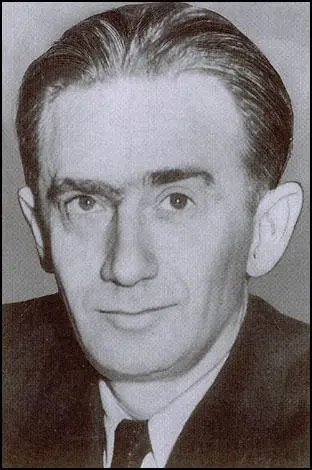

Antonina Porfirieva

Antonina Porfirieva was born in Russia in 1902. Her father was Semyon Porfiriev, worked at the Putilov factory in St Petersburg. Her mother was from Finland. She joined military intelligence and in 1925 worked for the Fourth Department at the Soviet embassy in Vienna. At the time she was described as being "tall, fair and strikingly blond".

While in Austria she met Walter Krivitsky, a Soviet secret agent. They married on 15th May 1926. Krivitsky served all over Europe and had difficulty obtaining permission for his wife to go with him. Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "intelligence work, and indeed private life, would be complicated for the Krivitsky by the fact that she was legal and he was illegal. During the first years of their marriage, they were forced to live separately when abroad, Walter in hotels and Tonia near the embassy in Vienna, each with a cover spouse who also worked for military intelligence. They had to avoid being seen together. Their conjugal conjugations were clandestine."

Rotterdam

In July 1933 Walter Krivitsky was transferred to Rotterdam as director of intelligence with liaison responsibilities for other European countries. According to Krivitsky he was now "Chief of the Soviet Military Intelligence for Western Europe". This time he was able to travel and live with his wife. By this stage the NKVD had realised that marriage makes a good cover for illicit activities. The couple moved to a townhouse at 32 Celebesstraat, The Hague. Krivitsky took the identity of Dr. Martin Lessner, who sold art books.

Krivitsky's main objective was to build spy networks in Europe. His agents organized groups of dedicated Communists prepared to assist the Soviet Union if war broke out. The plan was for these units to disrupt communications, wreck machinery and blow up munitions depots. Krivitsky also recruited journalists, politicians, artists and government officials. Some he paid with money, others were willing to work for free as they believed in communism. Probably his most important agent was Pierre Cot, the Air Minister, in the government of Léon Blum.

Krivitsky later claimed that Military Intelligence never stole classified documents outright, but borrowed them long enough to photograph them and then returned them to their original places. All its officers and most of its agents were trained in the use of a Lecia camera. According to Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004): "For remote locations, they used a little suitcase containing all the necessary equipment. Krivitsky wrote his reports by hand, photographed them and sent the undeveloped film to Moscow through the embassy. The rolls of film containing the purloined material went the same way. The service had mailing canisters for film that would self-destruct if opened improperly, but these were used only in emergency or war situations."

Purge of NKVD Agents

Meanwhile, back in the Soviet Union, Nikolai Yezhov established a new section of the NKVD named the Administration of Special Tasks (AST). It contained about 300 of his own trusted men from the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Yezhov's intention was complete control of the NKVD by using men who could be expected to carry out sensitive assignments without any reservations. The new AST operatives would have no allegiance to any members of the old NKVD and would therefore have no reason not to carry out an assignment against any of one of them. The AST was used to remove all those who had knowledge of the conspiracy to destroy Stalin's rivals. One of the first to be arrested was Genrikh Yagoda, the former head of the NKVD.

Within the administration of the ADT, a clandestine unit called the Mobile Group had been created to deal with the ever increasing problem of possible NKVD defectors, as officers serving abroad were beginning to see that the arrest of people like Yagoda, their former chief, would mean that they might be next in line. The head of the Mobile Group was Mikhail Shpiegelglass. By the summer of 1937, over forty intelligence agents serving abroad were summoned back to the Soviet Union.

Walter Krivitsky realised that his life was in danger. Alexander Orlov, who was based in Spain, had a meeting with fellow NKVD officer, Theodore Maly, in Paris, who had just been recalled to the Soviet Union. He explained his concern as he had heard stories of other senior NKVD officers who had been recalled and then seemed to have disappeared. He feared being executed but after discussing the matter he decided to return and take up this offer of a post in the Foreign Department in Moscow. General Yan Berzin and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, were also recalled. Maly, Antonov-Ovseenko and Berzen were all executed.

Krivitsky's old friend, Ignaz Reiss, was beginning to have great doubts about the truth of the Show Trials. His wife, Elsa Poretsky, had visited Moscow in early 1937. She noted that: "The Soviet citizen does not rejoice in the splendor, he does not marvel at the blood trials, he hunches down deeper, hoping only perhaps to escape ruin. Before every Party member the dread of the purge. Over every Party member and non-Party member the lash of Stalin. Lack of initiative it's called, then lack of vigilance - counter-revolution, sabotage, Trotskyism. Terrified to death, the Soviet man hastens to sign resolutions. He swallows everything, says yea to everything. He has become a clod. He knows no sympathy, no solidarity. He knows only fear."

Ignaz Reiss met with Krivitsky and suggested that they should both defect in protest as a united demonstration against the purge of leading Bolsheviks. Krivitsky rejected the idea. He suggested that the Spanish Civil War would probably revive the old revolutionary spirit, empower the Comintern and ultimately drive Stalin from power. Krivitsky also made the point that that there was no one to whom they could turn. Going over to Western intelligence services would betray their ideals, while approaching Leon Trotsky and his group would only confirm Soviet propaganda, and besides, the Trotskists would probably not trust them.

Walter Krivitsky was recalled to Moscow. He later recalled that he took the opportunity to "find out at firsthand what was going on in the Soviet Union". Krivitsky wrote that Joseph Stalin had lost the support of most of the Soviet Union: "Not only the immense mass of the peasants, but the majority of the army, including its best generals, a majority of the commissars, 90 percent of the directors of factories, 90 percent of the Party machine, were in more or less extreme degree opposed to Stalin's dictatorship."

Death of Ignaz Reiss

In July 1937 Ignaz Reiss was warned that if he did not go back to Moscow at once he would be "treated as a traitor and punished accordingly". Reiss responded by sending a letter to the Soviet Embassy in Paris explaining his decision to break with the Soviet Union because he no longer supported the views of Stalin's counter-revolution and wanted to return to the freedom and teachings of Lenin. "Up to this moment I marched alongside you. Now I will not take another step. Our paths diverge! He who now keeps quiet becomes Stalin's accomplice, betrays the working class, betrays socialism. I have been fighting for socialism since my twentieth year. Now on the threshold of my fortieth I do not want to live off the favours of a Yezhov. I have sixteen years of illegal work behind me. That is not little, but I have enough strength left to begin everything all over again to save socialism. ... No, I cannot stand it any longer. I take my freedom of action. I return to Lenin, to his doctrine, to his acts."

According to Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001): "On learning that Reiss had disobeyed the order to return and intended to defect, an enraged Stalin ordered that an example be made of his case so as to warn other KGB officers against taking steps in the same direction. Stalin reasoned that any betrayal by KGB officers would not only expose the entire operation, but would succeed in placing the most dangerous secrets of the KGB's spy networks in the hands of the enemy's intelligence services. Stalin ordered Yezhov to dispatch a Mobile Group to find and assassinate Reiss and his family in a manner that would be sure to send an unmistakable message to any KGB officer considering Reiss's route."

Reiss was found hiding in a village near Lausanne, Switzerland. It was claimed by Alexander Orlov that a trusted Reiss family friend, Gertrude Schildback, lured Reiss to a rendezvous, where the Mobile Group killed Reiss with machine-gun fire on the evening of 4th September 1937. Schildback was arrested by the local police and at the hotel was a box of chocolates containing strychnine. It is believed these were intended for Reiss's wife and daughter.

Defection

After the death of Ignaz Reiss, Krivitsky decided to defect. Walter Krivitsky and Antonina managed to escape to Canada where he lived under the cover name of Walter Thomas. Krivitsky eventually contacted the FBI and gave details of 61 agents working in Britain. Krivitsky also provided an insight into Stalin's thinking. John V. Fleming, the author of The Anti-Communist Manifestos: Four Books that Shaped the Cold War (2009): "Krivitsky was sufficiently privy to the thinking within the Kremlin to be able to predict to his absolutely unbelieving auditors that Stalin was more interested in finding an accommodation with Hitler than in countering him in Spain or elsewhere.... Then, in late August, the Germans and the Russians jointly announced the pact that Krivitsky had predicted."

In 1940 Krivitsky was brought to London to be interviewed by Dick White and Guy Liddell of MI5. Krivitsky did not know the names of these agents but described one as being a journalist who had worked for a British newspaper during the Spanish Civil War. Another was described as "a Scotsman of good family, educated at Eton and Oxford, and an idealist who worked for the Russians without payment." These descriptions fitted Kim Philby and Donald Maclean. However, White and Liddle were not convinced by Krivitsky's testimony and his leads were not followed up.

Later that year Walter Krivitsky moved to New York City where he collaborated with the journalist, Isaac Don Levine, for a series of articles in the Saturday Evening Post, exposing what was going on in the Soviet Union. One night, Krivitsky met Whittaker Chambers. He recorded the meeting in his book, Witness (1952): "But one night, when I was at Levine's apartment in New York, Krivitsky telephoned that he was coming over. There presently walked into the room a tidy little man about five feet six with a somewhat lined gray face out of which peered pale blue eyes. They were professionally distrustful eyes, but oddly appealing and wistful, like a child whom life has forced to find out about the world, but who has never made his peace with it. By way of handshake, Krivitsky touched my hand. Then he sat down at the far end of the couch on which I also was sitting. His feet barely reached the floor."

Krivitsky said that he turned against communism after the Kronstadt Uprising: "Krivitsky meant that by the decision to destroy the Kronstadt sailors, and by its cold-blooded action in doing so, Communism had made the choice that changed it from benevolent socialism to malignant fascism. Today, I could not answer, yes, to Krivitsky's challenge. The fascist character of Communism was inherent in it from the beginning. Kronstadt changed the fate of millions of Russians. It changed nothing about Communism. It merely disclosed its character."

I Was Stalin's Agent

In 1939, Walter Krivitsky, with the help of Isaac Don Levine, published I Was Stalin's Agent. One of the most powerful sections of the book was an account of Stalin's involvement in the Spanish Civil War. "Stalin's intervention in Spain had one primary aim... namely, to include Spain in the sphere of the Kremlin's influence... The world believed that Stalin's actions were in some way connected with world revolution. But this is not true. The problem of world revolution had long before that ceased to be real to Stalin... He was also moved however, by the need of some answer to the foreign friends of the Soviet Union who would be disaffected by the great purge. His failure to defend the Spanish Republic, combined with the shock of the great purge, might have lost him their support." Krivitsky also appeared before Martin Dies and the Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in October, 1939.

Visit to Barboursville

On Thursday 6th February, 1941, Krivitsky visited Eitel Wolf Dobert on his 90-acre farm in Barboursville, about 15 miles north of Charlottesville. The Doberts moved into a two-room log cabin and decided to raise chickens. Margarita later recalled: "My God, it was hard! We nearly starved. When we made $50 a month it was a great month." Krivitsky told Dobert he planned to buy a farm in Virginia.

Soon after arriving Krivitsky purchased a .38 caliber Colt automatic pistol and cartridges at the Charlottesville Hardware store. On his return to the farm he and Dobert began target practice. By 8th February he had run out of ammunition. Margarita Dobert later commented: "On Saturday he asked me to drive to town and buy 150 cartridges for the gun."

Death at the Bellevue Hotel

On Sunday 9th February, Walter Krivitsky checked into the Bellevue Hotel in Washington at 5:49 p.m. He paid $2.50 in advance for the room and signed his name in the register as Walter Poref. The desk clerk, Joseph Donnelly, described him afterwards as nervous and trembling. At 6:30, he called down for a bottle of Vichy sparkling water. The bellboy considered him a typical foreigner - "quiet and solemn".

The young maid, Thelma Jackson, knocked on Krivitsky's room at 9.30. When she did not receive an answer she assumed the room was free for cleaning and inserted her passkey. She opened the door and discovered a man lying on the bed the wrong way round, with his head toward the foot. She noticed he had "blood all over his head". The police were called and Sergeant Dewey Guest diagnosed the case as an obvious suicide. Coroner MacDonald issued a certificate of suicide that afternoon.

Krivitsky left behind three suicide notes, each one in a different language known to him (English, German and Russian). Police handwriting expert, Ira Gullickson, was shown the notes found with the body and declared that they were without any question written by the man who signed the hotel register. Gullickson argued that the notes were written on different times, because they showed an increase in nervous tension.

The first letter, in English, was addressed to Louis Waldman: "Dear Mr. Waldman: My wife and my boy will need your help. Please do for them what you can. I went to Virginia because that there I can get a gun. If my friends should have trouble please Mr. Waldman help them, they are good people and they didn't know why I bought the gun. Many thanks."

The second suicide note, in German, was addressed to Suzanne La Follette: "Dear Suzanne: I believe you that you are good, and I am dying with the hope that you will help Tonia and my poor boy. You were a good friend." This letter raised several issues. It is true that in the early days of their relationship he did write in German because his English was poor. However, in recent letters, he had used English.

The third letter was to Antonina Porfirieva: "Dear Tonia and dear Alek. Very difficult and very much want to live but I can't live any longer. I love you my only ones. It's difficult for me to write but think about me and you will understand that I have to go. Don't tell Alek yet where his father has gone. I believe that in time you will explain since it will be good for him. Forgive difficult to write. Take care of him and be a good mother - as always be strong and never get angry at him. He is after all such a such a good and such a poor boy. Good people will help you but not enemies of the Soviet people. Great are my sins I think. I see you Tonia and Alek and embrace you."

Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004) claims that two sentences in this letter cause certain problems: "Good people will help you but not enemies of the Soviet people. Great are my sins I think." He goes on to argue: "These two statements have the look of a political recantation and, as such, suggest either a mental breakdown or something dictated by the NKVD."

On hearing of Krivitsky's death, his lawyer, Louis Waldman, called a press conference and announced that he had been murdered by the NKVD and named the killer as Hans Brusse. (1) An NKVD agent (Hans Brusse) who had twice before tried to trap Krivitsky had appeared in New York City, where Krivitsky lived. (2) Krivitsky planned to buy a farm in Virginia, thus he intended to live. He had changed his name, applied for citizenship, bought a car. (3) The NKVD was expert in forgery and had samples of Krivitsky's hand in every language.

At the White House, Adolf Berle, President Roosevelt's advisor on national security wrote in his diary: "General Krivitsky was murdered in Washington today. This is an OGPU job. It means that the murder squad which operated so handily in Paris and in Berlin is now operating in New York and Washington." Joseph Brown Matthews, who was an investigator for the House Committee on Un-American Activities, commented: "It's murder. I have no doubt of it." New York Times reported that Krivitsky had told them: "If they ever try to prove that I took my own life, don't believe them."

One of the most surprising aspects of the case was that rooms on both sides of Krivitsky had been occupied. So had the rooms across the hall. In the past, guests had often complained about noises in the room next to them because of the thinness of the walls. However, no one heard gunfire in the quiet early morning hours when the suicide had taken place. The gun found in Krivitsky's room did not have a silencer.

The Washington Post argued: "All in all, it would seem that the Washington police and coroner disposed of the case in rather summary fashion... The whole thing looks like a pretty careless piece of work." Frank Waldrop of The Washington Times-Herald ridiculed the police investigation: "Anybody'd rather be a second-guessing citizen than Chief of Police Ernest W. Brown, with such a staff of lunkheads to do the field work in homicide matters." However The Daily Worker disagreed: "The capitalist press is desperately trying to make a frame-up murder case out of what is clearly established in the suicide of General Walter Krivitsky."

Alexander Kerensky believed Hans Brusse had murdered Krivitsky: "Hans Brusse is the man. The most vicious murderer in all the Soviet. We know him. We know his methods. His favourite tactic is to drive a man to suicide by threatening to capture and torture his family. It has been done many times in many countries. I believe Krivitsky got a concrete warning recently that they would kill him or kidnap his family. That is their favourite plan of operation. Krivitsky had a burning mission to expose Stalin for what he is. And in my opinion he was not the type to commit suicide."

Whittaker Chambers definitely believed that he had been killed by the NKVD: "He had left a letter in which he gave his wife and children the unlikely advice that the Soviet Government and people were their best friends. Previously he had warned them that, if he were found dead, never under any circumstances to believe that he had committed suicide." Krivitsky once told Chambers: "Any fool can commit a murder, but it takes an artist to commit a good natural death." Martin Dies, Isaac Don Levine and Suzanne La Follette all believed Krivitsky was murdered.

However, Eitel Wolf Dobert, told reporters that Krivitsky seemed very worried and probably had committed suicide. He also thought that Krivitsky had written his suicide notes the last night that he stayed on his farm. Mark Zborowski, who was later exposed as a NKVD agent who had been involved in the death of Lev Sedov, also believed Krivitsky committed suicide. He told David Dallin: "He was a neurasthenic and a paranoiac, eternally in fear of assassination. He felt that he was a traitor. As a Communist, he did not have the right to do what he was doig. He had days of high spirits and days of dejection."

Paul Wohl also disagreed he had been murdered. He said: "When we lived together, he often talked of suicide." Wohl also dismissed the idea that Hans Brusse killed Krivitsky. He claimed that although he was a Soviet agent he was not the type "to be assigned to assassinations, but rather a technician". Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004) has pointed out: "If Hans were so innocuous, one has to wonder, then why had Wohl sent his letter of warning to Krivitsky in the first place... And if he were not an assassin, but a technician, then what was he doing in America on a political assignment? And how did Wohl, a private citizen, know about any of these things?"

Jan Valtin, a former NKVD agent also took the view that Krivitsky was murdered. He said the NKVD liquidated people on foreign soil for three main reasons: "(1) To silence someone with secrets who might talk, has talked or will go on talking. (2) To eliminate someone who could be an asset to foreign intelligence services. (3) To wreak vengeance on someone who tried to break away from the Soviet Secret Service and thus to demonstrate an ability to prosecute defectors anywhere in the world, with the consequent chilling effect on potential defectors still in the service."

Another former agent, Hede Gumperz, also explained how they would have arranged his death. "The only possible lever they could have tried to use against him was his family - threatening to kill his wife and son, and promising to spare their lives only if he took his. But Krivitsky would have known with absolute certainty that, even if the threats were serious, the promises were not. After all, he himself, as a senior officer in the same service, had seen so many promises of clemency which had been made in the name of Stalin cynically broken the moment their aim was achieved."

Antonina Porfirieva believed it was a forced suicide. The main clue came from his letter: "Very difficult and very much want to live but I can't live any longer. I love you my only ones. It's difficult for me to write but think about me and you will understand that I have to go." Antonina, who had worked for the NKVD and knew about the methods they used: "I am convinced that my husband was forced to write the notes he left behind... Walter had utter contempt for suicide and would have never killed himself willingly. They forced him to write those notes and then they forced him to kill himself. He made a deal with them to save me and our boy."

Louis Waldman campaigned for the FBI to treat the case as murder. "The issue is much deeper than the discovery of whether the general's death was the result of murder or suicide... When one considers that General Krivitsky was a witness, giving valuable information as to foreign espionage in our own country to a legislative committee, to the State Department, and to the FBI itself, then in my opinion, there is the clear duty of the FBI to track down those malevolent forces which were responsible for his death."

Waldman told the FBI that he had evidence that Hans Brusse was the killer. When the FBI reopen the case he went to the press with his evidence. Recently released documents show that in March 1941 a certain Lee Y. Chertok, a Russian living in the United States, claimed to have information on the killers of Krivitsky. J. Edgar Hoover sent a memo telling the FBI not to follow up this evidence: "The Bureau is not interested in determining whether Krivitsky was murdered or whether he committed suicide."

Antonina Thomas

After the death of her husband Antonina changed her name from Krivitsky to Thomas. She found a job at the Revere Apron factory. She and her son, Alek, lived in a small two-room apartment in New York City near the American Museum of Natural History. Alek delivered flowers after school to help the family income. Alek attended Columbia University but died of a brain tumor while in his thirties.

Antonina Thomas died at the Victoria Home for the Aged in Ossining, in February 1996.

Primary Sources

(1) Edward P. Gazur, Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001)

The other defector of note was Walter Krivitsky, who at the time of Reiss's demise had been the KGB illegal rezident in Holland. His defection would reach the highest levels of the French and Soviet Governments and almost became an international incident. Krivitsky had only been with the KGB since 1935, having previously worked for the Intelligence Administration of the Red Army. He was aware of Reiss's plan to defect and attempted to warn Reiss at his hideout in Switzerland when he learned that Shpiegelglass's Mobile Group had located him. Krivitsky was to learn of Reiss's fate on the morning of 5 September, when he read in a Paris newspaper the details of a macabre murder that had been discovered near Lausanne. The given name of the murder victim was Reiss's pseudonym. Krivitsky soon learned that he had been recalled to Moscow and, being well aware of what had happened to his friend, made the decision to defect. Stalling for more time, he acted as if he were complying with the order while actually planning his escape. On the day of his scheduled departure for Moscow, Krivitsky telephoned his secretary at the Embassy to relay the message to his superiors that he was breaking with the Soviet Government. Krivitsky, his wife and son went to the southern reaches of France, where they had a temporary sanctuary.

On learning what had transpired, Yezhov immediately dispatched a Mobile Group to France with orders to kill Krivitsky and his family. French intelligence soon learned of the plan and placed Krivitsky and his family under the protective custody of the French police. What saved Krivitsky's life for the time being and placed him under the protection of the French Government was an incident of international proportions that had occurred less than a month before in Paris.

General Yevgeny Miller, head of the anti-Soviet emigre organisation in France known as the Military Union of Former Tsarist Officers, was kidnapped off the streets of Paris in broad daylight on 23 September by agents of the Soviet Government.The affair provoked an uproar and scandal in France as to how such a prominent person could be snatched in such a manner. The French police mounted one of the most intensive manhunts in their history but never succeeded in finding the perpetrators or the victim. Not wanting another debacle such as the Miller affair, the French Government summoned the Soviet Charge d'Affaires to the French Foreign Office, where he was told to convey the message to Moscow that another kidnapping on French soil would force the French Government to break diplomatic relations with the Soviet Government.

Stalin was furious at the actions of the French Government but was not in a position to provoke it with yet another incident. He would bide his time for the right opportunity. In the meantime, Krivitsky had a breathing space from the hot pursuit of the KGB and, during December 1938, would make good his escape to the United States, where he felt that he would be safe. While in the US, he provided the US Government with some intelligence. The end did come for Krivitsky for on 10 February 1941 his body was found lying in a pool of blood on the floor of his room at the Bellevue Hotel in Washington DC. He had been shot through the right temple with a .38 calibre weapon, which was found next to the body; however, no fingerprints were found as the gun had been wiped clean. There were three suicide notes, the nature of which seemed questionable. To some the death was a suicide, but to those who knew him and the ways of the Soviet secret police, the facts were evident and the murder was placed at the feet of the KGB. Orlov would read of the murder in the newspapers, and there was never any doubt in his mind as to the identity and motive of the perpetrators.

Orlov also knew that time was on the side of the KGB, as was evident in the Krivitsky case, but more so as reflected in the case of Georgi Agabekov. Agabekov had been the KGB rezident in Turkey when he broke with the Soviet Government in 1929. The KGB kept up its pursuit of him for nine long years until he was tracked down in Belgium and murdered in early 1938. This was one lesson Orlov never forgot and was certainly on his mind when he defected.

By the beginning of 1938, most of the KGB officers serving abroad who had been targeted for elimination had already returned to Moscow. Stalin and Yezhov no longer had to play out the charade that the Foreign Department was not subject to the purges in order to placate the fears of those serving abroad. Therefore, they no longer needed to keep Abram Slutsky as Chief of the Foreign Department in order to maintain this deception.