Nettie Honeyball

Nettie Honeyball helped to pioneer women's football in England. In 1894 Honeyball placed an advert in the press and persuaded about 30 young women to join the British Ladies Football Club.

Honeyball persuaded J. W. Julian, who played for Tottenham Hotspur, to coach the women. The training sessions took place twice a week at a park next to the Alexandra Park racecourse at Hornsey.

Honeyball gave an interview to the Daily Sketch on February, 1895, where she explained the reasons why she established the football club: "I founded the association late last year, with the fixed resolve of proving to the world that women are not the ‘ornamental and useless’ creatures men have pictured. I must confess, my convictions on all matters where the sexes are so widely divided are all on the side of emancipation, and I look forward to the time when ladies may sit in Parliament and have a voice in the direction of affairs, especially those which concern them most."

Florence Dixie, the youngest daughter of the Marquis of Queensbury and another committed feminist, agreed to become president of the British Ladies Football Club on condition that "the girls should enter into the spirit of the game with heart and soul."

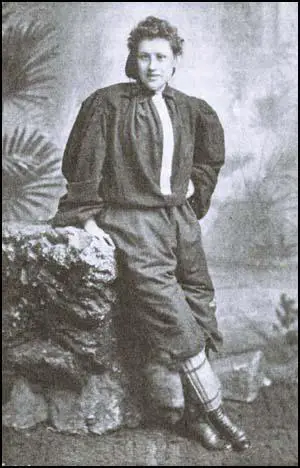

A decision had to be made about what the women would wear in games. One newspaper reporter explained: "The orthodox jerseys were made the basis of the attire, but it was seen that a great deal had been left to the coquetry and taste of the wearers. In many instances they were made loose after the manner of blouses and were relieved at the edges by a little white embroidering. Some of the sleeves, too, were made extremely wide, being evidently made after a decidedly fashion-plate pattern. There was the same variety in the make of the knickers. This would seem to be a personal matter for the ladies themselves. Several of them probably more advanced in reformed dress ideas than their sisters, wore the lower garments in the ordinary football fashion."

The first official match played by women took place at Crouch End in London on 23rd March, 1895. The girls were organized into teams that represented North and South London. The Manchester Guardian reported: "Their costumes came in for a good deal of attention.... one or two added short skirts over their knicker-bockers.... When the novelty has worn off, I do not think women's football will attract the crowds."

The Daily Sketch reporter claimed: "The first few minutes were sufficient to show that football by women, if the British Ladies be taken as a criterion, is totally out of the question. A footballer requires speed, judgement, skill, and pluck. Not one of these four qualities was apparent on Saturday. For the most part, the ladies wandered aimlessly over the field at an ungraceful jog-trot." North London (red), beat South London (light and dark-blue) 7-1.

The Sportsman newspaper was much more supportive: "True, young men would run harder and kick more strongly, but, beyond this, I cannot believe that they would show any greater knowledge of the game or skill in its execution. I don't think the lady footballer is to be snuffed out by a number of leading articles written by old men out of sympathy both with football as a a game and the aspirations of the young new women. If the lady footballer dies, she will die hard."

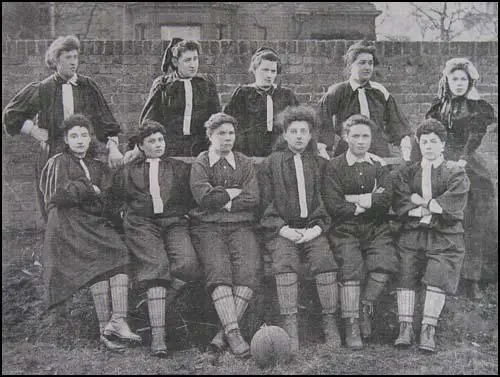

is second from the left in the top row.

The game was condemned by the male establishment. The British Medical Journal published an article condemning who played football: "We can in no way sanction the reckless exposure to violence, of organs which the common experience of women had led them in every way to protect."

On 6th April 1895 the British Ladies Football Club played at Preston Park in Brighton. The event was organised to raise funds for local medical charities. This time the North beat the South 8-3.

The next game was played in Bury. Over 5,000 people turned up to see the game and around £100 was raised for charity. This time the score was 3-3. Like in the other two games, Daisy Allen, the North's left-winger, was the outstanding player on view. The Bury Times described her as "a little sprite of four feet". According to one newspaper report, Daisy Allen was only 11 years old.

On Easter Monday 1895, Honeyball took the British Ladies Football Club to play on the ground used by Reading in the Southern League. The Berkshire Chronicle reported that a record crowd watched the game, beating the previous best, a league game between Reading and Luton Town. Rosa Thiere of the North team scored the only goal of the game.

The following day the club played at Ashton Gate in Bristol. This time the South beat the North 5-2. The Bristol Times was only impressed with the performance of one player. Daisey Allen was described as a "plucky youngster... who charged her bigger companions with great courage, and showed by her play that she had mastered the rudiments of the game, which could not be said for all."

After playing in New Brompton and Walsall, the British Ladies Football Club visited Newcastle where they played at the famous St. James's Park. Over 8,000 people saw the North win 4-3. Other games took place in South Shields and Darlington before playing at Jesmond. This time only 400 people turned up to watch and local newspapers reported that the novelty of watching women players appeared to be wearing off. Honeyball's group returned home to London and the first attempt to popularize women's football had come to an end.

Primary Sources

(1) Nettie Honneyball, interviewed in the Daily Sketch (February, 1895)

I founded the association late last year, with the fixed resolve of proving to the world that women are not the ‘ornamental and useless’ creatures men have pictured. I must confess, my convictions on all matters where the sexes are so widely divided are all on the side of emancipation, and I look forward to the time when ladies may sit in Parliament and have a voice in the direction of affairs, especially those which concern them most."

(2) Jarrow Express (29th March, 1895)

The members of the British Ladies' Football Club have played their first match in public. We hope (severely, says The Standard) it will be their last. There will always be curiosity to see women do unwomanly things, and it is not surprising that the match was attended by a crowd numbering several thousands, very few of whom would like to have their own sisters or daughters exhibiting themselves on the football field. Some of these young persons appeared to possess only an elementary knowledge of the game and its laws, and, for the present at all events, the club is quite unlikely to attract spectators for the sake of the play. How long it will continue to attract them for reasons unconnected with sport is another matter, but it is significant that a considerable proportion of those present left the field at half-time. The laughter was easy, and the amusement was rather coarse; but these are waning delights, and we shall be surprised if a second display wins even so equivocal a success as the first.

(3) Daily Sketch (27th March, 1895)

There was an astonishing sight in the neighbourhood of the Nightingale Lane Ground, Crouch End, on Saturday afternoon. Crouch End itself rubbed its eyes and pinched its arms. The intelligent foreigner might have been excused for imagining some State function was taking place - a Drawing-Room, for example. All through the afternoon train-loads of excited people journeyed over from all parts, and the respectable array of carriages, cabs, and other vehicles marked a record in the history of Football. Yet all that this huge throng of ten thousand had gathered to see was the opening match of the British Ladies' Football Club.

It would be idle to attempt any description of the play. The first few minutes were sufficient to show that football by women, if the British Ladies be taken as a criterion, is totally out of the question. A footballer requires speed, judgement, skill, and pluck. Not one of these four qualities was apparent on Saturday. For the most part, the ladies wandered aimlessly over the field at an ungraceful jog-trot. A smaller ball than usual was utilised, but the strongest among them could propel it no further than a few yards. The most elementary rules of the game were unknown, and the referee, Mr. C. Squires, spent a most agonising time.

(4) Sporting Man (4th April, 1895)

I really think the public have taken the wrong view of the lady footballers. They are either universally condemned in good set terms, or are satired unmercifully. Of course, everybody knows that they did not play good football - if, indeed, they played football at all - but who could expect it? If we were to take a similar number of young men at random, who knew nothing about the game, and give them a few days practice before asking them to perform in public, could we expect any more science than we saw in the North v. South match? True, young men would run harder and kick more strongly, but, beyond this, I cannot believe that they would show any greater knowledge of the game or skill in its execution. I don't think the lady footballer is to be snuffed out by a number of leading articles written by old men out of sympathy both with football as a a game and the aspirations of the young new women. If the lady footballer dies, she will die hard.

(5) Sporting Man (22nd April, 1895)

Their costumes had been chosen with all the good taste which women are supposed to display in the arranging of style and plenty of colours. The orthodox jerseys were made the basis of the attire, but it was seen that a great deal had been left to the coquetry and taste of the wearers. In many instances they were made loose after the manner of blouses and were relieved at the edges by a little white embroidering. Some of the sleeves, too, were made extremely wide, being evidently made after a decidedly fashion-plate pattern. There was the same variety in the make of the knickers. This would seem to be a personal matter for the ladies themselves. Several of them probably more advanced in reformed dress ideas than their sisters, wore the lower garments in the ordinary football fashion. Others. probably from feelings of modesty, had made a compromise by wearing the trousers of such wide dimensions as almost to resemble an ample divided skirt. Despite this difference in the cut of the garments, however, the young women presented a pretty appearance on the field, and this was in a great measure due to the nice assortment of colours, as well as the dainty way in which the women set them off. The jerseys of one side were of dark red, relieved with white, and were a nice contrast to the dark and pale blue costumes of the other side. Perhaps it was an accident, but it was a curious fact that the wearers of the red costumes were mostly brunettes, while several of the blue-jersied players were blondes. The ladies, no doubt, knew what colour best suited them, and certain it was that they appeared to the best advantage. One or two of the players wore dainty white gloves, while in several other instances the ladies allowed their hair to hang down their backs.

(6) Brighton Argus reported on the teams that represented North and South London in the game at Preston Park (April, 1895)

North:- Rosa Thiere, goal; Nettie Honeyball and Lily Lynn, backs; P. Smith and F.B. Fenn, half-backs; Ruth Coupland, Edwards, Nellie Gilbert and Daisy Allen, forwards; South:- Clark, goal; Eva Roberts and M. Ellis, backs; Clarence and E. Potter, half-backs; F. Clark, Flo Hunt, A. F. Lewis, Mrs Kembell and A. J. Lewis, forwards.

(7) Barbara Jacobs, The Dick, Kerr's Ladies (2004)

Across Scotland, there was a tradition of married women of a town or village playing regular matches against single women as a way for the male onlookers to select a lusty bride. And in 1895 a deliciously-named woman, Nettie Honeyball, an educated, middle-class feminist and leading sportswoman of her day, arranged a fixture between the North and South of England Ladies at Crouch End. In the same year, Lady Florence Dixie was touring Scotland with a women's football team she managed. But nevertheless, sports provision for girls and women was largely organized according to social status.