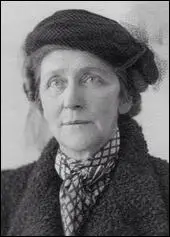

Helen Craggs

Helen Craggs, the daughter of Sir John Craggs, an accountant, was born in Westminster, London, on 24th November 1888. She was educated at Roedean and wanted to go to university to study medicine, but her father rejected the idea. Instead, she returned to Roedean where she taught physics and chemistry. (1)

In 1908 Helen Craggs, using the name Helen Miller, joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1908. She campaigned at the Peckham by-election for Thomas Gautrey, the Liberal Party candidate who supported women's suffrage. However, he was beaten by Henry Gooch, the Conservative Party candidate, with 60.9% of the vote. (2)

At an election meeting in January 1908 a WSPU member had asked Winston Churchill "as a member of the Liberal government whether he will or will not give a vote to the women of this country." Churchill replied: "The only time I have voted in the House of Commons on this question, I voted in favour of women's suffrage, but having regard of the perpetual disturbance at public meetings at this election, I utterly decline to pledge myself." (3)

Helen Craggs in Manchester

Winston Churchill won the election but after his appointment as President of the Board of Trade, as the Ministers of the Crown Act required newly appointed Cabinet ministers to re-contest their seats. Helen Craggs joined other members of the WSPU, including Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Flora Drummond, Constance Markievicz, Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth. in the harassment of Churchill, at the Manchester North-West by-election. (4)

Churchill lost the election by 1,241 votes. The winning Conservative Party candidate, William Joynson-Hicks, admitted: "I acknowledge the assistance I have received from those ladies who are sometimes laughed at, but who, I think, will now be feared by Mr. Churchill – the Suffragists." This press admitted that the opposition of the WSPU had largely contributed to Churchill's defeat. (5)

The Manchester Guardian reported: "Against Mr Churchill have been arrayed not merely the regular and legitimate forces of the political party to which he is opposed, but those of a dozen outside organisations as well. Nor is it with his natural enemies alone that he has had to contend. A pledged supporter of women's suffrage, he has been persistently assailed by several women's organisations. (6)

While in Manchester, Helen Craggs became romantically involved with Harry Pankhurst (the son of Emmeline Pankhurst). However, in April 1909, he became ill with serious inflammation of the bladder. He was cared for at a nursing home run by the suffragette Catherine Pine. According to June Purvis: "Harry told Sylvia, not their mother, that he longed to see Helen again. Soon the young woman was at Harry's bedside, telling him that she loved him too. But for the grief-stricken Emmeline, possessive of her only surviving son, the sight of the growing tenderness between the two young people was too much to bear. She chided Sylvia for acting on her own initiative. This young woman was taking from her the last precious moments with her boy." Harry died on 5 January 1910. (7)

WSPU Militant

On 21 November 1910, David Lloyd George was making a speech at the Paragon Theatre, Whitechapel. Helen Craggs, and two friends, had broken into the theatre the previous night and climbed onto the roof "only sustained by a few pieces of chocolate they lay through the whole bitter freezing night". When Lloyd George started his speech Helen charged the platform. She was soon captured by the stewards, but "armed with a super-human strength she tore herself free". Votes for Women reported that the stewards were "absolutely appalling in its brutality. Miss Craggs was practically thrown head foremost down the stone steps." (8)

In February 1910 Helen Craggs took over from Grace Roe as full-time organizer of the Women's Social and Political Union In Brixton on the salary of 25 shillings per month. During this period, she became close to Ethel Smyth, Evelyn Sharp and Beatrice Harraden. In March 1912 she was imprisoned in Holloway after taking part in the window-smashing campaign and went on hunger strike. (9)

On 25 th June 1912, King George V visited Wales in order to lay the foundation stone for the new National Museum of Wales in Cardiff. The Daily Telegraph reported: "While the Royal party was proceeding to the building, a woman jumped a wall and rushed towards the Home Secretary, who was in attendance, threatening vengeance for "the sufferance of the women in Holloway." The women's action really fell very flat, though doubtless she received the advertisement she desired. The only person excited by the incident was the woman herself. Everyone recognised that the object of her attack was not the King and Queen, but for Mr McKenna, and it is rather fortunate for the Suffragist that the spectators understood her purpose, for she would have run the risk of a severe handling from the crowd if she had forced her attentions on their Majesties. As it was, the woman, who is not a resident of the district, was loudly hooted. The police liberated her after an hour's detention." (10)

It was the Daily Sketch who identified the woman as Helen Craggs: "A remarkable incident occurred as the Royal party was approaching Cathays Park. A lady, who subsequently gave her name as Helen Craggs, sprang at the Home Secretary, who was in attendance on their Majesties. She shouted at Mr McKenna that it was a shame he was going about the country where suffragists were starving in prison and had to be removed by force." (11)

In July 1912, Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. (12)

Young Hot Bloods

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered by the conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. (13) It has speculated that this group included Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Mary Richardson, Miriam Pratt, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt, Olive Wharry and Florence Tunks. (14)

Helen Craggs volunteered her services and on 13th July 1912 Craggs and another woman were found by P.C. Godden at one o'clock in the morning outside the country home of the colonial secretary Lewis Harcourt. He went towards them and asked them what they were doing. Craggs, said they were looking round the house. The policeman said, "This is not a very nice time for looking round a house. How did you come here? Where do you come from?" Craggs said that they had been camping in the neighbourhood. The police-constable said he had not seen any encampment. She then said they had arrived by the river. Godden seized Miss Craggs and arrested her, and she was taken into custody. (15)

Helen Craggs appeared at Bullingdon Petty Sessions the next day. According to Votes for Women, "Miss Craggs, who carried a bunch of flowers in the colours, was evidently the centre of much sympathy from the public in the Court." (16) Helen pleaded guilty to the charge of "being in the garden…. For an unlawful purpose, to commit a felony, to unlawfully and maliciously set fire to a house and building belonging to Mr Harcourt". The judge argued that because of the seriousness of the crime - eight people were asleep in the house - bail was refused. (17)

The police suspected that the other woman was Ethel Smyth. She was arrested the next day but was released as "she was able without difficulty to satisfy the Bench completely as to her movements on the night in question." (18) Over fifty years later Norah Smyth confided the truth to her nephew, former diplomat Kenneth Isolani Smyth, that she was with Helen Craggs in the attempt to set fire to Harcourt's house. "He expressed surprise, knowing her love of old paintings and antiques, but Smyth explained that she knew the east wing of the house was uninhabited. It was the only violent action that she undertook as a suffragette." (19)

At her trial it was revealed that a typewritten statement was found in her handbag: "Sir, it is with a deep sense of my responsibility and a sincere conviction that my action is justifiable that I have taken a serious step in the cause of women's enfranchisement… I deplore that though during the past six years the demand for political liberty for women has become the greatest agitation of the time, politicians were content to see the supporters violently treated and unjustly imprisoned rather than give them the long-delayed and much-needed measure of justice which they demanded." (20)

It was claimed that the women were carrying a basket and a satchel. These contained "a bottle and two cans, which contained nearly three pounds of inflammable oil, four tapers, two boxes of matches, twelve fire-lighters, nine picklocks, an electric torch, a glass-cutter, and thirteen keys." (21)

Helen Craggs was sentenced to serve nine months with hard labour in Holloway. She went on hunger strike and was force-fed five times over two days. Her health was extremely bad and she was released after eleven days, suffering from internal and external bruising. In 1913 she went to Dublin to train as a midwife and a year later married Dr Alexander McCombie, who was working in the East End of London. (22)

Later Life

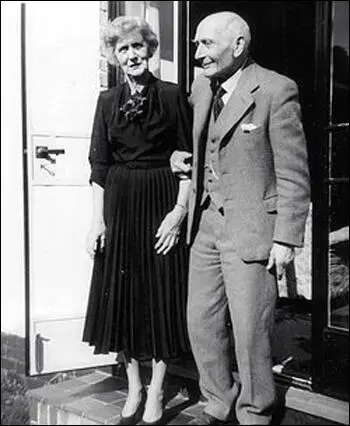

Helen qualified as a pharmacist in order to act as her husband's dispenser. (23) The couple had two children Sarah (b. 1923) and John (b. 1925). Dr McCombie died aged 69 in 1936 and she started a business making jigsaw puzzles. Helen moved to Canada with her daughter after the war but returned in the early 1950s to work for Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, the former Labour Party cabinet minister. (24)

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence died on 11 th March 1954. Helen married Frederick on 14th February 1957. (25) After his death on 10 th September 1961, Baroness Helen Pethick-Lawrence moved to Canada to be with her daughter. She died on 15 January in Victoria, British Columbia. (26)

Primary Sources

(1) June Purvis, Emmeline Pankhurst : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September 2004)

Emmeline's hopes of economic security for her son were suddenly dashed when, in April 1909, he became ill with serious inflammation of the bladder. The worried mother brought her son back to London, to the nursing home of two suffragette friends, Gertrude Townend and Catherine Pine. Here Harry was cared for and attended by Dr. Mills to whom Emmeline had to pay medical bills of £4. 4s. Soon she was back again in the provinces, campaigning for the vote, but also making sure that she spent some brief spells in London where she could see her boy. She was delighted when Harry improved enough to accompany her to the WSPU grand bazaar, held in Knightsbridge from 13- 26 May. ‘What a charming boy', people came up to her and said. ‘I did not know you had a son.' As he seemed fully recovered, Harry returned to Fels' farm...

When Emmeline returned to England she heard the dreadful news that Harry would never walk again, and that his future was bleak. Unknown to his mother, Harry had fallen in love with Helen Craggs, a young woman he had met when by-election campaigning in Manchester the previous year. And Harry told Sylvia, not their mother, that he longed to see Helen again. Soon the young woman was at Harry's bedside, telling him that she loved him too. But for the grief-stricken Emmeline, possessive of her only surviving son, the sight of the growing tenderness between the two young people was too much to bear. She chided Sylvia for acting on her own initiative. This young woman was taking from her the last precious moments with her boy.

When Emmeline returned to England she heard the dreadful news that Harry would never walk again, and that his future was bleak. Unknown to his mother, Harry had fallen in love with Helen Craggs, a young woman he had met when by-election campaigning in Manchester the previous year. And Harry told Sylvia, not their mother, that he longed to see Helen again. Soon the young woman was at Harry's bedside, telling him that she loved him too. But for the grief-stricken Emmeline, possessive of her only surviving son, the sight of the growing tenderness between the two young people was too much to bear. She chided Sylvia for acting on her own initiative. This young woman was taking from her the last precious moments with her boy. Emmeline was at Harry's bedside when he died on 5 January 1910.

(2) The Manchester Guardian (23rd April 1908)

Against Mr Churchill have been arrayed not merely the regular and legitimate forces of the political party to which he is opposed, but those of a dozen outside organisations as well. Nor is it with his natural enemies alone that he has had to contend. A pledged supporter of women's suffrage, he has been persistently assailed by several women's organisations.

(3) The Daily Sketch (26 June 1912)

A remarkable incident occurred as the Royal party was approaching Cathays Park. A lady, who subsequently gave her name as Helen Craggs, sprang at the Home Secretary, who was in attendance on their Majesties. She shouted at Mr McKenna that it was a shame he was going about the country where suffragists were starving in prison and had to be removed by force.

(4) The Daily Telegraph (26 June 1912)

While the Royal party was proceeding to the building, a woman jumped a wall and rushed towards the Home Secretary, who was in attendance, threatening vengeance for "the suffrance of the women in Holloway." The women's action really fell very flat, though doubtless she received the advertisement she desired. The only person excited by the incident was the woman herself. Everyone recognised that the object of her attack was not the King and Queen, but for Mr McKenna, and it is rather fortunate for the Suffragist that the spectators understood her purpose, for she would have run the risk of a severe handling from the crowd if she had forced her attentions on their Majesties. As it was, the woman, who is not a resident of the district, was loudly hooted. The police liberated her after an hour's detention.

(5) Votes for Women (2nd August 1912)

In the early hours of the morning of July 13, P. C. Godden, of the Oxfordshire Constabulary, was on duty in Nuneham Park when his attention was attracted by two ladies who were standing up close to the wall of Nuneham House, and he went towards them and asked them what they were doing. One of the ladies, Miss Craggs, said they were looking round the house. The policeman said, "This is not a very nice time for looking round a house. How did you come here? Where do you come from?"

Miss Craggs said that they had been camping in the neighbourhood. The police-constable said he had not seen any encampment. She then said they had arrived by the river. The police-constable having asked them to give an account of themselves, and receiving no satisfactory account from his view, decided to arrest, if he could, the two ladies. He seized Miss Craggs and arrested her, and she was taken into custody. The other lady escaped. The officer found on the scene of this meeting and struggle which he had with Miss Craggs the basket and satchel produced.

In the receptacles there were discovered, by later examination, a bottle and two cans, which contained nearly three pounds of inflammable oil, four tapers, two boxes of matches, twelve fire-lighters, nine picklocks, an electric torch, a glass-cutter, and thirteen keys.

(6) Votes for Women (26th July 1912)

Miss Helen Craggs, who was arrested in Nuneham Park on July 13, and remanded in custody, appeared at the Bullingdon Sessions at Oxford on Saturday last.

The court was crowded with Suffragists and sympathisers, and several people were ready to stand bail to any amount required. This was, however, not allowed, in spite of the fact that, as the magistrates were no doubt aware, no Suffragist prisoner has ever failed to appear; and with an extra-ordinary prejudging of the case, which almost amounts to contempt of his own Court, the chief magistrate expressed his opinion that an "atrocious crime had been attempted."

Miss Craggs, who carried a bunch of flowers in the colours, was evidently the centre of much sympathy from the public in the Court….

Miss Helen Craggs… was charged with being found at 1 a.m. on July 13 upon a garden in the occupation of Mr Lewis Harcourt, M.P., for an unlawful purpose, to wit, to commit a felony, to unlawfully and maliciously set fire to a house and building belonging to Mr. Harcourt.

Mr Walsh applied for bail and remarked that any amount would be forthcoming. He reminded the Bench that Miss Craggs had been in prison for a week. In this case there had been no previous conviction, and the prisoner was prepared to give the magistrates an undertaking that meantime she would not engage in any unlawful act or in any work whatsoever connected with the Suffrage movement….

Dr Ethel Smyth, the well-known composer and Suffragist, was arrested on Tuesday last at her house, The Coign, Woking, on a charge of being concerned in an attempt to burn down Mr Lewis Harcourt's house in Oxford. According to reports in the press, Dr Smyth is confident of being able to prove an alibi.

(7) Votes for Women (2nd August 1912)

Miss Ethel Smyth, of Woking, the well-known composer, who was arrested some days later on a charge of complicity in the same offence, was discharged at a special session held on July 26, but earlier than the other proceedings, to which the Press representatives were not admitted. It is understood that the magistrates apologized to Dr Smyth for her detention, and she was able without difficulty to satisfy the Bench completely as to her movements on the night in question. It is not surprising that none of the witnesses was able to identify her!

(8) Votes for Women (2nd August 1912)

Miss Helen Craggs – the ardent worker for the Cause who thought of nothing of a leap from roof to roof over a perilously deep drop in order to get the necessary message of "Votes for Women" into Mr Churchill's meeting some time ago – is an admirable example of the criminal folly of the Liberal Government – criminal folly because any man, save those who were absolutely blinded by party, would know how to put to better use such courageous and earnest youth.

Student Activities

References

(1) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 146

(2) The Times (25 March 1908)

(3) Winston Churchill, speech at St John's School in Manchester (9 January 1908)

(4) Votes for Women (30 April 1908)

(5) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931) page 280

(6) The Manchester Guardian (23 rd April 1908)

(7) June Purvis, Emmeline Pankhurst : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(8) Votes for Women (25 th November 1910)

(9) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 147

(10) The Daily Sketch (26 June 1912)

(11) The Daily Telegraph (26 June 1912)

(12) David J. Mitchell, Queen Christabel (1977) page 180

(13) Yorkshire Evening Post (8th May 1913)

(14) John Simkin, The WSPU Young Hot Bloods and the Arson Campaign (26th May, 2022)

(15) Votes for Women (2 nd August 1912)

(16) Votes for Women (26 th July 1912)

(17) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) pages 335-336

(18) Votes for Women (2nd August 1912)

(19) Carla Mitchell, Norah Smyth, Suffragette Photographer (1 November, 2018)

(20) The Times (2nd August 1912)

(21) Votes for Women (2 nd August 1912)

(22) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 337

(23) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000) page 147

(24) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 532

(25) Brian Harrison, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (6 January, 2011)

(26) Diane Atkinson, Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) page 532