Charlotte Haig

Charlotte Haig, the fourth daughter in the family of five daughters and five sons of Anne Eliza Fell (1822–1894) and George Augustus Haig (1820-1906), was born at 52 Norfolk Square, Brighton, on 25 February 1857. She was the sister of Sybil Haig Thomas and Janet Haig Boyd. (1)

Charlotte had an impressive extended family with a long history proudly traced back to Petrus De Haga of the 12th century. Her father was related to Douglas Haig who during the First World War would be promoted to the rank of Field Marshall and commander in chief of the British Expeditionary Force. (2)

George Haig became a successful agent in England for the sale of Scotch and Irish spirits. In 1858 he purchased 2,548 acres of land with eleven farms near the village of Llanbadarn Fynydd, between Llandrindod Wells and Newtown. In 1862 he designed and had built Pen Ithon Hall. Haig became High Sheriff for the county as well as a magistrate. (3)

Charlotte Haig was popular with her nieces and nephews. Margaret Haig Thomas described her as her favourite aunt. (4) After the death of her mother in 1894 she sacrificed her desire for a profession to stay at home and look after her widowed father. (5)

Women's Suffrage

George Augustus Haig died in 1906. (6) Charlotte, a member of the Liberal Party, now concentrated on her interest in politics, especially women's suffrage. One of Charlotte's cousins, Florence Haig, was an active member of the Women's Social & Political Union. On 11th February 1908, Florence and two of her artist friends, the sisters, Georgina Brackenbury and Marie Brackenbury, hid in a horse-drawn furniture van that took them to the door of the House of Commons, where they leapt out brandishing petitions. (7)

On the 30th June, 1908, she was selected to be a member of a deputation led by Emmeline Pankhurst from Caxton Hall, taking a resolution to the House of Commons demanding an immediate effective measure to give votes to women. During the procession several women were arrested. This included Florence Haig, Mary Postlethwaite, Maud Joachim, Florence Haig, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Mary Phillips, Jessie Kenney, Elsie Howey, Edith New, Mary Leigh, and Vera Wentworth. (8)

On 1st July, 1908, the women appeared in court. Mr Muskett, who appeared for the Metropolitan Police, said that there was really nothing new to be said in regard to these cases."Many ladies in the Union came there with the intention of being arrested." (9) Florence Haig said: "Mr. Asquith has shown us that peaceful demonstrations are useless." (10)

Mary Phillips argued that: "The government has forced women to adopt these tactics, and the Government is responsible for them." Elsie Howey said, "I don't think I obstructed the police, the police obstructed me." Had also a previous conviction. She had to said to a constable, "I am so glad you arrested me; I wanted to be arrested." Florence Haig was ordered to find a £20 surely or go to prison for a month. (11)

Zoe Proctor, a fellow prisoner, commented: "Miss Haig, whose hair nearly reached her ankles told me she had been given a small comb for use (in prison) which was of cause inadequate." (12) When she came out of prison she argued: "It is wonderful how each woman who acts influences her own circle. Friends who before may have been but mildly in favour, are converted into active and eager workers for the cause. Coming out is so delightful that the stupidity at the time in Holloway is forgotten." (13)

Black Friday

In January 1910, H. H. Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement". (14)

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) agreed to the idea and they declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. (15) Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated." (16)

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, when Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, requested two hours to discuss the Conciliation Bill, H. H. Asquith made it clear that he intended to shelve it. (17)

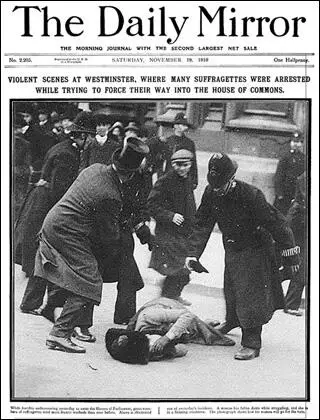

Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Pankhurst and a small group of WSPU members, were allowed into the building but Asquith refused to see them. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police. (18)

Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested during this demonstration. (19) This included Charlotte Haig, Ada Wright, Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Gladys Evans, Cecilia Wolseley Haig, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Patricia Woodcock, Vera Wentworth, Winifred Mayo, Mary Clarke, Florence Canning, Henria Williams, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Minnie Turner, Bertha Brewster, Lucy Burns and Grace Roe. (20)

Charlotte Haig was accused of hitting a police horse. She refused to accept the mounted policeman's suggestion that she head home and was taken to Scotland Yard only to be dismissed with a caution the next day. (21) Her cousin, Cecilia Wolseley Haig was not so lucky, she was badly beaten by the police and though nursed by her sister, Florence Haig, for over a year she died on 31st November 1911. (22)

Newport Branch of the WSPU

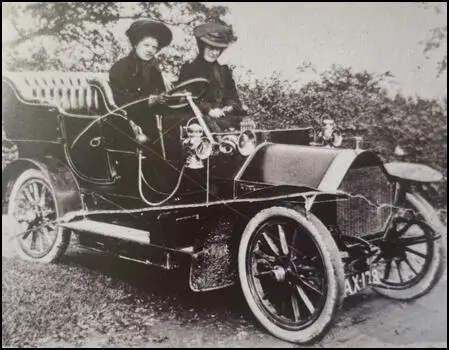

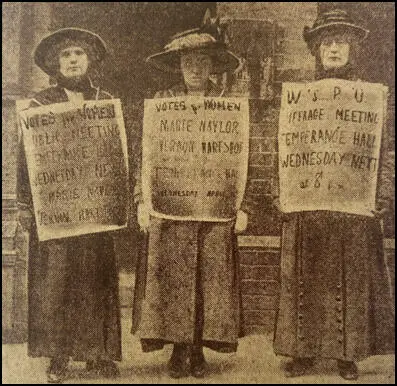

Charlotte Haig joined her neice Margaret Haig Thomas in forming a Newport branch of the Women's Social & Political Union. There is a photograph taken in 1913 showing Charlotte, Margaret and a Miss Lawson parading through Newport wearing sandwich boards advertising a WSPU meeting. (23)

In December 1912 there were several local newspaper reports of Newport's pillar boxes being attacked. The glass tubes containing acid were labelled "Votes for Women". The following year Margaret Haig Thomas visited the Women's Social & Political Union headquarters in London. She was given twelve long glass tubes with corks. Six contained phosphorous and the other six held a chemical compound. When mixed together they produced flames. "She travelled home in a crowded third-class railway compartment with her incendiary materials in a flimsy covered basket on the seat beside her." (24)

On 25th June, 1913, she placed two of the tubes in a foolscap envelope and took a tram for the five-mile journey to Newport. "My heart was beating like a steam engine, my throat was dry, and my nerve went so badly that I made the mistake of walking several times backwards and forwards past the letter box before I found the courage to do it... I smashing them on the inside edge of the letter box as one let them drop. It looked to other passers-by exactly as if one were posting a letter." (25)

Within a few minutes, smoke could be seen coming from the letter box. Water from a nearby house was used to extinguish the smoke and flames and a postman saved some of the letters. The next day, as she was on her way from her house to a tea party in Llanwern village, Detective-Sergeant Caldecott and Police Constable King arrested her and took her to the police station. Margaret was locked in a cell with a wall covered in vomit. It smelt like a urinal. Charlotte Haig offered to stand bail, but this was refused and she remained there for over four hours until her husband arrived to pay £100 bail money. (26)

Margaret's trial took place on 11th July, 1913. Margaret pleaded "Not Guilty" as the WSPU required but "made no special effort to pretend that I had not done the thing". (27) It was argued in court that the contents of the tube had been prepared "by a chemist of exceedingly great ability" and it damaged eight letters and five postcards. Margaret was found guilty and fined £10 plus 10s costs. Margaret refused to pay her fine or allow others to pay for her and she was sentenced to a month in the county gaol at Usk. (28)

Margaret Haig Thomas went on hunger-strike. "I had made up my mind that I would not touch food whilst I was in prison. I had further decided that in order to hurry on the time when I should be weak enough to be let out I would refuse drink for as long as I could; but would take it if and when I found my thirst unendurable... I did not feel particularly hungry, but I did get terribly thirsty. By the end of three days I had reached the stage where I had difficulty in restraining myself from drinking the contents of the slop pail." The authorities were concerned about her health and released her on the sixth day under the terms of the Cat & Mouse Act. (29)

On the day that her licence expired Margaret Haig Thomas fine was mysteriously paid. It has been assumed, but never proved, that her husband paid the money. On the same day an inaugural meeting of a branch meeting of the Church League for Women's Suffrage was held in a local hall. Sybil Haig Thomas was one of the organisers. Margaret attended and, according to the press "seemed to be quite recovered from the effects of her hunger strike."When asked about the payment, she replied that the fine had been paid contrary to her wishes. (30)

Later Years

Charlotte Wolseley Haig lived at Thatched Cottage, Langstone, Llanwern, near Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales. She was an amateur artist, mainly painting landscapes. In 1924-25 she took a holiday on the steamship ‘Almanzora’ visiting Buenos Aires (Argentina) St Vincent; Santos; Rio De Janeiro (Brazil); Montevideo (Uruguay); Madeira; Cherbourg (France); Lisbon (Portugal); Vigo (Spain). In 1926-1927 she visited Australia. In 1935 (aged 76) set off in the Blue Funnel liner ‘Anchises’ heading for Cape Town, South Africa. (31)

Charlotte Wolseley Haig died at Thatched Cottage, Langstone, Llanwern, near Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales, on 25th February 1937. Effects valued at £19,459 17s. 4d.

Primary Sources

(1) Angela V. John, Turning the Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda (2013)

Margaret's favourite aunt, also her godmother, was.... Aunt Lottie (Charlotte) Sybil's unmarried sister, who, along with many women of her day, sacrificed her desire for a profession to stay at home and look after her widowed father. Aunt Lottie enjoyed long hikes and was adored by the nieces and nephews who spent their summers at Pen Ithon. D. A. had the Thatched Cottage in Llanwern built for her. This four-roomed house was also designed by oswald Milne and enabled Lottie to be close to her relatives in her later years.

(2) Sylvia Pankhurst, Votes for Women (25th November 1910)

As, one after the other, small deputations of twelve women appeared in sight they were set upon by the police and hurled aside. Mrs Cobden Sanderson, who had been in the first deputation, was rudely seized and pressed against the wall by the police, who held her there by both arms for a considerable time, sneering and jeering at her meanwhile.

At first the crowds had pressed up close to the House in all directions, but after a fierce struggle the police drove them back and drew up their cordons so as to keep a clear space from the corner of Palace Yard to the Strangers' Entrance.

Just as this had been done, I saw Miss Ada Wright close to the entrance. Several police seized her, lifted her from the ground and flung her back into the crowd. A moment afterwards she appeared again, and I saw her running as fast as she could towards the House of Commons. A policeman struck her with all his force and she fell to the ground. For a moment there was a group of struggling men round the place where she lay, then she rose up, only to be flung down again immediately. Then a tall, grey-headed man with a silk hat was seen fighting to protect her; but three or four police seized hold of him and bundled him away. Then again, I saw Miss Ada Wright's tall, grey-clad figure, but over and over again she was flung to the ground, how often I cannot say. It was a painful and degrading sight. At last, she was lying against the wall of the House of Lords, close to the Strangers' Entrance, and a number of women, with pale and distressed faces were kneeling down round her. She was in a state of collapse.

The same kind of treatment was meted out to other women. I saw one tall woman in a white coat hit about the head and knocked down several times. Close to where my car was standing two young girls with linked arms were being dragged about by two policemen, and a man in plain clothes came up and kicked one of them, whilst a number of others stood by and jeered.

Never, in all the attempts which we have made to carry our deputations to the Prime Minister, have I seen so much bravery on the part of the women and so much violent brutality on the part of the policeman in uniform and some men in plain clothes. It was at the same time a gallant and a heart-breaking sight to see those little deputations battling against overwhelming odds, and then to see them torn asunder and scattered, bruised and battered, against the organized gangs of rowdies. Happily, there were many true-hearted men in the crowd who tried to help the women, and who raised their hats and cheered them as they fought.

I found out during the evening that the picked men of the A Division, who had always hitherto been called out on such occasions, were this time only on duty close to the House of Commons and at the police station, and that those with whom the women chiefly came into contact had been especially brought in from the outlying districts. During our conflicts with the A Division they had gradually come to know us, and to understand our aims and objects, and for that reason, whilst obeying their orders, they came to treat the women, as far as possible, with courtesy and consideration. But these men with whom we had to deal on Friday were ignorant and ill-mannered, and of an entirely different type. They had nothing of the correct official manner, and were to be seen laughing and jeering at the women whom they maltreated.