Theresa Garnett

Frances Theresa Garnett, the third child of Joshua Garnett (1862-1945), and his wife, Frances Theresa, née Armstead (1862-1888), was born at the family home in Stanningley Road, Armley, Leeds, on Thursday, 17th May 1888. (1)

Her father was a former stoker in a steam-powered woollen mill, but later found employment as an “iron planer” at the Leeds Forge Company, a metal factory that manufactured iron and steel items for the railway industry. Her mother, before her marriage was employed as a "worsted Knotter". (2)

A few weeks after the birth of her daughter Mrs Frances Garnett, became ill, complaining that she "did not feel well in her head". Mrs Garnett started to talk in "a rambling manner" and was "very much excited". Her doctor eventually suggested that she "should be removed to the Asylum." Mrs Garnett arrived at the West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum on Monday, 11th June 1888, at 12.15 pm. Fanny Garnett received some attention from the asylum’s medical officer, but she slipped into a coma and died at 8.50 pm that same day. (3)

According to Elizabeth Crawford, Theresa Garnett was educated at a convent school and later became a teacher. (4) After hearing Adela Pankhurst speak she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). On 27th April 1909 she was one of five suffragettes, who chained themselves to the bronze statues of four famous parliamentarians in the Central Lobby of the House of Commons, as a protest against a new law that penalized anyone found guilty of disorderly conduct within the confines of the Palace of Westminster while parliament was in session. (5)

On 27th June 1909 Garnett, Mary Allen and Lillian Dove-Wilcox, was arrested during a demonstration outside the Houses of Parliament that resulted in her throwing stones in Whitehall. In court Garnett stated: "I went no further than the Government have made us go, and we shall not go any further than they make us; they are responsible for all that is being done." (6)

Theresa Garnett and Hunger Strikes

Theresa Garnett was sentenced to a month in Holloway Prison. Garnett immediately went on hunger-strike. She was then accused of biting and kicking a wardress. She denied the biting charge but admitted pushing the wardress out of her cell. "The magistrate, however, believed her story, which was that I had struck her and injured her, and for this I was sent to prison for a month in the third condition." (7)

Theresa Garnett again went on hunger-strike. (8) "From the onset I determined to refuse all food… When I did this three weeks ago during my previous imprisonment, I did not feel any serious pain until the fourth day, but on this occasion, I was so weak that I felt terribly hungry all the time, and on several occasions went into a faint. I also had severe headache during the whole time... The doctor came to me one day and tried to get me to take food, asking me how many votes I thought it was worth if I lost my health for the rest of my life... And the end came sooner than I feared it might: I had been faint several times during the three days, and on Saturday afternoon the doctor came and announced to me that I was to be released." (9)

Garnett continued to take part in militant activity and on 20th August 1909 she took part with Mary Leigh, Bertha Brewster and Rona Robinson, in a demonstration on the roof of the Sun Hall in Liverpool. The local newspaper, The Liverpool Courier reported that the women "threw bricks and stones through the windows of the Sun Hall with a dexterity which was nothing short of marvellous". (10)

After more windows were smashed the police found a window cleaner to get the women down but his ladder was too short and the fire brigade were called. Eventually they managed to bring down the seven women off the roof "in a perilous descent." (11) The women were arrested and charged with wilful damage and imprisoned in Walton Prison, but after going on hunger-strike they were released later that month "owing to their emaciated condition." (12)

Winston Churchill

As a senior member of the Liberal Party government Winston Churchill became a target for the Women's Social & Political Union. Churchill had been a long-term opponent of votes for women. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public. (13)

In public he supported the principle of women's suffrage as it was party policy. In private he was totally opposed as he thought it would be to the disadvantage of the Liberal Party. Should women be given the vote on the same limited basis as men (which would favour the Conservative Party) or should there be a massive extension of the franchise to enable all adults to vote (which would favour the Labour Party). Churchill warned the Cabinet that if the government introduced plans for women's suffrage he would probably have to resign. (14)

Catherine Corbett, Adela Pankhurst, Maud Joachim and Helen Archdale decided to disrupt Churchill's public meeting at Kinnaird Hall in Dundee. Pankhurst and two men, Owen Clark and William Carr, hid themselves in an attic and threw stones, bricks and slates at the roof-light of the hall, calling out "votes for women". Meanwhile, Corbett, Joachim and Archdale, led a group of supporters that charged the barricades thrown up around the hall. (15)

The Dundee Courier reported: "Their sudden appearance (Catherine Corbett, Maud Joachim and Helen Archdale) had a magical effect on the mob. Surging round the women, they threw themselves against the solid wall of police. The officers fought valiantly, but were utterly helpless to stem the great human tide… Meanwhile the crowd time and again charged the police, and succeeded in reaching the barricades… The crowd in Reform Street were now incensed to fever pitch, and several ugly rushes were made to force a way to Bank Street." (16)

The women were arrested but Corbett later paid tribute to the courage of the Dundonians who had rioted for three hours: "they would not stop until they got the barricades down, they were glorious." (17) Each woman made a lengthy speech in court and was sentenced to ten days in prison. They all went on hunger-strike. Churchill disagreed and told the local newspaper that the women were "a band of silly, neurotic women". (18)

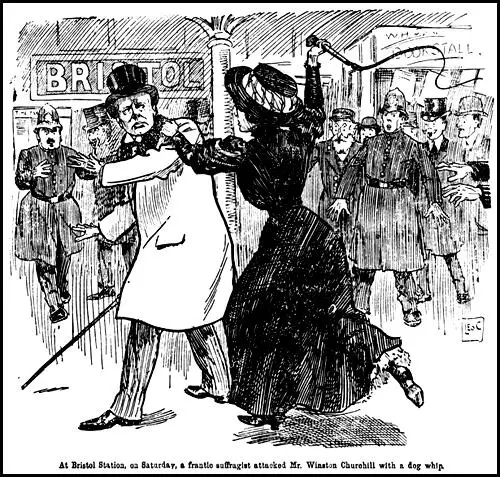

Whipping in Bristol

On 13th November 1909, Theresa Garnett accosted Winston Churchill with a horse whip in Bristol. She shouted "You brute, I will show you what English women can do." She later said had given Mr Churchill the punishment he deserved as representative of this country and unjust Government. "I am proud," she declared, "of being a woman who has had the great privilege of resenting the intolerable wrong and injustice done to my sex by these Liberal politicians, who are hypocritically denouncing the House of Lords while keeping their countrywomen in political subjection." (19)

According to Votes for Women: "Miss Garnett had determined to take vigorous action, and to humiliate Mr Winston Churchill on his arrival by the GWR. Through the magistrate subsequently in court said it was a hysterical act, it was a piece of cool daring such as has not often been witnessed. Although hemmed in by detectives, who made a semi-circle round the Minister, Miss Garnett rushed right through them with her riding-switch concealed up the sleeve of her coat. Mr Churchill alone saw her coming, and stood fascinated and petrified; he raised his arm up as she approached and thus broke the force of the first blow; she, however, got in a second, and a third." (20)

In an interview she gave many years later Garnett admitted she missed him but did "knock his hat about". She was arrested for assault but was found guilty of disturbing the peace and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Horfield Prison. (21) Her friend, Mary Blathwayt, wrote in her diary on 15th November: "Miss Garnett got one month for whipping Mr. Churchill across the face and not hurting him. I bought fruit and sent it to the prisoners before they were taken away." (22) The Magistrates bound her over, failing sureties a month's imprisonment. She refused to be bound over, expressing the hope that she would do her business better next time, and she was committed for a month. (23)

The following day, her mother, Emily Blathwayt, wrote: The papers were full of Saint Theresa as we call her." Emily went onto say that the movement was "not altogether displeased" that the newspapers had headlines that were not true such as "Winston whipped" and "Churchill flogged". Emily added that her husband Colonel Linley Blathwayt had "sent her photo which he had taken by Mary who gave it to her before she went off to prison." (24)

Theresa Garnett went on hunger-strike while in Horfield Prison. This time, instead of being released, she was forcibly fed. As a protest against this treatment, she set fire to her cell and was then placed in solitary confinement for 11 of the 15 remaining days of her sentence. After being found unconscious, she spent the rest of her sentence in a hospital ward. (25)

In March 1910 Theresa Garnett, alongside Constance Lytton, Elsie Howey, Edith Rigby, Beth Hesmondhalgh and Selina Martin were presented with "For Valour" medals. Those women who had already been awarded medals were presented with silver bars engraved with the dates of their latest force-feeding to be added to their medal ribbons. (26)

In 1910 Garnett became WSPU organizer in Camberwell. However, she disagreed with the WSPU arson campaign and left the movement. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) she "did not join any other suffrage group, although she obviously kept in touch with her erstwhile comrades." (27)

When the 1911 Census was taken, Frances Theresa Garnett, now aged 22, was recorded as a "Hospital Nurse in Training" at Harley College, Tredegar House, Bow Road, East London. (28) During the First World War she worked as a Sister at the Royal London Hospital. This included a spell on the Western Front in France with the Civil Hospital Reserve and was commended for her "gallant and distinguished service in the field." (29)

Six Point Group

Theresa Garnett was one of the founders of the Six Point Group of Great Britain that was formally inaugurated on 17th February 1921. The group focused on what she regarded as the six key issues for women: (i) Satisfactory legislation on child assault; (ii) Satisfactory legislation for the widowed mother; (iii) Satisfactory legislation for the unmarried mother and her child; (iv) Equal rights of guardianship for married parents; (v) Equal pay for teachers and (vi) Equal opportunities for men and women in the civil service. (30)

It had monthly meetings at its headquarters on the top floor of 92 Victoria Street. Other members included Margaret Haig Thomas (president), Ethel Annakin Snowden (vice-president), Elizabeth Robins, Cicely Hamilton, Stella Newsome, Rebecca West, Helen Archdale, Frances Balfour, Charlotte Marsh, Winifred Mayo, Winifred Holtby and Vera Brittain. The SPG Parliamentary committee of supportive MPs was chaired by Philip Snowden. At the time there were only two women MPs: Nancy Astor and Margaret Winteringham. (31)

The SPG drew up "black and white lists" of MPs which were compiled on the basis of previous record on women's issues in the House of Commons. Cheryl Law argues in Suffrage and Power: The Women's Movement, 1918-1928 (2000): "It informed its readers that additional information was available on request from the SPG. It was an ingenious tactic, presented in a readily comprehended format, and the advantage over questionnaires of being compiled without actual recourse to the MPs." (32)

Women were urged to set aside party loyalty and work to defeat the "Blacklisted" members. After the 1922 General Election the SPG was able to report that of 23 MPs on the Blacklist 9 had been defeated, 2 stood down and only 12 had been re-elected. Martin Pugh argues: "In practice, however, this was only a shade more coercive than the pressure being applied by the constitutionists at this time, though their emphasis was perhaps rather more on supporting friends of women's causes." (33)

Between 1931 and 1933, electoral registers record Theresa Garnett as residing at 46 Sandringham Court, Maida Vale, London. Between 1936 and 1938, electoral registers gave her home address as 7 Cornwall Gardens Court, South Kensington. (34) When the 1939 National Register was compiled,Theresa Garnett was living at 18 Lindum Road, Worthing, West Sussex. She is recorded as being a "Radiographer Hospital Nurse Secretary". (35)

On 19th January 1950, Teresa Garnett of 23 Upper Wimpole Street, London, W1, recorded as a 61-year-old "Nurse Secretary", set sail for Australia on R.M.S. Orontes. Five years later, on 11th July 1955, Theresa Garnett, a radiographer of 152 Makepeace Mansions, London, N6 was heading for Colombo onboard the P & O liner Stratheden. (36)

Frances Theresa Garnett of 152 Makepeace Mansions, London, N6, died on 24th May 1966 at Whittington Hospital, Archway Wing, London, at the age of 78. She left £120 which was administered by a town clerk and the borough treasurer.

Primary Sources

(1) Votes for Women (16th July, 1909)

The cases of the fourteen women charged with special offences were taken on Monday, July 12. Thirteen of them were accused of stone-throwing, and after hearing the evidence the magistrate sentenced them all to fine or imprisonment, the period being one month in the case of those who had broken small windows and six weeks in the case of those who had broken plate-glass windows. (Mary Allen, Dove Willcox breaking Government windows in Whitehall)

Miss Theresa Garnett said: "I went no further than the Government have made us go, and we shall not go any further than they make us; they are responsible for all that is being done.

(2) Votes for Women (13th August 1909)

On Wednesday last week I was brought before the magistrate, charged first with striking wardresses.

The first charge was entirely untrue, and was found so by the magistrate, who dismissed the case. Of the second charge there was just this much truth, that I pushed the wardress out of my cell in consequence of her behaviour to me. The magistrate, however, believed her story, which was that I had struck her and injured her, and for this I was sent to prison for a month in the third condition.

Nevertheless, I only served three days of my sentence, as I adopted for the second time in three weeks, the "hunger strike". I was driven up to Holloway in the prison van with Mrs Dove-Willcox, but so terrified did the authorities seem to be of us that I was taken out of the van and securely locked away in the reception cell before Mrs Dove-Willcox was allowed to get out. I asked for the Governor, but was told that he was out, and that I could not see him. I then said that I should refuse to wear prison clothes or to conform to the regulations I was according stripped by the wardresses and taken to one of the cells.

From the onset I determined to refuse all food… When I did this three weeks ago during my previous imprisonment, I did not feel any serious pain until the fourth day, but on this occasion, I was so weak that I felt terribly hungry all the time, and on several occasions went into a faint. I also had severe headache during the whole time.

The evening of the first day that I was in person I found that the light was left burning, and as I lay on my bed this glare prevented my sleeping. Accordingly at eleven o'clock I got up to ring the bell in my cell to ask that it might be extinguished, but I was not able to reach the bell, and fell back in a faint…

The doctor came to me one day and tried to get me to take food, asking me how many votes I thought it was worth if I lost my health for the rest of my life. I said to him, "One vote is worth life itself." "Have you not had more than enough?" He said to me another day. "I have had more than enough already for my comfort," I replied, "but I am prepared to go on to the end." And the end came sooner than I feared it might: I had been faint several times during the three days, and on Saturday afternoon the doctor came and announced to me that I was to be released.

I know that we women are stronger than the Government, and that we can compel them to do us justice.

(3) Votes for Women (17th September 1909)

Lady Constance Lytton was the speaker at the weekly At Home in the Charing Cross Hall, Glasgow, and made a very fine speech, which she received with great applause by a large audience… Next week Miss Theresa Garnett will speak on the Hunger Strike. Open-air meetings are being held all over Glasgow this week.

(4) The Dundee Courier (16th November 1909)

A police inspector stated that as she lashed Mr Churchill with a dog whip she shouted, "You brute, I will show you what English women can do. "Defendant said she had given Mr Churchill the punishment he deserved as representative of this country and unjust Government.

"I am proud," she declared, "of being a woman who has had the great privilege of resenting the intolerable wrong and injustice done to my sex by these Liberal politicians, who are hypocritically denouncing the House of Lords while keeping their countrywomen in political subjection."

The Magistrates bound her over, failing sureties a month's imprisonment. She refused to be bound over, expressing the hope that she would do her business better next time, and she was committed for a month.

(5) Votes for Women (19th November 1909)

Miss Garnett had determined to take vigorous action, and to humiliate Mr Winston Churchill on his arrival by the GWR. Through the magistrate subsequently in court said it was a hysterical act, it was a piece of cool daring such as has not often been witnessed.

Although hemmed in by detectives, who made a semi-circle round the Minister, Miss Garnett rushed right through them with her riding-switch concealed up the sleeve of her coat. Mr Churchill alone saw her coming, and stood fascinated and petrified; he raised his arm up as she approached and thus broke the force of the first blow; she, however, got in a second, and a third, saying, "Take that, in the name of the insulted women of England." He grappled with her, and a looker-on wrested the switch from her hand and gave it to Mr Churchill, who put in his pocket. He was deadly pale, either from fear or passion, but all right; it's all right." This was Bristol's welcome to a statesmanship by his dishonest conduct to the women of Great Britain. Miss Garnett was arrested on a charge of assaulting Mr Churchill on the head with a whip.

(6) Dundee Evening Telegraph (14th December 1909)

Miss Theresa Garnett, Leeds, the Suffragette who used a whip upon Mr Winston Churchill at Bristol, was released from the Horfield Gaol this morning after serving the full term of one month's imprisonment.

Miss Garnett stated she adopted the hunger strike, and was forcibly fed.

As a protest she broke the glass over the gas box in the cell, and set fire to the stuffing of her pillow and mattress.

For this act she was placed in the punishment cell, remaining there eleven days.

(7) David Simkin, Family History Research (6th November, 2023)

Frances Theresa Garnett was born on 17th May 1888 at 33 Stanningley Road, Armley, Leeds, the daughter and third child of Joshua Garnett (1862-1945) and his wife, Frances Theresa, née Armstead (1862-1888).

Joshua Garnett, the son of Joseph Garnett a Yorkshire-born textile worker and an Irish mother, was born in Armley, Leeds, on 14th January 1862. Joshua began his working life as a stoker in a steam-powered woollen mill, but in his twenties, he found employment as an “iron planer” at the Leeds Forge Company, a metal factory that manufactured iron and steel items for the railway industry. The Leeds Forge Company, which had a factory in the Armley district of Leeds, produced locomotive axles, corrugated flues and furnaces for locomotive boilers, steel waggons, and other railway rolling stock. As an "iron & steel planer", Joshua Garnett operated a metalworking machine which cut excess material from the manufactured metal pieces.

In September 1885, in the district of Bramley in the West Riding of Yorkshire, 23-year-old Joshua Garnett married Frances Theresa Armstead (born 1862, Dublin, Ireland), the daughter of Monica Troy and Francis Armstead. In the mid-1860s, the Armstead family had travelled from Ireland to Wortley, an area of Leeds, to find work in the local textile mills. Frances Armstead’s father was a woollen weaver and both her siblings worked in the textile industry. Before he marriage to Joshua Garnett, ‘Fanny’ Armstead was employed as a "worsted Knotter", and it is likely that she met her future husband in her late teens when both were employed in a woollen mill.

In the first three years of their marriage, Joshua and ‘Fanny’ Garnett produced three children. Their first child, Alfred Garnett, was born in New Wortley, West Yorkshire, on 15th January 1886. A second child was born the following year, and their third child, Frances Theresa Garnett (baptised ‘Francisca Theresia’ by a Roman Catholic priest on the day of her birth) was born at the family home in Stanningley Road, Armley, Leeds, on Thursday, 17th May 1888.

A few weeks after the birth of her daughter (Frances Theresa) Mrs Frances Garnett, became ill, complaining that she “did not feel well in her head”. Mrs Garnett started to talk in “a rambling manner” and was “very much excited”. Mrs Garnett’s doctor eventually suggested that she “should be removed to the Asylum.” Joshua Garnett, accompanied by Mrs Mary Rice (Fanny’s married sister), took his afflicted wife by a horse-driven cab to the West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum at Stanley-cum -Wrenthorp, near Wakefield, West Yorkshire. Mrs Garnett arrived at the West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum on Monday, 11th June 1888, at 12.15 pm. Fanny Garnett received some attention from the asylum’s medical officer, but she slipped into a coma and died at 8.50 pm that same day. She was 26 years old at the time of her death. The County Coroner’s report on Mrs Frances Garrett’s demise concluded that “the cause of death was exhaustion from puerperal mania”. (The mental illness then called “puerperal mania”, but now referred to as postpartum or postnatal psychosis, generally affects a woman soon after having a baby. Sufferers from postpartum psychosis often have a family history of mental illness and is sometimes linked to depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia).

Joshua Garnett was left widowed at 26 years of age, with three infant children. According to Joshua Garnett, at the time of his wife’s death, “she had 3 children, and all are living”. Sometime before the census taken on 5th April 1891, Joshua Garnett’s middle child had died. The 1891 Census records 29-year-old Joshua Garnett, a widower, employed as a “Mechanic - Metal Planer”, residing with his two children Alfred, aged 5, and two-year-old Frances, at the home of his parents, Mary Ann & Joseph Garnett. Joshua had given up his house at No. 33 Stanningley Road, Armley, and moved next door to number 35. Joshua’s father, Joseph Garnett, a 55-year-old “woolworker”, was the Head of the household at 35 Stanningley Road, Armley, Leeds, a house that contained his wife, Mary Ann, his widowed son, Joshua, an unmarried daughter in her twenties (Mary Garnett), his two grandchildren, (Alfred and Frances Garnett), and a teenage relative, 19-year-old John E. King.

A decade later, Joshua Garnett and his two children were still residing at the home of Joseph Garnett at 35 Stanningley Road, Armley. Joseph Garnett, the ‘Head of Household’, was now a widower (his wife, Mary Ann Garnett, had died in 1892) but, at 64 years of age, he was still working in a woollen mill. Thirty-nine-year-old Joshua Garnett was still employed as a “metal planer”. Joshua’s son, 15-year-old Alfred Garnett, was working as an “electric crane driver”. No occupation is given for his 12-year-old daughter Frances Theresa Garnett but presumably she was still at school.

When the 1911 Census was taken, Frances Theresa Garnett, now aged 22, was recorded as a “Hospital Nurse in Training” at Harley College, Tredegar House, Bow Road, East London. According to the census return, the nurses were doing their training at the London Hospital (now known as the Royal London Hospital) in Whitechapel Road.

During the First World War, Frances Theresa Garnett served as a nurse in Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) and by the end of the war she had risen to the position of ‘Sister’ and is recorded as such in World War One Pension Ledgers and Index Cards for the period 1914-1923. Frances Theresa Garnett is not recorded in the 1921 Census of England and Wales so she might have been working as a nurse abroad when the census was carried out. A World War One index card notes that Frances Theresa Garnett had a home address in Honor Oak, South London.

Between 1931 and 1933, electoral registers record Frances Theresa Garnett as residing at 46 Sandringham Court, Maida Vale, London. Between 1936 and 1938, electoral registers give the home address of Frances Theresa Garnett as 7 Cornwall Gardens Court, South Kensington.

When the General Register of 1939 was compiled, Frances Theresa Garnett was living at 18 Lindum Road, Worthing, West Sussex. The 1939 Register records the personal occupation of 51-year-old Miss Garnett as a “Radiographer Hospital Nurse Secretary”. She was sharing the house in Lindum Road with two elderly ladies who are described as retired “L.C.C. School Teachers”.

Between 1930 and 1955, Frances Theresa Garnett made a number of journeys to Morocco, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Australia. For instance, on 2nd April 1931, Miss Frances Garrett, described as a 42-year-old radiographer, was on the outward passenger list for the P & O steam ship ‘Naldera’ bound for Brisbane, Australia. On 19th January 1950, Miss F. T. Garnett of 23 Upper Wimpole Street, London, W1, recorded as a 61-year-old “Nurse Secretary”, set sail for Australia on R.M.S. ‘Orontes’. Five years later, on 11th July 1955, Frances Theresa Garnett, a radiographer of 152 Makepeace Mansions, London, N6 was heading for Colombo onboard the P & O liner “Stratheden”.

Frances Theresa Garnett of 152 Makepeace Mansions, London, N6, died on 24th May 1966 at Whittington Hospital, Archway Wing, London, at the age of 78. The Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations) notes that she left £120 which was administered by a town clerk and the borough treasurer.

Student Activities

References

(1) Census Data (1881)

(2) David Simkin, Family History Research (6th November, 2023)

(3) Coroner's Report on the death of Frances Garnett (12th June, 1888)

(4) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 237

(5) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 143

(6) Votes for Women (16th July, 1909)

(7) Votes for Women (13th August 1909)

(8) Elizabeth Crawford, Theresa Garnett: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September, 2004)

(9) Votes for Women (13th August 1909)

(10) The Liverpool Courier (21st August, 1909)

(11) The Times (21st August, 1909)

(12) Votes for Women (27th August, 1909)

(13) Robert Lloyd George, David and Winston: How a Friendship Changed History (2006) pages 70-71

(14) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) pages 134-135

(15) Votes for Women (29th October, 1909)

(16) The Dundee Courier (18th October 1909)

(17) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 178

(18) Votes for Women (19th November, 1909)

(19) The Dundee Courier (16th November 1909)

(20) Votes for Women (19th November 1909)

(21) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 237

(22) Mary Blathwayt, diary entry (15th November 1909)

(23) The Dundee Courier (16th November 1909)

(24) Emily Blathwayt, diary entry (16th November 1909)

(25) Elizabeth Crawford, Theresa Garnett: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September, 2004)

(26) Votes for Women (18th March, 1909)

(27) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 237

(28) Census Data (1911)

(29) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 538

(30) Margaret Haig Thomas, Time and Tide (21st January 1921)

(31) Angela V. John, Turning the Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda (2013) page 369-374

(32) Cheryl Law, Suffrage and Power: The Women's Movement, 1918-1928 (2000) page 145

(33) Martin Pugh, Women and the Women's Movement in Britain 1914-1959 (1992) page 49

(34) David Simkin, Family History Research (6th November, 2023)

(35) 1939 National Register (29th September 1939)

(36) David Simkin, Family History Research (6th November, 2023)