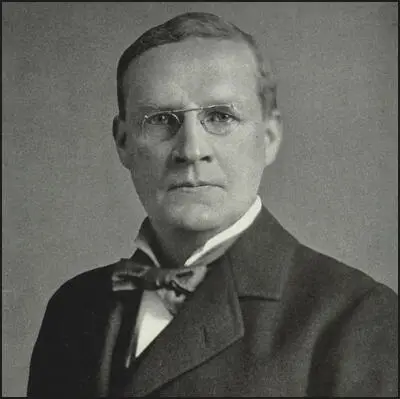

David Alfred Thomas

David Alfred Thomas, the son of Samuel Thomas (1800–1879), a Merthyr shopkeeper and his second wife, Rachel Thomas, the daughter of the mining engineer, Morgan Joseph, was born in Ysgyborwen, near Aberdare, on 26th March, 1856. David was the fifteenth of seventeen children. (1) Tragically only five of their children survived infancy. Samuel Thomas was close to bankruptcy at the time of his son's birth, and it is claimed he said, "I see nothing for him but the workhouse." (2)

However, he eventually became a successful mining entrepreneur and became the senior partner in Thomas and Davey, a company based in Cardiff that owned several collieries in the Rhondda Valley. This enabled him to send David to a private school at Clifton. Thomas studied mathematics at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, and was awarded a BA in 1880. "Much of his time at college was spent on boxing, sculling, and rowing; but he must have devoted some time to study, for, whereas most businessmen of the time merely practised the precepts of capitalist economics intuitively, Thomas had actually read the texts." (3)

On the death of his father in 1879 he inherited a personal fortune of £75,000, Ysguborwen Colliery and a share in the Cambrian Colleries. The following year David met Sybil Haig a talented artist and painted miniatures and later exhibited some of her work in London galleries. Sybil had an impressive extended family with a long history proudly traced back to Petrus De Haga of the 12th century. Her father George Haig became a successful agent in England for the sale of Scotch and Irish spirits. In 1858 he purchased 2,548 acres of land with eleven farms near the village of Llanbadarn Fynydd, between Llandrindod Wells and Newtown. In 1862 he designed and had built Pen Ithon Hall. Haig became High Sheriff for the county as well as a magistrate. (4)

House of Commons

Despite the objections of her father, David and Sybil got engaged in July 1881. (5) On 27 June 1882, the couple married. In 1888 Thomas became the Liberal MP for Merthyr Tydfil. Her husband's political career meant that she spent much time in London but their main home was a large house and estate at Llanwern, Monmouthshire. A daughter, Margaret Haig Thomas was born at Princes Square, Bayswater, on 12th June 1883. (6) Margaret later wrote: "My father was disappointed: he wanted a boy". (7)

In June 1890 Thomas joined forces with David Lloyd George in a campaign to bring an end to church tithes. There "was a predicable howl of outrage from the Welsh Nonconformist press." This was against the official Liberal Party policy and by voting against the party whip and justifying his rebellion with a coherent argument, Thomas "had made an early declaration of independence." (8)

Thomas did not develop a successful political career in the House of Commons. "The explanation for this may be that he was said to be a poor speaker and tended to make enemies by arguing too much in the press. Also, the effect of his role in Welsh politics was ambiguous. An initial enthusiast, he was a whip in a loose 'Welsh parliamentary party' in 1888 and 1892, and one of four Welsh rebels who refused the Liberal whip in 1894." (9)

Thomas pointed out that during the previous quarter of a century, there had been fourteen years of Liberal government - and not one bill dealing with Wales's national interests. In 1895 Thomas proposed new legislation that would exclude Welsh bishops from the House of Lords, made tithes payable to county councils, which would be given the duty of distributing them to worthy institutions, and placed burial grounds in the care of local authorities. The leader of the Liberal Party, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, objected to the idea on the grounds that it was pointless spending hours debating a bill which the House of Lords was bound to reject. (10)

The Daily News reported that "No one looking at Mr. D. A. Thomas M.P. would associate him, even in thought, with political incendiarism. No one reading the limited story of his gentle life would conclude that he could lead a revolt, or even join in one, against a black beetle… Yet, here is this gentlemanly, highly-educated Welsh colliery-owner formally turning his back upon the Government, and spurning their Whips… David Alfred Thomas is a good-looking young man of 36. His manners are fall of response, suggesting a goodly reserve of force and plenty of self-possession… But, then, it may be said that the Welsh Radical members are all not what they seem." (11)

In 1898 Thomas, rather than David Lloyd George, was elected as leader of the Welsh Liberals. Lloyd George, who had withdrawn from the contest, told his friends that he could have won it, but the "jealousy" of some South Wales men would have split the party. He said he would rather "dig potatoes" than preside over such a group. Besides, he said, Thomas "was nice man" and was amenable to suggestions from Lloyd George. However, this was not the case and Thomas refused to convert the Welsh parliamentary party into a political machine. (12)

At the 1906 General Election the Liberal Party won 397 seats (48.9%) compared to the Conservative Party's 156 seats (43.4%). The Labour Party, led by Keir Hardie did well, increasing their seats from 2 to 29. In the landslide victory the Tory leader, Arthur Balfour lost his seat as did most of his cabinet ministers. Margot Asquith wrote: "When the final figures of the Elections were published everyone was stunned, and it certainly looks as if it were the end of the great Tory Party as we have known it." (13) The new Prime Minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman failed to appoint Thomas to a cabinet post. (14)

Campbell-Bannerman suffered a severe stroke in November, 1907. He returned to work following two months rest but it soon became clear that the 71 year-old prime minister was unable to continue. On 27th March, 1908, he asked to see H. H. Asquith. Asquith's wife pointed out: "Henry came into my room at 7.30 p.m. and told me that Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman had sent for him that day to tell him that he was dying... He began by telling him the text he had chosen out of the Psalms to put on his grave, and the manner of his funeral... Henry was deeply moved when he went on to tell me that Campbell-Bannerman had thanked him for being a wonderful colleague." (15)

D. A. Thomas and the Coal Industry

D. A. Thomas consistently topped the poll, not even Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, who stood against him in the 1900 General Election, was able to topple him from his perch. Although a major employer in the area, he was felt to be a fair man, and was genuinely respected by the voters of Merthyr Tydfil. However, he was disappointed by not being appointed to office he decided not to stand in the 1910 General Election. (16)

Thomas now renounced politics and turned to business. Within a few years he controlled a dozen colliery undertakings, representing over a fifth of the national coal output (52 million tons), together with their sales agencies. "During these years Thomas followed two broad strategies: vertical integration of pits through a holding company, and forward integration into marketing and distribution. He also extended his activities across the Atlantic and acquired numerous local directorships and, significantly, newspapers." (17) Brinley Thomas has argued: "The amassing of a fortune was to be the substitute for the prizes of politics, and in a few years a series of shrewd deals led to the establishment of the Cambrian Combine with a capital of £2,000,000." (18)

The New York World reported: "If you should seek in Great Britain, the type of the American captain of industry you'd find your man in David Alfred Thomas. If you should be curious to know what measure of material success may come to a man born rich, bred at an aristocratic university, conspicuous in politics and society, and with an ambition to make the world his market-place, inquire into the career of David Alfred Thomas. In England they call David Alfred Thomas the "Welsh Coal King". Within the past eight years he has become the active head of collieries in South Wales at which 50,000 men find employment, and whose employment, and whose output exceeds more than one-quarter the production of the entire field." (19)

Thomas had grandiose plans of Anglo-American industrial combinations and the opening up of the remote northwest of Canada. As creator and controller of the largest coal combine in the region D. A. Thomas clashed with the South Wales Miners' Federation. The main issue at stake, payment for work, was intimately related to the tussle over a minimum wage. Thomas claimed in 1910 that "the machine has been captured by young socialists of immature judgement". (20)

Women's Suffrage

D. A. Thomas' wife, Sybil Haig Thomas and his daughter, Margaret Haig Thomas, were supporters of women's suffrage and were both members of the militant Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). Margaret admired her cousins and aunts who had gone to prison during the struggle for women's suffrage. This included Florence Haig, Evelyn Haig, Cecilia Wolseley Haig, Janet Haig Boyd and Charlotte Haig. Margaret suggested that prison for Florence was a pastime: she went "at such intervals as she could afford to spare from her own trade of portrait painting" and that Janet "went most regularly, never less than once a year." Margaret claimed that Janet insisted on greeting each clergyman with "How do you do - I've just come out of prison." (21)

Margaret Haig Thomas gradually became convinced that women had to increase its militant activity if they were to obtain the vote. This included disrupting postal deliveries. In December, 1911, Emily Wilding Davison, set fire to three pillar boxes in Parliament Street in London. She was arrested and sentenced to six months in prison. This began a long campaign where Britain's 50,000 pillar boxes were targeted. On one weekend in March 1913 there were fourteen attacks on letter boxes in Cardiff alone. (22)

Laurence Housman revealed in his autobiography, The Unexpected Years (1937) that Margaret confessed to him about setting fire to pillar boxes when he was staying with D. A. Thomas and Sybil Haig Thomas: "At dinner the increase of militancy was being discussed, and, in certain of its forms, condemned. Only that week a local letter box had been set on fire; it was the latest form that militancy had then taken; and in that high social circle it was not approved: it was hoped that the perpetrators would be caught and punished. My host's daughter was sitting next to me: she gave me a soft nudge. 'I did it', she said." (23)

In December 1912 there were several local newspaper reports of Newport's pillar boxes being attacked. The glass tubes containing acid were labelled "Votes for Women". The following year Margaret Haig Thomas visited the Women's Social & Political Union headquarters in London. She was given twelve long glass tubes with corks. Six contained phosphorous and the other six held a chemical compound. When mixed together they produced flames. "She travelled home in a crowded third-class railway compartment with her incendiary materials in a flimsy covered basket on the seat beside her." (24)

On 25th June, 1913, she placed two of the tubes in a foolscap envelope and took a tram for the five-mile journey to Newport. "My heart was beating like a steam engine, my throat was dry, and my nerve went so badly that I made the mistake of walking several times backwards and forwards past the letter box before I found the courage to do it... I smashing them on the inside edge of the letter box as one let them drop. It looked to other passers-by exactly as if one were posting a letter." (25)

Within a few minutes, smoke could be seen coming from the letter box. Water from a nearby house was used to extinguish the smoke and flames and a postman saved some of the letters. The next day, as she was on her way from her house to a tea party in Llanwern village, Detective-Sergeant Caldecott and Police Constable King arrested her and took her to the police station. Margaret was locked in a cell with a wall covered in vomit. It smelt like a urinal. She remained there for over four hours until her husband arrived to pay £100 bail money. (26)

Margaret's trial took place on 11th July, 1913. Margaret pleaded "Not Guilty" as the WSPU required but "made no special effort to pretend that I had not done the thing". (27) It was argued in court that the contents of the tube had been prepared "by a chemist of exceedingly great ability" and it damaged eight letters and five postcards. Margaret was found guilty and fined £10 plus 10s costs. Margaret refused to pay her fine or allow others to pay for her and she was sentenced to a month in the county gaol at Usk. (28)

Margaret went on hunger-strike. "I had made up my mind that I would not touch food whilst I was in prison. I had further decided that in order to hurry on the time when I should be weak enough to be let out I would refuse drink for as long as I could; but would take it if and when I found my thirst unendurable... I did not feel particularly hungry, but I did get terribly thirsty. By the end of three days I had reached the stage where I had difficulty in restraining myself from drinking the contents of the slop pail." The authorities were concerned about her health and released her on the sixth day under the terms of the Cat & Mouse Act. (29)

On the day that her licence expired Margaret Haig Thomas fine was mysteriously paid. It has been assumed, but never proved, that her husband paid the money. On the same day an inaugural meeting of a branch meeting of the Church League for Women's Suffrage was held in a local hall. Sybil Haig Thomas was one of the organisers. Margaret attended and, according to the press "seemed to be quite recovered from the effects of her hunger strike."When asked about the payment, she replied that the fine had been paid contrary to her wishes. (30)

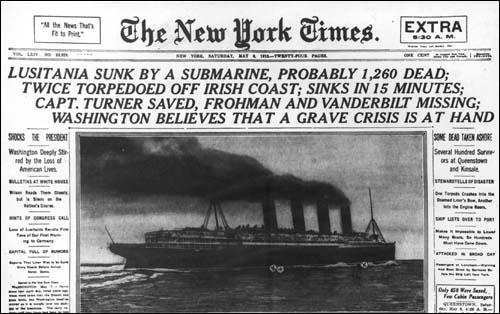

Sinking of Lusitania

In March 1915, Thomas went on a seven-week business trip with his daughter, Margaret to New York. They both decided to come home on the Lusitania, the largest and fastest passenger ship in commercial service. It was 750ft long, weighed 32,500 tons and was capable of 26 knots. It left New York harbour for Liverpool on 1st May, 1915. However, it was going to be a dangerous journey. (31)

On 4th February, 1915, Admiral Hugo Von Pohl, sent a order to senior figures in the German Navy: "The waters round Great Britain and Ireland, including the English Channel, are hereby proclaimed a war region. On and after February 18th every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without its always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening. Neutral ships will also incur danger in the war region, where, in view of the misuse of neutral flags ordered by the British Government, and incidents inevitable in sea warfare, attacks intended for hostile ships may affect neutral ships also." (32)

Soon afterwards the German government announced an unrestricted warfare campaign. This meant that any ship taking goods to Allied countries was in danger of being attacked. This broke international agreements that stated commanders who suspected that a non-military vessel was carrying war materials, had to stop and search it, rather than do anything that would endanger the lives of the occupants. This message was reinforced when the German Embassy issued a statement on its new policy: "Travellers intending to embark for an Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that in accordance with the formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain or any of her allies are liable to destruction in those waters; and that travellers sailing in the war zone in ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk." (33)

Most of the passengers were aware of the risks they were taking. Margaret Haig Thomas later recalled that in New York City during the weeks preceding the voyage "there was much gossip of submarines". It was "stated and generally believed that a special effort was to be made to sink the great Cunarder so as to inspire the world with terror". On the morning that the Lusitania set sail the warning that had been issued by the German Embassy on 22nd April 1915, was "printed in the New York morning papers directly under the notice of the sailing of the Lusitania". Margaret commented that "I believe that no British and scarcely any American passengers acted on the warning, but we were most of us very fully conscious of the risk we were running." (34)

At 1.20pm on 7th May 1915, the U-20, only ten miles from the coast of Ireland, surfaced to recharge her batteries. Soon afterwards Captain Schwieger, the commander of the German U-Boat, observed the Lusitania in the distance. Schwieger gave the order to advance on the liner. The U20 had been at sea for seven days and had already sunk two liners and only had two torpedoes left. He fired the first one from a distance of 700 metres. Watching through his periscope it soon became clear that the Lusitania was going down and so he decided against using his second torpedo. D. A. Thomas and his daughter were just leaving the first-class dining-room when the ship was hit. (35)

William McMillan Adams was travelling with his father. "I was in the lounge on A Deck when suddenly the ship shook from stem to stem, and immediately started to list to starboard. I rushed out into the companionway. While standing there, a second, and much greater explosion occurred. At first I thought the mast had fallen down. This was followed by the falling on the deck of the water spout that had been made by the impact of the torpedo with the ship. My father came up and took me by the arm. We went to the port side and started to help in the launching of the lifeboats." (36)

D. A. Thomas became separated from his daughter when she went back to the cabin to get their lifebelts. When she returned she could not find her father. He had managed to get onto the last lifeboat that was launched. As it drew away, the ship slowly sank and the lifeboat narrowly missed being hit by its funnel. After rowing for two and a half hours a small steamer took the survivors on board. (37)

Margaret was unable to get into a lifeboat: "It became impossible to lower any more from our side owing to the list on the ship. No one else except that white-faced stream seemed to lose control. A number of people were moving about the deck, gently and vaguely. They reminded one of a swarm of bees who do not know where the queen has gone. I unhooked my skirt so that it should come straight off and not impede me in the water. The list on the ship soon got worse again, and, indeed, became very bad. Presently the doctor said he thought we had better jump into the sea. I followed him, feeling frightened at the idea of jumping so far (it was, I believe, some sixty feet normally from A deck to the sea), and telling myself how ridiculous I was to have physical fear of the jump when we stood in such grave danger as we did. I think others must have had the same fear, for a little crowd stood hesitating on the brink and kept me back. And then, suddenly, I saw that the water had come over on to the deck. We were not, as I had thought, sixty feet above the sea; we were already under the sea. I saw the water green just about up to my knees. I do not remember its coming up further; that must all have happened in a second. The ship sank and I was sucked right down with her." (38)

After about two and three quarter hours in the water before being picked up by a rowing boat. She was unconscious and at first she was presumed dead and was dumped on the deck of a small steamer called the Bluebell. Luckily a midshipment thought there was possibly "some life in this woman" and attended to her. Margaret regained consciousness at about 9.30pm. "She was lying naked wrapped in blankets on a ship's deck in the dark. Shaking violently, her teeth were 'chattering like castanets' and she felt acute back pain." However, she was in her early thirties and had a strong physique and survived the ordeal. (39) D. A. Thomas later told The Western Mail, "If I had lost her (Margaret) my life would have been blighted for ever, and everything would have become a blank for the future. She is more than a daughter to me; she is a real pal." (40)

Of the 2,000 passengers on board, 1,198 were drowned, among them 128 Americans. (41) The German newspaper Die Kölnische Volkszeitung supported the decision to sink the Lusitania: "The sinking of the giant English steamship in a success of moral significance which is still greater than material success. With joyful pride we contemplate this latest deed of our Navy. It will not be the last. The English wish to abandon the German people to death by starvation. We are more humane. we simply sank an English ship with passengers, who, at their own risk and responsibility, entered the zone of operations." (42)

Viscount Rhondda

In June 1915, David Lloyd George, Munitions Minister, asked D. A. Thomas to go to back to the United States to arrange supplies of munitions. Lloyd George explained to the House of Commons: "I felt, in consequence of the great importance of the American and Caadian markets and of the innumerable offers which I have received, directly and indirectly, to provide shell munitions of war from Canada and the United States of America, it was very desirable that I should have someone there who, without loss of time, which must necessarily take place when all your business is transacted by means of cable, should be able to represent the Munitions Department in the transaction of business there and find out exactly the position. I propose to send over, on behalf of the Munitions Department, a gentleman who was once a member of this House - a very able business man. He has business relations with America on a very considerable scale, and I propose to ask Mr. D. A. Thomas to go over to America for the purpose of assisting us in developing the American market." (43)

D. A. Thomas admitted that it was a daunting prospect as he could not ride himself of memories of the Lusitania and told Lloyd George of his fears. He replied he could not think of an efficient substitute. Less than two months after his ordeal at sea, Thomas sailed from Liverpool on the St Louis. This time, his wife, Sybil Haig Thomas, insisted on going with him. They were escorted through the danger zone by two British destroyers. On arrival in New York, he was met by the British Ambassador. He was guarded by detectives as they feared he might be assassinated by German sympathisers. Thomas was away from home for five months. (44)

In 1916, David Lloyd George appointed D. A. Thomas as the President of the Local Government Board. He found the experience frustrating as his attempts to establish a separate Ministry of Health ended in failure. (45) In March 1917 he complained of a pain in his heart. A heart specialist diagnosed angina and recommended he resign from the government and then he could live until he was ninety. (46)

Thomas did not take this advice but he did initially refuse to take the job as Minister of Food Control. Conscious of the difficulty of refusing a post in the midst of war, he took office in June 1917. (47) In this new post he worked extremely long hours in a department of 5,000 employees and his daughter later claimed he "often started work a 3 or 4 am in the morning". (48) The actions that Thomas took reduced people's food allowances. The Evening Standard commented: "No Minister has achieved the quite the same popularity as the Minister who ruthlessly cut down the people's food allowances." (49)

Just after his sixty-second birthday D. A. Thomas contracted pleurisy and spent April and May in bed or in a chair in the garden. Thomas tried to resign but the offer was refused. On 3rd June 1918, Thomas was promoted to the rank of Viscount for his service as Food Controller and King George V agreed "that the Remainder of your peerage should be settled upon your daughter... in cases where the service rendered to the State is very conspicuous". (50)

David Alfred Thomas died of heart disease and rheumatic fever on on 3rd July, 1918. David Lloyd George told a memorial service three days later that his efforts represented "one of the most distinctive triumphs of the war". (51) The Daily Telegraph declared: "When history completes its record of the leaders who baffled Prussia's ambition for the mastery of the world a distinguished place will be given to Lord Rhondda." (52) He left £20,000 to Gonville and Caius College to provide "Rhondda Scholarships." (53)

Primary Sources

(1) Margaret Haig Thomas, This Was My World (1933)

I must have been about eleven or twelve when he (D. A. Thomas) first "talked business" to me: that is, poured out a stream of description of some deal he was engaged on at the time, without any explanations - he hated explaining anything; it bored him. He walked up and down the room as he talked, turning his coins over in his pocket, and I, seated in the big armchair, listened palpitating with pride at being treated in so grown-up a fashion, but terrified of saying the wrong thing, and so showing that I was only understanding about one quarter of what he was saying, which I well knew would have instantly stopped the flood. On that occasion my mother was up in town ill, and there was no one else at home for him to talk to. He always talked business at home a great deal; he would retail every evening all that had interested him in the day's events.

(2) The Daily News (19th April, 1894)

No lone looking at Mr. D. A. Thomas M.P. would associate him, even in thought, with political incendiarism. No one reading the limited story of his gentle life would conclude that he could lead a revolt, or even join in one, against a black beetle… Yet, here is this gentlemanly, highly-educated Welsh colliery-owner formally turning his back upon the Government, and spurning their Whips…

Personally, Mr David Alfred Thomas is a good-looking young man of 36. His manners are fall of response, suggesting a goodly reserve of force and plenty of self-possession… But, then, it may be said that the Welsh Radical members are all not what they seem.

(3) David Lloyd George, speech to the House of Commons (23rd June, 1915)

I felt, in consequence of the great importance of the American and Caadian markets and of the innumerable offers which I have received, directly and indirectly, to provide shell munitions of war from Canada and the United States of America, it was very desirable that I should have someone there who, without loss of time, which must necessarily take place when all your business is transacted by means of cable, should be able to represent the Munitions Department in the transaction of business there and find out exactly the position. I propose to send over, on behalf of the Munitions Department, a gentleman who was once a member of this House - a very able business man. He has business relations with America on a very considerable scale, and I propose to ask Mr. D. A. Thomas to go over to America for the purpose of assisting us in developing the American market. He will represent and exercise the functions of the Munitions Department, both in Canada and in the United States, and he will be given the fullest authority to discharge the responsible duties with which he is entrusted. Mr. Thomas will co-operate with the representatives of the Government, both in Canada and in the United States of America. While invested with full powers, he will, no doubt, act in consultation with the authorities at home, except in cases of special urgency.

(4) The New York World (19th July 1915)

If you should seek in Great Britain, the type of the American captain of industry you'd find your man in David Alfred Thomas.

If you should be curious to know what measure of material success may come to a man born rich, bred at an aristocratic university, conspicuous in politics and society, and with an ambition to make the world his market-place, inquire into the career of David Alfred Thomas.

In England they call David Alfred Thomas the "Welsh Coal King". Within the past eight years he has become the active head of collieries in South Wales at which 50,000 men find employment, and whose employment, and whose output exceeds more than one-quarter the production of the entire field. If war had not come he would be now, probably have been one of the regents of the coal industry in the United States.

(5) Brinley Thomas, David Alfred Thomas (1959)

He was the grandson of a John Thomas, of Magor, Monmouth; born in 1770, who migrated c. 1790 to Merthyr Tydfil and became haulage-contractor to the Crawshays; he married into a yeoman family of Merthyr Vale, and had four children. Of these, the youngest, David Thomas (1811-1875), became a prominent Congregational minister at Clifton (Memoir, by his son Arnold Thomas). The eldest, Samuel Thomas (1800 - 1879), was educated at Cowbridge, became a shopkeeper at Merthyr Tydfil, but afterwards (c. 1842) turned to prospecting for coal. He married, as his second wife, Rachel, daughter of Morgan Joseph, a mining engineer of Merthyr Tydfil, and by her had seventeen children, of whom D. A. Thomas was the fifteenth, born 26 March 1856 at Ysgubor-wen Aberdare, where Samuel Thomas and his brother-in-law, Thomas Joseph, had, in 1849, opened a colliery. After his education at Dr. Hudson's School, Clifton, and Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge (B.A. 1880, M.A. 1883, Hon. Fellow 1918), D. A. Thomas went to Clydach Vale at 23 years of age to study coal mining at first hand. On 27 June 1882 he married Sibyl Margaret, daughter of George Augustus Haig, Pen Ithon, Radnorshire; they had one daughter, Margaret Haig.

In the first phase of his career (up to 1906) D. A. Thomas's real interest was politics: he topped the poll four times as Liberal Member of Parliament for Merthyr Tydfil. But success eluded him in Westminster; and when, after the 'landslide' of 1906 Campbell-Bannerman did not give him office, he was bitterly disappointed and turned all his energies to the Cambrian collieries. The amassing of a fortune was to be the substitute for the prizes of politics, and in a few years a series of shrewd deals led to the establishment of the Cambrian Combine with a capital of £2,000,000. His appetite as a capitalist and his taste for sharp polemics brought him into frequent clashes with the militant leaders of the South Wales Miners' Federation. Grandiose plans of Anglo-American industrial combinations and the opening up of the remote northwest of Canada were included in the wide sweep of his horizon as a captain of industry. Empire building in the world of business was not, however, to be his chief claim to fame. D. Lloyd George sent him on an important mission to the United States in 1915, after which he was made a peer; in December 1916 he was appointed president of the local Government Board; in June 1917 he became Food Controller. Thus D. A. Thomas came back to his first love - politics - and the unbending individualist proved himself an outstanding success as the architect of a great socialist experiment - food rationing. He died of heart failure on 3 July 1918 at his home, Llan-wern, Monmouth

Viscount Rhondda had a boyish zest for life and a remarkable capacity for managing men. His enthusiasm knew no bounds: a passion for bird-nesting which he acquired as a boy at Ysgubor-wen remained with him all his life. Apart from his towering influence on the development of the South Wales coalfield, he was not absorbed in the national life of Wales. He was a true Victorian individualist for whom life was a tournament offering glittering prizes to the enterprising. He will be chiefly remembered for his masterly administration of Great Britain's food supply in the darkest year of the First World War.

Besides his contribution on The Coal Trade to Cox, British Industries under Free Trade, 1903, D. A. Thomas published, in 1896, Some Notes on the Present State of the Coal Trade, and in 1903, The Growth and Direction of our Foreign Trade in Coal (1850-1900), which was awarded the Guy Medal of the Royal Statistical Society, and was afterwards brought down to 1913. He left £20,000 to Caius College to provide 'Rhondda Scholarships.'