Women's Patrols

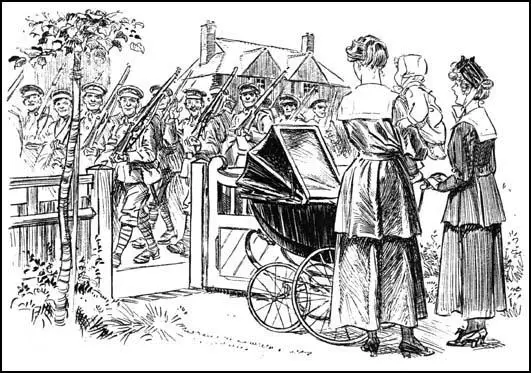

In the First World War it was decided to billet the soldiers in local towns and villages. Some people became concerned about the soldiers corrupting local girls. The Headmistresses' Association and the Federation of University Women suggested the formation of Woman's Patrols to stop local woman from becoming too friendly with the soldiers.

The War Office gave permission for these patrols to take place outside military camps. They were also very active in public parks and cinemas. After visiting 300 cinemas in three weeks, the Women's Patrol Committee recommended that lights were not dimmed between films.

Women's Patrols worked closely with the local police and the Women Police Volunteers. It is estimated that during the First World War over 2,000 patrols were established, including over 400 in London.

Mistress: "Which of them is your cousin?"

Nursemaid: (unguardedly): "I don't know yet, Ma'am.

Primary Sources

(1) Letter in The East Grinstead Observer from Charles Jenks of 34 Cantelupe Road (6th November, 1915)

I am writing to inform the council of the serious annoyance caused by inhabitants and visitors who use the public seats in the Mount Noddy Recreation Ground by the contemptible tactics of the Woman's Patrol. Having heard from various friends as well as from soldiers billeted at my house, of these women's actions, I went to the Mount Noddy Recreation Ground on Saturday evening from 9.30 pm to 10 pm. I saw two women make repeated journeys round the ground flashing electric torches on every seat as they passed. They also sat down on a seat adjacent to a couple who, as far as I could see were behaving in a perfectly correct manner. When this couple walked away the patrols directed a ray of light from a pocket torch on them, possibly with a view of finding out who they were. The council need to take steps to protect inhabitants and the exceedingly well-behaved troops quartered in the town from having this unjust slur cast upon their supposed behaviour.

(2) Letter signed 'One of the Annoyed' that appeared in The East Grinstead Observer (13th November, 1915)

Something must be done to stop these so- called "Ladies" from interfering with respectable girls and their friends. I'm not ashamed to admit that I made friends with several soldiers and I have found them to be perfect gentlemen. On two or three occasions one or two of these ladies spoke to me about the behaviour of the girls and soldiers in the town. These women seem to know all the girls in East Grinstead and Forest Row and all their business. They mentioned several things that I had done. They seem to know the exact place and time so I suppose they were watching me. I trust they will soon find something more useful to occupy their time.

(3) Unsigned letter in The East Grinstead Observer (13th November 1915)

It is about time something was done about ancient spinsters following soldiers about with their flash lights. I have seen a great deal of the soldiers who have been here and I consider that they have have been unfairly treated. Walking in the roads and fields accompanied by friends is no crime. What would these spinsters think if soldiers flashed a light upon them in their gardens or darkened drawing rooms?

(4) Letter in The East Grinstead Observer from M. Conner, 7 St. John's Road (20th November 1915)

I am not a member of a woman's patrol but I know several of these women and I admire their spirit and sacrifice. These women have an earnest desire for the welfare and morality of the girls. Preventative work is better than rescue work.

(5) Report by Women's Patrol during the war.

At a public house we watched three girls get into conversation with a sailor. Soon we beckoned to another and all five walked away. We followed until the girls, seeing us behind, turned sharply and left the men.

(6) Interview with a member of a Women's Patrol.

A special duty from the very first was to turn girls and lads out of the deep doorways and shop entrances. This is a job the police constable did not care to do, owing to the amount of abuse he got. But we never have any difficulty. Indeed the rule now is that as soon as we appear, out they come of their own accord, some sheepishly touching their caps with the remark: "All right, Miss." And yet we have not said a word.

(7) Helena Swanwick worked for the Women's International League during the First World War.

Sex before marriage was the natural female complement to the male frenzy of killing. If millions of men were to be killed in early manhood, or even boyhood, it behoved every young woman to secure a mate and replenish the population while there was yet time.

(8) Stephen McKenna, While I Remember (1921)

Anyone who lived in London during those feverish months had forced upon his notice a spectacle of debauchery which would have swelled the record of scandal if it had been made public but which is mercifully forgotten because it is incredible.