The New Party

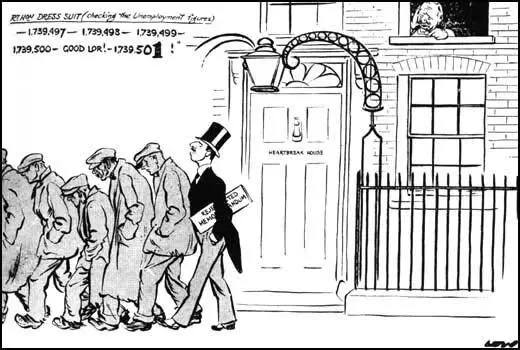

In January 1930 unemployment in Britain reached 1,533,000. By March, the figure was 1,731,000. Oswald Mosley proposed a programme that he believed would help deal with the growing problem of unemployment in Britain. According to David Marquand: "It made three main assertions - that the machinery of government should be drastically overhauled, that unemployment could be radically reduced by a public-works programme on the lines advocated by Keynes and the Liberal Party, and that long-term economic reconstruction required a mobilisation of national resources on a larger scale than has yet been contemplated. The existing administrative structure, Mosley argued, was hopelessly inadequate. What was needed was a new department, under the direct control of the prime minister, consisting of an executive committee of ministers and a secretariat of civil servants, assisted by a permanent staff of economists and an advisory council of outside experts." (1)

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, was a strong believer in laissez-faire economics and disliked the proposals. (2) MacDonald had doubts about Snowden's "hard dogmatism exposed in words and tones as hard as the ideas" but he also dismissed "all the humbug of curing unemployment by Exchequer grants." (3) MacDonald passed the Mosley Memorandum to a committee consisting of Snowden, Tom Shaw, Arthur Greenwood and Margaret Bondfield. The committee reported back on 1st May. Mosley's administrative proposals, the committee claimed "cut at the root of the individual responsibilities of Ministers, the special responsibility of the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the sphere of finance, and the collective responsibility of the Cabinet to Parliament". The Snowden Report went onto argue that state action to reduce unemployment was highly dangerous. To go further than current government policy "would be to plunge the country into ruin". (4)

Resignation of Oswald Mosley

Ramsay MacDonald recorded in his diary what happened when Mosley heard the news about his proposals being rejected. "Mosley came to see me... had to see me urgently: informed me he was to resign. I reasoned with him and got him to hold his decision over till we had further conversations. Went down to Cabinet Room late for meeting. Soon in difficulties. Mosley would get away from practical work into speculative experiments. Very bad impression. Thomas light, inconsistent but pushful and resourceful; others overwhelmed and Mosley on the verge of being offensively vain in himself." (5)

Oswald Mosley was not trusted by most of his fellow MPs. One Labour Party MP, Clement Attlee, said Mosley had a habit of speaking to his colleagues "as though he were a feudal landlord abusing tenants who are in arrears with their rent". (6) John Bew described Mosley as "handsome... lithe and black and shiny... he looked like a panther but behaved like a hyena". (7)

At a meeting of Labour MPs took place on 21st May, Oswald Mosley outlined his proposals. This included the provision of old-age pensions at sixty, the raising of the school-leaving age and an expansion in the road programme. He gained support from George Lansbury and Tom Johnson, but Arthur Henderson, speaking on behalf of MacDonald, appealed to Mosley to withdraw his motion so that his proposals could be discussed in detail at later meetings. Mosley insisted on putting his motion to the vote and was beaten by 210 to 29. (8)

Mosley now resigned from the government and was replaced by Clement Attlee. It has been claimed that MacDonald was so fed up with Mosley that he looked around him and choose the "most uninteresting, unimaginative but most reliable among his backbenchers to replace the fallen angel". Winston Churchill said Attlee was "a modest little man, with plenty to be modest about". Mosley was more generous as he accepted that he had "a clear, incisive and honest mind within the limits of his range". However, he added, in agreeing to take his job, Attlee "must be reckoned as content to join a government visibly breaking the pledges on which he was elected." (9)

The New Party

It was now clear that while Ramsay MacDonald was in power, Mosley's economic ideas would never be accepted. He therefore decided he had to have his own political party. In January 1931, Sir William Morris (later Lord Nuffield), a motor-car manufacturer, gave Mosley a cheque for £50,000 to form a new political party. Further donations came from the industrialist, Wyndham Portal, and tobacco millionaire Hugo Cunliffe-Owen. The left-wing Labour MP, Aneurin Bevan, who had supported the Mosley Memorandum, argued that if you accept funding from industrialists, "you will end up as a fascist party". (10)

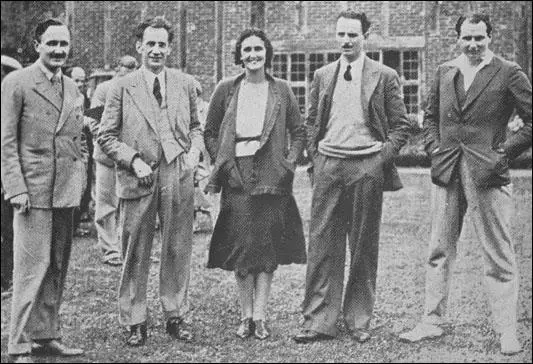

On 20th February, 1931, Mosley and five Labour Party MPs, Cynthia Mosley, John Strachey, Robert Forgan, Oliver Baldwin (the son of Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the Conservative Party) and William J. Brown, decided to resign from the party. William E. Allen, the Tory MP for West Belfast, and Cecil Dudgeon, the Liberal MP for Galloway, also agreed to join the New Party. However, Brown and Baldwin changed their minds and sat in the House of Commons as Independents and six months later rejoined the Labour Party. (11).

Other people who joined the New Party included Cyril Joad (Director of Propaganda), Harold Nicolson (editor of their journal, Action), Mary Richardson (former member of the Women's Social and Political Union), John Becket and Peter Dunsmore Howard (captain of the England national rugby union team). Other members included Allan Young and Jack Jones, both former member of the Labour Party and James Lees-Milne, an architectural historian. (12)

At a committee meeting of the New Party on 14th May 1931, Oswald Mosley urged the formation of a group young men to provide protection at political meetings from other political groups. "The Communist Party will develop a challenge in this country which will seriously alarm people here. You will in effect have the situation which arose in Italy and other countries and which summoned into existence the modern movement which now rules in those countries. We have to build and create the skeleton of an organisation so as to meet it when the time comes." (13)

These comments disturbed those on the left of the party such as John Strachey and Cyril Joad, who disliked the comparisons with the Sturmabteilung (SA) used by the Nazi Party in Germany. This information was leaked to the press and he was forced to deny the comparisons with Adolf Hitler: "We are simply organising an active force of our young men supporters to act as stewards. The only methods we shall employ will be English ones. We shall rely on the good old English fist." (14)

Cynthia Mosley also disagreed with her husband's move to the right. According to Robert Skidelsky: "Cimmie (Cynthia) was frankly terrified of where his restlessness would lead him. She hated fascism and Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere, the press baron). She threatened to put a notice in The Times dissociating herself from Mosley's fascist tendencies. They bickered constantly in public, Cimmie emotional and confused, Mosley ponderously logical and heavily sarcastic." (15)

Harold Nicolson also was worried by Mosley's attraction to fascism. "What makes it so distressing is that I should like to be able to encourage and support you in everything you do and feel.... I do not think that in practice you will succeed in keeping distinct the ideology of fascism from the violent and untruthful methods which the fascists have adopted in Italy. I think there may well be a future for the corporate state idea in this country. But I do not think... there is any possible future for direct action: we have, by training and temperament, become possessed of indirect minds." (16)

John Strachey believed that the New Party should develop close contacts with the Soviet Union: "A New Party Government will enter into close economic relations with the Russian Government and will endeavour to conclude such trading contracts between suitable British and Russian statutory organisations as will rapidly develop the controlled interchange of goods between the two countries." When this policy was rejected, Strachey resigned from the party. (17)

Election Results

The New Party's first electoral contest was at Ashton-under-Lyne after the death of Albert Bellamy, the Labour MP. Allan Young, a former member of the Labour Party, was selected as the New Party candidate. Jack Jones, a left-wing orator, was hired to make speeches for the party at £5 a week. He later recalled the important role that Cynthia Mosley played in the campaign: "Cynthia Mosley was both able and willing. With me she must have addressed at least a score of very big outdoor crowds during the campaign, and also scores of 'in our street' talks to women. Whilst others in the first flight were looking important in the presence of reporters, or talking about the holding of the floating Liberal vote, the cornering of the Catholic vote, and preparing their speeches for the well-stewarded big meetings indoors each evening, Cynthia Mosley was out getting the few votes that were got." (18)

Oswald Mosley, who had been ill with pleurisy only became involved six days before the election: "Oswald Mosley... challenges Arthur Henderson to meet him tomorrow in open debate and this stirs the audience to enthusiasm and excitement. Having thus broken the ice, he launches on an emotional oration on the lines that England is not yet dead and that it is for the New Party to save her. He is certainly an impassioned revivalist speaker, striding up and down the rather frail platform with great panther steps and gesticulating with a pointing, and occasionally a stabbing, index; with the result that there was a real enthusiasm towards the end and one had the feeling that 90% of the audience were certainly convinced at the moment." (19)

John Broadbent, the Conservative Party candidate won the election with 12,420 votes. The Labour Party came second with 11,005and Allan Younga poor third with 4,472. The main impact of the New Party was that it enabled the Conservatives to win a seat from Labour. Mosley decided to change tactics and had a meeting with David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, and suggested that they joined forces against the recently established National Government led by Ramsay MacDonald. Mosley's friend, Robert Bruce Lockhart reported "Tom (Oswald Mosley) has been seeing a good deal of Winston. He claims he will get support from Labour and Conservatives and Lloyd George." (20)

Mosley now realised that he could not be successful on the left. He told Harold Nicolson that the main support for the New Party "which is very encouraging", came from younger Conservatives and was "distinctly Fascist in character". (21) On 23rd July, 1931, John Strachey and Allan Young, resigned from the New Party because they felt that Mosley was "drifting very rapidly back to Toryism." (22) Cyril Joad also left that month "because it (the New Party) was about to subordinate intelligence to muscular bands of young men". (23)

Mosley even considered doing a deal with the National Government. On 1st October, 1931, he admitted to Nicolson that he had a secret meeting with Neville Chamberlain, and that arrangements for a secret deal to get some New Party candidates into the House of Commons. (24) These negotiations ended in failure and Mosley decided that he would be open in portraying the New Party as a Fascist organisation. Richard T. Griffiths has pointed out that the main reason he was moving towards Fascism "was because help of any kind was important, and more help was likely from the Right." (25)

During the 1931 General Election Mosley held large open-meetings all over England. James Lees-Milne, one of the New Party candidates, commented later: "He brooked no argument, would accept no advice. He had in him the stuff of which zealots are made. The posturing, the grimacing, the switching on and off of those gleaming teeth, and the overall swashbuckling... were more likely to appeal to Mayfair flappers than to sway indigent workers." (26) Mosley made it clear the the New Party had "purged the party of all associations with Socialism". (27)

The New Party fielded 25 candidates in the General Election. Cynthia Mosley refused to stand and her husband decided to make use of her personal following and stood instead of her at Stoke-on-Trent. All of its resources were concentrated in seats held by the Labour Party. Only a few weeks before the election, Mosley announced it was committed to the corporate state. Its newspaper, pointed out that though inspired by the Fascist movement it wanted British answers "framed to accord with the character and high experience of this race". It went on to argue the policies would be "within the framework of the Corporate State, we wish to give the fullest possible expansion to individual development and enjoyment". Finally it announced that it planned to form a special defence corps." (28)

The election took place on 27th October, 1931. Oswald Mosley obtained 10,500 votes in Stoke but was bottom of the poll. Only two candidates, Mosley and Sellick Davies, standing in Merthyr Tydfil, saved their deposits. The total votes cast for the New Party were 36,377. This compared badly with the Communist Party of Great Britain, which managed 74,824 votes for 26 candidates. Ramsay MacDonald, and his National Government won 556 seats. Mosley told Nicolson that "we have been swept away in a hurricane of sentiment" and that "our time is yet to come". (29)

The British Union of Fascists

In December, 1931, Harold Harmsworth, 1st Lord Rothermere, the press baron, approached Oswald and told him that he was prepared to put the Harmsworth press at his disposal if he succeeded in organising a disciplined movement from the remnants of the New Party. Harold Nicolson recorded that "Cimmie, who is profoundly working-class at heart, does not at all like this Harmsworth connection" and warned her husband that she would put a notice in The Times "to the effect that she disassociates herself from his fascist tendencies." (30)

In January 1932, Oswald Mosley, William E. Allen and Harold Nicholson visited Italy to study fascism at first hand. Mosley met Benito Mussolini who he found "affable but unimpressive". Mussolini advised Mosley to "call himself a fascist, but not to try the military stunt in England". Nicholson claimed in his diary that Mosley was not put off by the way Mussolini had arrested his opponents and the censorship of Italian newspapers. "Mosley... cannot keep his mind off shock troops, the arrest of MacDonald and J. H. Thomas, their internment in the Isle of Wight and the roll of drums around Westminster. He is a romantic. That is a great failing." (31)

On his return to England, Mosley wrote an article in The Daily Mail about the achievements of Mussolini. "A visit to Mussolini... is typical of that new atmosphere. No time is wasted in the polite banalities which have so irked the younger generation in Britain when dealing with our elder statesmen.... Questions on all relevant and practical subjects are fired with the rapidity and precision of bullets from a machine gun; straight, lucid, unaffected exposition follows of his own views on subjects of mutual interest to him and to his visitor.... The great Italian represents the first emergence of the modern man to power; it is an interesting and instructive phenomenon. Englishmen who have long suffered from statesmanship in skirts can pay him no less, and need pay him no more, tribute than to say, Here at least is a man". (32)

Mosley now became convinced that the time was right to establish a fascist party. There had been fascist groups in the past. Miss Rotha Lintorn-Orman established the British Fascisti organization in 1923. She later said: "I saw the need for an organization of disinterested patriots, composed of all classes and all Christian creeds, who would be ready to serve their country in any emergency." Members of the British Fascists had been horrified by the Russian Revolution. However, they had gained inspiration from what Mussolini had done it Italy. (33)

Most members of the British Fascisti came from the right-wing of the Conservative Party. Early recruits included William Joyce, Maxwell Knight and Nesta Webster. Knight's work as Director of Intelligence for the British Fascists brought him to the attention of Vernon Kell, Director of the Home Section of the Secret Service Bureau. This government organization had responsibility of investigating espionage, sabotage and subversion in Britain and was also known as MI5. In 1925 Kell recruited Knight to work for the Secret Service Bureau and played a significant role in helping to defeat the General Strike in 1926. (34)

Arnold Leese, a retired veterinary surgeon, had founded the Imperial Fascist League (IFL) in 1929. He had a private army called the Fascist Legions, who never numbered more than three dozen, wore black shirts and breeches. The IFL defined fascism as the "patriotic revolt against democracy and a return to statesmanship" and planned to "impose a corporate state" on the country. It also believed that Jews should be banned from citizenship. The IFL enemies were Communism, Freemasonry and Jews. (35)

Mosley originally dismissed the Imperial Fascist League as "one of those crank little societies mad about the Jews". However, on 27th April 1932, Mosley arranged for Leese to speak to New Party members, on the subject of The Blindness of British Politics under Jew Money-Power. However, the two men did not get on well together. Leese refused all co-operation with Mosley, "believing him to be in the pay of the Jews". (36)

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was formally launched on 1st October, 1932. It originally had only 32 members and included several former members of the New Party: Cynthia Mosley, Robert Forgan, William E. Allen, John Beckett and William Joyce. Mosley told them: "We ask those who join us... to be prepared to sacrifice all, but to do so for no small or unworthy ends. We ask them to dedicate their lives to building in the country a movement of the modern age... In return we can only offer them the deep belief that they are fighting that a great land may live." (37)

Primary Sources

(1) David Marquand, Ramsay MacDonald (1977)

On January 23rd, Mosley sent MacDonald a copy of a long memorandum on the economic situation, on which he had been at work for well over a month, and which has gone down to history as the "Mosley Memorandum". It made three main assertions - that the machinery of government should be drastically overhauled, that unemployment could be radically reduced by a public-works programme on the lines advocated by Keynes and the Liberal Party, and that long -term economic reconstruction required "a mobilisation of national resources on a larger scale than has yet been contemplated". The existing administrative structure, Mosley argued, was hopelessly inadequate. What was needed was a new department, under the direct control of the prime minister, consisting of an executive committee of ministers and a secretariat of civil servants, assisted by a permanent staff of economists and an advisory council of outside experts. The problems of substance, he went on, had to be looked at under two quite separate headings, which had so far been muddled up. First, there was the long-term problem of economic reconstruction, which could be solved only by systematic Government planning, designed to create new industries as well as to revitalize old ones. Second, there was the immediate problem of unemployment. This could be solved by making road-building a national responsibility, by raising a loan of £200 million and spending it on roads and other public works over the next three years, by raising the school-leaving age and by introducing earlier retirement pensions. Whatever their faults, Mosley concluded flamboyantly, his proposals "at least represent a coherent and comprehensive conception of national policy... It is for those who object to show either that present policy is effective for its purpose, or to present a reasoned alternative which offers a greater prospect of success.

(2) Ramsay MacDonald, diary entry (19th May, 1930)

Mosley came to see me... had to see me urgently: informed me he was to resign. I reasoned with him and got him to hold his decision over till we had further conversations. Went down to Cabinet Room late for meeting. Soon in difficulties. Mosley would get away from practical work into speculative experiments. Very bad impression. Thomas light, inconsistent but pushful and resourceful; others overwhelmed and Mosley on the verge of being offensively vain in himself.

(3) Richard T. Griffiths, Fellow Travellers of the Right: British Enthusiasts for Nazi Germany 1933-39 (1980)

Towards the end of 1930, disillusioned by his lack of success at the Party Conference, he (Oswald Mosley) began to think in terms of "a new party of younger Nationalists" though he was uncertain about when to launch it, particularly because of lack of money and of press support. When the possibility of the future Lord Nuffield providing financial support came up, he decided to "launch his manifesto practically creating the National Party". After Morris had produced £50,000 in January 1931, the die was cast, and in February Mosley and five supporters (including his wife) left the Parliamentary Labour Party. The New Party was launched on 1st March.

It must be stressed that this party, and Mosley's own future, were conceived in parliamentary terms. The six parliamentary members still had their seats, and the party proceeded to contest a by-election at Ashton-under-Lyne as early as April. Though the result was disappointing, the New Party candidate saved his deposit. Mosley became involved in various discussions with major political figures. On 21 July he, Lloyd George and Winston Churchill met at a specially organised private dinner party, at which the prospect of together forming a National Opposition in the event of a coalition between Baldwin and MacDonald was mooted. A month later, two days after the formation of the National Government, Mosley privately expressed himself delighted with the prospects. The Labour Party were a rump "without a single man of any eminence"...

Meanwhile, various changes had been happening within the movement. It was veering to the Right; and one finds it hard to avoid coming to the conclusion that this was because help of any kind was important, and more help was likely from the Right. In February, Mosley had been convinced that his "young men's party", though it would break across party lines, "could only come through the Labour Party. Certainly, the young men in the Conservative Party are "dead". By May he found that. the main response to the New Party, "which is very encouraging", came from the younger Conservative group, and was "distinctly Fascist in character". The negotiations with Churchill showed the way he was now moving, a way in which some of his earliest adherents refused to follow him. On 23 July John Strachey and Allan Young resigned, because they felt that Mosley was "drifting very rapidly back to Toryism" and was "acquiring a Tory mind".

Another development was the Youth Movement (originally started in order to steward the party meetings, which were becoming subject to rowdy opposition), and the movement's growing interest in Fascism. By May, people had become aware of Mosley's use of violent methods. There was talk of "fisticuffers": and it became evident that there were two distinct elements in the party - the intellectuals like Sacheverell Sitwell, and the toughs like the boxer "Kid Lewis." In July Dr Joad left the party "because he felt it was about to subordinate intelligence to muscular bands of young men."

(4) Nicholas Mosley, Rules of the Game: Sir Oswald and Lady Cynthia Mosley 1896-1933 (1982)

Harold Nicolson was a newcomer to politics. He had just resigned from the diplomatic service and was working as a journalist on the Evening Standard. He had been attracted to the New Party, he said, out of (1) Personal affection and belief in Tom (Oswald Mosley): (2) A conviction that a serious crisis was impending and that our economic and parliamentary system must be transformed if collapse were to be avoided." He got carried along by the sense that Tom engendered of being in touch with great events; also by the sense of fun.

Another leading figure in the New Party was Peter Howard, captain of the England Rugby Football team. Harold Nicolson wrote to Cimmie "Peter Howard I have a feeling is bowled over by your charms - but so are we all". Peter Howard had organised a group of young men from Oxford to protect New Party meetings: these were referred to in the press as "Mosley's Biff Boys" or "strapping young men in plus fours". The emphasis of the New Party was on youth: a journalist wrote of the party headquarters at Ashton-under-Lyne - "Young men with fine foreheads and an expression of faith dash from room to room carrying proof-sheets and manifestos: I have seldom seen so many young people so excited and so pleased".

When the election results were announced the Conservatives had got 12,420 votes, Labour 11,005, and Allan Young of the New Party 4,472 - just saving his deposit. This result was not discreditable to a party only two months old but it was not as good as Tom had hoped: he found, as he was so often to find later, that the enthusiasm he engendered as a one-man-band did not effectively last until his audience went to the poll. But it had lasted long enough, Labour supporters imagined, for the intervention of the New Party to have ensured that the Conservatives won what had previously been held to be a safe Labour seat. In fact, the New Party's intervention had probably somewhat lessened what was a general swing against Labour throughout the country. But political crowds want scapegoats, not analysis...