The Volstead Act

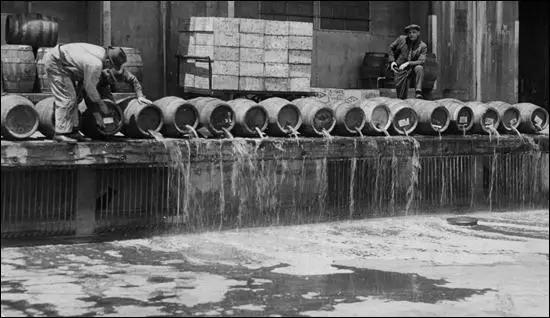

Andrew Volstead, a leading Republican member of the House of Representatives, was the author of the National Prohibition Act (also known as the Volstead Act) that was passed by Congress in 1919. The law prohibited the manufacture, transportation and sale of beverages containing more than 0.5 per cent alcohol. The act was condemned by a large number of the American population who considered it a violation of their constitutional rights.

As Frederick Lewis Allen pointed out: "The Government provided a force of prohibition agents which in 1920 numbered only 1,520 men and as late as 1930 numbered over 2,836. The agents' salaries in 1920 mostly ranged between $1,200 and $2,000; by 1930 they had been munificently raised to range between $2,300 and $2,800. Anybody who believed that men employable at 35 to 40 or 50 dollars a week would surely have the expert technical knowledge and the diligence to supervise successfully the complicated chemical operations of industrial-alcohol plants or to outwit the craftiest devices of smugglers to resist corruption by men whose pockets were bulging with money, would be ready to believe also in Santa Claus, perpetual motion and pixies."

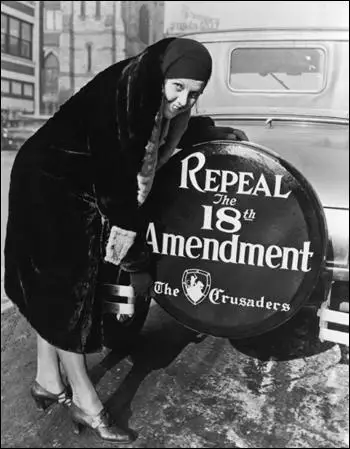

One of the consequences of the National Prohibition Act was the development of gangsterism and crime. Enforcement of prohibition was a difficult task and a growth in illegal drinking places took place. People called moonshiners distilled alcohol illegally. Bootleggers sold the alcohol and also imported it from abroad. The increase in criminal behaviour caused public opinion to turn against prohibition. In 1933 prohibition was repealed by the adoption of the 21st Amendment.

In the 1932 Presidential Election, the Democratic Party candidate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, promised an early end to prohibition. In February 1933, Congress voted to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment. While the Twenty-first Amendment was making its way through the states, Roosevelt requested quick action to amend the Volstead Act by legalizing beer of 3.2 per cent alcoholic content by weight. Within a week both houses passed the beer bill, and added wine for good measure. On 22nd March 1933, Roosevelt signed the bill.

William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), commented: "On April 7, 1933, beer was sold legally in America for the first time since the advent of prohibition, and the wets made the most of it. In New York, six stout brewery horses drew a bright red Busch stake wagon to the Empire State Building, where a case of beer was presented to Al Smith (the defeated Democratic candidate who opposed prohibition in 1928). In the beer town of St. Louis, steam whistles and sirens sounded by midnight, while Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee was blocked by mobs of celebrants standing atop cars and singing Sweet Adeline."

Primary Sources

(1) Pauline Sabin, Outlook Magazine (8th June, 1928)

I was one of the women who favoured prohibition when I heard it discussed in the abstract, but I am now convinced it has proved a failure. It is true we now longer see the corner saloon: but in many cases has it not merely moved to the back of a store, or up or down one flight (of stairs) under the name of a speakeasy? It is not true that they are making their own gin and drinking it furtively in their own rooms?

(2) Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday (1931)

The Government provided a force of prohibition agents which in 1920 numbered only 1,520 men and as late as 1930 numbered over 2,836. The agents' salaries in 1920 mostly ranged between $1,200 and $2,000; by 1930 they had been munificently raised to range between $2,300 and $2,800. Anybody who believed that men employable at 35 to 40 or 50 dollars a week would surely have the expert technical knowledge and the diligence to supervise successfully the complicated chemical operations of industrial-alcohol plants or to outwit the craftiest devices of smugglers to resist corruption by men whose pockets were bulging with money, would be ready to believe also in Santa Claus, perpetual motion and pixies.

(3) Alec Wilder, interviewed by Studs Terkel in Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (1970)

I loved speak-easies. If you knew the right ones, you never worried about being poisoned by bad whisky. I'd kept hearing about a friend of a friend who had been blinded by bad gin. I guess I was lucky. The speaks were so romantic. It had that marvellous movie-like quality, unreality. And the food was great. Although some pretty dreadful things did occur in them.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929

Women in the United States in the 1920s

Subjects