Women Police Volunteers (WPV)

In 1914 the Headmistresses' Association suggested the formation of a female police force to control the behaviour of young women. As a result, over 2,000 Women's Patrols were formed and every night would tour public parks and visit cinemas in an attempt to prevent acts of immorality.

Margaret Damer Dawson, Secretary of the International Congress of Animal Protection Societies, was another who was concerned about the behaviour of young women. With the support of Sir Edward Henry, the Chief Commissioner of Police, she formed the Women Police Volunteers (WPV) with Nina Boyle. The government had always opposed the idea of policewomen but with the outbreak of the First World War and large numbers of policemen joining the British Army, it was considered a good idea to have women volunteers to help run the service. Another reason that Dawson's proposal was accepted was that her members were willing to work without pay.

In 1915 Margaret Damer Dawsonbecame Commandant and Mary Allen became Sub-Commandant. Allen, a member of the Women Political and Social Union who had been imprisoned three times during the campaign for the vote. She later remarked in her book, The Pioneer Policewoman, that: "A sense of humour had kept me from any bitterness. I was quite as enthusiastically ready to work with and for the police as I had been prepared, if necessary, to enter into combat with them."

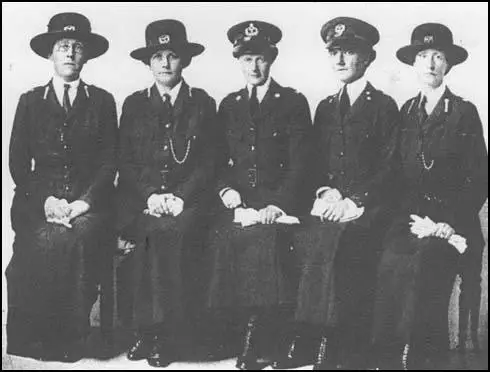

In 1915 Dawson renamed her organisation, the Women's Police Service (WPS). At first the organization concentrated its work in the London area. Wearing a dark-blue uniform, the WPS were assigned responsibilities such as looking after the welfare of refugees.

Grantham in Lincolnshire became the first provincial town to form a branch of the Women's Police Service. Impressed by the achievements of the WPS in Grantham, two of the women were made full members of the police force. In a meeting held in November, 1915, the Bishop of Grantham praised the work of the WPS and called for a national Women's Police Force.

In 1916 the Admiralty recruited a member of the WPS as an undercover worker in an attempt to expose spying and drug taking at the Scapa Flow Naval Base. The Ministry of Munitions also used the WPS to search women workers at its factories. At Gretna, near Carlisle, over 9,000 women were employed to produce munitions and 150 members of the WPS had the responsibility of searching them when they entered and left the factory.

By 1918 WPS women were on duty in Edinburgh, Birmingham, Glasgow, Bristol, Belfast, Oxford, Cambridge, Grantham, Portsmouth, Folkestone, Hull, Plymouth, Brighton, Reading, Nottingham, London and Southampton. However, in many cases they were not sworn in as full members of the local police force and could not make arrests.

When the Armistice was signed, there were over 357 members of the Women's Police Service. Commandant Margaret Damar Dawson and Subcommandant Mary Allen, asked the Chief Commissioner, Sir Nevil Macready, to make them a permanent part of his force. He refused, saying that the women were "too educated" and would "irritate" male members of the force. Macready instead decided to recruit and train his own women.

The WPS continued as a voluntary service but in February, 1920, five members, including Mary Allen, were charged with wearing uniforms too similar to that of the one worn by the Metropolitan Women Police Patrols. After a four-day hearing Macready won his case and the WPS were forced to change its uniform and its name. After 1920 the Women's Police Service became the Women's Auxiliary Service.

Primary Sources

(1) In her autobiography, The Pioneer Policewoman, Mary Allen recalled the actions of one policewoman in a London tube station during the war.

A soldier (who had just returned from the Western Front) was so disordered while he was going down the stairs into the tube station, he became suddenly aware of the crowds of people coming up, he looked haggardly about, and evidently mistaking the hollow space below for the trenches and the ascending crowd for Germans, fixed his bayonet and charged. But for the women constable on duty at the turn of the staircase, who was quick enough to divine his trouble and hang on to him with all her strength to prevent his forward advance, he would have wounded many and caused danger and panic.

(2) Mrs. Creighton, Voluntary Patrol Committee, Annual General Meeting (1917)

The policewoman of the future will be taken from that class of women who are forced to earn their living by it, and not so much from the educated women who now take smaller or no pay for the sake of helping.

(3) Eveline W. Brainerd, The Outlook (10th September, 1924)

The proposal of the New York Women's Police Bureau to train college women for policework, though a new idea here, has had ten years' trial in England and has proved its worth. The head of the Women's Auxiliary Service for training women candidates for police service in Great Britain, Mary E. Allen, came to this country last spring to study our police systems and to speak on the business of the women constables as worked out in Great Britain.

No one in London would turn to gaze after the trim uniform of the Commandant, but here the visored cap, the high-collared shirtwaist and black tie, the trousers and full-skirted coat meeting the tops of the black boots, catch every eye. When the Commandant is caught with her cap off there is another surprise, for the heavy hair is close cropped -- not bobbed, notice. It frames a strong, kindly face, of a type seen more often in England than among the descendants of the settlers on this side of the river. One would not choose to have the steady eyes rest upon one at an untoward moment, but at the corners are humorous wrinkles that show she has never become obsessed by the sordid and tragic scenes known to the police.

The war conditions brought to sudden action in 1914 the plans for an experiment in women on the police force that had long been considered by a group of thoughtful Englishwomen whose social work had shown them the need for some more understanding and careful treatment of women and children than the police force as constituted could give. In that time of need their offer, as a private organization, to train women for appointment to the regular police force was readily accepted. Commandant Allen was one of these women. She herself served on the police force at Grantham, where the experiment was first tried out, and, having learned the job, working side by side with the "Bobbies," she became head of the training school for these new officers, who during the war numbered a thousand, and who are now to be found on the local staffs in various parts of England and Scotland, and in the occupied territory in Germany.