Anti-Suffrage Society

William Cremer was one of the leading opponents of women's suffrage. Hansard reported a speech he made in the House of Commons on women's suffrage on 25th April, 1906, he argued: "He (William Cremer) had always contended that if we opened the door and enfranchised ever so small a number of females, they could not possibly close it, and that it ultimately meant adult suffrage. The government of the country would therefore be handed over to a majority who would not be men, but women. Women are creatures of impulse and emotion and did not decide questions on the ground of reason as men did. He was sometimes described as a woman-hater, but he had had two wives, and he thought that was the best answer he could give to those who called him a woman-hater. He was too fond of them to drag them into the political arena and to ask them to undertake responsibilities, duties and obligations which they did not understand and did not care for."

In the summer of 1908 the famous author, Mary Humphry Ward, was approached by Lord Curzon and William Cremer and asked to become the first president of the Anti-Suffrage League. Ward agreed and on 8th July, 1908 the organisation published its manifesto. It included the following: "It is time that the women who are opposed to the concession of the parliamentary franchise to women should make themselves fully and widely heard. The matter is urgent. Unless those who hold that the success of the women's suffrage movement would bring disaster upon England are prepared to take immediate and effective action, judgement may go by default and our country drift towards a momentous revolution, both social and political, before it has realised the dangers involved."

Mary Humphry Ward argued the case against women's suffrage at debates at Newnham College and Girton College. Once a role model for educated young women, she received a hostile reception from the students when she told them that the "emancipating process has now reached the limits fixed by the physical constitution of women". She recorded in her diary after the Girton debate that "the fire and the rage were immense" and blamed the staff who she accused of being "hotly suffrage".

In an article that appeared in The Times on 27th February, 1909, Ward wrote: "Women's suffrage is a more dangerous leap in the dark than it was in the 1860s because of the vast growth of the Empire, the immense increase of England's imperial responsibilities, and therewith the increased complexity and risk of the problems which lie before our statesmen - constitutional, legal, financial, military, international problems - problems of men, only to be solved by the labour and special knowledge of men, and where the men who bear the burden ought to be left unhampered by the political inexperience of women."

The Anti-Suffrage League collected signatures against women having the vote and at a meeting on 26th March, 1909, Mary Humphry Ward announced that over 250,000 people had signed the petition. The following June she reported that the movement had 15,000 paying members and 110 branches and the number who had signed the petition had reached 320,000.

Mary Humphry Ward became editor of the organizations journal, the Anti-Suffrage Review and as well as writing a large number of articles on the subject, several of her novels, notably, The Testing of Diana Mallory (1908) and Delia Blanchflower (1915) criticised women's suffrage campaigners.

The leaders of the Anti-Suffrage League claimed that the vast majority of women in Britain were not interested in having the vote and that there was a danger that a small group of organised women would force the government to change the electoral system. 320,000.

One of the Anti-Suffrage League's main supporters was Almroth E. Wright. He argued that if women were given the vote it would lead to war: "Now it is by physical force alone and by prestige - which represents physical force in the background - that a nation protects itself against foreign interference, upholds its rule over subject populations, and enforces its own laws. And nothing could in the end more certainly lead to war and revolt than the decline of the military spirit and loss of prestige which would inevitably follow if man admitted woman into political co-partnership."

Primary Sources

(1) Report in Hansard on the speech made by William Cremer in the House of Commons on women's suffrage (25th April, 1906)

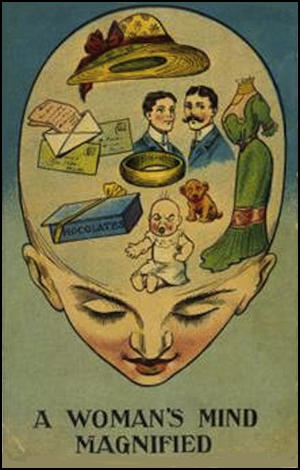

He had always contended that if we opened the door and enfranchised ever so small a number of females, they could not possibly close it, and that it ultimately meant adult suffrage. The government of the country would therefore be handed over to a majority who would not be men, but women. Women are creatures of impulse and emotion and did not decide questions on the ground of reason as men did.

He was sometimes described as a woman-hater, but he had had two wives, and he thought that was the best answer he could give to those who called him a woman-hater. He was too fond of them to drag them into the political arena and to ask them to undertake responsibilities, duties and obligations which they did not understand and did not care for.

What did one find when one got into the company of women and talked politics? They were soon asked to stop talking silly politics, and yet that was the type of people to whom we were invited to hand over the destinies of the country.

It was not only because he thought that women were unfitted by their physical nature to exercise political power, but because he believed that the majority of them did not want it and would vote against it, that he asked the House to pause before they took the step suggested by the honorable member for Merthyr Tydfil (Keir Hardie). He believed that if women were enfranchised the end would be disastrous to all political parties. He therefore asked the House to pause before it took a step from which it could never retreat.

(2) Mary Humphrey Ward, The Times (27th February, 1909)

Women's suffrage is a more dangerous leap in the dark than it was in the 1860s because of the vast growth of the Empire, the immense increase of England's imperial responsibilities, and therewith the increased complexity and risk of the problems which lie before our statesmen - constitutional, legal, financial, military, international problems - problems of men, only to be solved by the labour and special knowledge of men, and where the men who bear the burden ought to be left unhampered by the political inexperience of women.

(3) An Anti-Suffrage Society was formed in East Grinstead in May 1911. A report of the meeting was published in the East Grinstead Observer on 27th May 1911.

There was a large attendance at a "At Home" held at Hurst-on-Clays, East Grinstead, by kind permission of Lady Jeannie Lucinda Musgrave on Tuesday afternoon. Mrs. Archibald Colquhoun of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League said that women had never possessed the right to vote for Members of Parliament in this country nor in any great country, and although the women’s vote had been granted in one or two smaller countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, no great empire have given women’s a voice in running the country. Women have not had the political experience that men had, and, on the whole, did not want the vote, and had little knowledge of, or interest in, politics. Politics would go on without the help of women, but the home wouldn’t.

The speaker also stated that in a recent canvas by postcard, of the 200 odd women in East Grinstead, they found that 80 did not want the vote, 40 did want the vote and the remainder would not sufficiently interested in replying.Lady Musgrave, President of the East Grinstead branch of the Anti-Suffragette League said she was strongly against the franchise being extended to women, for she did not think it would do any good whatsoever, and in sex interests, would do a lot of harm. She quoted the words of Lady Jersey: "Put not this additional burden upon us." Women were not equal to men in endurance or nervous energy, and she thought she might say, on the whole, in intellect.

(4) A meeting of the Anti-Suffrage Society was reported in the East Grinstead Observer on 3rd June 1911.

There was a large attendance – chiefly of ladies – at the Queen’s Hall on Friday afternoon, where there was a debate on Women’s Suffrage. Mr. Charles Everard presided. Mr. Maconochie spoke against the extension of the franchise to women. Mr. Maconochie was opposed to suffrage because there were two many women to make it safe. There were 1,300,000 more women than men in the country, and he objected to the political voting power being placed in the hands of women.

(5) Almroth E. Wright, The Times (April, 1912)

The woman of the world will gaily assure you that of course half the women in London have to be shut up when they come to the change of life ... no doctor can ever lose sight of the fact that the mind of woman is always threatened with danger from the reverberations of her physiological emergencies. It is with such thoughts that the doctor lets his eyes rest upon the militant suffragist. He cannot shut them to the fact that there is mixed up with the woman's movement much mental disorder.

(6) Almroth E. Wright, The Unexpurgated Case Against Woman Suffrage (1913)

Now it is by physical force alone and by prestige - which represents physical force in the background - that a nation protects itself against foreign interference, upholds its rule over subject populations, and enforces its own laws. And nothing could in the end more certainly lead to war and revolt than the decline of the military spirit and loss of prestige which would inevitably follow if man admitted woman into political co-partnership.

While it is arguable that such a partnership with woman in government as obtains in Australia and New Zealand is sufficiently unreal to be endurable, there cannot be two opinions on the question that a virile and imperial race will not brook any attempt at forcible control by women.

Again, no military foreign nation or native race would ever believe in the stamina and firmness of purpose of any nation that submitted even to the semblance of such control.

The internal equilibrium of the State also would be endangered by the admission to the register of millions of electors whose vote would not be endorsed by the authority of physical force.

Regarded from this point of view a Woman's Suffrage measure stands on an absolutely different basis to any other extension of the suffrage. An extension which takes in more men - whatever else it may do - makes for stability in the respect that it makes the decrees of the legislature more irresistible.

An extension which takes in any women undermines the physical sanction of the laws.

We can see indications of the evil that would follow such an event in the profound dissatisfaction which is felt when - in violation of the democratic principle that every man shall count for one, and no man for more than one - the political wishes of the large constituencies which return relatively few members to Parliament, are overborne by those of constituencies which, with a smaller aggregate population, return more members.