Marie Corbett

Marie Corbett, the daughter of George and Eliza Gray, was born in Tunbridge Wells on 30th April 1859. George Gray was a successful entrepreneur who made a fortune from importing fruit and producing confectionery. Both George and Eliza were ardent Liberals who supported many progressive causes. (1)

In 1881 Marie married a wealthy barrister, Charles Corbett, who had an 840-acre estate at Woodgate in the village of Danehill in Sussex. The couple believed they had a responsibility to help the less fortunate members of the community and for many years the couple provided free legal advice for people living in the area. (2)

After the passing of the Municipal Franchise Act Marie became a member of the Uckfield Board of Guardians. Later she was the first woman to serve on the Uckfield District Council. Marie also took an active role in national politics and was one of the three women who founded the Liberal Women's Suffrage Society. When attempts to persuade the Liberal Government to introduce measures to give women the vote ended in failure, Marie became active in the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies. (3)

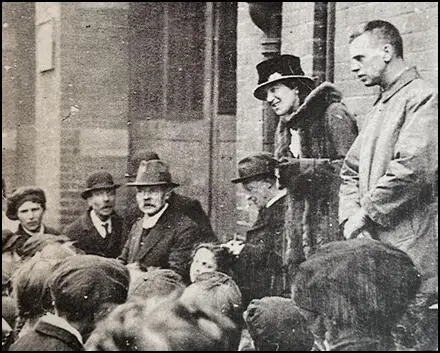

Marie Corbett in Danehill

Marie Corbett was "appalled by the conditions in which orphaned and abandoned children were living in wards with the old and mentally afflicted." She reformed conditions in the workhouse, and gradually removed all the children, whom she boarded out with village families. (4)

The couple had three children: Margery Corbett Ashby (1882), Adrian Ashby (1883) and Cicely Corbett Fisher (1885). The children were educated at home by Lina Eckenstein. Charles taught the girls classics, history and mathematics and Marie taught them scripture and the piano. A local woman gave them lessons in French and German. (5)

Her daughter, recalled in her memoirs: "My mother became an energetic cyclist, rebuked by her neighbours for showing inches of extremely pretty feet and ankles; regarded as highly indecorous. It was not only to the ankles that the neighbours objected. My parents were Liberals… at that period as much hated and distrusted by the gentry as Communists are today, and regarded as traitors to their class. In consequence they boycotted them… I suspect this boycott threw my energetic mother even more fervently into good works amongst the villagers, where, in the days before the welfare state, poverty was widespread." (6)

A friend, Mary Hamilton, later commented: "Marie Corbett, was an ardent Feminist, one small external sign being the fact that she regularly wore the breeches she had taken to when bicycling came in, at least a decade before war-time made them permissible. She was a woman of great drive, active in local affairs and local government and all good causes." (7)

Louisa Martindale was another family friend: "In the 1860s women realised that the only way to civil rights, higher education, and equal status lay through the parliamentary franchise… My mother became friends with Marie Corbett of Danehill, a remarkable woman who not only threw herself heart and soul into the cause, but also educated her daughters (now Mrs Margery Corbett Ashby and Mrs Cicely Corbett Fisher) to take the leading place they have in public life." (8)

Women's Suffrage

Charles Corbett was the Liberal Party candidate in East Grinstead. In the 1906 General Election took place the following month. The Liberal Party won 397 seats (48.9%) compared to the Conservative Party's 156 seats (43.4%). The Labour Party, led by Keir Hardie did well, increasing their seats from 2 to 29. In the landslide victory Arthur Balfour lost his seat as did most of his cabinet ministers. Corbett won the seat by 262 votes. Margot Asquith wrote: "When the final figures of the Elections were published everyone was stunned, and it certainly looks as if it were the end of the great Tory Party as we have known it." (9)

Unlike the Liberal leadership, Charles Corbett strongly supported votes for women and helped form the East Grinstead branch of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage. Disappointed with the poor record of the Liberal Party with respect to women's suffrage, Marie left the Women's Liberal Federation and with her two daughters helped form the Liberal Suffrage Group. In 1907 Margery Corbett decided to become a full-time campaigner for women's rights and became secretary of the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). (10) "I dealt with the correspondence, produced the Union's paper, becoming its editor, and learned by experience how to select, produce and edit material - the Board of course laid down the policy." In 1908 Margery was voted on to the executive board of the NUWSS. (11)

Marie Corbett's sister-in-law, Catherine Corbett, was a member of the Women's Social & Political Union (WSPU). She was a member of the team led by Jessie Kenney and included Vera Wentworth, Mary Phillips and Elsie Howey, that decided to target the prime minister, Herbert Asquith. On 28th April, 1909, Catherine Corbett according to the Daily Mirror, a "tall dark and handsome lady" accosted Asquith as he left a meeting in Whitehall. Corbett told a journalist that Asquith was a "little surprised and reserved but he showed no resentment". However, he did add: "I think you are very silly." (12)

Marie's other daughter, Cicely Corbett was also involved in the struggle for women's suffrage in East Grinstead. The three women would hold meetings every Wednesday evening on the "High Street slope". In one meeting in October 1911 Marie argued that "chivalry would not die when women had the vote" and pointed out that "men were now banding themselves together to help get women the vote." (13)

In 1911 Marie Corbett and her two daughters joined with Muriel, Countess de la Warr and Lila Durham to form the East Grinstead Suffrage Society. Membership was always small and meetings rarely attracted more than ten members. At the same time Lady Lucinda Musgrave, who lived in a 400-year-old house called Hurst-an-Clays in the town, formed a local branch of the Anti-Suffrage Society. Lady Musgrave argued "that she was strongly against the franchise being extended to women, for she did not think it would do any good whatsoever, and in sex interests, would do a lot of harm.... Women were not equal to men in endurance or nervous energy, and she thought she might say, on the whole, in intellect." She added "that in a recent canvas by postcard, of the 200 odd women in East Grinstead, they found that 80 did not want the vote, 40 did want the vote and the remainder would not sufficiently interested in replying." (14)

Marie and her daughters also organised feminist plays to be performed at the Whitehall Theatre in the town. This included How the Vote was Won, a play written by Cicely Hamilton, The local newspaper reported: The dramatic entertainment promoted by the East Grinstead Suffrage Society given at the Whitehall Theatre on Monday evening attracted a large audience. The play was 'How the Vote Was Won'. The audience showed evident sign of approval of many portions of the dialogue. The cast was as follows: Victoria Addison, Lydia Sydney, Ethel Hart, Edith Pitcher, Mildred Orme and Inez Bensusan." (15)

Cicely Corbett

After completing her university studies, Cicely Corbett went to work with Clementina Black at the Women's Industrial Council, an organisation that campaigned against low pay and bad working conditions. By 1910 women made up almost one third of the working population. The vast majority worked in jobs with low pay and poor conditions. Cicely was also an active member of the Anti-Sweating League and in the years preceding the start of the First World War, she organised several conferences on the subject. At the time sweated labour was defined as "(i) working long hours, (ii) for low wages, (iii) under insanitary conditions". (16)

Most sweated labour took place in the homes of workers. Cicely Corbett's conferences often included speeches and demonstrations of sweated labour by women from industrial towns and cities. At another meeting Cicely argued: "Women are often forced out into the labour market because men either could not or would not earn their living for them, and yet when a minimum wage was fixed for government employees, women were not included in it, and that decision had led to worse sweating of women than before, which would never have been possible if women were included among the voters." (17)

Children employed after school hours in the home were also victims of sweated labour. Cicely argued: "Chief among these evils of sweated labour is the exploitation of child labour. Children of six years and upwards were employed after school hours, in helping to add to the family output and even infants of 3, 4 and 5 years of age work anything from 3 to 6 hours a day in such labour as carding hooks and eyes to add a few pence per week to the wages of the household." (18)

Marie Corbett was a strong opponent of the violent actions of the Women Social & Political Union: In March 1912 the East Grinstead Observer published a letter from her that stated: "There cannot be more than a few hundred in all who have put themselves under the leadership of the Social and Political Union for the commission of lawless activities. The members of the East Grinstead Women's Women's Suffrage Society strongly disapprove of acts of violence." (19)

Women's Pilgrimage

By 1913 the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) had nearly had 100,000 members. Katherine Harley, a senior figure in the NUWSS, suggested holding a Woman's Suffrage Pilgrimage in order to show Parliament how many women wanted the vote. Women marched to London from all around England and Wales with the intention of meeting up in Hyde Park on 26th July. (20)

The East Grinstead Suffrage Society decided to take part in this pilgrimage. It was decided to have a large public meeting in the town before setting off to London. Speakers at the meeting included Marie Corbett, Laurence Housman and Edward Steer. The local newspaper reported: "The non-militant section of the advocates of securing women’s suffrage had arranged a march and public meeting on its way to the great demonstration in London. The procession was not an imposing one. It consisted of about ten ladies who were members of the Suffrage Society. Mrs. Marie Corbett led the way carrying a silken banner bearing the arms of East Grinstead."

It later emerged that local members of the Conservative Party, many of them involved in the brewing industry, had arranged for youths to break up the meeting. "The reception, which the little band of ladies got, was no means friendly. Yells and hooting greeted them throughout most of the entire march, and they were the targets for occasional pieces of turf, especially when they passed through Queen’s Road. In the High Street they found a crowd of about 1,500 people awaiting them. Edward Steer had promised to act as chairman, and taking his stand against one of the trees on the slope he began by saying, 'Ladies and Gentlemen'. This was practically as far as he got with his speech. Immediately there was an outburst of yells and laughter and shouting. Laurence Housman, the famous writer, got no better than Mr. Steer. By this time pieces of turf and a few ripe tomatoes and highly seasoned eggs were flying about, and were not always received by the person they were intended for. The unsavoury odur of eggs was noticeable over a considerable area. Unhappily, Miss Helen Hoare of Charlwood Farm, was struck in the face with a missile and received a cut on the cheek and was taken away for treatment.... Mrs. Marie Corbett slipped away and took up a position lower down the High Street on the steps of the drinking fountain. A young clergyman who appealed for fair play was roughly hustled and lost his hat. Mrs. Corbett had began to speak from the fountain steps but the crowd moved down the High Street and broke up her small meeting." (21)

Wallace Hills, the editor of the East Grinstead Observer, and Secretary of the East Grinstead Conservative Association, admitted that this should not have happened. "The most bitter opponents of female suffrage can have no reason to feel proud about the break-up of the open-air meeting at East Grinstead on Tuesday evening, and the whole event was a distinct discredit to the town." He ended the article with a quote from one of the organisers of the meeting that "the tradesmen who had saved up rotten eggs to throw at ladies ought to be ashamed of themselves." (22)

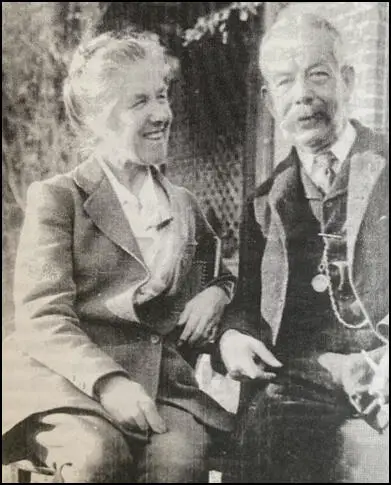

Margery Corbett Ashby

In May 1916 Millicent Garrett Fawcett wrote to Herbert Asquith that women deserved the vote for their war efforts. In August he told the House of Commons that he had now changed his mind and that he intended to introduce legislation that would give women the vote. On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. MPs rejected the idea of granting the vote to women on the same terms as men. Lilian Lenton, who had played an important role in the militant campaign later recalled: "Personally, I didn't vote for a long time, because I hadn't either a husband or furniture, although I was over 30." (23)

The Qualification of Women Act was passed in February, 1918. The Manchester Guardian reported: "The Representation of the People Bill, which doubles the electorate, giving the Parliamentary vote to about six million women and placing soldiers and sailors over 19 on the register (with a proxy vote for those on service abroad), simplifies the registration system, greatly reduces the cost of elections, and provides that they shall all take place on one day, and by a redistribution of seats tends to give a vote the same value everywhere, passed both Houses yesterday and received the Royal assent." (24)

The First World War ended in November 1918. Millicent Fawcett lost "no fewer than twenty-nine members of her extended family, including two nephews" in the war. Whereas the WSPU "were prepared to accept votes for women on any terms the government had to offer... the NUWSS continued to press its old case for equality with men". She was urged to stand for Parliament in the 1918 General Election, but aged seventy-one, she decided to retire from politics. (25)

Margery Corbett, who had married Brian Ashby, was invited by letter to be the Liberal Party candidate in the Ladywood constituency. This was the safe seat of Neville Chamberlain. "That morning there was a meeting of the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies, so I gaily waved the invitation, expecting amusement and some resentment at a woman being asked to take on a fight bound to end in ignominious defeat. To my surprise, there was a unanimous chorus that I must accept. It would help to accustom the public to the idea of women candidates, and the immediate result would be unimportant." (26)

David Lloyd George did a deal with Andrew Bonar Law that the Conservative Party would not stand against Liberal Party members who had supported the coalition government and had voted for him in the Maurice Debate. It was agreed that the Conservatives could then concentrate their efforts on taking on the Labour Party and the official Liberal Party that supported their former leader, H. H. Asquith. The secretary to the Cabinet, Maurice Hankey, commented: "My opinion is that the P.M. is assuming too much the role of a dictator and that he is heading for very serious trouble." (27)

Margery Corbett Ashby had stayed loyal to Asquith: She later explained: "The political circumstances were as unpleasant as possible. Lloyd George's coupon election was in full swing (the coupons were endorsements given to those Liberal candidates who supported Lloyd George, as opposed to those in the Asquith camp), and naturally, being an Asquith Liberal, I was not given the coupon. The Lloyd George cry to squeeze Germany 'until the pips fell out' was horrifying to me, as wickedly damaging to the recovery of all the nations at war. I hoped to get the women's vote and that of new and inexperienced voters." (28)

The General Election results was a landslide victory for David Lloyd George and the Coalition government: Conservative Party (382); Coalition Liberal (127), National Labour Coalition (4) and Coalition National Democrats (9) . The Labour Party won only 57 seats and lost most of its leaders including Arthur Henderson, Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett. The Liberal Party returned 36 seats and its leader H. H. Asquith was defeated at East Fife. (29)

Ashby came third with 11% of the vote: "The result of the election over the country was a resounding victory for Lloyd George and a coalition government, but I had the satisfaction of polling as many votes as did the nine Liberal candidates in neighbouring constituencies. Being a woman was neither an advantage nor a disadvantage.... Birmingham was my first attempt to get into Parliament. My subsequent election contests all ended in defeat, as I was always invited to fight a hopeless constituency, usually at the last minute, when there was no chance to 'nurse' the constituency as is essential for a real chance of success." (30)

In 1919 Margery was a member of the International Women Suffrage Alliance who attended the Versailles Peace Conference as a substitute for Millicent Garrett Fawcett. Along with Mary Allen she advised Germany on the founding of the German women's police force. (31)

The following year Margery attended the International Women Suffrage Alliance held a meeting in Geneva. "Surely after this prolonged agony mankind would renounce the use of war. The League of Nations had been set up. A new world seemed to have arisen out of bloodshed, hatred and ruin, a new world that promised democratic progress and a better understanding among nations. The Congress itself welcomed women MPs and government delegates, and women had the vote in fourteen countries." (32)

Margery Corbett Ashby remained a member of the Women's Freedom League and in 1923 she was elected president of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (renamed the International Alliance of Women in 1926). It widened its interests and concerned itself with other issues of importance to women - for example, equality of opportunity in employment, adequate representation on public bodies, the nationality of married women, equal moral standards for both sexes, and family allowances. It also took up the cause of peace. Margery and the organisation became a keen supporter of the League of Nations, whose assembly she attended regularly. (33)

Margery Corbett Ashby was also elected President of the Women's Liberal Federation. However, she had difficulty dealing with senior members of the Liberal Party who were still arguing against all women over 21 from having the vote. This included Herbert Henry Asquith, the leader of the party. She told his daughter, Violet Bonham Carter: "I had a friendly talk with Lady Violet, pointing out how hard it was for me to be a member of the Liberal Party when her father thought women too unreliable or too stupid or too emotional to be given the vote." (34)

Ashby was also a member of the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC). Eleanor Rathbone became leader of the organisation and she proposed a six point reform programme. (1) Equal pay for equal work, involving an open field for women in industry and the professions. (2) An equal standard of sex morals as between men and women, involving a reform of the existing divorce law which condoned adultery by the husband, as well as reform of the laws dealing with solicitation and prostitution. (3) The introduction of legislation to provide pensions for civilian widows with dependent children. (4) The equalization of the franchise and the return to Parliament of women candidates pledged to the equality programme. (5) The legal recognition of mothers as equal guardians with fathers of their children. (6) The opening of the legal profession and the magistracy to women. (35)

Final Years

After the First World War she continued her work as a Poor Law Guardian. (36) According to Jenifer Hart: "At the peak she had forty children with foster parents, for when she had emptied Uckfield workhouse, she took children from Eastbourne workhouse and from a London borough." (37)

Margery Corbett-Ashby pointed out: "My mother's care and interest for her family of orphans took many forms, and I remember two occasions when much later I was involved in their problems. In the early 1920s news came to me through a friend of a sad case of a young girl of good family, the mother of an illegitimate child, whose parents were ready to take her back home (quite a concession in those days), but not the child. I pased on the news to my mother... My mother asked if she would adopt this baby, and she went home to consult her husband, who agreed... Another time my mother came home from the workhouse with an orphan baby. She was the loveliest little girl, with tiny, beautifully-shaped hands and feet... My mother took care of her, and became so devoted that she would have adopted her, but knew it was most unwise at her age. A young married couple living near longed for a child, but realised that the husband's war wounds made this impossible. They came, they saw and were conquered. The baby was their greatest joy." (38)

Marie Corbett died on 28th April 1932. Several former inhabitants of the workhouse wrote to the family, from as far away as Australia and Canada, and the most common phrase used was "she was my best friend". (39)

Primary Sources

(1) Margery Corbett Ashby, Memoirs (1997)

My mother became an energetic cyclist, rebuked by her neighbours for showing inches of extremely pretty feet and ankles; regarded as highly indecorous. It was not only to the ankles that the neighbours objected. My parents were Liberals… at that period as much hated and distrusted by the gentry as Communists are today, and regarded as traitors to their class. In consequence they boycotted them… I suspect this boycott threw my energetic mother even more fervently into good works amongst the villagers, where, in the days before the welfare state, poverty was widespread.

(2) Mary Hamilton, Remembering Good Friends (1944)

Margery's mother, Marie Corbett, was an ardent Feminist, one small external sign being the fact that she regularly wore the breeches she had taken to when bicycling came in, at least a decade before war-time made them permissible. She was a woman of great drive, active in local affairs and local government and all good causes. The house was apt to swarm with people. The Corbett's hospitality was in the best English tradition. Friends of Margery, of her younger sister Cicely - extravagantly pretty, and at the time we were at Cambridge, preparing to go Oxford and of her elder brother Adrian, then at Oxford, assembled for dances and week-end parties…. At college Margery was intensely keen on civil liberties, free trade, international good will, democracy… She spends time and energy without stint or personal ambition… She has an immense sense of duty, and must have spent a very large part of her entire life on committees and at meetings. Not to like her is and always has been impossible; she has charm and complete sincerity, and has made a success of life, in its essential relationships. She was a good daughter: she is a good wife and mother. The one boy, born during the 1914 war, when his father was in France with the B.E.F., was, as a baby, so delicate that it did not seem possible he should live; Margery insisted that he should; he has grown up a superb physical specimen.

(3) Hilda Martindale, From One Generation to Another (1944)

In the 1860s mother began reading widely, and learnt how Mary Wollstonecraft had vindicated the rights of women in burning words, how Caroline Norton had struggled for her rights over her children, and how Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson showed what determination was needed by young women who wished for academic or professional education. She read Barbara Bodichon's Englishwomen's Journal, which discovered and exposed the obstacles to the employment of educated women, and she learnt about Florence Nightingale and her work on the vast problem of nursing and sanitary administration. In the 1860s women realised that the only way to civil rights, higher education, and equal status lay through the parliamentary franchise… My mother became friends with Marie Corbett of Danehill, a remarkable woman who not only threw herself heart and soul into the cause, but also educated her daughters (now Mrs Margery Corbett Ashby and Mrs Cicely Corbett Fisher) to take the leading place they have in public life.

The overwhelming victory of the Liberal Party at the polls in January 1906 gave them fresh hope but many of the most ardent women political workers were disillusioned; amongst these was my mother…. Henceforth she worked chiefly for the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, which was carrying on the work of organisation amongst those women who believed that the cause of freedom could be won without violence.

(4) Marie Corbett, letter to East Grinstead Observer (16th March, 1912)

Those guilty of disturbances on Friday and Monday are a small and decreasing minority amongst suffragettes. There cannot be more than a few hundred in all who have put themselves under the leadership of the Social and Political Union for the commission of lawless activities. The members of the East Grinstead Women's Women's Suffrage Society strongly disapprove of acts of violence.

(5) On 26th July 1913, East Grinstead Observer reported a riot that had taken place in the town three days previously.

The main streets of East Grinstead were disgraced by some extraordinary proceedings on Tuesday evening. The non-militant section of the advocates of securing women’s suffrage had arranged a march and public meeting on its way to the great demonstration in London. The "procession" was not an imposing one. It consisted of about ten ladies who were members of the Suffrage Society. Mrs. Marie Corbett led the way carrying a silken banner bearing the arms of East Grinstead. The reception, which the little band of ladies got, was no means friendly. Yells and hooting greeted them throughout most of the entire march, and they were the targets for occasional pieces of turf, especially when they passed through Queen’s Road. In the High Street they found a crowd of about 1,500 people awaiting them.

Edward Steer had promised to act as chairman, and taking his stand against one of the trees on the slope he began by saying, "Ladies and Gentlemen". This was practically as far as he got with his speech. Immediately there was an outburst of yells and laughter and shouting. Laurence Housman, the famous writer, got no better than Mr. Steer. By this time pieces of turf and a few ripe tomatoes and highly seasoned eggs were flying about, and were not always received by the person they were intended for. The unsavoury odur of eggs was noticeable over a considerable area. Unhappily, Miss Helen Hoare of Charlwood Farm, was struck in the face with a missile and received a cut on the cheek and was taken away for treatment.

Some of the women were invited to take shelter in Mr. Allwork’s house, but as they entered the crowd rushed the doorway and forced themselves into the house. The police arrived and the ladies were taken out the back way and escorted them to the Dorset Arms Hotel, their headquarters, and this was for a long time besieged by a yelling mob…. Mrs. Marie Corbett slipped away and took up a position lower down the High Street on the steps of the drinking fountain. A young clergyman who appealed for fair play was roughly hustled and lost his hat. Mrs. Corbett had began to speak from the fountain steps but the crowd moved down the High Street and broke up her small meeting.

(6) Marie Corbett was one of the first women in Britain to be elected as a Poor Law Guardian. Her daughter Margery Corbett Ashby described her mother's work as a Poor Law Guardian in her book Memoirs (1997).

My mother visited the local Uckfield Workhouse and was appalled by the conditions in which orphaned and abandoned children were living in wards with the old and mentally afflicted. She stood for election as Poor Law Guardian, and became one of the first women in the country to be Guardian and Rural District Councillor. She reformed conditions in the workhouse, and gradually removed all the children, whom she boarded out with village families… When she had emptied Uckfield Workhouse, she took children from Eastbourne Workhouse and from a London borough. When she died, many of these former inhabitants of the workhouse wrote to me… and they all used the same phrase: "She was my best friend."