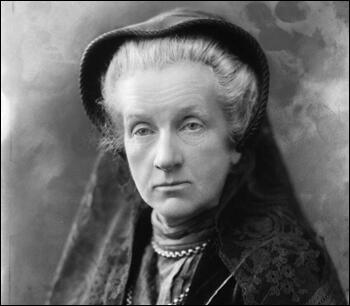

Frances Balfour

Frances Balfour, the daughter of George Douglas Campbell, eighth duke of Argyll (1823–1900), was born on 22nd February 1858. The tenth of twelve children, Frances had a hip-joint disease and from early childhood was constantly in pain and walked with a limp.

Her biographer, Joan B. Huffman, has pointed out: " Her formal education was provided by an English governess. However, the main method by which she learned throughout her life was by listening to and participating in the conversations, particularly at the dinner table, of her parents, in-laws, and male acquaintances, especially ministers and politicians, whose company and friendship she preferred."

The Duke and Duchess of Argyll were both supporters the Liberal Party in Parliament and were involved in several different campaigns for social reform. Frances also helped with these campaigns as a child and one way she contributed was to knit garments to be sent to the children of ex-slaves.

Frances married Eustace Balfour in 1879. At first the Duke of Argyll had opposed the relationship because he came from a well-known Tory family. Eustace's uncle, the Marquis of Salisbury, had three spells as Prime Minister. Eustace's elder brother, Arthur Balfour, was also a Conservative politician and was later to become Britain's Prime Minister (1902-1905). Unlike his brother and uncle, Eustace did not take an active role in politics. However, he shared his family's Tory views and this caused conflict between him and his wife. Frances was a passionate Liberal and was a loyal supporter of William Gladstone and his government. The couple never overcame these political differences and spent less and less time together. Eustace was a heavy drinker and eventually became an alcoholic. Eustace died in 1911.

Membership of the Women's Liberal Unionist Association brought her into contact with feminists such as Marie Corbett and Eva Maclaren. In 1887 Balfour joined with Corbett and Maclaren in the recently formed Liberal Women's Suffrage Society. Frances Balfour wrote in her journal: "I don't remember any date, in which I was not a passive believer in the rights of women to be recognised as full citizens in this country. No one ever spoke to me on the subject except as shocking or ridiculous, more often as an idea that was wicked, immodest and unwomanly."

Her biographer, Joan B. Huffman has argued: "Lady Frances began her political work when she joined the campaign to secure the enfranchisement of British women. Indeed, she was one of the highest ranking members of the aristocracy to assume a leadership role in the women's suffrage movement. One of the few women of her class to agitate for votes for women from the 1880s onwards, she became a leader of the constitutional suffragists. Her feminism, like much of the rest of her political philosophy, derived from her personal experiences. In her youth and adolescence she heard the arguments against slavery advanced by members of her family (her mother and grandmother, Harriet, duchess of Sutherland, were ardent abolitionists). As a young woman she was thwarted in her desire to become a nurse and frustrated because she could observe, but not aspire to a seat in, parliament. Thus, as a feminist, Lady Frances espoused equal rights for women and was absolutely convinced that women should be permitted to study and train for careers in all the professions on the same terms as men."

In 1896 Frances Balfour became president of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. A position she was to hold for the next eighteen years. She was a good speaker and often appeared at suffragist public meetings. She was also well-placed to try and influence leading members of the House of Commons. Frances and her sister-in-law, Betty Balfour, tried hard to persuade Arthur Balfour, to support women's suffrage. Although Balfour accepted the justice of women's rights, his lack of enthusiasm meant that he was unwilling to fight for the cause inside the largely unsympathetic Conservative Party.

Balfour was a completely non-violent suffragist and was totally opposed to the militant actions of the Women's Political and Social Union (WSPU). Francis disagreed with her sister-in-law, Constance Lytton, who joined the WSPU and had to endure several periods of imprisonment. Frances was also opposed to socialism and was very unhappy with the decision of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies in 1912 to support the Labour Party.

After women were granted the vote, Balfour spent her time writing books and articles. This included five biographies: Lady Victoria Campbell (1911), The Life and Letters of the Reverend James MacGregor (1912), Dr Elsie Inglis (1918), The Life of George, Fourth Earl of Aberdeen (1923), and A Memoir of Lord Balfour of Burleigh (1925) and an autobiography, Me Obliviscaris (1930), where she recalled: "My gifts, such as they were, lay in being a sort of liaison officer between Suffrage and the Houses of Parliament, and being possessed of a good platform voice.

Lady Frances Balfour died at her London home, 32 Addison Road, Kensington, on 25th February 1931 from pneumonia and heart failure. She was buried at Whittingehame, the Balfour family home in East Lothian.

Primary Sources

(1) Frances Balfour, Me Obliviscaris (1930)

On the table amid her work was a small glass, in which stood a single flower, or sprig of green, and not infrequently a little bit of shamrock, in strange outward contrast to the large uncouth figure of Miss Blackburn, her shortsighted eyes always close to the papers she was working at... Her face was greatly marred by long illness, most patiently borne, but through its plainness there shone the countenance of a great soul.... Miss Blackburn was a born chronicler and antiquarian... Her knowledge and experience was at everyone's disposal.

(2) In July 1911, Frances Balfour gave a talk on women's suffrage at Coombe House, East Grinstead. The speech was reported in the local newspaper, East Grinstead Observer.

Lady Frances Balfour gave a talk on Women's Suffrage. Lady Balfour told the meeting that as the law stood women were classed with paupers, felons and lunatics as being unfit to exercise the franchise… She went on to speak of the great struggle women had in the matters of education, the difficulty they had in getting into the medical profession and taking part in local government… One of the arguments used against women having the vote was that they could not fight, therefore they had no right to a voice in these matters dealing with wars, but this was ridiculous, for who was it who suffered most in time of war? Women, because they lost their husbands and sons.

(3) After joining the WSPU Annie Kenney moved to London to work as a full-time organiser. On one occasion she was asked to represent the WSPU at a meeting with Arthur Balfour, the leader of the Conservative Party.

Lady Balfour took me to see Arthur Balfour privately. When we arrived he asked me to tell him what I thought he could do for us. I had a long talk with him… There he sat in age armchair, his long spidery legs stretched out… He constantly sniffed at a small bottle. I wondered what it contained and thought the conversation might be upsetting him… It was time to go and he had not committed himself any more than I expected he would.

(4) Frances and Betty Balfour observed the arrest of several members of the WSPU on 29th June 1909. Frances Balfour wrote a letter to Millicent Fawcett describing what she saw.

I am just back from a night with the militants… The police in solid lines turned the women into Victoria Street. Here we saw several arrests, the women all showing extraordinary courage in the rough rushes of the crowd round them… Two women, exactly in front of us threw stones at the windows. Poor shots; I don't think the glass was cracked. A policeman flew round at them and had his arms round their necks before we could wink. The courage that dares this handling I do admire. There is a fine spirit, but whether it is not rather thrown away on these tactics remains a doubt in my mind.

(5) Mrs. Arnold Forster, letter to Lady Balfour on news of Constance Lytton's death.

Few things affected my whole vision of life more than her example. It made one ashamed of half-hearted faith, and of one's cowardice. It set a standard, by which women felt they must measure themselves, and finding themselves wanting, felt that they must live more finely. That is what heroes and saints do for us, they lift up our standards of faith and achievement. I feel today the same deep impulse of gratitude and love that we felt in the dark days when she lay in prison for us.

(6) Mrs. Coombe Tennant, wrote a letter to Lady Balfour on hearing about the death of Constance Lytton.

Somehow I cannot think of the passing of such as your sister Constance with any sense of break - only of a sense of a great emergence into ampler freedom and activity… I don't in the least care whether her actions were wise or foolish. I simply say she had a share in altering the world and shaping thought among women. Who could ask for a better epitaph?"