The Battle of Cable Street

Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, the press baron, was a great supporter of Adolf Hitler. According to James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979): "Shortly after the Nazis' sweeping victory in the election of September 14, 1930, Rothermere went to Munich to have a long talk with Hitler, and ten days after the election wrote an article discussing the significance of the National Socialists' triumph. The article drew attention throughout England and the Continent because it urged acceptance of the Nazis as a bulwark against Communism... Rothermere continued to say that if it were not for the Nazis, the Communists might have gained the majority in the Reichstag." (1)

Louis P. Lochner, argues in his book, Tycoons and Tyrant: German Industry from Hitler to Adenauer (1954) that Lord Rothermere provided funds to Hitler via Ernst Hanfstaengel. When Hitler became Chancellor on 30th January 1933, Rothermere produced a series of articles acclaiming the new regime. "I urge all British young men and women to study closely the progress of the Nazi regime in Germany. They must not be misled by the misrepresentations of its opponents. The most spiteful distracters of the Nazis are to be found in precisely the same sections of the British public and press as are most vehement in their praises of the Soviet regime in Russia." (2)

George Ward Price, the Daily Mail's foreign correspondent developed a very close relationship with Adolf Hitler. According to the German historian, Hans-Adolf Jacobsen: "The famous special correspondent of the London Daily Mail, Ward Price, was welcomed to interviews in the Reich Chancellery in a more privileged way than all other foreign journalists, particularly when foreign countries had once more been brusqued by a decision of German foreign policy. His paper supported Hitler more strongly and more constantly than any other newspaper outside Germany." (3)

The Daily Mail and the National Union of Fascists

Franklin Reid Gannon, the author of The British Press and Germany (1971), has claimed that Hitler regarded him as "the only foreign journalist who reported him without prejudice". (4) In his autobiography, Extra-Special Correspondent (1957), Ward Price defended himself against the charge he was a fascist by claiming: "I reported Hitler's statements accurately, leaving British newspaper readers to form their own opinions of their worth." (5)

Lord Rothermere also gave full support to Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. He wrote an article, Hurrah for the Blackshirts, on 22nd January, 1934, in which he praised Mosley for his "sound, commonsense, Conservative doctrine". Rothermere added: "Timid alarmists all this week have been whimpering that the rapid growth in numbers of the British Blackshirts is preparing the way for a system of rulership by means of steel whips and concentration camps. Very few of these panic-mongers have any personal knowledge of the countries that are already under Blackshirt government. The notion that a permanent reign of terror exists there has been evolved entirely from their own morbid imaginations, fed by sensational propaganda from opponents of the party now in power. As a purely British organization, the Blackshirts will respect those principles of tolerance which are traditional in British politics. They have no prejudice either of class or race. Their recruits are drawn from all social grades and every political party. Young men may join the British Union of Fascists by writing to the Headquarters, King's Road, Chelsea, London, S.W." (6)

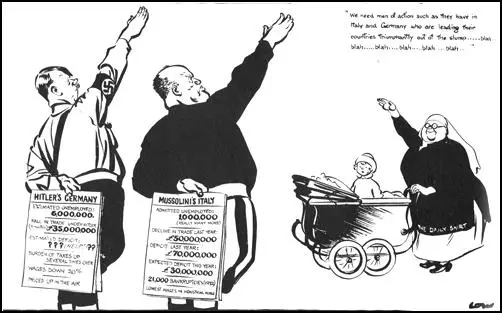

David Low, a cartoonist employed by the Evening Standard, made several attacks on Rothermere's links to the fascist movement. In January 1934, he drew a cartoon showing Rothermere as a nanny giving a Nazi salute and saying "we need men of action such as they have in Italy and Germany who are leading their countries triumphantly out of the slump... blah... blah... blah... blah." The child in the pram is saying "But what have they got in their other hands, nanny?" Hitler and Mussolini are hiding the true records of their periods in government. Hitler's card includes, "Hitler's Germany: Estimated Unemployed: 6,000,000. Fall in trade under Hitler (9 months) £35,000,000. Burden of taxes up several times over. Wages down 20%." (7)

Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Evening Standard, was a close friend and business partner of Lord Rothermere, and refused to allow the original cartoon to be published. At the time, Rothermere controlled forty-nine per cent of the shares. Low was told by one of Beaverbrook's men: "Dog doesn't eat dog. It isn't done." Low commented that it was said as "though he were giving me a moral adage instead of a thieves' wisecrack." He was forced to make the nanny unrecognizable as Rothermere and had to change the name on her dress from the Daily Mail to the Daily Shirt. (8)

The Daily Mail continued to give its support to the fascists. Lord Rothermere allowed fellow member of the January Club, Sir Thomas Moore, the Conservative Party MP for Ayr Burghs, to publish pro-fascist articles in his newspaper. Moore described the BUF as being "largely derived from the Conservative Party". He added "surely there cannot be any fundamental difference of outlook between the Blackshirts and their parents, the Conservatives?" (9)

In April 1934, The Daily Mail published an article by Randolph Churchill that praised a speech that Mosley made in Leeds: "Sir Oswald's peroration was one of the most magnificent feats of oratory I have ever heard. The audience which had listened with close attention to his reasoned arguments were swept away in spontaneous reiterated bursts of applause." (10)

Violence and the British Union of Fascists

The London Evening News, another newspaper owned by Harold Harmsworth, 1st Lord Rothermere, found a more popular and subtle way of supporting the Blackshirts. It obtained 500 seats for a BUF rally at the Royal Albert Hall and offered them as prizes to readers who sent in the most convincing reasons why they liked the Blackshirts. Rothermere's , The Sunday Dispatch, even sponsored a Blackshirt beauty competition to find the most attractive BUF supporter. Not enough attractive women entered and the contest was declared void. (11)

David Low was one of those who attended the meeting at the Royal Albert Hall: "Mosley spoke effectively at great length. Delivery excellent, matter reckless. Interruptions began, but no dissenting voice got beyond half a dozen sentences before three or four bullies almost literally jumped on him, bashed him and lugged him out. Two such incidents happened near me. An honest looking blue-eyed student type rose and shouted indignantly 'Hitler means war!' whereupon he was given the complete treatment." (12)

Nicholas Mosley pointed out that his father was an outstanding communicator: "He had an amazing memory for figures. He liked to be challenged by hecklers, because he felt confident in his powers of repartee. But above all what held his audiences and almost physically lifted them were those mysterious rhythms and cadences which a mob orator uses and which, combined with primitively emotive words, play upon people's minds like music. This power that Oswald Mosley had with words did not always, in the long run, work to his advantage. There were times when his audience was being lifted but he himself was being lulled into thinking the reaction more substantial than it was. After the enthusiasm had worn off like the effects of a drug an audience was apt to find itself feeling rather empty. (In the same way his girlfriends, one of them (Georgia Sitwell) once said, would feel somewhat ashamed after having been seduced.)" (13)

Oswald Mosley decided to hold a large British Union of Fascists rally at Olympia on 7th June, 1934. Soon after the meeting was announced, The Daily Worker issued a statement declaring that the Communist Party of Great Britain intended to demonstrate against Mosley by organized heckling inside the meeting and by a mass demonstration outside the hall. (14)

The CPGB did what it could to disrupt the meeting. As Robert Benewick, the author of The Fascist Movement in Britain (1972) pointed out: "They (the CPGB) printed illegal tickets. Groups of hecklers were stationed at strategic points inside the meeting, and Press interviews with their members were organized outside. First-aid stations were set up in near-by houses, and there were the inevitable parades, banners, placards and slogans. It was unlikely that weapons were officially authorized but this would not have prevented anyone from carrying them." (15) In fact, Philip Toynbee later admitted that he and Esmond Romilly both took knuckle-dusters to the meeting. (16)

About 500 anti-fascists including Vera Brittain, Richard Sheppard and Aldous Huxley, managed to get inside the hall. When they began heckling Oswald Mosley they were attacked by 1,000 black-shirted stewards. Several of the protesters were badly beaten by the fascists. Margaret Storm Jameson pointed out in The Daily Telegraph: "A young woman carried past me by five Blackshirts, her clothes half torn off and her mouth and nose closed by the large hand of one; her head was forced back by the pressure and she must have been in considerable pain. I mention her especially since I have seen a reference to the delicacy with which women interrupters were left to women Blackshirts. This is merely untrue... Why train decent young men to indulge in such peculiarly nasty brutality?" (17)

Collin Brooks, was a journalist who worked for Lord Rothermere at the The Sunday Dispatch. He also attended the the rally at Olympia. Brooks wrote in his diary: "He (Mosley) mounted to the high platform and gave the salute - a figure so high and so remote in that huge place that he looked like a doll from Marks and Spencer's penny bazaar. He then began - and alas the speakers hadn't properly tuned in and every word was mangled. Not that it mattered - for then began the Roman circus. The first interrupter raised his voice to shout some interjection.The mob of storm troopers hurled itself at him. He was battered and biffed and hashed and dragged out - while the tentative sympathisers all about him, many of whom were rolled down and trodden on, grew sick and began to think of escape. From that moment it was a shambles. Free fights all over the show. The Fascist technique is really the most brutal thing I have ever seen, which is saving something. There is no pause to hear what the interrupter is saying: there is no tap on the shoulder and a request to leave quietly: there is only the mass assault. Once a man's arms are pinioned his face is common property to all adjacent punchers." Brooks also commented that one of his "party had gone there very sympathetic to the fascists and very anti-Red". As they left the meeting he said "My God, if ifs to be a choice between the Reds and these toughs, I'm all for the Reds". (18)

Several members of the Conservative Party were in the audience. Geoffrey Lloyd pointed out that Mosley stopped speaking at once for the most trivial interruptions, although he had a battery of twenty-four loud-speakers. The interrupters were then attacked by ten to twenty stewards. Mosley's claim that he was defending the right of freedom was "pure humbug" and his tactics were calculated to provide an "apparent excuse" for violence. (19) William Anstruther-Gray, the MP for North Lanark, agreed with Lloyd: "Frankly if anybody had told me an hour before the meeting at Olympia that I should find myself on the side of the Communist interrupters, I would have called him a liar." (20)

However, George Ward Price, of The Daily Mail disagreed and put all the blame on the demonstrators: "If the Blackshirts movement had any need of justification, the Red Hooligans who savagely and systematically tried to wreck Sir Oswald Mosley's huge and magnificently successful meeting at Olympia last night would have supplied it. They got what they deserved. Olympia has been the scene of many assemblies and many great fights, but never had it offered the spectacle of so many fights mixed up with a meeting." (21)

In the debate that took place in the House of Commons on the BUF rally, several Tory MPs defended Mosley. Michael Beaumont by admitting that he was an "anti-democrat and an avowed admirer of Fascism in other countries" and from what he observed inside the meeting, no one there "got anything more than he deserved". (22) Tom Howard, the MP for Islington South, admired Mosley for his determination to maintain the right of free speech. He was also worried that the BUF were taking members from the Tories: "The tens of thousands of young men who had joined the Blackshirts... are the best element of the country". (23)

Clement Attlee, the Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, claimed to have evidence to demonstrate that the Blackshirts used "plain-clothes inciters to disorder" at their meetings and that the Blackshirts used deliberate incitement as an excuse for force. (24) Walter Citrine, the General Secretary of the Trade Union Congress, demanded an end to "the drilling and arming of civilian sections of the community" and deplored the inactivity of the police and the courts in dealing with the British Union of Fascists." (25)

Stanley Baldwin, the prime minister, admitted that there were similarities between the Conservative Party and the British Union of Fascists but because of its "ultramontane Conservatism... it takes many of the tenets of our own party and pushes them to a conclusion which, if given effect to, would, I believe, be disastrous to our country." (26) The government rejected a proposal for a public inquiry into the violence at the Olympia meeting but the Home Secretary gave several hints on the possibility of legislation that would help prevent trouble at political meetings. (27)

In July, 1934 Lord Rothermere suddenly withdrew his support from Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. The historian, James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979), argues: "The rumor on Fleet Street was that the Daily Mail's Jewish advertisers had threatened to place their adds in a different paper if Rothermere continued the pro-fascist campaign." Pool points out that sometime after this, Rothermere met with Hitler at the Berghof and told how the "Jews cut off his complete revenue from advertising" and compelled him to "toe the line." Hitler later recalled Rothermere telling him that it was "quite impossible at short notice to take any effective counter-measures." (28)

Vernon Kell, of MI5, reported to the Home Office that the rally at Olympia appeared to have had a negative impact on the future of the British Union of Fascists: "It is becoming increasingly clear that at Olympia Mosley suffered a check which is likely to prove decisive. He suffered it, not at the hands of the Communists who staged the provocations and now claim the victory; but at the hands of Conservative MPs, the Conservative press and all those organs of public opinion which made him abandon the policy of using his Defence Force to overwhelm interrupters." (29)

Oswald Mosley had developed a large following in Sussex after the election of Charles Bentinck Budd, the fascists only councillor. Budd arranged for Mosley and William Joyce to address a meeting at the Worthing Pavilion Theatre on 9th October, 1934. The British Union of Fascists covered the town with posters with the words "Mosley Speaks", but during the night someone had altered the posters to read "Gasbag Mosley Speaks Tripe". It was later discovered that this had been done by Roy Nicholls, the chairman of the Young Socialists. (30)

Oswald Mosley Documentary

The venue was packed with fascist supporters from Sussex. According to Michael Payne: "Finally the curtain rose to reveal Sir Oswald himself standing alone on the stage. Clad entirely in black, the great silver belt buckle gleaming, the right arm raised in the Fascist salute, he was spell-bindingly illuminated in the hushed, almost reverential atmosphere by the glare of spotlights from right, left and centre. A forest of black-sleeved arms immediately shot up to hail him." (31)

The meeting was disrupted when a few hecklers were ejected by hefty East End bouncers. Mosley, however, continued his speech undaunted, telling his audience that Britain's enemies would have to be deported: "We were assaulted by the vilest mob you ever saw in the streets of London - little East End Jews, straight from Poland. Are you really going to blame us for throwing them out?" (32)

At the close of proceedings Mosley and Joyce, accompanied by a large body of blackshirts, marched along the Esplanade.They were protected by all nineteen available members of the Borough's police force. The crowd of protesters, estimated as around 2,000 people, attempted to block their path. A ninety-six-year-old woman, Doreen Hodgkins, was struck on the head by a Blackshirt before being escorted away. When the Blackshirts retreated inside, the crowd began to chant: "Poor old Mosley's got the wind up!" (33)

The Fascists went into Montague Street in an attempt to get to their headquarters in Anne Street. The author of Storm Tide: Worthing 1933-1939 (2008) has pointed out: "Sir Oswald, clearly out of countenance and feeling menaced, at once ordered his tough, battle-hardened bodyguards - all of imposing physique and, like their leader, towering over the policemen on duty - to close ranks and adopt their fighting stance which, unsurprisingly, as all were trained boxers, had been modelled on, and closely resembled, that of a prize fighter." (34)

Superintendent Clement Bristow later claimed that a crowd of about 400 people attempted to stop the Blackshirts from getting to their headquarters. Francis Skilton, a solicitor's clerk who had left his home at 30 Normandy Road to post a letter at the Central Post Office in Chapel Road, and got caught up in the fighting. A witness, John Birts, later told the police that Skilton had been "savagely attacked by at least three Blackshirts." (35)

According to The Evening Argus: "The fascists fought their way to Mitchell's Cafe and barricaded themselves inside as opponents smashed windows and threw tomatoes. As midnight loomed, they broke out and marched along South Street to Warwick Street. One woman bystander was punched in the face in what witnesses described as 'guerrilla warfare'. There were casualties on both sides as a 'seething, struggling mass of howling people' became engaged in running battles. People in nightclothes watched in amazement from bedroom windows overlooking the scene." (36)

The next day the police arrested Oswald Mosley, Charles Budd, William Joyce and Bernard Mullans and accused them of "with others unknown they did riotously assemble together against the peace". The court case took place on 14th November 1934. Charles Budd claimed that he telephoned the police three times on the day of the rally to warn them that he believed "trouble" had been planned for the event. A member of the Anti-Fascist New World Fellowship had told him that "we'll get you tonight". Budd had pleaded for police protection but only four men had turned up that night. He argued that there had been a conspiracy against the BUF that involved both the police and the Town Council.

Several witnesses gave evidence in favour of the BUF members. Eric Redwood - a barrister from Chiddingfield, said that the trouble was caused by a gang of "trouble-seeking roughs" and that Budd, Mosley, Joyce and Mullans "acted with admirable restraint". Herbert Tuffnell, a retired District Commissioner of Uganda, also claimed that it was the anti-fascists who started the fighting. (37)

Joyce, in evidence, said that "any suggestion that they came down to Worthing to beat up the crowd was ridiculous in the highest degree. They were menaced and insulted by people in the crowd." Mullans claimed that told an anti-fascist demonstrator that he "should be ashamed for using insulting language in the presence of women". The man then hit in the eye and he retaliated by punching the man in the mouth. (38)

John Flowers, the prosecuting council told the jury that "if you come to the conclusion that there was an organised opposition by roughs and communists and others against the Fascists... that this brought about the violence and that the defendants and their followers were protecting themselves against violence, it will not be my duty to ask you to find them guilty." The jury agreed and all the men were found not guilty. (39)

Oswald Mosley and Anti-Semitism

In the early days of the British Union of Fascist, Mosley began to express anti-Semitic comments. On one occasion, a BUF member, the Jewish boxer, Ted "Kid" Lewis (born Solomon Mendeloff), punched Mosley in the face after he admitted to being anti-Semitic. Harold Nicolson advised Mosley against following the policy of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany. He argued that an "openly anti-Semitic movement would be counter-productive, in terms of converting public opinion, because of Britain's underlying liberal culture." (40)

Mosley rejected this advice and began to make violent anti-Semitic speeches that received praise from Hitler. Mosley responded by sending Hitler a telegram: "Please receive my greatest thanks for your kind telegram in relation to my speech in Leicester, which was received while I was away from London. I esteem greatly your advice in the midst of our hard struggle. The forces of Jewish corruption must be overcome in all great countries before the future of Europe can be made secure in justice and peace. Our struggle to this end is hard, but our victory is certain." (41)

Mosley decided to develop a long-term electoral strategy of supporting anti-Semitic campaigns in Jewish areas. Of the 350,000 British Jews, about 230,000 lived in London, 150,000 of them in the East End. In October 1935, Mosley had ordered John Becket and A. K. Chesterton to promote anti-Semitism in those places with the highest number of Jews. (42) According to Robert Skidelsky, "Sixty thousand or so Jews were to be found in Stepney; another 20,000 or so in Bethnal Green; with smaller numbers in Hackney, Shoreditch and Bow." (43)

The BUF opened its first "London branch, in Bow, in October 1934, signalling its intent to build a populist, working-class, fascist movement especially in Irish-Catholic areas bordering Jewish communities. Mosley thought he was pushing an open door, encouraging anti-Semitism there. His emergent movement would have visible targets on which to vent their growing frustration about their own circumstances." (44)

Ernest Thurtle, the Labour MP for Shoreditch, warned that it was a very dangerous situation: "Fascist speakers... are talking to people who are frightfully discontented and suffering from misfortune, poverty and unemployment, and when these people hear speakers say that they are being robbed and exploited by Jewish shopkeepers, or that jobs which they should have had have been taken by Jewish workpeople, there is a clear danger that language of that kind and in such places is calculated to cause a breach of the peace." (45)

In March, 1936, the Labour Party M.P. Herbert Morrison, in the House of Commons, described how Jews in London and had been threatened and abused." In reply, John Simon, the Home Secretary, claimed that he "was not prepared to tolerate any form of Jew-baiting... and we are not in the least disposed to look with an indulgent eye on any form of persecution". However, he failed to take action against these Fascist speakers for causing a breach of the peace. (46)

Oswald Mosley was quoted in The Times as saying that claimed that John Simon was suggesting that the Jews were the only people in Great Britain immune from attack. and that it was illegal to incite others to violence, but felt that he had as much right to attack Jews on their conduct in Great Britain as the Labour Party had the right to attack anyone possessing capital. (47)

The Oxford University educated Jewish philanthropist Basil Henriques QC, who had been instrumental in setting up youth clubs for Jews in deprived areas, urged young people not to become involved in anti-fascist activities being organised by left-wing groups as it would be "playing into the hands of the enemy". (48) The Jewish Chronicle agreed and warned of the danger of driving "Jewish youth into the arms of extremist anti-fascists". (49)

David Rosenberg, the author of Rebel Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London's Radical History (2015), has pointed out that Mosley increased his attacks on the Jews. In one speech he "denounced Labour politicians inspired by the "German Jew", Karl Marx, Tories who admired "the Italian Jew" Benjamin Disraeli, and Liberals led by that "typical John Bull", Herbert Samuel. (50)

The BUF also became active in other cities with significant Jewish populations, including Manchester (35,000) and Leeds (30,000). This stimulated anti-fascist organizations. In September, 1936, a BUF march to Holbeck Moor, clashed with a hostile demonstration of 20,000 people in which Mosley and many other fascists were attacked and injured by missiles. (51)

In response to complaints from local Jewish residents, the Manchester police attended all fascist meetings and kept notes. However, they decided that BUF meetings were "conducted in a very orderly manner and without giving any cause for objection", and argued that trouble only arose if Jews attended and interrupted the speakers. At a meeting in Manchester in June 1936 Jock Houston referred to Jews as the international enemy, dominating banks and commerce and fomenting war between war between Britain and Germany. However, the Attorney General Donald Somervell, told complainants that no criminal offence had been committed." When Percy Harris, the Bethnal Green, M.P., complained about the BUF to the police he was told that they were not doing anything illegal, and as for Jew-baiting: "in this locality such speeches are fairly well received by the majority of the persons attending." (52)

The Morning Post criticised the Conservative Party for ignoring the activities of the BUF and praised the Labour Party for challenging the policies and activities of Mosley's party. (53) However, it was the Independent Labour Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain who became "the champions of the Jews in the ant-Fascist cause". The Jewish People's Council Against Fascism and Anti-Semitism, established in July, 1936, became the most important organization opposed to fascism. (54)

This organisations was often critical of the role played in the resistance to fascism by the Board of Deputies of British Jews. The leader of the new organisation, Aaron Rapoport Rollin, who was instrumental in establishing the Jewish People's Council, was also the chairman of the Jewish Labour Council, and a trade union leader in the garment industry, pointed out: "The Board of Deputies, constituted as it is on an obsolete and often farcical basis of representation, does not represent the widest elements of the Jewish people in this country... The mass of the Jewish people are not at all yet convinced that a complete and sincere change of heart and mind has taken place in the leadership of the Board. There must therefore be in existence a strong and virile popular Jewish body to act as a driving force in our fight against the dangers confronting us." (55)

The members of this new organisation were also critical of The Jewish Chronicle, whose "editorial policy was closely allied with that of the official leadership and other recognised figureheads of Anglo-Jewry, and gave prominence to their statements." When anti-fascists became engaged with physical encounters with fascists were deemed guilty of "stupid and disgraceful behaviour" and their actions characterised as a "rank disservice to the Jewish people". (56)

When Jews attempted to disrupt public meetings of the British Union of Fascists, the newspaper invoked Jewish theology in condemning Jews involved in the disturbances that were taking place: "Jews who interfere with the full expression of opinion are false to the Jewish teachings of justice and fair play and are traitors to the vital material interests of the Jewish people." (57) Lionel de Rothschild, the former Conservative Party MP and leading exponent of Zionism, and the most significant Jew in Britain, agreed with this approach and refused to make any statements in "opposition to fascism". (58)

The Jewish Chronicle especially resented left-wing groups from campaigning against the Fascists. After the publication of the Communist Party of Great Britain leaflet in Yiddish calling people to join a demonstration against the BUF in Hyde Park the newspaper reported: "We urge Jews who feel strongly to have nothing to do with the protests... stay away and refrain from adding to the sufficiently heavy anxieties of the police. Any Jew guilty of lack of restraint is not a good friend of his people or of the principles he professes to hold." (59) This plea was unsuccessful and an estimated 100,000 took part in the demonstration. (60)

The Battle of Cable Street

In an attempt to increase support for their campaign, the British Union of Fascists announced its attention of marching through the East End on 4th October 1936, wearing their Blackshirt uniforms. The Jewish People's Council Against Fascism and Anti-Semitism produced a petition that stated: "We the undersigned citizens of East London, view with grave concern the proposed march of the British Union of Fascists upon East London. The avowed object of the Fascist movement in Great Britain is the incitement of malice and hatred against sections of the population. It aims to further ends which seek to destroy the harmony and goodwill which has existed for centuries among the East London population, irrespective of differences in race and creed. We consider racial incitement, by a movement which employs flagrant distortions of the truth and degrading calumny and vilification, as a direct and deliberate provocation to attack. We therefore make an appeal to His Majesty's Secretary of State for Home Affairs to prohibit such matters and thus retain peaceable and amicable relations between all sections of East London's population." (61)

Within 48 hours over 100,000 people signed the petition and it was presented to 2nd October deputation was headed by James Hall, the Labour Party M.P. for Whitechapel, Father St John Beverley Groser and Alfred M. Wall (Secretary of the London Trades Council). (62) George Lansbury, the M.P. for Bow & Bromley, also wrote to John Simon, the Home Secretary, and asked for the march to be diverted. (63) Simon refused and told a deputation of local mayors that he would not interfere as he did not wish to infringe freedom of speech. Instead he sent a large police escort in an attempt to prevent anti-fascist protesters from disrupting the march. (64)

The Independent Labour Party responded by issuing a leaflet calling on East London workers to take part in the counter demonstration which assembles at Aldgate at 2.p.m. (65) As a result the anti-fascists, adopting the slogan of the Spanish Republicans defending Madrid "They Shall Not Pass" and developed a plan to block Mosley's route. One of the key organizers was Phil Piratin, a leading figure in the Stepney Tenants Defence League. Denis Nowell Pritt and other members of the Labour Party also took part in the campaign against the march. (66)

The Jewish Chronicle told its readers not to take part in the demonstration: "Urgent Warning. It is understood that a large Blackshirt demonstration will be held in East London on Sunday afternoon. Jews are urgently warned to keep away from the route of the Blackshirt march from their meetings. Jews who, however innocently, became involved in any possible disorders will be actively helping anti-Semitism and Jew-baiting. Unless you want to help the Jew-baiters - Keep Away." (67)

The Daily Herald reported that by "1.30 p.m.... anti-Fascists had massed in tens of thousands. They formed a solid block at the junction of Commercial Street, Whitechapel Road and Aldgate. It was through this area that Mosley would have to reach his goal, Victoria Park, Stepney and the Socialists, Jews and Communists of the East End were determined that 'Mosley should not pass!' At the time every available policeman - about 10,000 in all - was converging on Whitechapel from all parts of London. Mounted police rode into the huge throng and forced the demonstrators back into the streets. Cordons were then flung across to keep a clear space for the marchers." (68)

Father St John Beverley Groser, of Christ Church, Watney Street, was a Christian Socialist and was one of the main organisers of the demonstration. He was hit several times by police batons and suffered a broken nose. The Church authorities were very unhappy with his involvement and his licence to preach was removed for a time. He had been previously forced to resign from the church after supporting the trade union movement during the General Strike. (69)

By 2.00 p.m. 50,000, people had gathered to prevent the entry of the march into the East End, and something between 100,000 and 300,000 additional protesters waited on the route. Barricades were erected across Cable Street and the police endeavoured to clear a route by making repeated baton charges. (70) One of the demonstrators said that he could see "Mosley - black-shirted himself - marching in front of about 3,000 Blackshirts and a sea of Union Jacks. It was as though he were the commander-in-chief of the army, with the Blackshirts in columns and a mass of police to protect them." (71)

Eventually at 3.40 p.m. Sir Philip Game, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in London, had to accept defeat and told Mosley that he had to abandon their march and the fascists were escorted out of the area. Max Levitas, one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Stepney later pointed out: "It was the solidarity between the Labour Party, the Communist Party and the trade union movement that stopped Mosley's fascists, supported by the police, from marching through Cable Street." (72) William J. Fishman said: "I was moved to tears to see bearded Jews and Irish Catholic dockers standing up to stop Mosley. I shall never forget that as long as I live, how working-class people could get together to oppose the evil of fascism." (73)

The Manchester Guardian supported the Home Secretary's decision to allow the BUF's march as it demonstrated that the Fascists had the right to hold a procession, but correctly banned it, when it showed signs of getting out of control. (74) The Times condemned the actions of the anti-fascists and concluded, "that this sort of hooliganism must clearly be ended, even if it involves a special and sustained effort from the police authorities." (75) The Daily Telegraph praised the Police Commissioner Hugh Trenchard "as he was on the side of free speech, and those who assembled to resist the march threatened it." (76)

A total of 79 anti-fascists were arrested at during the Battle of Cable Street. Several of these men received a custodial sentence. This included the 21 year-old, Charlie Goodman. One of his prison experiences highlighted the conflict between the conservative Jewish establishment and left-wing Jews: "I was visited by a Mr Prince from the Jewish Discharged Prisoners Aid Society... an arm of the Board of Deputies who called all the Jewish prisoners together." He asked them what crimes they had committed. The first five or six prisoners admitted to crimes such as robbery and he replied, "Don't worry, we'll look after you." When he asked Goodman he replied, "fighting fascism". This provoked Prince into saying: "You are the kind of Jew who gives us a bad name... It is people like you that are causing all the aggravation to the Jewish people." (77)

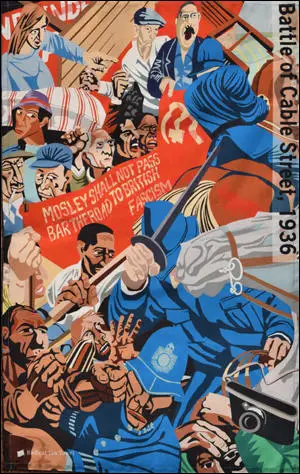

This tea towel design is based on part of The Battle of Cable Street mural

(painted onto the external west wall of St George's Town Hall, Cable Street,

London Borough of Tower Hamlets). The mural was begun in 1976 by Dave Binnington,

inspired by Mexican muralists, but he abandoned it in the face of racist vandalism.

It was finished by Ray Walker, Desmond Rochford and Paul Butler in 1987.

According to one police report, Mick Clarke, one of the fascist leaders in London told one meeting: "It is about time the British people of the East End knew that London's pogrom is not very far away now. Mosley is coming every night of the week in future to rid East London and by God there is going to be a pogrom." As John Bew has pointed out: "That was not the end of the matter. Labour Party meetings were frequently stormed by fascists over the following months. Stench bombs would be put through a window, doors would be kicked open, and fists would fly." (78)

The Aftermath

The Battle of Cable Street forced the government to reconsider its approach to the British Union of Fascists and passed the 1936 Public Order Act. This gave the Home Secretary the power to ban marches in the London area and police chief constables could apply to him for bans elsewhere. The 1936 Public Order Act also made it an offence to wear political uniforms and to use threatening and abusive words. Herbert Morrison of the Labour Party claimed this act "smashed the private army and I believe commenced the undermining of Fascism in this country." (79)

Oswald Mosley now decided to use democratic methods to take control of the East End of London. In February, 1937, Mosley announced that the British Union of Fascists would be taking part in London's municipal elections the following month. During the campaign BUF candidates attacked Jewish financiers, landlords, shopkeepers and politicians. Mosley also attacked the Labour Party for not solving London's housing problem. The main slogan of the BUF was "Vote British and Save London".

The election results announced on 6th March 1937 revealed that the BUF won only 18% of the votes cast in the seats they were contesting. Mick Clarke and Alexander Raven Thompson did best of all with winning 23% of the vote in Bethnal Green. This was less than half of those of the Labour candidates. The BUF vote mainly came from disillusioned supporters of the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party rather than that of Labour. This suggested "that Mosley had as yet made little political headway among the ordinary working-class of East London - dockers, transport men, shipyard workers." (80)

Primary Sources

(1) Petition organised by the Jewish People's Council Against Fascism and Anti-Semitism that was presented to the Home Office on 2nd October 1936.

We the undersigned citizens of East London, view with grave concern the proposed march of the British Union of Fascists upon East London. The avowed object of the Fascist movement in Great Britain is the incitement of malice and hatred against sections of the population. It aims to further ends which seek to destroy the harmony and goodwill which has existed for centuries among the East London population, irrespective of differences in race and creed. We consider racial incitement, by a movement which employs flagrant distortions of the truth and degrading calumny and vilification, as a direct and deliberate provocation to attack. We therefore make an appeal to His Majesty's Secretary of State for Home Affairs to prohibit such matters and thus retain peaceable and amicable relations between all sections of East London's population.

(2) The Daily Worker (3rd October 1936)

A deputation from the Jewish People's Council called at the Home Office yesterday morning to protest against the march arranged by the British Union of Fascists to take place in the East End of London on Sunday. They are also submitting a petition against the march, bearing over 100,000 signatures obtained within 48 hours.

The deputation was headed by Mr James Hall (Labour), M.P. for Whitechapel, and included Mr. A. M. Watt (Secretary of the London Trades Council), Father Graser, Mr. J. W. Bentley and M. J. Pearce...

Mr. Bentley said the population in East London, consisting of different races and creeds, have lived together in peace and harmony for generations until the advent of organized Fascist provocation of race against race...

The Independent Labour Party issued a leaflet yesterday calling on East London workers to take part in the counter demonstration which assembles at Aldgate at 2.p.m.

(3) The Jewish Chronicle (2nd October, 1936)

Urgent Warning. It is understood that a large Blackshirt demonstration will be held in East London on Sunday afternoon. Jews are urgently warned to keep away from the route of the Blackshirt march from their meetings. Jews who, however innocently, became involved in any possible disorders will be actively helping anti-Semitism and Jew-baiting. Unless you want to help the Jew-baiters - Keep Away.

(4) The Daily Herald (5th October 1936)

By 1.30 p.m., an hour before the scheduled time of the Fascist muster, anti-Fascists had massed in tens of thousands.

They formed a solid block at the junction of Commercial Street, Whitechapel Road and Aldgate. It was through this area that Mosley would have to reach his goal, Victoria Park, Stepney and the Socialists, Jews and Communists of the East End were determined that "Mosley should not pass!"

At the time every available policeman - about 10,000 in all - was converging on Whitechapel from all parts of London. Mounted police rode into the huge throng and forced the demonstrators back into the streets. Cordons were then flung across to keep a clear space for the marchers.

(5) The Daily Herald (5th October 1936)

Thousands of demonstrators barred the way when Sir Oswald Mosley and his Blackshirts attempted to march into the East End yesterday. Riots broke out; scores were injured in police baton charges; sixty-nine arrests were made.

The crowds were aroused by fury by the Fascists' constant Jew baiting and marches into Jewish districts, and determined that the Blackshirt assembly should not take place.

More than 100,000 anti-Fascists massed round Royal Mint Street, where the Blackshirts planned to rally. Ten thousands police formed cordons at many points to keep them back. Fighting broke out and scores of baton charges were made.

At Cable Street, Stepney, a crowd of men dragged a lorry from a builders' yard and with this as a foundations, started to build a barricade across the roadway. Lengths of timber, corrugated iron and barrels were added. In front broken glass was sprinkled to check the police horses.

(6) The Daily Worker (5th October 1936)

Sir Oswald Mosley's challenge to East London yesterday resulted in the most humiliating rout of the Blackshirts. The trumpeted march through Whitechapel never took place. Instead, the Blackshirt marchers were escorted by thousands of police from Royal Mint Street at 4 o'clock - two hours after the scheduled time of departure - away from Whitechapel, westwards not eastwards...

The rout of the Mosley gang is due entirely to the splendid way in which the whole of East London's working-class rallied as one man (and one woman); to bar the way to the Blackshirts. Jew and Gentile, docker and garment worker, railwayman and cabinet-maker, turned out in their thousands to show that they have no use for Fascism.

(7) The Jewish Chronicle (9th October, 1936)

As soon as it was announced that Sir Oswald Mosley was to lead a procession of uniformed Blackshirts through the East End of London and address open-air meetings in Limehouse, Bow, Bethnal Green and Shoreditch, it was obvious that there would be bloodshed. The Mayors of Stepney, Shoreditch, Bethnal Green, Hackney and Popular implored the Home Office to ban the demonstration. The Jewish People's Council Against Fascism and Anti-Semitism organised a petition to the same effect. It was signed by nearly 100,000 people... The Rt. Hon. George Lansbury, M.P., wrote to the Home Secretary asking him to divert the march. The Home Office gave no answer. The fight was on...

On Sunday, Fascism received the greatest blow that it has yet had in this country. For months the British Union of Fascists have been sowing the seeds of anti-Semitic hate in East London. Night after night street corner meetings have been held to stir up the Gentile population against the Jewish. Then came the announcement that the BUF would contest the London County Council Elections - on the same anti-Semitic platform.

As the crowning stroke of Fascist impudence, Sir Oswald Mosley proclaimed his intention of personality invading the East End of Sunday last, at the head of columns of his blackshirts and of marching to four open-air meetings where he would deliver speeches. The Home Office refused to interfere and thousands of police were there to ensure his safe conduct. But neither the march nor the meetings took place. They were stopped by the people of East London. Hundreds of thousands of ratepayers thronged the streets and chanted: "He shall not pass!" After many baton charges the Commissioner of Police had to admit that his task was impossible. Popular feeling was too great. He banned the march and escorted the Blackshirts home.