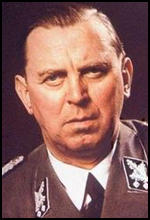

Julius Schaub

Julius Schaub was born in Munich, Germany, on 20th August, 1898. He joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). In April 1923 NSDAP headquarters received a letter accusing his wife of prostitution and procuring. The marriage was dissolved two years later.

According to Traudl Junge: "Both Schaub's feet had been injured in the First World War, leaving him crippled. Later he had joined the NSDAP; and Hitler noticed him as an ardent admirer who always attended Party meetings, hobbling in on his crutches wherever Hitler appeared. When Hitler discovered that Schaub had lost his job because of his Party membership he took him on as a valet."

In November, 1923, Schaub took part in the Munich Putsch. He was arrested and served time in Landsberg Castle. During this time he he became close to Adolf Hitler. On his release he worked for Hitler as his personal assistant. He joined the inner-circle that included Heinrich Hoffmann, Max Amann, Emil Maurice, Wilhelm Brückner and Hermann Kriebel. Schaub described himself as "Hitler's shadow, his daily companion, his constant retainer... perhaps the only person who could, outspokenly but with impunity, tell him anything that came into his head... In addition to the qualities required of a personal aide - notably, discretion, reliability and circumspection."

It has been argued by Lothar Machtan, the author of The Hidden Hitler (2001): "Julius Schaub... organized Hitler's private life from early 1925... He accompanied him on his travels, handled his finances and ran his household. He welcomed guests, got rid of unwelcome visitors and thus controlled access to Hitler. Of all the men in his immediate circle, it was Schaub who had the most detailed information about all of Hitler's intimate and personal affairs."

In 1931 Schaub married for a second time. Hitler was a witness and made his home available for the wedding reception. One of his weaknesses was drink. At parties he always "behaved atrociously" but when this was reported to Hitler he merely made "a despairing gesture" and sighed: "yes, I know, it's sad, but what can I do? He's the only aide I've got." Despite this, Schaub and Hitler always remained close.

Ian Kershaw has pointed out in Hitler 1889-1936 (1998) that after Adolf Hitler took power in 1933 his inner-circle became even more important: "Hitler had taken his long-standing Bavarian entourage into the Reich Chancellery with him. His adjutants and chauffeurs, Bruckner, Schaub, Schreck (successor to Emil Maurice, sacked in 1931 as chauffeur after his flirtation with Geli Raubal), and his court photographer Heinrich Hoffmann were omnipresent, often hindering contact, frequently interfering in a conversation with some form of distraction, invariably listening, later backing Hitler's own impressions and prejudices."

Christa Schroeder, was Hitler's personal secretary and had a lot of contact with Schaub. She wrote in her autobiography, He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary (1985): "He (Julius Schaub) had rather staring eyes, and because some of his toes had been frozen in the First World War, he sometimes walked with a hobbling gait. It may have been this disability that made him so cantankerous. Always suspicious, and full of curiosity into the bargain, and inclined to give a wide berth to everything that wasn't congenial to him, his popularity in Hitler's circle was limited."

Another secretary, Traudl Junge, commented: "His devotion, reliability and loyalty made him indispensable. He slowly worked his way up to adjutant and finally to chief adjutant, because he was the only one of the old guard who had been through the early years of the struggle himself, and he shared many experiences in common with Hitler. He knew so many of the Führer's personal secrets that Hitler just couldn't make up his mind to do without him."

At the end of 1943 the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) and the Gestapo managed to arrest several Germans involved in plotting to overthrow Hitler. This included Dietrich Bonhoffer, Klaus Bonhoffer, Josef Muller and Hans Dohnanyi. Others under suspicion like Wilhelm Canaris and Hans Oster were dismissed from office in January, 1944.

Major Claus von Stauffenberg now emerged as the leader of the group opposed to Nazi rule. He was joined by Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Ulrich Hassell, Hans Oster, Peter von Wartenburg, Henning von Tresckow, Friedrich Olbricht, Werner von Haeften, Wilhelm Canaris, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Ludwig Beck and Erwin von Witzleben. After the assassination of Hitler, Hermann Goering and Heinrich Himmler it was planned for troops in Berlin to seize key government buildings, telephone and signal centres and radio stations.

At least six attempts were aborted before Claus von Stauffenberg decided on trying again during a conference attended by Hitler on 20th July, 1944. It was decided to drop plans to kill Goering and Himmler at the same time. Stauffenberg, who had never met Hitler before, carried the bomb in a briefcase and placed it on the floor while he left to make a phone-call. The bomb exploded killing four men in the hut. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived the bomb blast. Hitler had a badge struck to honor all those injured or killed in the blast. Hitler's aides later said that Schaub, who was in a building some distance from the explosion, falsely tried to claim he was injured so as to be able to wear the badge.

Lothar Machtan, the author of The Hidden Hitler (2001), has pointed out that Schaub stayed with Hitler until he committed suicide: "The finest proof that he really could count on their loyalty was supplied at the end of April 1945, once again by Julius Schaub, who left the flaming ruins of Berlin at the last possible moment and set off for Bavaria, where he emptied the safes in Hitler's Munich apartment and on the Obersalzberg and burned their contents. What these documents were, Schaub doggedly refused to divulge until the day he died. All he once volunteered, in a mysterious tone of voice, was that their disclosure would have had 'disastrous repercussions.' Probably on himself, but most of all, beyond doubt, on Hitler."

Schaub, possessing false ID papers with the name "Josef Huber", was arrested on 8th May, 1945 in Kitzbuehl by American troops. The authorities could not find any evidence that he had participated in war crimes and he was released on 17th February, 1949.

Julius Schaub died in Munich on 27th December, 1967.

Primary Sources

(1) Ian Kershaw, Hitler 1889-1936 (1998)

Hitler had taken his long-standing Bavarian entourage into the Reich Chancellery with him. His adjutants and chauffeurs, Bruckner, Schaub, Schreck (successor to Emil Maurice, sacked in 1931 as chauffeur after his flirtation with Geli Raubal), and his court photographer Heinrich Hoffmann were omnipresent, often hindering contact, frequently interfering in a conversation with some form of distraction, invariably listening, later backing Hitler's own impressions and prejudices."

(2) Lothar Machtan, The Hidden Hitler (2001)

The finest proof that he really could count on their loyalty was supplied at the end of April 1945, once again by Julius Schaub, who left the flaming ruins of Berlin at the last possible moment and set off for Bavaria, where he emptied the safes in Hitler's Munich apartment and on the Obersalzberg and burned their contents. What these documents were, Schaub doggedly refused to divulge until the day he died. All he once volunteered, in a mysterious tone of voice, was that their disclosure would have had 'disastrous repercussions.' Probably on himself, but most of all, beyond doubt, on Hitler."

(3) Christa Schroeder, He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary (1985)

He (Julius Schaub) had rather staring eyes, and because some of his toes had been frozen in the First World War, he sometimes walked with a hobbling gait. It may have been this disability that made him so cantankerous. Always suspicious, and full of curiosity into the bargain, and inclined to give a wide berth to everything that wasn't congenial to him, his popularity in Hitler's circle was limited.

(4) Traudl Junge, To The Last Hour: Hitler's Last Secretary (2002)

The only fixture in the Führer bunker, besides his valets, was Hitler's chief adjutant, Gruppenfuhrer Julius Schaub. For historical research purposes it's not worth saying much about him, but even now I'm often asked how a statesman could keep such a strange character always with him and raise him to such a position of trust. So I must try to explain, even though I never really understood it myself.

Dear old Julius thought he was an amazingly important, significant person... I didn't yet know him at all when I heard the following little anecdote about him, and I can't be a hundred per cent certain that it's really true, but it's so typical that I just have to tell it. Even back in the mists of time, Schaub had been a Party member. His Party number was a very low one. Someone once asked him who really decided on the policies of the National Socialist Workers' party. Julius Schaub happened to be cleaning Hitler's boots at the time, and was acting as his valet. He replied: "Oh, that's me - and Hitler", and after a moment's hesitation he added, "And Weber too!"

Both Schaub's feet had been injured in the First World War, leaving him crippled. Later he had joined the NSDAP; and Hitler noticed him as an ardent admirer who always attended Party meetings, hobbling in on his crutches wherever Hitler appeared. When Hitler discovered that Schaub had lost his job because of his Party membership he took him on as a valet. Soon his devotion, reliability and loyalty made him indispensable. He slowly worked his way up to adjutant and finally to chief adjutant, because he was the only one of the old guard who had been through the early years of the struggle himself, and he shared many experiences in common with Hitler. He knew so many of the Führer's personal secrets that Hitler just couldn't make up his mind to do without him.

In a way we secretaries regarded Herr Schaub as our boss too. We had to deal with his post, copy out the petitions sent to him that he wanted to put before Hitler - most of them were from people the Führer knew - and deal with the mail coming into and going out of the personal adjutant's office.

Obviously we could hardly write letters exactly as he dictated them to us. Most of them had to be translated from Bavarian dialect into German first. On the whole Julius Schaub was extremely kind, but very curious too. He was always collecting anecdotes so that he could entertain the Führer at breakfast. He passed on every joke told at the camp barber's to his master, usually missing the punch line.

He had long ago given up smoking for the Führer's sake, leaving drink as his only indulgence. He had an astonishing head for alcohol. The light would be on in his room until late at night, or you would hear his voice in the mess, or from another bunker where some of the gentlemen were sitting around a bottle in earnest conversation. The amazing thing was, however, that he would go to the barber's freshly washed at eight in the morning, then walk round to the camp to show everyone that he was an early riser and a lesson to anyone who slept late. Only much later did I realize that after his morning walk, when the whole camp had respectfully noticed that Herr Schaub was up and about already, he went back to bed and slept happily until noon.