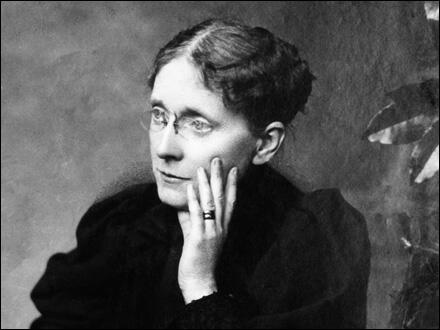

Frances Willard

Frances Willard, the daughter of a schoolteacher, was born in Churchville, New York, on 28th September, 1839. She studied at the Northwestern Female College, Evanston, Illinois and afterwards taught science at Pittsburgh Female College and Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in New York.

In 1871 Willard was appointed president of Northwestern Female College and when it merged with the university, she became college dean and professor of esthetics. Willard also worked as a journalist and for a time was editor of the Chicago Daily Post.

In 1874 Willard helped establish the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The main objective of the WCTU was to persuade all states to prohibit the sale of alcoholic beverages. Under the leadership of Willard (1879-1898), the organisation succeeded in bringing about temperance education in schools. The WCTU also supported the abolition of prostitution, prison reform and women's suffrage.

By 1881 Willard had become president of the WCTU. She was an outstanding lecturer, organizer, writer and for a time was editor of the Chicago Daily Post. Willard published her autobiography, Glimpses of Fifty Years, in 1889.

Williard became a socialist and in 1897 she shocked fellow delegates at the national conference of the Women's Christian Temperance Union when she argued that "socialism is the higher way; it enacts into everyday living the ethics of Christ's gospel. Nothing else will do."

Frances Willard developed Influenza while visiting New York City and died on 17th February, 1898.

Primary Sources

(1) Francis Willard, journal entry during the presidential campaign of John C. Fremont in 1856.

This is election day and my brother is twenty-one years old. How proud he seemed as he dressed up in his best Sunday clothes and drove off in the big wagon with father and the hired men to vote for John C. Fremont, like the sensible "Free-soiler" that he is. My sister and I stood at the window and looked out after them. Somehow, I felt a lump in my throat, and then I could not see their wagon any more, things got so blurred. I turned to Mary, and she, dear little innocent, seemed wonderfully sober, too. I said, "Wouldn't you like to vote as well as Oliver? Don't you and I love the country just as well as he, and doesn't the country need our ballots?" Then she looked scared, but answered, in a minute, " 'Course we do, and 'course we ought, - but don't you go ahead and say so, for then we would be called strong-minded."