History of Women's Football

Scotland seems to be the first country in the world to encourage women to play football. In the 18th century football was linked to local marriage customs in the Highlands. Single women would play football games against married women. Single men would watch these games and use the evidence of their footballing ability to help them select prospective brides.

There is no evidence that women played football in England during the 18th century. In fact, until the formation of the Football League in 1885, football was dominated by the public schools. These early clubs feared that opposing sets of supporters would get into fights. As Dave Russell points out in Football and the English: A Social History of Association Football in England (1997): "in terms of social class, crowds at Football League matches were predominantly drawn from the skilled working and lower-middle classes... Social groups below that level were largely excluded by the admission price." Russell adds "the Football League, quite possibly in a deliberate attempt to limit the access of poorer (and this supposedly "rowdier") supporters, raised the minimum adult male admission price to 6d".

Several clubs came to the conclusion that male behaviour at football matches would be improved if they were accompanied by women. In April, 1885, Preston North End announced that women would be allowed free entry to all home games. Over 2,000 women turned up for the first game. Free entry for women was so popular that by the late 1890s all the football clubs had discontinued the scheme.

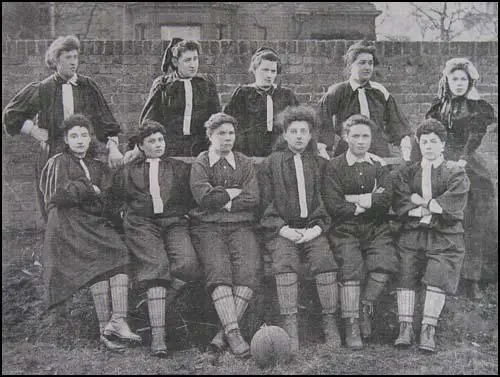

Nettie Honeyball helped to pioneer women's football in England. In 1894 Honeyball placed an advert in the press and persuaded about 30 young women to join the British Ladies Football Club. Honeyball persuaded J. W. Julian, who played for Tottenham Hotspur, to coach the women. The training sessions took place twice a week at a park next to the Alexandra Park racecourse at Hornsey.

Florence Dixie, the youngest daughter of the Marquis of Queensbury and another committed feminist, agreed to become president of the British Ladies Football Club on condition that "the girls should enter into the spirit of the game with heart and soul."

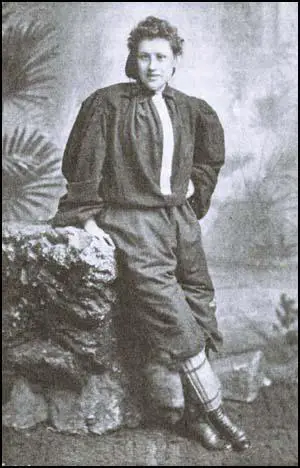

A decision had to be made about what the women would wear in games. One newspaper reporter explained: "The orthodox jerseys were made the basis of the attire, but it was seen that a great deal had been left to the coquetry and taste of the wearers. In many instances they were made loose after the manner of blouses and were relieved at the edges by a little white embroidering. Some of the sleeves, too, were made extremely wide, being evidently made after a decidedly fashion-plate pattern. There was the same variety in the make of the knickers. This would seem to be a personal matter for the ladies themselves. Several of them probably more advanced in reformed dress ideas than their sisters, wore the lower garments in the ordinary football fashion."

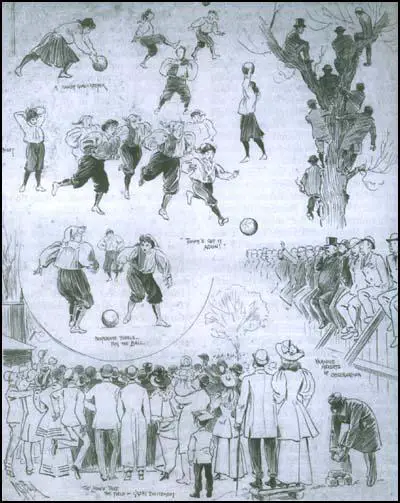

The first official match played by women took place at Crouch End in London on 23rd March, 1895. The girls were organized into teams that represented North and South London. The Manchester Guardian reported: "Their costumes came in for a good deal of attention.... one or two added short skirts over their knicker-bockers.... When the novelty has worn off, I do not think women's football will attract the crowds."

The Daily Sketch reporter claimed: "The first few minutes were sufficient to show that football by women, if the British Ladies be taken as a criterion, is totally out of the question. A footballer requires speed, judgement, skill, and pluck. Not one of these four qualities was apparent on Saturday. For the most part, the ladies wandered aimlessly over the field at an ungraceful jog-trot." North London (red), beat South London (light and dark-blue) 7-1.

The Sportsman newspaper was much more supportive: "True, young men would run harder and kick more strongly, but, beyond this, I cannot believe that they would show any greater knowledge of the game or skill in its execution. I don't think the lady footballer is to be snuffed out by a number of leading articles written by old men out of sympathy both with football as a a game and the aspirations of the young new women. If the lady footballer dies, she will die hard."

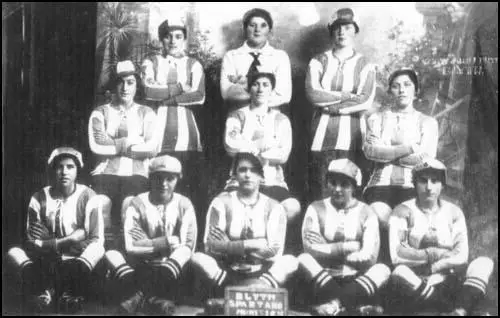

is second from the left in the top row.

The game was condemned by the male establishment. The British Medical Journal published an article condemning who played football: "We can in no way sanction the reckless exposure to violence, of organs which the common experience of women had led them in every way to protect."

On 6th April 1895 the British Ladies Football Club played at Preston Park in Brighton. The event was organised to raise funds for local medical charities. This time the North beat the South 8-3.

The next game was played in Bury. Over 5,000 people turned up to see the game and around £100 was raised for charity. This time the score was 3-3. Like in the other two games, Daisy Allen, the North's left-winger, was the outstanding player on view. The Bury Times described her as "a little sprite of four feet". According to one newspaper report, Daisy Allen was only 11 years old.

On Easter Monday 1895, Honeyball took the British Ladies Football Club to play on the ground used by Reading in the Southern League. The Berkshire Chronicle reported that a record crowd watched the game, beating the previous best, a league game between Reading and Luton Town. Rosa Thiere of the North team scored the only goal of the game.

The following day the club played at Ashton Gate in Bristol. This time the South beat the North 5-2. The Bristol Times was only impressed with the performance of one player. Daisey Allen was described as a "plucky youngster... who charged her bigger companions with great courage, and showed by her play that she had mastered the rudiments of the game, which could not be said for all."

Florence Dixie arranged for the British Ladies Football Club to play some games in Scotland. The local newspaper poked fun at the women. One journalist commented: "One of the full-backs was suspected of playing in her brother's knickers. The fair player was frequently asked for the name of her tailor."

After playing in New Brompton and Walsall, the British Ladies Football Club visited Newcastle where they played at the famous St. James's Park. Over 8,000 people saw the North win 4-3. Other games took place in South Shields and Darlington before playing at Jesmond. This time only 400 people turned up to watch and local newspapers reported that the novelty of watching women players appeared to be wearing off. Honeyball's group returned home to London and the first attempt to popularize women's football had come to an end.

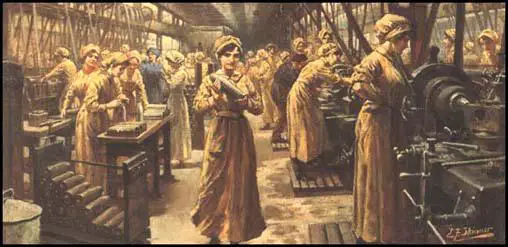

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. The role of women changed dramatically during the First World War. As men left jobs to fight overseas, they were replaced by women.

Women filled many jobs brought into existence by wartime needs. As a result the number of women employed increased from 3,224,600 in July, 1914 to 4,814,600 in January 1918. Nearly 200,000 women were employed in government departments. Half a million became clerical workers in private offices. Women worked as conductors on trams and buses. A quarter of a million worked on the land. The greatest increase of women workers was in engineering. Over 700,000 of these women worked in the highly dangerous munitions industry.

The women working in factories began to play football during lunch-breaks. Teams were formed and on Christmas Day in 1916, a game took place between Ulverston Munitions Girls and another group of local women. The munitionettes won 11-5. Soon afterwards, a game between munitions factories in Swansea and Newport. The Hackney Marshes National Projectile Factory formed a football team and played against other factories in London.

David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, encouraged these games as it helped reinforce the image of women doing the jobs normally done by men now needed to fight on the Western Front. This was especially important after the introduction of conscription in 1916. These matches also helped to raise money for wartime charities.

Alfred Frankland worked in the offices of the Dick, Kerr factory in Preston. During the First World War the company produced locomotives, cable drums, pontoon bridges, cartridge boxes and munitions. By 1917 it was producing 30,000 shells per week. Frankland used to watch the young women workers from his office window, kicking the ball around in their dinner-breaks. Alice Norris, one of the young women who worked at the factory later recalled these games: "We used to play at shooting at the cloakroom windows. they were little square windows and if the boys beat us at putting a window through we had to buy them a packet of Woodbines, but if we beat them they had to buy us a bar of Five Boys chocolate."

Grace Sibbert eventually emerged as the leader of the women who enjoyed playing football during the dinner-breaks. Born on 13th October, 1891, Grace's husband took part in the Battle of the Somme and in 1916 had been captured by the German Army and was at the time in a POW camp. Alfred Frankland suggested to Grace Sibbert that the women should form a team and play charity matches. Sibbert liked the idea and Frankland agreed to became the manager of the team.

Frankland arranged for the women to play a game on Christmas Day 1917, in aid of the local hospital for wounded soldiers at Moor Park. Frankland persuaded Preston North End to allow the women to play the game at their ground at Deepdale. It was the first football game to be played on the ground since the Football League programme was cancelled after the outbreak of the First World War. Over 10,000 people turned up to watch the game. After paying out the considerable costs of putting on the game, Frankland was able to donate £200 to the hospital (£41,000 in today's money).

Dick Kerr's beat the Arundel Courthard Foundry, 4-0. They went onto play and defeat other factories based in Barrow-in-Furness and Bolton. The stars of the team included the captain, Alice Kell, the centre-forward, Florrie Redford, and the hard-tackling defender, Lily Jones.

On 21st December, 1918, the team played against Lancaster Ladies at Deepdale and lost the game 1-0. Alfred Frankland was impressed with the performances of three of the women playing for Lancaster: Jennie Harris, Jessie Walmsley and Anne Hastie. Four days later, the three women had been persuaded to join the Preston side and played against Bolton Ladies on Christmas Day, 1918. Soon afterwards, another Lancaster player, Molly Walker, joined the side. Frankland also recruited players from Bolton (Florrie Haslam) and Liverpool (Daisy Clayton).

At the end of the First World War most women lost their jobs in the munitions factories. However, some retained their interest in football. For example, the Sutton Glass Works women's football team reformed as St Helens Ladies' AFC. Some teams retained the support of their employers. This included the Dick, Kerr factory in Preston.

At first men found it difficult to accept that women should play football. David J. Williamson argued in Belles of the Ball (1991): "Nor surprisingly, it was extremely difficult for many men to accept the idea of ladies playing what had always been regarded as a male preserve, their sport. Those who had been away at the front during the Great War would have had no real idea as to how the country was changing in their absence; how the role of their womenfolk within society was beginning to change quite dramatically, responding to the opportunity they had been given."

In early 1919 Dick Kerr Ladies beat St. Helens Ladies 6-1. Alfred Frankland was very impressed with the performances of Alice Woods and her fourteen year-old team-mate, Lily Parr. After the game Frankland asked the two women to join his team. Records show that Frankland paid these women 10 shillings a game. In today's money that amounted to about £100. He also paid their travelling expenses.

Women's football games were extremely popular. For example, a game between Dick Kerr Ladies and Newcastle United Ladies played at St. James's Park, in September, 1919, attracted a crowd of 35,000 people and raised £1,200 (£250,000) for local war charities.

Games were usually preceded by a laying of wreaths on the graves of local football players killed during the First World War. For example, when they played in Blackburn, they placed a wreath in remberance of Edwin Latheron, the English international inside forward who had been killed at Passchendaele.

Lily Parr was one of the main stars of the team and in her first season scored 43 goals for the club. Gail J. Newsham wrote about Parr in her book, In a League of their Own (1994): "Standing almost six feet tall, with jet black hair, her power and skill was admired and feared, wherever she played. She was an extremely unselfish player who could pin-point a pass with amazing accuracy and was also a marvellous ball player. And she was probably responsible in one way or another, for most of the goals that were scored by the team".

In 1920 a local newspaper wrote about this talented 14 year old: "There is probably no greater football prodigy in the whole country. Not only has she speed and excellent ball control, but her admirable physique enables her to brush off challenges from defenders who tackle her. She amazes the crowd where ever she goes by the way she swings the ball clean across the goalmouth to the opposite wing."

One of her team-mates, Joan Whalley, remarked on Parr's sense of humour: "When the older players were getting ready for a match, there were elastic stockings going on knee's and strapping up of ankles, there were bandages here there and everywhere. Then Parr walked in, and she stood looking around at them all and said, "well, I don't know about Dick Kerr Ladies football team, it looks like a bloody trip to Lourdes to me!"

The women came under a great deal of pressure from their families not to play football. Molly Walker was treated as an outcast by her boyfriend's family because they did not approve of her wearing shorts and showing her legs.

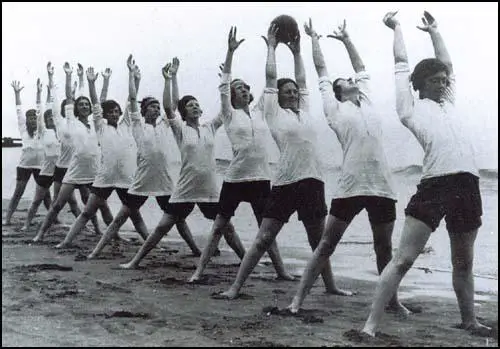

Dick Kerr Ladies trained at Ashton Park, a sports ground owned by the company. Several members of the Preston North End team helped with the coaching. This included Bob Holmes, Johnny Morley, Billy Grier and Jack Warner.

The managing director of the Dick, Kerr Company was John Kerr. He was also the Conservative Party MP for Preston. In 1919 the company was purchased by English Electric.

In 1920 Alfred Frankland arranged for the Federation des Societies Feminine Sportives de France to send a team to tour England. Madame Milliat, who had founded the federation, was a great advocate of women playing football: "In my opinion, football is not wrong for women. Most of these girls are beautiful Grecian dancers. I do not think it is unwomanly to play football as they do not play like men, they play fast, but not vigorous football."

Frankland believed that his team was good enough to represent England against a French national team. Four matches were arranged to be played at Preston, Stockport, Manchester and London. The matches were played on behalf of the National Association of Discharged and Disabled Soldiers and Sailors.

A crowd of 25,000 people turned up to the home ground of Preston North End to see the first unofficial international between England and France. England won the game 2-0 with Florrie Redford and Jennie Harris scoring the goals.

The two teams travelled to Stockport by charabanc. This time England won 5-2. The third game was played at Hyde Road, Manchester. Over 12,000 spectators saw France obtain a 1-1 draw. Madame Milliat reported that the first three games had raised £2,766 for the ex-servicemens fund.

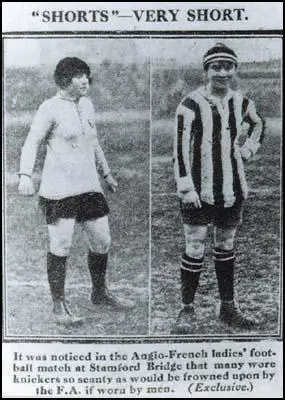

The final game took place at Stamford Bridge, the home of Chelsea Football Club. A crowd of 10,000 saw the French Ladies win 2-1. However, the English Ladies had the excuse of playing most of the game with only ten players as Jennie Harris suffered a bad injury soon after the game started. This game caused a stir in the media when the two captains, Alice Kell and Madeline Bracquemond, kissed each other at the end of the match.

On 28th October, 1920. Alfred Frankland took his team to tour France. On Sunday 31st October, 22,000 people watched the two sides draw 1-1 in Paris. However, the game ended five minutes early when a large section of the crowd invaded the pitch after disputing the decision by the French referee to award a corner-kick to the English side. After the game Alice Kell said the French ladies were much better playing on their home ground.

The next game was played in Roubaix. England won 2-0 in front of 16,000 spectators, a record attendance for the ground. Florrie Redford scored both the goals. England won the next game at Havre, 6-0. As with all the games, the visitors placed a wreath in memory of allied soldiers who had been killed during the First World War.

The final game was in Rouen. The English team won 2-0 in front of a crowd of 14,000. When the team arrived back in Preston on 9th November, 1920, they had travelled over 2,000 miles. As captain of the team, Alice Kell made a speech where she said: "If the matches with the French Ladies serve no other purpose, I feel that they will have done more to cement the good feeling between the two nations than anything which has occurred during the last 50 years."

Soon after arriving back in Preston, Alfred Frankland was informed that the local charity for Unemployed Ex Servicemen was in great need for money to buy food for former soldiers for Christmas. Frankland decided to arrange a game at between Dick Kerr Ladies and a team made up of the rest of England. Deepdale, the home of Preston North End was the venue. To maximize the crowd, it was decided to make it a night game. Permission was granted by the Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill, for two anti-aircraft searchlights, generation equipment and forty carbide flares, to be used to floodlight the game.

Over 12,000 people came to watch the match that took place on 16th December, 1920. It was also filmed by Pathe News. Bob Holmes, a member of the Preston team that won the first Football League title in 1888-89, had the responsibility of providing whitewashed balls at regular intervals. Although one of the searchlights went out briefly on two occasions, the players coped well with the conditions. Dick Kerr Ladies showed they were the best woman's team in England by winning 4-0. Jennie Harris scored twice in the first half and Florrie Redford and Minnie Lyons added further goals before the end of the game. A local newspaper described the ball control of Harris as "almost weird". He added "she controlled the ball like a veteran league forward, swerved, beat her opponents with the greatest of ease, and passed with judgment and discretion". As a result of this game, the Unemployed Ex Servicemens Distress Fund received over £600 to help the people of Preston. This was equivalent to £125,000 in today's money.

On 26th December, 1920, Dick Kerr Ladies played the second best women's team in England, St Helens Ladies, at Goodison Park, the home ground of Everton. The plan was to raise money for the Unemployed Ex Servicemens Distress Fund in Liverpool. Over 53,000 people watched the game with an estimated 14,000 disappointed fans locked outside. It was the largest crowd that had ever watched a woman's game in England.

Florrie Redford, Dick Kerr Ladies' star striker, missed her train to Liverpool and was unavailable for selection. In the first half, Jennie Harris gave Dick Kerr Ladies a 1-0 lead. However, the team was missing Redford and so the captain and right back, Alice Kell, decided to play centre forward. It was a shrewd move and Kell scored a second-half hat trick which enabled the Preston side to beat St Helens Ladies by 4-0.

The game at Goodison Park raised £3,115 (£623,000 in today's money). Two weeks later the Dick Kerr Ladies played a game at Old Trafford, the home of Manchester United, in order to raise money for ex-servicemen in Manchester. Over 35,000 people watched the game and £1,962 (£392,000) was raised for charity.

The French team arrived for another tour of England in May, 1921. Their star player was Carmen Pomies. She was an outstanding athlete and was a champion javelin thrower in France. Pomies could play in goal or in the outfield. She was so good that Alfred Frankland persuaded her to live in Preston and play for Dick Kerr Ladies. Her first game was against Coventry Ladies on 6th August, 1921.

In 1921 the Dick Kerr Ladies team was in such demand that Alfred Frankland had to refuse 120 invitations from all over Britain. The still played 67 games that year in front of 900,000 people. It has to be remembered that all the players had full-time jobs and the games had to be played on Saturday or weekday evenings. As Alice Norris pointed out: "It was sometimes hard work when we played a match during the week because we would have to work in the morning, travel to play the match, then travel home again and be up early for work the next day."

The players called Alfred Frankland "Father" or "Pop". Like many men of his generation he always "lifted his hat" when talking to women. He also wore a three piece suit and expected his players to be well dressed. As Nancy Thompson pointed out: "Mr. Frankland demanded nothing but the best for us, the absolute best. But he also expected the best from us in return. we weren't allowed to wear trousers anywhere in public, it wasn't done in those days. We could do what we liked on the bus when we were travelling, but we had to change back into our skirts or dresses in the bus before we met any of the officials, that was a must."

In 1921 Herbert Stanley began helping Alfred Frankland run the team. A trainee accountant with an oil company in Preston, he was given responsibility for keeping the books. Herbert Stanley eventually married Alice Woods.

On 14th February, 1921, 25,000 people watched Dick Kerr Ladies beat the Best of Britain, 9-1. Lily Parr (5), Florrie Redford (2) and Jennie Harris (2) got the goals. Representing their country, the Preston team beat the French national side 5-1 in front of 15,000 people at Longton. Parr scored all five goals.

The Dick Kerr Ladies did not only raise money for Unemployed Ex Servicemens Distress Fund. They also helped local workers who were in financial difficulty. The mining industry in particular suffered a major recession after the war. In 1920 the mine-owners notified their workers that miners' wages were to be reduced. Robert Smillie, the president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) called a strike in an effort to persuade the owners to change their minds. Under the terms of the Triple Industrial Alliance, the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) and the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) declared that they take industrial action in support of the miners. However, at the last moment, the leaders of the NUR and TGWU changed their minds, and although the miners went ahead with their strike they eventually had to give in and accept lower wages.

In March, 1921, the mine-owners announced a further 50% reduction in miner's wages. When the miners refused to accept this pay-cut, they were locked out from their jobs. On April 1 and, immediately on the heels of this provocation, the government put into force its Emergency Powers Act, drafting soldiers into the coalfield.

The government and the mine-owners attempted to starve the miners into submission. Several members of the Dick Kerr team came from mining areas like St. Helens and held strong opinions on this issue and games were played to raise money for the families of those men locked out of employment. As Barbara Jacobs pointed out in The Dick, Kerr's Ladies: "Women's football had come to be associated with charity, and had its own credibility. Now it was used as a tool to help the Labour Movement and the trade unions. It had, it could be said, become a politically dangerous sport, to those who felt the trade unions to be their enemies.... Women went out to support their menfolk, a Lancashire tradition, was causing ripples in a society which wanted women to revert to their prewar roles as set down by their masters, of keeping their place, that place being in the home and kitchen. Lancashire lasses were upsetting the social order. It wasn't acceptable."

The 1921 Miners Lock-Out caused considerable suffering in mining areas in Wales and Scotland. This was reflected by games played in Cardiff (18,000), Swansea (25,000) and Kilmarnock (15,000). Dick Kerr Ladies represented England beat Wales on two successive Saturdays. They also beat Scotland on 16th April, 1921.

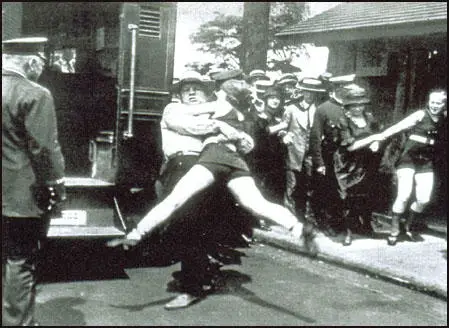

The Football Association was appalled by what they considered to be women's involvement in national politics. It now began a propaganda campaign against women's football. A new rule was introduced that stated no football club in the FA should allow their ground to be used for women's football unless it was prepared to handle all the cash transactions and do the full accounting. This was an attempt to smear Alfred Frankland with financial irregularities.

football included this postcard by Fred Spurgin.

Once again the issue was raised about the health risks of women's football. Dr Elizabeth Sloan Chesser said: "There are physical reasons why the game is harmful to women. It is a rough game at any time, but it is much more harmful to women than men. They may receive injuries from which they may never recover." Dr Mary Scharlieb, a Harley Street Physician added: "I consider it a most unsuitable game, too much for a woman's physical frame."

Barbara Jacobs argued in The Dick, Kerr's Ladies that "the FA brought out its tame doctors to verify that, in fact, football did terrible things to women's bodies. Mr Eustice Miles had a scientific reason for believing this, or so he said - "The kicking is too jerky a movement for women and the strain is likely to be severe." So are we to assume that women's bodies are unsuited to jerky movements? That's put paid to sex, hasn't it?"

Alfred Frankland invited Dr Mary Lowry to watch a game being played by Dick Kerr Ladies. Afterwards she commented: "From what I saw, football is no more likely to cause injuries to women than a heavy day's washing."

The captain of Huddersfield Atalanta argued: "If football were dangerous some ill-effect would have been seen by now. I know that all our girls are healthier and, speaking personally, I feel worlds better than I did a year ago. Housework isn't half the trouble it used to be, because there is always Saturday's game and the week night training to freshen me up."

The captain of Plymouth Ladies gave an interview where she argued: "The controlling body of the F.A. are a hundred years behind the times and their action is purely sex prejudice. Not one of our girls has felt any ill effects from participating in the game."

On 5th December 1921, the Football Association issued the following statement:

Complaints having been made as to football being played by women, the Council feel impelled to express their strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged.

Complaints have been made as to the conditions under which some of these matches have been arranged and played, and the appropriation of the receipts to other than Charitable objects.

The Council are further of the opinion that an excessive proportion of the receipts are absorbed in expenses and an inadequate percentage devoted to Charitable objects.

For these reasons the Council requests the clubs belonging to the Association refuse the use of their grounds for such matches.

This measure removed the ability of women to raise significant sums of money for charity as they were now barred from playing at all the major venues. The Football Association also announced that members were not allowed to referee or act as linesman at any women's football match.

The Dick Kerr Ladies team were shocked by this decision. Alice Kell, the captain, spoke for the other women when she said: "We play for the love of the game and we are determined to carry on. It is impossible for the working girls to afford to leave work to play matches all over the country and be the losers. I see no reason why we should not be recompensated for loss of time at work. No one ever receives more than 10 shillings per day."

Alice Norris pointed out that the women were determined to resist attempts to stop them playing football: "We just took it all in our stride but it was a terrible shock when the FA stopped us from playing on their grounds. We were all very upset but we ignored them when they said that football wasn't a suitable game for ladies to play."

As Gail J. Newsham argued In a League of their Own: "So, that was that, the axe had fallen, and despite all the ladies denials and assurances regarding finances, and their willingness to play under any conditions that the FA laid down, the decision was irreversible. The chauvinists, the medical 'experts' and the anti women's football lobby had won - their threatened male bastion was now safe."

The continued existence of women's football was under threat. As David J. Williamson pointed out in Belles of the Ball: "All the majority of lady footballers had ever wanted to do was to simply play football! Over the years since the First World War they had given so much and asked very little in return. To he accused of, in effect, dipping their fingers in the till, only left them disgusted. Now that they had been officially banned the ladies would need to do an awful lot of thinking. To merely carry on and play the game would he more a question of survival than enjoyment. To achieve this new goal the ladies would need the guts and determination they had shown thus far. All the enthusiasm for the game that had so endeared them to the thousands of spectators at the charity matches now had to he brought to bear on simply keeping the game itself alive, if that was at all possible."

Alfred Frankland responded to the action taken by the Football Association with the claim: "The team will continue to play, if the organisers of charity matches will provide grounds, even if we have to play on ploughed fields."

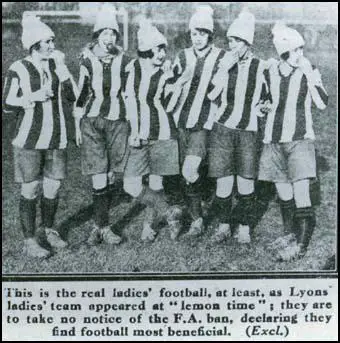

Some supporters of women's football welcomed the decision of the FA. "Football Girl" wrote a weekly column in the Football Special Magazine. She wrote: "Women's footballers have at last been roused to the necessity of organisation if they are to carry on, and the F.A. ban, having made us independent of outside bodies, has given us the additional impetus that will probably make us organise ourselves far more thoroughly than we should have done if we had been in a half-and-half situation, neither definitely sure of having F.A.'s assistance and yet to a large extent relying on it."

The first meeting of the English Ladies Football Association (ELFA) took place at Blackburn on 10th December 1921. At this time there were approximately 150 ladies' football clubs in England. The representatives of 25 clubs attended the initial meeting. This rose to 60 at the next meeting held in Grimsby.

The ELFA issued a statement that argued: "The Association is most concerned with the management of the game, and intend to insist that all clubs in the Association are run on a perfectly straightforward manner, so that there will be no exploiting of the teams in the interest of the man or firm who manages them."

The ELFA introduced its own set of rules and regulations. This included reducing the size of the pitch. It was also decided to use a lighter football, a change that was eventually adopted by the Football Association. Referees of women's matches were also given "greater powers concerning the use of ball skills rather than brawn".

ELFA also made a rule that any club that became affiliated to the ELFA would not be allowed to play against a team that was not a member. It was believed that the best way of making ELFA strong was to make it difficult for non-members to find matches.

ELFA also took measures to stop a club like Dick Kerr Ladies from developing again in the future. Alfred Frankland had obtained the best players by persuading them to play for his team. ELFA therefore decreed that no woman was to play for a club that was more than twenty miles from her home. The measure did a great deal to encourage clubs to develop local talent. This measure reduced the dominance of Dick Kerr Ladies who had recruited the best players available. This had resulted in them winning 99 out of their last 100 games. The only game they had failed to win was a draw against the French Ladies in Paris in October 1920.

On 7th January 1922, played Hey's Brewery Ladies from Bradford on Wakefield Trinity Rugby Football Club in aid of the Wakefield Workpeoples Hospital. The Bradford team was considered to be the best in Yorkshire. Frankland's team only managed to obtain a draw against Hey's Ladies with a disputed last minute penalty. Journalists claimed that the Bradford team had adapted better to the skills needed for the lighter ball. According to one writer new ball did not suit the "sturdy, some would say cumbersome skills of the girls" from Preston.

Women's football remained strong in the Midlands and the North but the ELFA found it difficult to recruit clubs in the South of England. In 1922, East Ham Ladies were forced to place adverts in local newspapers appealing for clubs to join the ELFA.

Alfred Frankland decided to take his team on a tour of Canada and the United States. The team included Jennie Harris, Daisy Clayton, Alice Kell, Florrie Redford, Florrie Haslam, Alice Woods, Jessie Walmsley, Lily Parr, Molly Walker, Carmen Pomies, Lily Lee, Alice Mills, Annie Crozier, May Graham, Lily Stanley and R. J. Garrier. Their regular goalkeeper, Peggy Mason, was unable to go due to the recent death of her mother.

When the Dick Kerr Ladies arrived in Quebec on 22nd December, 1922, they discovered that the Dominion Football Association had banned them from playing against Canadian teams. They were accepted in the United States, and even though they were sometimes forced to play against men, they lost only 3 out of 9 games. They visited Boston, Baltimore, St. Louis, Washington, Detroit, Chicago and Philadelphia during their tour of America.

Florrie Redford was the leading scorer on the tour but Lily Parr was considered the star player and American newspapers reported that she was the "most brilliant female player in the world". One member of the team, Alice Mills, met her future husband at one of the games, and would later return to marry him and become an American citizen.

In Philadelphia four members of the team, Jennie Harris, Florrie Haslam, Lily Parr, and Molly Walker, met the American Women's Olympic team in a relay race of about a quarter of a mile. Even though their fastest runner, Alice Woods, was unavailable through illness, the Preston ladies still won the race.

Dick Kerr Ladies continued to play charity games in England but denied access by the Football Association to the large venues, the money raised was disappointing when compared to the years immediately following the First World War. In 1923 the French Ladies came over for their annual tour of England. They played against Dick Kerr Ladies at Cardiff Arms Park. Part of the proceeds were for the Rheims Cathedral Fund in France.

Dick, Kerr Engineering was eventually taken over by English Electric. Although they allowed the team to play on Ashton Park, it refused to subsidize the football team. Alfred Frankland was also told that he would no longer be given time off to run the team that was now known as the Preston Ladies.

Frankland decided to leave English Electric and open a shop with his wife in Sharoe Green Lane in Preston where they sold fish and greengroceries. He continued to manage Preston Ladies with great success.

Some of the players also lost their jobs with English Electric. Over the years Frankland had raised considerable sums of money for Whittingham Hospital and Lunatic Asylum. The hospital was always willing to employ and provide accommodation for Frankland's players. This included Lily Parr, Florrie Redford, Jessie Walmsley, Lily Lee and Lily Martin. In 1923 Frankland persuaded Lizzy Ashcroft and Lydia Ackers, two of St Helens best players, to join Preston Ladies. Both women went to work for Whittingham Hospital.

Lydia Ackers later told Gail J. Newsham: "He (Frankland) got me my job at Whittingham, he was in with everybody. After the war there was no work at Dick Kerr's and when the team were finishing at the factory, they all went to work at the hospital."

Nancy Thompson played for Edinburgh Ladies before joining Preston Ladies: "Mr. Frankland had contacted me several times about playing for the team. He said a job would be found for me and also a place to live. He had a lot of influence at Whittingham Hospital and he got me a job there without any form to sign, no introduction, not even an interview."

During the General Strike English Electric stopped Preston Ladies from playing on Ashton Park. Alice Norris pointed out: "It was our training night and we were told not to go up to Ashton Park anymore. Something must have gone wrong between him (Frankland) and the firm."

Despite the lack of sponsorship, Preston Ladies continued to be the best team in England. In 1927 they beat their rivals for the title, Blackpool Ladies, 11-2. Florrie Redford, Jennie Harris and Lily Parr all scored goals in the game.

Alice Woods stopped playing for Preston Ladies when she married Herbert Stanley in September, 1928. Other players like Alice Kell got married and gave up football. Florrie Redford emigrated to Canada in 1930 to pursue her career as a nurse whereas Carmen Pomies returned to France. Jennie Harris kept playing until the mid-1930s.

Lily Parr, who never got married, continued to play football for Preston Ladies. Lydia Ackers, who played for many years with Parr argued that: "I have never seen any woman, nor many a man, kick a ball like she could. Everybody was amazed when they saw her power, you would never believe it."

Joan Whalley was another one who played in the same team as Lily Parr later wrote: "She had a kick like a mule. she was the only person I knew who could lift a dead ball, the old heavy leather ball, from the left wing over to me on the right and nearly knock me out with the force of the shot.... When she took a left corner kick, it came over like a bullet, and if you ever hit one of those with your head... I only ever did it once and the laces on the ball left their impression on my forehead and cut it open."

Some shrewd observers believed she was good enough to play for a club in the Football League. Bobby Walker, a Scottish international player, belied that she was the "best natural timer of a football I have ever seen." Alfred Frankland went further describing her as the "best outside left playing in the world today."

The action of the Football Association reduced the popularity of women's football in Britain. As Ali Melling has pointed out in Women and Football (2002): "The ban marked the start of a decline in the game, and during the 1920s and 1930s ladies' football was reduced to a minor sub-culture."

The Ladies Football Association ended in failure and women's football was unable to develop any formal structure. A declining number of women's teams arranged charity games throughout the season. There were never enough teams to enable the formation of any women's league.

On 8th September, 1937, Preston Ladies beat Edinburgh Ladies to win the "championship of Great Britain and the World". Preston won 5-1 with Lily Parr scoring one of the goals. Joan Whalley, who was only 15, also scored. A World Championship Victory Dinner was held at Booths Cafe in Preston.

Alfred Frankland made a speech where he claimed: "Since our inception we have played 437 matches, won 424, lost 7 and drawn 6, scored 2,863 goals and had only 207 scored against. We have raised over £100,000 in this country and in foreign lands for charity. We have won 14 silver cups, 5 of them outright, and hold a trophy awarded for the most meritorious assistance given to ex-servicemen."

Preston Ladies only played a small number of games during the Second World War. The rationing of petrol made it difficult to travel to games. Alfred Frankland also worked as a ARP Warden during the war and did not have the time to organize games.

In 1946 Lily Parr was made captain in recognition of 26 years service. She had only missed 5 games since joining the team in 1920. The local newspaper reported that she had scored 967 goals out of the teams total score of 3,022.

The Football Association refused to lift its ban on women players. In 1947 the Kent County Football Association suspended a referee because he was working as a manager/trainer with Kent Ladies Football Club. It justified its decision with the comment that "women's football brings the game into disrepute".

In 1950 Alfred Frankland calculated that since 1917 Preston Ladies had played 643 games. Of these, they had only lost 9 games. He also claimed that that the team had raised £140,000 for charity.

Alfred Frankland was forced to retire as manager of Preston Ladies in 1955 because of poor health. Kath Latham became the new manager. Stella Briggs, the team captain, became joint manager with Latham in 1956. Frankland died on 9th October, 1957.

In the 1950s Val Walsh was Preston Ladies best player. According to Kath Latham: "Matt Busby came to see one of our matches at Blackpool. He sat in the stands and said of Val Walsh that she was the best player he had ever seen in his life, and if she had been a man, he would have signed her up there and then to play for Manchester United."

The Football Association continued to try and suppress the playing of women's football. In 1962 they stopped a match from taking place at the British Legion ground at Newton between Preston Ladies and Oldham Ladies in aid of the Wigan Society for the Blind. Wigan Rovers rented the ground from the British Legion and the FA told them that they faced suspension if they allowed the game to go ahead.

Ali Melling has argued in Women and Football (2002): "After the release of the Kinsey Report in the 1950s the situation was complicated by the growth of public awareness regarding homosexuality. Women were sometimes jeered at during matches with the result that many women players became victims of homophobia from both inside and outside the game."

Kath Latham found it increasingly difficult to find enough teams to play against Preston Ladies. In 1963 they only had 16 games. The following year the number dropped to 12 games. Latham also had difficulties obtaining players. Only a few lived in Preston and others had to travel from Wigan, Chorley, Southport and Manchester. This resulted in the club stopping training sessions and the women only got together for games.

In 1965 Kath Latham was only able to arrange three fixtures. They were all against the same club, Handy Angles from the Midlands. The third game was played on 21st August. Preston Ladies won 4-0. The same result as their first game in 1917. A few weeks later, Latham sent out a letter to her players informing them that the club was to fold.

The WFA established a women's cup competition in 1971. In the first final Southampton beat Stewarton and Thistle 4-1.

For many years Dick Kerr Ladies represented England against foreign national sides. The first official women's international in Britain took place at Greenock in November 1972. England beat Scotland 3-2.

In 1983 the WFA affiliated to the Football Association. Although the FA Women's Committee was chaired by a man, all other key posts were held by women. Women were also appointed to coach the national teams of England (Hope Powell) and Scotland (Vera Pauw).

The English side reached the final of the first UEFA women's tournament in 1984 and in 1985 won the first "Mini World Cup" competition.

Women's football has continued to grow in popularity. In September 1991 the WFA established a national league with 24 clubs. The number of women's teams playing in Britain increased from around 500 in 1993 to about 4,500 in 2000. There are also over 6,500 women coaches in Britain. In 2002 the Football Association published figures to suggest that football has become the top sport for girls and women in Britain.

I am indebted to the research carried out by Barbara Jacobs (The Dick, Kerr's Ladies) and Gail Newsham (In a League of their Own) for the information in this article.

Primary Sources

(1) Manchester Guardian (26th March, 1895)

Their costumes, of course, came in for a good deal of attention, but, thanks to the illustrated papers and the recent developments of gymnastics and cycling the general public has become so familiar with `Rational' dress that it no longer creates anything like a sensation. The ladies of the North team wore red blouses with white yolks, and full black knickerbockers fastened below the knee, black stockings, red berretta caps, brown leather boots and leg-pads. The South wore blouses of light and dark blue in large squares, and blue caps, the rest of their dress being the same as that of the other team. A few wore white gloves, and some discarded caps altogether. One or two added a short skirt above the knickerbockers, but this rather distracted from the good appearance of the dress, as the skirts flapped about in the wind and rendered movement less graceful. When the novelty has worn off I do not think that ladies football matches. will attract crowds, but there seems no reason why the game should not be annexed by women for their own use as a new and healthful form of recreation. One other point made clear by Saturday's exhibition, that the 'Rational' costume - that is, tunic and knickerbockers - is the only dress in which women will take active exercise in the future. The women's football match has settled that.

(2) Jarrow Express (29th March, 1895)

The members of the British Ladies' Football Club have played their first match in public. We hope (severely, says The Standard) it will be their last. There will always be curiosity to see women do unwomanly things, and it is not surprising that the match was attended by a crowd numbering several thousands, very few of whom would like to have their own sisters or daughters exhibiting themselves on the football field. Some of these young persons appeared to possess only an elementary knowledge of the game and its laws, and, for the present at all events, the club is quite unlikely to attract spectators for the sake of the play. How long it will continue to attract them for reasons unconnected with sport is another matter, but it is significant that a considerable proportion of those present left the field at half-time. The laughter was easy, and the amusement was rather coarse; but these are waning delights, and we shall be surprised if a second display wins even so equivocal a success as the first.

(3) Daily Sketch (27th March, 1895)

There was an astonishing sight in the neighbourhood of the Nightingale Lane Ground, Crouch End, on Saturday afternoon. Crouch End itself rubbed its eyes and pinched its arms. The intelligent foreigner might have been excused for imagining some State function was taking place - a Drawing-Room, for example. All through the afternoon train-loads of excited people journeyed over from all parts, and the respectable array of carriages, cabs, and other vehicles marked a record in the history of Football. Yet all that this huge throng of ten thousand had gathered to see was the opening match of the British Ladies' Football Club.

It would be idle to attempt any description of the play. The first few minutes were sufficient to show that football by women, if the British Ladies be taken as a criterion, is totally out of the question. A footballer requires speed, judgement, skill, and pluck. Not one of these four qualities was apparent on Saturday. For the most part, the ladies wandered aimlessly over the field at an ungraceful jog-trot. A smaller ball than usual was utilised, but the strongest among them could propel it no further than a few yards. The most elementary rules of the game were unknown, and the referee, Mr. C. Squires, spent a most agonising time.

(4) The Sporting Man (4th April, 1895)

I really think the public have taken the wrong view of the lady footballers. They are either universally condemned in good set terms, or are satired unmercifully. Of course, everybody knows that they did not play good football - if, indeed, they played football at all - but who could expect it? If we were to take a similar number of young men at random, who knew nothing about the game, and give them a few days practice before asking them to perform in public, could we expect any more science than we saw in the North v. South match? True, young men would run harder and kick more strongly, but, beyond this, I cannot believe that they would show any greater knowledge of the game or skill in its execution. I don't think the lady footballer is to be snuffed out by a number of leading articles written by old men out of sympathy both with football as a a game and the aspirations of the young new women. If the lady footballer dies, she will die hard.

(5) The Sporting Man (22nd April, 1895)

Their costumes had been chosen with all the good taste which women are supposed to display in the arranging of style and plenty of colours. The orthodox jerseys were made the basis of the attire, but it was seen that a great deal had been left to the coquetry and taste of the wearers. In many instances they were made loose after the manner of blouses and were relieved at the edges by a little white embroidering. Some of the sleeves, too, were made extremely wide, being evidently made after a decidedly fashion-plate pattern. There was the same variety in the make of the knickers. This would seem to be a personal matter for the ladies themselves. Several of them probably more advanced in reformed dress ideas than their sisters, wore the lower garments in the ordinary football fashion. Others. probably from feelings of modesty, had made a compromise by wearing the trousers of such wide dimensions as almost to resemble an ample divided skirt. Despite this difference in the cut of the garments, however, the young women presented a pretty appearance on the field, and this was in a great measure due to the nice assortment of colours, as well as the dainty way in which the women set them off. The jerseys of one side were of dark red, relieved with white, and were a nice contrast to the dark and pale blue costumes of the other side. Perhaps it was an accident, but it was a curious fact that the wearers of the red costumes were mostly brunettes, while several of the blue-jersied players were blondes. The ladies, no doubt, knew what colour best suited them, and certain it was that they appeared to the best advantage. One or two of the players wore dainty white gloves, while in several other instances the ladies allowed their hair to hang down their backs.

(6) The Brighton Argus reported on the teams that represented North and South London in the game at Preston Park (April, 1895)

North:- Rosa Thiere, goal; Nettie Honeyball and Lily Lynn, backs; P. Smith and F.B. Fenn, half-backs; Ruth Coupland, Edwards, Nellie Gilbert and Daisy Allen, forwards; South:- Clark, goal; Eva Roberts and M. Ellis, backs; Clarence and E. Potter, half-backs; F. Clark, Flo Hunt, A. F. Lewis, Mrs Kembell and A. J. Lewis, forwards.

(7) Football Bits Magazine (October, 1921)

It is an interesting question as to whether girls' schools should take up football. Personally I should hesitate to introduce football among very young girls. It has been done, however, in one or two schools and with success. Football is more strenuous than the usual games played at schools, and for very young girls to play might involve the risk of doing them harm internally. Most ladies' football clubs, I know, have young players and often they are very good. The Dick, Kerr's star player, Lily Parr, is only 16; and Miss Chorley, the clever little centre-forward of the St Helens team, is 16. Indeed there are few clubs which haven't 16- and l7year-old players.

On the other hand, the Atalanta club have a rule that no girl under 18 may play football, and I think such a rule is wise. The girl may seem to stand the strain all right, but it is probable that she will suffer later in life. On the whole, if football is to be introduced into schools, I think it should only be played at the colleges where the girls are usually in their late teens or early twenties.

(8) Ada Beaumont of Huddersfield Atalanta Club, quoted by David J. Williamson in Belles of the Ball (1991)

In the beginning they were mostly teachers, secretaries, young women who thought they were something, you know. A very high opinion of their own capacity and all that sort of thing. Well, that didn't go down very well with me. I never liked a show-off in anything. There weren't a right lot of us in the club who were what you might call manual workers, but we were the ones who played the football, you see, because we were used to the hard knocks in life. What you might call the rough 'eads!"

(9) Lancashire Daily Post (27th December, 1917)

After the Christmas dinner the crowd were in the right humour for enjoying this distinctly war-time novelty. There was a tendency amongst the players at the start to giggle, but they soon settled down to the game in earnest. Dick, Kerr's were not long in showing that they suffered less than their opponents from stage fright, and they had a better all round idea of the game. Woman for woman they were also speedier, and had a larger share of that quality, which in football slang is known as "heftiness". Quite a number of their shots at goal would not have disgraced the regular professional except in direction, and even professionals have been known on occasion to be a trifle wide of the target. Their forward work, indeed was often surprisingly good, one or two of the ladies displaying quite admirable ball control, whilst combination was by no means a negligible quality. Coulthards were strongest in defence, the backs battling against long odds, never giving in, and the goalkeeper doing remarkably well, but the forwards who were understood to have sadly disappointed their friends, were clearly affected with nerves.

All the conventions were duly honoured. The teams on making their appearance (after being photographed) indulged in "shooting in", and the rival captains, before tossing the coin for choice of ends, shook hands in the approved manner. At first the spectators were inclined to treat the game with a little too much levity, and they found amusement in almost everything from the pace, which until they got used to it, has the same effect as a slow moving Kinema-picture, to the "how dare you" expression of a player when she was pushed by an opponent. But when they saw that the ladies meant business, and were "playing the game" they readily took up the correct attitude and impartially cheered and encouraged each side. Within five minutes Dick, Kerr's had scored through Miss Whittle, and before half time they added further goals by Miss Birkins, a fine shot from 15 yards out, just under the bar, and Miss Rance. Coulthards who were quite out of the picture in the first half "bucked up" after the interval, and quite deserved a goal, but it was denied them, much to the disappointment of the spectators. They had a rare opportunity from a penalty in the last few minutes, but the ball was kicked straight at the keeper. On the other hand, Dick, Kerr's added to their score, Miss Rance running through and netting whilst the backs were "arguing" about some alleged offence, a natural touch which greatly delighted the onlookers. Mr John Lewis plied the whistle with discretion, whilst keeping within the four corners of the law, though he was clearly in a dilemma, probably for the first time in his official career, when one of the players was "winded" by the ball.

(10) Alice Woods, quoted by David J. Williamson in Belles of the Ball (1991)

They were organising a football competition at the factory, a sort of trials to choose who was to play in the team. I was asked to take part, and was very keen to do so, but it was a last minute thing and I didn't have any proper boots with me. Anyway, I played in my working shoes and they took quite a battering as you can imagine. My mother went up the wall when she found out.

(11) Letter signed "Centre Forward" that appeared in the Daily Herald in December, 1921.

I am not sure if I'm a womanly woman and I can't ask George Robey because we haven't been introduced. But I do like a man to be a man. I should not like him nearly so much if he were an elephant or a dromedary or anything like that. I like him to be manly. I cannot bear to see a clean-limbed Englishman in immaculate flannels stand about in a field doing nothing, sometimes for hours and hours, while he might be brightening cricket up and at the same time toning up his virility by wrestling. And why does the `referee' wear spotless white linen and blow a whistle instead of rolling in the mud or hacking somebody? He might be a womanly woman. And it reduces me to despair when I see a man playing the violin. Why doesn't he bash somebody over the head with it to prove he is a man?Cannot the rot be stopped in our nation's manhood? There is a way but so revolutionary that no other paper would, I am sure, print it. Why not leave the men to decide what's manly and what isn't?I am afraid, however, that this is a very silly suggestion or, of course, the FA would have thought of it.

(12) Ada Beaumont of Huddersfield Atalanta Club, quoted by David J. Williamson in Belles of the Ball (1991)

"We played on the (Huddersfield) Town ground, we trained down there and the fellas were smashing. For several occasions they would take the girl who played their position and try and teach them. There was a good centre half who took my sister under his wing. We made quite a good team up that way. I trained with Billy Smith the International. They all did it voluntarily, but they seemed to enjoy it all the same, and so did we.

(13) Frank Walt, Secretary of Newcastle United (December, 1921)

The game of football is not a woman's game and though it was permitted on professional grounds as a novelty arising out of women's participation in war work and as a novelty with charitable motives. The time has come when the novelty has worn off and the charitable motives are being lost sight of, so that the use of the professionals' ground is rightly withdrawn. The women's games have developed into commercial concerns and the expenses they reckon it would cost to play would not have left much for charity.

(14) Major Cecil Kent, former Secretary of Liverpool (December, 1921)

I may mention that in present and past seasons I have watched about 30 ladies' football matches between various teams and I have met the players. I have travelled with them frequently by road and rail and I have attended the various functions to which they have been invited, and I have met the local Lord Mayors and also the officials of the local charities and football clubs concerned. On all sides I have heard nothing but praise for the good work the girls are doing and the high standard of their play. The only thing I now hear from the man in the street is "Why have the FA got their knife into girls' football? What have the girls done except raise large sums for charity and play the game? Are their feet heavier on the turf than the men's feet?"

(15) David J. Williamson, Belles of the Ball (1991)

There is immense irony in the fact that it should be the Football Association of England, birthplace of the ladies' game, that should prove to be the oppressor, lacking the vision and flexibility of its foreign counterparts. The French authorities not only gave every encouragement to ladies' football in their own country, in spite of the fact that it was some way behind the English game, but it also rendered substantial financial aid. Unlike the authorities and a certain amount of `experts' in England, the French were thoroughly convinced that football was a healthy recreation for women...

In England, however, disappointment and confusion was the order of the day. All the ladies felt angry and hurt at the way they had been treated, cheated of the right to play a game they had come to love. Not only had they been openly accused of fraud and some kind of underhand dealing, hut also their ability to play what to them was just another game had been questioned in the press and in public debate as if they were some kind of fairground attraction. It had all come as very much of a shock, a mixture of disbelief and outrage that they should he treated in such a manner as this.

All the majority of lady foothallers had ever wanted to do was to simply play football! Over the years since the First World War they had given so much and asked very little in return. To he accused of, in effect, dipping their fingers in the till, only left them disgusted. Now that they had been officially banned the ladies would need to do an awful lot of thinking. To merely carry on and play the game would he more a question of survival than enjoyment. To achieve this new goal the ladies would need the guts and determination they had shown thus far. All the enthusiasm for the game that had so endeared them to the thousands of spectators at the charity matches now had to he brought to bear on simply keeping the game itself alive, if that was at all possible.

(16) Alfred Frankland, Sports Pictures Magazine (January, 1922)

We have always made a special point - in fact it is a resolution of our club committee - that we must never apply for a ground for a charity match. Those responsible for the charity must make all the arrangements themselves and accept all responsibility for payments made in connection with the match. All we have received wherever we played has been just our expenses, and in no way include any pecuniary recompense for playing. Never has any of our players received any payment which could be regarded as a match fee. The biggest sum any girl has ever received is lOs a day to compensate her for loss of work. No official of the club has ever received a penny-piece in the shape of honorarium, so that there can be no suggestion on any grounds whatsoever, that anyone associated with club has ever made anything out of it. Our sole ambition has been to help as much as we possibly could the numerous charities on whose behalf we have been asked to play. We have all given our services gladly and the girls have revelled in the football.

(17) The Washington Post (23rd September, 1922)

Quebec, September 22nd - The Dick, Kerr's team of English women soccer football players arrived today on the steamship Montclare en route to the United States where they will play a series of games.The girls will not be allowed to play Canadian soccer teams under order from the Dominion Football Association which objects to women football players.The team's first game will be at Patterson, N.J., on September 24th.

(18) The Washington Post (9th October, 1922)

The fair kickers of the Dick, Kerr's women's soccer club of Preston, England, lived up to their reputation yesterday at American League Park when they battled the Washington soccer eleven to a 4 to 4 draw. The women showed a fairly good dribbling game, but their kicking lacked both speed and force. The Washington kickers were extended most of the way. Although the men players, through good team work were given many opportunities they were not successful in registering goals, due to the brilliant defence of Miss Carmen Pomies, the Preston goalkeeper. She checked eleven of the fifteen attempts made by the local booters.Miss Lilly Parr, at outside left, put up an aggressive game registering two goals in seven tries she had at the net. The girls were able to penetrate the Washington right wing with success, but were checked several times on attempts at the left wing and midfield. The District kickers counted first, Green placing one past Miss Pomier after 26 minutes of play. Miss Parr evened it up shortly before half time. The second half was rather loosely played by both clubs, but the women showed to better advantage with teamwork.

(19) Football Association Website (2007)

December 1921: The Football Association banned women from playing on Football League grounds. Although there were discrepancies to be found in the accounts, the main reason was that: "Complaints have been made as to football being played by women, the council feel impelled to express their strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged." Though the game continued there was a great decrease in interest.