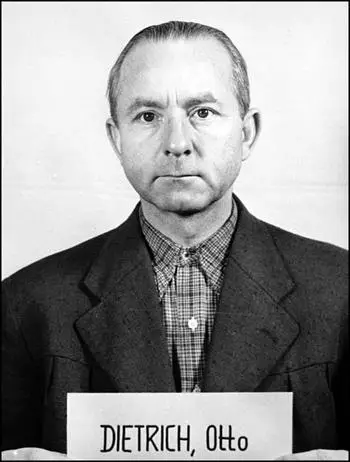

Otto Dietrich

Otto Dietrich was born in Essen on 31st August, 1897. During the First World War he served in the German Army and was awarded the Iron Cross (First Class). After the war he studied at Freiburg University, Munich University and Goethe University. In 1921 he graduated with a doctorate in political science and worked as a journalist in Munich.

In 1928 he became business manager of the Augsburger Zeitung. The following year he joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). He became a friend of Emil Kirdorf, and worked as an intermediary between Adolf Hitler and Rhineland industrialists.

As Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) has pointed out: "Kirdorf was one of the biggest names in German in dustry, the chief shareholder of the Gelsenkirchen Mine Company, the founder of the Ruhr Coal Syndicate, and the man who controlled the political funds of the Mining Union and the North-west Iron Association, the so-called Ruhr Treasury (Ruhrschatz). Kirdorf was a guest of honour and was so impressed by the 60,000 National Socialists who assembled to cheer their leader that he wrote afterwards to Hitler: "My wife and I shall never forget how overwhelmed we were in attending the memorial celebration for the World War dead."

In August, 1931, Dietrich was appointed Press Chief of the NSDAP. Dietrich later wrote: "In the summer of 1931 our Führer suddenly decided to concentrate systematically on cultivating the influential economic magnates... In the following months he traversed Germany from end to end, holding private interviews with prominent personalities. Any rendezvous was chosen, either in Berlin or in the provinces, in the Hotel Kaiserhof or in some lonely forest-glade. Privacy was absolutely imperative, the Press must have no chance of doing mischief. Success was the consequence."

On 30th June, 1934, Dietrich accompanied Hitler and the Schutzstaffel (SS), arrived at Bad Wiesse, where he personally arrested Ernst Roehm. During the next 24 hours 200 other senior SA officers were arrested on the way to the meeting. Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, witnessed what happened: "Hitler entered Roehm's bedroom alone with a whip in his hand. Behind him were two detectives with pistols at the ready. He spat out the words; Roehm, you are under arrest. Roehm's doctor comes out of a room and to our surprise he has his wife with him. I hear Lutze putting in a good word for him with Hitler. Then Hitler walks up to him, greets him, shakes hand with his wife and asks them to leave the hotel, it isn't a pleasant place for them to stay in, that day. Now the bus arrives. Quickly, the SA leaders are collected from the laundry room and walk past Roehm under police guard. Roehm looks up from his coffee sadly and waves to them in a melancholy way. At last Roehm too is led from the hotel. He walks past Hitler with his head bowed, completely apathetic."

Hitler later claimed that 61 members of the Sturmabteilung (SA) had been executed while 13 had been shot resisting arrest and three had committed suicide. According to Louis L. Snyder: "the next day he gave a blood-curdling account of the slaughter to the press. He described Hitler's sense of shock at the moral degeneracy of his oldest comrades."

According to Albert Speer, the author of Inside the Third Reich (1970), during this period, Hitler's inner-circle included Otto Dietrich, Joseph Goebbels, Herman Goering, Hermann Esser, Wilhelm Brückner, Julius Schreck, Sepp Diettrich, Julius Schaub, Heinrich Hoffmann, Franz Schwarz and Max Amann: "Evenings he usually had some trusty companions about: Schreck, his chauffeur for many years; Sepp Dietrich, the commander of his SS bodyguard; Dr. Otto Dietrich, the press chief; Brückner and Schaub, his two adjutants; and Heinrich Hoffmann, his official photographer. Since the table held no more than ten persons, this group almost completely filled it. For the midday meal, on the other hand, Hitler's old Munich comrades foregathered, such as Amann, Schwarz and Esser... I saw very little of Himmler, Roehm or Streicher at these meals, but Goebbels and Goering were often there."

In 1938 Dietrich was promoted to Press Chief of the Reich and State Secretary to the Propaganda Ministry. His main task was to present the Nazi world view to the German public. According to Dietrich, "the individual has neither the right nor the duty to exist." His job became more important after the outbreak of the Second World War. Dietrich had the responsibility of issuing a daily directive for newspapers on how to present the news from the front.

There was a crisis when Rudolf Hess flew to Scotland on 10th May, 1941. At first he reported that Hess was a victim of an accident over enemy territory. The Propaganda Minister, Dr. Joseph Goebbels, protested at this approach as he felt that the world should be told that Hess was a traitor. Dietrich now issued a new statement: "He (Hess) was motivated by pacifism. He was not a traitor, because there was nothing to betray."

Dietrich produced very positive reports on Operation Barbarossa. On 8th October, 1941, he argued that the Red Army was locked in two German steel traps: "For all military purposes, Soviet Russia is finished. The British dream of a two front war is dead." In January 1943, when the forces led by General Friedrich von Paulus were about to surrender, Dietrich had a nervous breakdown.

Dietrich was arrested by allied forces in 1945. He was tried for crimes against humanity and being a member of a criminal organization, at Nuremberg. On 11th April, 1949, was sentenced to seven years' imprisonment. He was released in 1950. During his time in Landsberg Prison he wrote The Hitler I Knew. Memoirs of the Third Reich's Press Chief. It was first account from a leading figure in the Nazi Party that expressed remorse about what had happened.

Otto Dietrich died in Düsseldorf on 22nd November 1952.

Primary Sources

(1) Otto Dietrich, With Hitler on the Road to Power (1934)

In the summer of 1931 our Führer suddenly decided to concentrate systematically on cultivating the influential economic magnates... In the following months he traversed Germany from end to end, holding private interviews with prominent personalities. Any rendezvous was chosen, either in Berlin or in the provinces, in the Hotel Kaiserhof or in some lonely forest-glade. Privacy was absolutely imperative, the Press must have no chance of doing mischief. Success was the consequence.

(2) Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (1970)

Evenings he usually had some trusty companions about: Schreck, his chauffeur for many years; Sepp Dietrich, the commander of his SS bodyguard; Dr. Otto Dietrich, the press chief; Brückner and Schaub, his two adjutants; and Heinrich Hoffmann, his official photographer. Since the table held no more than ten persons, this group almost completely filled it. For the midday meal, on the other hand, Hitler's old Munich comrades foregathered, such as Amann, Schwarz and Esser... I saw very little of Himmler, Roehm or Streicher at these meals, but Goebbels and Goering were often there.