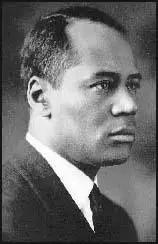

Charles Houston

Charles Houston was born in Washington on 3rd September, 1895. After studying at Dunbar High School, Amherst College and Harvard University Law School he became a university lecturer.

In July, 1935, Walter Francis White recruited Houston, to establish a legal department for the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). In a speech in P he argued: "The race problem in the United States is the type of unpleasant problem which we would rather do without but which refuses to be buried. It has been a visible or invisible factor in almost every important question of domestic policy since the foundation of the Government, and may yet be the decisive factor in the success or failure of the New Deal. The dominant interests in the South are determined that there shall not be an industrial emancipation of the Negro. In Birmingham, Alabama, on April 18, one brass-lunged industrialist raised the threat of secession of the Government persisted in its efforts to eliminate the wage differentials between the North and South."

In 1936 Houston appointed Thurgood Marshall as his assistant. Over the next few years Houston and Marshall used the courts to challenge racist laws concerning transport, housing and education.

Houston was also professor of law and later dean of Howard University Law School. Charles Houston died on 20th April, 1950.

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Houston, National YWCA Convention, Philadelphia (5th May, 1934)

The race problem in the United States is the type of unpleasant problem which we would rather do without but which refuses to be buried. It has been a visible or invisible factor in almost every important question of domestic policy since the foundation of the Government, and may yet be the decisive factor in the success or failure of the New Deal. The dominant interests in the South are determined that there shall not be an industrial emancipation of the Negro. In Birmingham, Alabama, on April 18, one brass-lunged industrialist raised the threat of secession of the Government persisted in its efforts to eliminate the wage differentials between the North and South....

In the field of agriculture the government cotton acreage reduction program of 1933 brought a conflict in interest between the plantation owners and their predominantly Negro sharecroppers and tenant farmers. The Southern Commission on the Study of Lynching in its report "The Plight of Tuscaloosa", found that out of 6,000 government checks sent into Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, as compensation for the cotton acreage reduction, only 115 were made out to Negroes; and even then informed local people knew of no instance in which a Negro got any of the money, their checks being endorsed over to white men in every known instance. The significance of this condition is too plain for argument when one realizes that Negroes constitute more than 70% of the dirt cotton farmers in Tuscaloosa County, and when one considers that the New Deal was intended to reach all the way down and benefit the man actually on the soil. It remains to be seen whether the Bankhead Act will give the 'croppers any better protection in 1934.

The Scottsboro Cases, the Angelo Herndon Case in Georgia, the impotence of the States to curb or punish lynching; the attempted murder of two Negro lawyers near Henderson, North Carolina, for daring to challenge the exclusion of Negroes from a North Carolina jury, reflect the load carried by the Negro in the courts of "justice"?

In the field of government you must know how the Federal Civil Service rules requiring candidates to state their race and submit their photograph with their application have been used to eliminate Negroes as a class from all appointments covered by civil service above the grades of laborer or messenger. An obstinate policy of the War and Navy Departments has decimated the ranks of Negro soldiers and sailors, and effectively emasculated those still left in the service of most of their self-respect; a matter which I predict the United States will seriously regret in the event of another war. You must know something of the humiliation and procrastination which Negro white collar workers met in many sections last winter when they applied for work under the CWA. The newspapers have been full of the DePriest resolution against racial discrimination in the House Restaurant in Washington, and the assault on a cultured Negro woman for the sole offense that she was hungry and tried to get service in the Senate restaurant during the hearings on the Costigan-Wagner Anti-Lynching Bill.

The plight of the Negro worker in agriculture, domestic service and industry; the disproportionate number of Negro families on relief due to job displacements and other loss of work, with attendant loss of self-assurance, are open sores calling for social surgery of the highest order. But there is no use piling up the deficit.

On the credit side we can point to certain advances. The Negro has made some progress under the New Deal; and at least in the Federal Government there is an increasing tendency to give him a voice in his own interest and to include his requirements in the national recovery. The Attorney General of Ohio has just overthrown the designation of race and use of photograph in the Ohio State Civil Service applications by declaring it an unconstitutional discrimination. The State of Maryland in 1933 made a bold attempt to bring the lynchers of George Armwood to justice. The Commonwealth of Virginia is reforming its jury system. Southern women are moving rapidly to the front in interracial work. And your own Association has exhibited significant liberal tendencies.