The thing fed on its own heat and flamed the fiercer. There was no time in all my waking time, that I didn't want a drink.

(5) The autobiographical novel about alcoholism, John Barleycorn, was used by the Women's Christian Temperance Union, to promote their campaign. Upton Sinclair later remarked on the irony of the situation.

That the work (John Barleycorn) of a drinker (Jack London) who had no intention of stopping drinking should become a major propaganda piece in the campaign for Prohibition is surely one of the ironies in the history of alcohol.

(6) Art McGinley, talking about Eugene O'Neill in the 1920s.

Gene was a periodic drinker, and once started wouldn't stop - I guess he couldn't stop - until he was really sick. He was the most trying morning-after drinker I've ever known. He would gloom up and not say a word, or else talk of suicide, he was so disgusted with himself. But when he stopped drinking, he would work around the clock. I never knew anyone who had so much self-discipline.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929

Women in the United States in the 1920s

Subjects