Helen Archdale

Helen Russel, the daughter of Alexander Russel (1814–1876) and Helen De Lacy Evans Russel (1834–1903), was born at Nenthorn, Berwickshire, on 25th August 1876, Her father was the editor of The Scotsman, who had campaigned for the entry of Sophia Jex-Blake to the medical school in Edinburgh. Her mother was one of the five women students involved in that campaign. (1)

Helen was sent to the progressive St Leonards School. Another student later wrote: "I had discovered that at St. Leonards girls were allowed to go out for walks by themselves without attendant mistresses. This spelt freedom, and it was for freedom that I thirsted. I went to my father and told him what I wanted to do. Would he help? He was at first a shade doubtful. He knew little of girls' boarding schools, but his sister Mary had been to one, and he thought she had learnt to be silly there. The girls, he understood, used to flirt with the boys at an army crammer's next door." (2)

Helen attended St Andrews University but while on holiday in Egypt met Anglo-Irish Captain (later Lieutenant-Colonel) Theodore Montgomery Archdale. In 1901 they got married and over the next few years she had a period of conformity that she later described as being "up against a wall of not dones." Over the next seven years she was an army wife and had three children, Nicholas, Alexander and Betty. (3)

Women's Social & Political Union

In September 1908, on her return from India, Helen Archdale, against the wishes of her husband, she joined the militant Women's Social & Political Union (WSPU). According to Votes for Women: "She wrote from her country home offering her time and herself simply asking where she was most needed. As a Scots woman, it was thought she accordingly went, taking part in the Scottish demonstrations and contributing £20 to expenses." (4) Apparently she was deeply impressed by a meeting with Emmeline Pankhurst. (5)

Helen Archdale took part in the Scottish suffrage demonstration on 9th October 1909, and a few days later, together with Adela Pankhurst, Maud Joachim, Catherine Corbett and Laura Evans, disrupted a meeting addressed by Winston Churchill in Dundee. (6) As Diane Atkinson explained in Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018): "Adela Pankhurst, Laura Evans and two Dundee men, Owen Clark and William Carr, had hidden themselves in an attic and threw stones, bricks and slates at the roof-light of the hall... Meanwhile, Maud Joachim, Helen Archdale and Catherine Corbett arrived by tram, leaping off to create a stir of surprise, and gathering a friendly crowd to storm the barricades thrown up around the hall... The police grabbed the suffragettes and locked them in the basement." (7)

Votes for Women reported: "Miss Joachim and Mrs Archdale were dragged through the barricades, and hidden in a basement by the police. The crowd tried to rescue them several times on the way to the police station, clapping and cheering and shouting, "Votes for women!" Meanwhile in the little dark room where the other two women had been hidden. Miss Adela Pankhurst, kneeling below the sill, shouted 'Votes for women!' This was immediately answered by a volley of slates from the stewards and much bad language." (8)

Helen Archdale, Adela Pankhurst, Maud Joachim, Catherine Corbett, and Laura Evans were charged with breach of the peace. All the women made a lengthy speech in court but they were all found guilty and sentenced to ten days in prison. They immediately went on hunger-strike. A telegram sent on 21st October from the Under Secretary from Scotland said "Dundee prisoners should unless medically certified unfit be fed under medical supervision if and when necessary." A prison medical officer determined that Archdale and Corbett, who were older, were not suitable for force feeding and Adela was mentally "peculiar" and fragile. On the 24th October, medical officers reported that all five women should be released, including "Miss Evans, who has given no trouble or anxiety whatever and also looks very well" on the grounds that it (force feeding) would expose her to a mental strain of an unjustifiable nature." (9)

In September 1909, imprisoned members of the Women's Social & Political Union (WSPU), Mary Leigh, Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth, Mabel Capper, Patricia Woodcock and Rona Robinson had been imprisoned in England who went on hunger-strike were forced-fed. (10) Scotland decided to take a different approach and after the women refused to take food for 102 hours, no attempt was made to feed them forcibly, and they were all released after four days. (11)

Early in 1910 Helen Archdale became the Sheffield organizer of the WSPU. The following year she moved to London and became the prisoners' secretary of the union. (12) In December 1911 she was involved in a window-breaking campaign in the West End. "The first prisoners to be tried were Evelyn Taylor, aged 34, Helen Archdale, aged 35, Aileen Connor Smith, aged 28, described as a gardener, and Violet Hudson Harvey, aged 25, all of whom were charged with maliciously damaging plate-glass windows at the Grand Hotel buildings, Charing Cross, to the amount of £100. The jury, after a retirement of six minutes, returned a verdict of 'Guilty' against all four prisoners. The Judge said it would be useless to bind them over if they would not promise to keep within the law, and it was a grief to him to have to pass sentence of two months' imprisonment in the second division in each case in order to protect the unfortunate citizens who had suffered." (13)

Suffragette Newspaper

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." (14)

As a result of this expulsion, the Women's Social & Political Union lost control of Votes for Women. They now published their own newspaper, The Suffragette. Initially, the circulation of the newspaper was about 17,000. In October 1912 Helen Archdale began working in various capacities on the new WSPU's newspaper. Here she gained compositing and editing skills that would prove useful later. (15)

First World War

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (16)

Christabel Pankhurst wrote an article in The Suffragette where she argued: "A man-made civilisation, hideous and cruel enough in time of peace, is to be destroyed... This great war is nature's vengeance - is God's vengeance upon the people who held women in subjection... that which has made men for generations past sacrifice women and the race to their lusts, is now making them fly at each other's throats and bring ruin upon the world... Women may well stand aghast at the ruin by which the civilisation of the white races in the Eastern Hemisphere is confronted. This then, is the climax that the male system of diplomacy and government has reached." (17)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. (18)

Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (19) In another interview she stated: "We suffragists... do not feel that Great Britain is in any sense decadent. On the contrary, we are tremendously conscious of strength and freshness." (20)

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!". (21)

In October 1915, The WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Helen Archdale remained loyal to the WSPU and was willing to work for the new journal. (22) Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom". The newspaper attacked politicians and military leaders for not doing enough to win the war. In one article, Christabel Pankhurst accused Sir William Robertson, Chief of Imperial General Staff, of being "the tool and accomplice of the traitors, Grey, Asquith and Cecil". Christabel demanded the "internment of all people of enemy race, men and women, young and old, found on these shores, and for a more complete and ruthless enforcement of the blockade of enemy and neutral." (23)

Helen Archdale also started a training farm for women agricultural workers. She also served as a clerical worker with Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps from. Later she became Lady Clerk at the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) headquarters. The following year in 1918 worked in the women's department of the Ministry of National Service. During this period she left her husband, Theodore Montgomery Archdale. (24)

In 1918 Helen Archdale became assistant to Margaret Haig Thomas, the head of the Ministry of National Service, dealing with correspondence, card indexing and contacting and classifying details of women available for naval, military and air service. After the death of her husband, Archdale became Margaret's personal secretary. Archdale's three children were boarding at Bedales School and Margaret was paying their school fees. Elizabeth Robins suggested that the two women had become lovers. (25)

David Alfred Thomas suffered poor health throughout his life and survived six attacks of rheumatic fever. In 1917 a heart specialist diagnosed angina. His doctor told him he could live until he was ninety if he slowed down and took care. This he refused to do and when in June 1917 David Lloyd George, offered him the post of minister of food control, he accepted. He travelled huge distances and addressed numerous meetings. Thomas was promoted to the rank of Viscount and the prime minister explained the King had agreed "that the Remainder of your peerage should be settled upon your daughter". Viscount Rhondda died on 3rd July 1918. (26)

As Deirdre Beddoe pointed out: "Margaret was left an extremely wealthy woman. Lord Rhondda's estate was valued at £885,645: she inherited his property, his commercial interests, and his title. Margaret inherited his property, his commercial interests, and his title. The Directory of Directors for 1919 listed Viscountess Rhondda, as she now was, as the director of thirty-three companies (twenty-eight of them inherited from her father) and chairman or vice-chairman of sixteen of these. Already a famous figure whose activities were widely reported in the London press on account of her business career and of her increasingly leading role as a spokeswoman for feminism." (27)

Time and Tide

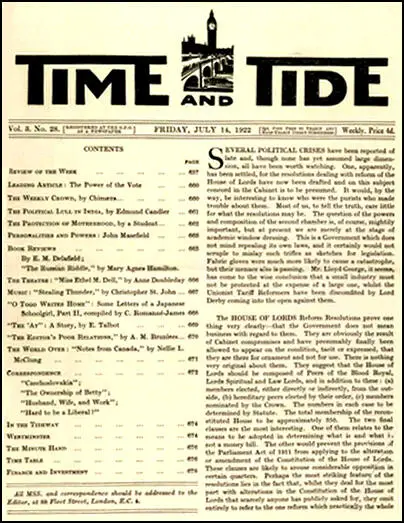

Margaret Haig Thomas decided to use some of her wealth to publish the feminist political magazine Time and Tide. Helen Archdale became its editor. The first edition was published on 14th May 1920: "Women have newly come into the larger world, and are indeed themselves to some extent answerable for that loosening of party and sectarian ties which is so marked a feature of the present day. It is therefore natural that just now many of them should tend to be especially conscious of the need for an independent press, owing allegiance to no sect or party. The war was responsible for breaking down the barriers which kept each individual or group of individuals in a watertight compartment. The past five years have taught the importance of that wider view which sees the part in relation to the whole. There is another need in our press of which the average person of today is conscious, but which must specially weigh with women - the lack of a paper which shall treat men and women as equally part of the great human family, working side by side ultimately for the same great objects by ways equally valuable, equally interesting; a paper which is in fact concerned neither specially with men nor specially with women, but with human beings." (29)

Its masthead included a drawing of the tidal River Thames below the House of Parliament and Big Ben. This signified the magazine's interest in Westminster politics. Margaret wanted it to have a similar impact to the New Statesman. She hoped it would "mould the opinion" not of the masses but of what she called "the keystone people", the vanguard who in turn would influence and guide the many. (30)

According to Deirdre Beddoe: "Time and Tide was for Lady Rhondda the fulfillment of a childhood dream. It was her grand passion, to which she devoted all her energies, at the expense of her business interests and her health. Though it was nominally owned by a limited company (the Time and Tide Publishing Company) and incorporated with £20,000 capital, Lady Rhondda subsidized the journal from the outset. She controlled 90 per cent of the shares, was at first vice-chairman, then chairman of directors." (31)

Lady Rhondda believed that the major problem that women faced was the scale of the prejudice which fuelled the opposition to attempted reforms. She maintained that after the war the women's movement was engaged in two battles, to achieve legislative progress for women and to change public opinion. (32)

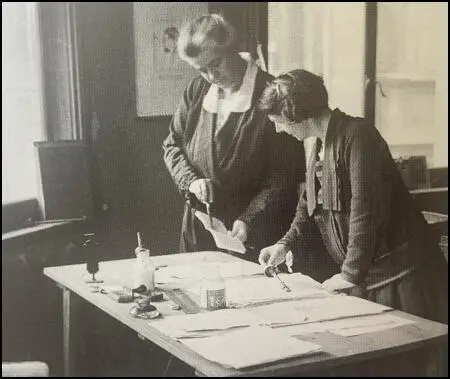

Helen Archdale (on the left) at the Time and Tide offices (c. 1922)

Time and Tide argued throughout the 1920s that it was a mistake for women to join parties while they remained so low down the political agenda. "Instead women should somehow band together as voters and force the parties to change their priorities... As the 1920s wore on it was increasingly reduced to criticising the parties for failing to place women in winnable seats and women politicians for giving excessive loyalty to their male leaders." (33)

However, she did praise the Labour Party for creating women's sections. In doing so it attracted 100,000 women members. (34) Barbara Ayrton Gould wrote: It is large; it is going to become larger; and it is new. Consider the importance of that. Men voters are still bound fast in the hoary and Tory traditions of the old-established Parties... Women... simply because they are newcomers to politics are free from this constraint." (35)

Lady Rhondda believed that "it is the strength of the non-party women's organisations rather than the number of women attached to the party organisations which is likely to decide the amount of interest taken by the parties in women's questions." (36)

Although the journal could be described as a success, it never developed into a major weapon for feminism. Lady Rhondda's critics complained that she developed an elitist strategy. At a time when 8 million women had recently obtained the vote, she showed no sign of wanting it to be read by a wide public. She later wrote she intended it to be a "first-class review" that was "read by comparatively few people, but they are the people who count, the people of influence". (37)

Six Point Group of Great Britain

In January 1921 Lady Rhondda and Helen Archdale launched the Six Point Group of Great Britain. "We have recently passed the first great toll-bar on the road which leads to equality, but it is a far cry yet to the end of the road, and our present position is not yet altogether a satisfactory one from the point of view of the country as a whole. We have, as a fact, achieved a half-way position, and that is never a position which makes for stability." (38)

Lady Rhondda argued that women were moving in the right direction yet still had some way to travel on the long road to equality, she was placing a special responsibility onto newly enfranchised women (who now constituted over a third of the electorate) to complete the task that others had started for them. (39)

The group focused on what she regarded as the six key issues for women: The six original specific aims were: (i) Satisfactory legislation on child assault; (ii) Satisfactory legislation for the widowed mother; (iii) Satisfactory legislation for the unmarried mother and her child; (iv) Equal rights of guardianship for married parents; (v) Equal pay for teachers and (vi) Equal opportunities for men and women in the civil service. (40)

The Six Point Group (SPG) was formally inaugurated on 17th February 1921. It had monthly meetings at its headquarters on the top floor of 92 Victoria Street. Other members included Ethel Annakin Snowden (vice-president), Elizabeth Robins, Cicely Hamilton, Stella Newsome, Rebecca West, Helen Archdale, Frances Balfour, Charlotte Marsh, Theresa Garnett, Winifred Mayo, Winifred Holtby and Vera Brittain. The SPG Parliamentary committee of supportive MPs was chaired by Philip Snowden. At the time there were only two women MPs: Nancy Astor and Margaret Winteringham. (41)

Helen Archdale became the international secretary of the Six Point Group. Archdale worked closely with Alice Paul in persuading the League of Nations to adopt an equal rights treaty. As Carol Miller pointed out: "At the same time, the economic depression precipitated the rise of conservative and anti-feminist policies. In this atmosphere, advances in the direction of equal rights for women became increasing difficult, particularly in the field of economic rights." (42)

The Scotsman reported in August 1929 that Helen Archdale had given an "inspiring talk". It added: "In November a big meeting is to be held to discuss the subject of the Equal Rights Treaty, an international covenant to secure international recognition of the main principles of feminism, as you will remember, this treaty was first brought forward by a handful of women, led by Alice Paul, at the Pan-American Conference at Havana last year. Never before had a woman addressed the Conference." The first article, which reads: "The contracting States agree that, upon the ratification of this treaty, men and women shall have equal rights throughout the treaty men and women shall have equal rights throughout the territory subject to their respective jurisdictions." (43)

Helen Archdale helped to establish the Equal Rights International. "Helen Archdale of Great Britain, was chosen as chairman; Jessie Street of Australia, vice chairman; Winifred Mayo, of Great Britain, hon. Sec.; Lily van der Schalk Schuster, of Holland, hon. Treasurer. The Equal Rights Treaty, which the international has been created to promote, centres round the demand that sex should be among the things in which States should consider no distinctions of rights, abate no privileges, and lessen no responsibilities." (44)

Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda

Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda had not lived with her husband Lieutenant-Colonel Theodore Montgomery Archdale for many years. Since 1918 she had lived with Helen Archdale. Lady Rhondda divorced Major Mackworth on the grounds of his desertion and misconduct in December 1922. Although she got support from many of her colleagues in the women's suffrage movement, some people criticised her for divorcing her husband. Helen Archdale's daughter Betty, claimed that a lot of Margaret's friends ostracised her as a result of her divorce. (45)

Margaret and Helen lived together in Chelsea Court. Betty Archdale pointed out that although the break-up of her marriage "hurt Margaret enormously" she "found the personal help she needed in mother". Helen admitted that she found motherhood "greatly overrated, greatly sentimentalised." The two women shared an interest in journalism and worked very closely with Time and Tide. (46)

The two women lived in London but every weekend they would travel to Chart Cottage in Watery Lane, Seal Chart, near Sevenoaks. In 1925 they moved to Stonepitts Manor House close by. (47) The house had seven bedrooms. The gardens were enclosed within high, red-brick walls and included a tennis court, rose gardens, rock gardens and a kitchen garden. The two women often had literary figures staying for the weekend: "Everyone wrote, read and talked as they liked. The result was some marvellous conversation and really gracious living." (48)

Lady Rhondda and Helen Archdale often had political disagreements and increasing editorial interventions, resulted in her being effectively forced out of the editorship of Time and Tide in 1926. Although she remained a director of Time and Tide Publishing Company, "after her resignation specifically feminist concerns were gradually marginalized in" the magazine. (49)

Although the two women continued to live together the relationship was in difficulty. In a letter written in November, 1926, Margaret commented: "I don't know whether you ever ask yourself why we live together; if you ever go back to the time when we first came together. We began it for the only reason that can make living together possible, because we were very fond of one another. I have paid heavily for believing that your love, that seemed a real thing, was real - when in fact it can only have been a passing surface passion, much as I've seen you several times. I gave all I had to give and for years now I have been struggling not to see, what you were making only abundantly clear, that the only value I had in your eyes was as some one who could give the children treats." (50)

The two women continued to live together but Lady Rhondda resented the fact that she was paying all the bills: "I very much dislike spending a lot of money when I am already living beyond my income as I am these bad years". (51) They still spent times together at Stonepitts Manor House but as Helen explained to a friend "we do not necessarily go together in fact it is rarely that we coincide." It was not until the spring of 1931 that Helen left the house for good. (52)

Later Years

Helen Archdale was active in the International Federation of Business and Professional Women. She also contributed to The Times, The Daily News and The Scotsman. Her daughter Helen Elizabeth (Betty) Archdale served in the Women's Royal Naval Service in the Second World War and later became principal of the women's college in the University of Sydney, Australia. (53)

Helen Archdale was active in the Suffragette Fellowship. (54) It was established by Edith How-Martyn and Una Dugdale in 1926 to "perpetuate the memory of the pioneers and outstanding events connected with women's emancipation and especially with the militant suffrage campaign, 1905-14, and thus keep alive the suffragette spirit". The Suffragette Fellowship undertook to create a formal archive and a "Woman's Record Room" was established in the Minerva Club. The Committee of the Record Room included Helen Archdale, Edith How-Martyn, Winifred Mayo, Charlotte Marsh, Theresa Garnett, Sophia Duleep Singh, Minnie Baldock, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Ada Flatman, Mary Gawthorpe, Rachel Barrett, Margaret Haig Thomas, Teresa Billington-Greig and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. (55)

Helen Archdale died at 17 Grove Court, St John's Wood, on 8th December 1949.

Primary Sources

(1) The Dundee Courier (18th October 1909)

Their sudden appearance (Catherine Corbett, Maud Joachim and Helen Archdale) had a magical effect on the mob. Surging round the women, they threw themselves against the solid wall of police. The officers fought valiantly, but were utterly helpless to stem the great human tide… Meanwhile the crowd time and again charged the police, and succeeded in reaching the barricades… The crowd in Reform Street were now incensed to fever pitch, and several ugly rushes were made to force a way to Bank Street.

(2) Votes for Women (29th October 1909)

Mrs Archdale, a Scots woman, and a daughter of Mr Russel, founder of the Scotman, heard the call of the movement from afar. She wrote from her country home offering her time and herself simply asking where she was most needed. As a Scots woman, it was thought she accordingly went, taking part in the Scottish demonstrations and contributing £20 to expenses. Mrs Archdale offered herself especially for the protest at Dundee. Her mother was one of the first women doctors, and she was herself a graduate of a Scottish University. (June 29)

(3) Votes for Women (29th October 1909)

Mrs Corbett, Miss Joachim, and Mrs Archdale led the "rushes" waving the colours and shouting "Votes for women!"; "Down with the barricades"; "Rush the Barricades"; "Follow me, men!" They all came, and there was a furious melee of crowd, police and mounted police.

Miss Joachim and Mrs Archdale were dragged through the barricades, and hidden in a basement by the police. The crowd tried to rescue them several times on the way to the police station, clapping and cheering and shouting, "Votes for women!"

Meanwhile in the little dark room where the other two women had been hidden. Miss Adela Pankhurst, kneeling below the sill, shouted "Votes for women!" This was immediately answered by a volley of slates from the stewards and much bad language.

Brickbats and slates came flying from the roof, but regardless of these dangers, Miss Evans and Miss Pankhurst stretched out of the window, throwing everything that came to hand of a light nature, including two 2lb. weights attached to strings, which though excellent for breaking glass, could not fall through and hurt anyone.

(4) Helen Archdale, Votes for Women (29th October 1909)

I was hungry during the whole four days and suffered a great deal from headache and cramp. I protested against wearing the prison clothes, but found resistance useless. I am determined to go on with militant protests until the Government grants the just demand of women.

(5) Dundee Advertiser (25th November 1909)

The five suffragettes who were sentenced to terms of ten days' imprisonment in connection with the rioting at Mr Churchill's meeting last Tuesday evening were liberated yesterday. They were over four days in prison - or 102 hours in all - and during that time refused to take any food. No attempt was made to feed them forcibly, as has recently been done in the case of other hunger strikers in England.

The release was made on the order of the Secretary for Scotland and came as a welcome relief to the friends of the "martyrs".

(6) The Yorkshire Evening Post (12th December 1911)

Mr. R. Wallace, K.C. began the hearing, at London Sessions today, of the charges arising out of the window-breaking tactics of the suffragists in the West End several weeks ago. All the prisoners came prepared for eventualities. Some carried large bags, others had luncheon baskets, while many appeared with impediments in the shape of clothing.

The first prisoners to be tried were Evelyn Taylor, aged 34, Helen Archdale, aged 35, Aileen Connor Smith, aged 28, described as a gardener, and Violet Hudson Harvey, aged 25, all of whom were charged with maliciously damaging plate-glass windows at the Grand Hotel buildings, Charing Cross, to the amount of £100.

The jury, after a retirement of six minutes, returned a verdict of "Guilty" against all four prisoners…

The Judge said it would be useless to bind them over if they would not promise to keep within the law, and it was a grief to him to have to pass sentence of two months' imprisonment in the second division in each case in order to protect the unfortunate citizens who had suffered.

The prisoners received the sentence with a bow.

(7) Margaret Haig Thomas, letter to Helen Archdale (10th November, 1926)

I don't know whether you ever ask yourself why we live together; if you ever go back to the time when we first came together. We began it for the only reason that can make living together possible, because we were very fond of one another. I have paid heavily for believing that your love, that seemed a real thing, was real - when in fact it can only have been a passing surface passion, much as I've seen you several times. I gave all I had to give and for years now I have been struggling not to see, what you were making only abundantly clear, that the only value I had in your eyes was as some one who could give the children treats. And even though that was my own role of value you shut me always and persistently outside the family circle and taught the children to do the same - one was allowed as a hanger-on - because one was useful - but no more. When I tried to tell you I cared, you sneered. I imagine you despised me because I was too ready to give - but you see you had been ready enough at first and I couldn't believe for a long while that you had changed.... I imagine the end cannot be very far off now. To live together is possible only when people love each other. These last few weeks with the queer calm we are keeping on the surface, can't last.

(8) The Daily News (1st October 1927)

Wisely sensible to the value of environment, in 1877 a group of men and women started St Leonards School. In 1877, St Andrews was not easily accessible, but herself needed no outside attraction. Beautifully situated, the whole city is a storehouse of romance and historical memories, saints and martyrs, political and religious, queens and cardinals have crossed her stage.

Making history in their turn, these brave pioneers, inspired by women when, having themselves won who, having themselves won education, wished to make the path for their successors, formed a company. Their capital was £700; their premises, one house plus one garden; their staff, a headmistress and five assistants.

(9) The Scotsman (9th August 1929)

Recently I had a talk with Mrs Helen Archdale, international secretary of the Six Point Group. It was an inspiring talk. In November a big meeting is to be held to discuss the subject of the Equal Rights Treaty, an international covenant to secure international recognition of the main principles of feminism, as you will remember, this treaty was first brought forward by a handful of women, led by Alice Paul, at the Pan-American Conference at Havana last year. Never before had a woman addressed the Conference…

The treaty is simplicity itself. All that matters is contained in the first article, which reads: "The contracting States agree that, upon the ratification of this treaty, men and women shall have equal rights throughout the treaty men and women shall have equal rights throughout the territory subject to their respective jurisdictions."

"A big idea? Of course, its big!" said Mrs Archdale. "But we feminists are not a body afraid of being laughed at. We know what we want, and that ultimately, we shall get it."

(10) Reynolds Illustrated News (1st February 1931)

The report, just issued, of work done by the Six Point Group during the 1930s tells the story of the formation of the Equal Rights International. A numerous delegation representing various organisations of women from Great Britain and the Dominions sat at Geneva during the whole period of the Eleventh Assembly. "It quickly became clear," says the Report, "that no national organisation could effectively carry on work of such a widely international character as required by the Equal Rights Treaty."

The Treaty had to have the support within the League of all States members, therefore any organisation seeking that support must have within itself a similarly representative membership. It was therefore decided to form a new organisation. Helen Archdale of Great Britain, was chosen as chairman; Jessie Street of Australia, vice chairman; Winifred Mayo, of Great Britain, hon. Sec.; Lily van der Schalk Schuster, of Holland, hon. Treasurer. The Equal Rights Treaty, which the international has been created to promote, centres round the demand that sex should be among the things in which States should consider no distinctions of rights, abate no privileges, and lessen no responsibilities.

(11) Carol Miller, Inter-War Feminists and the League of Nations (1994)

The proposal for an equal rights treaty originated in July 1926 with Lady Margaret Rhondda, editor of Time and Tide and chair of the British Six Point Group, an equal rights organisation formed in 1921. Rhondda was convinced that most valuable propaganda could be done in the course of demanding an equality convention. A member of the International Advisory Committee of the American National Woman's Party, she wrote directly to its chair, charismatic lawyer Alice Paul, about the plan. The idea could not fail to appeal to the the shrewd calculating mind that had conceived the American Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Following the model of the ERA, Paul drafted an equal rights treaty. It had only one effective clause: The contracting States agree that upon the ratification of this Treaty, men and women shall have Equal Rights throughout the territory subject to their respective jurisdictions. For the next decade Paul spent most of her time outside the US attempting to sell the treaty to feminists, the Pan-American Union, the League of Nations and the International Labour Office (ILO).

The Woman's Party support for an equality convention can be interpreted in part as a conscious manoeuvre to help persuade the American Congress to pass the ERA. Members believed that if other countries signed such a convention the US, for reasons of international prestige, would be obliged to follow suit, if not by signing an equal rights treaty, then at least by passing the ERA to signal their support for the principle of equality. By the late 1920s equal rights feminists in both the US and Britain had reached a sort of impasse. In the years immediately following the war, many legal inequalities had been overcome yet discrimination still existed in civil and labour law. Social reform and working women's organisations were promoting further legal inequalities through protective labour legislation for women. At the same time, the economic depression precipitated the rise of conservative and anti-feminist policies. In this atmosphere, advances in the direction of equal rights for women became increasing difficult, particularly in the field of economic rights. To counter the incremental and, in their view, even regressive pattern of change at the national level, equal rights feminists turned to Geneva as The Key to Equality. As British pacifist and feminist Vera Brittain put it, the time has now come to move from the national to the international sphere, and to endeavour to obtain by international agreement what national legislation has failed to accomplish.

(12) The Daily News (19th August 1949)

Among the 40 members of the Suffragette Fellowship who paid a visit to "Anne Veronica" yesterday afternoon and then took tea with Wendy Hiller, was Mrs Helen Archdale, who is aged 73, and whose son Alexander is now playing in "The Schoolmistress" at the Arts Theatre.

Her son says she was a "great window-breaker in her day". For her enterprise on behalf of the cause she spent some time as a guest of his Majesty at Holloway Prison.

Mrs Archdale has just returned from Australia, where she has been visiting her daughter, now principal of a woman's college in Sydney.