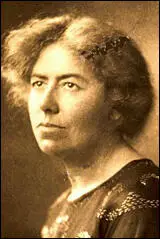

Olive Hockin

Olive Hockin was born in Bude, Cornwall, on 20th December, 1880. Her father, Edward Hockin (1838-1880), was a wealthy landowner and her mother Margaret Sarah Hoyer (1855-1919), was a clergyman's daughter. (1)

As a teenager she spent time in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She returned to London in 1897 to study at the Slade School of Fine Art where she took a mixture of full and part-time courses. (2)

Hockin was a contributor to Orpheus, the journal of the Theosophical Society. The editorial of the journal stated "we are a group of artists who revolt against the materialism of most contemporary art. We are adherents of that ancient philosophic idealism which is known to our times as theosophy." In the first few editions the journal included a reproduction of her paintings, The Blue Closet (3) and A Phantast (4). She also wrote a an article Impressions of the Italian Futurist Painters. (5)

Hockin joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1912. Its newspaper, Votes for Women, reported that she had become "a new worker in our movement" and was producing banners for the Bastille Day rally that was to take part in Hyde Park on 14th July 1912. (6) Later she said she joined "the movement, and had worked in it heart and soul, because it was a deeply rooted conviction that the world would be fairer and the conditions of life better for men, as well as for women and children, if women shared in the government." (7)

In July 1912, Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. (8) In January 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst made a speech where she stated that it was now clear that Herbert Asquith had no intention to introduce legislation that would give women the vote. She now declared war on the government and took full responsibility for all acts of militancy. "Over the next eighteen months, the WSPU was increasingly driven underground as it engaged in destruction of property, including setting fire to pillar boxes, raising false fire alarms, arson and bombing, attacking art treasures, large-scale window smashing campaigns, the cutting of telegraph and telephone wires, and damaging golf courses". (9)

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered by the conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. (10) It has speculated that this group included Olive Hockin, Helen Craggs, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Miriam Pratt, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt, Olive Wharry and Florence Tunks (11)

On 19th February, 1913, an attempt was made to blow up a house which was being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, near Walton Heath Golf Links. "One device had exploded, causing about £500 worth of damage, while another had failed to ignite." (12) Sir George Riddell who had commissioned the house, wrote in his diary that Lloyd George: "Said the facts had not been brought out and that no proper point had been made of the fact that the bombs had been concealed in cupboards, which must have resulted in the death of 12 men had not the bomb which first exploded blown out the candle attached to the second bomb, which had been discovered, hidden away as it was. He was very indignant." (13) Lloyd George wrote to Riddell and apologised for being "such a troublesome and expensive tenant" and that the WSPU should be made to pay for the damage. (14)

That evening in a speech at Cory Hall, Cardiff, Emmeline Pankhurst declared "we have blown up the Chancellor of Exchequer's house' and stated that "for all that has been done in the past I accept responsibility. I have advised, I have incited, I have conspired". Pankhurst concluded that extreme methods were needed because "No measure worth having has been won in any other way." (15)

Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested and charged with "incitement to commit arson". On 3rd April she was sentenced to three years' penal servitude and immediately went on hunger strike. No attempt was ever made to feed her forcibly and the Prisoners' (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Bill (Cat & Mouse Act), which allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be released to recover their health before being returned to prison, was rushed through to ensure that she did not die in prison. (16)

Police records show that the police suspected Olive Hockin and Norah Smyth of being the people who had carried out the attempt to blow up Lloyd George's house. As Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "It is clear from the New Scotland Yard reports of the investigation that Olive Hockin's address had been under surveillance. Her absence from home, the manner of her departure and the time of her return are all noted in the police report." (17)

On 12th March 1913 the police raided Olive Hockin's flat as she was suspected an arson attack on Roehampton Golf Club. In the flat they discovered a "suffragette arsenal" that included "a perfect arsenal of implements of destruction, including bottles of corrosive fluid, clippers for cutting telegraph wires, fire lighters, hammers, flints, tools of all descriptions in addition to a number of false motor-car identification plates, etc..." (18)

Olive Hockin was charged with "conspiring with others unknown to set fire to the croquet pavilion, the property of Roehampton Golf Club (26 February), to commit damage to an orchid house at Kew Gardens (8 February) and to cut telephone wires on various dates", and with "placing certain fluid in a Post Office letter-box in Ladbroke Grove (12 March)". (19) At her trial it was disclosed that a copy of the Daily Herald and of The Suffragette, which was found inside the dropped bag had her name and address penciled on them. Her caretaker later identified the handwriting as that of their local newsagents. (20)

At her trial Hockin admitted that she had been drawn into the militant suffrage movement after she became aware of the evils of prostitution. (21) In court it was stated that Hockin had been seen by "a police officer to ride a bicycle along the High Street, Notting Hill, and turn into Ladbroke Road, where the pillar-box stood. When the officer got up to the letter-box he saw some fluid trickling out of the bottom." (22)

In court it was admitted that Olive Hockin had been under surveillance for several weeks and on 26th February, the night of the attack in Roehampton, Hockin was seen to be acting suspiciously. Votes for Women reported: "In the evening a motor-car, driven by a lady, stopped at the house. Some parcels and long rods were taken out of the studio and strapped to the side of the car. The defendant (Olive Hockin) and another lady left in the car at about 10.30." About four o'clock the next morning the witness heard the front door bang and someone pass up the stairs to the studio. Later in the morning Miss Hockin said she was sorry that the door banged, but 'the young lady did not know how to manage the door'. The witness "stated that Miss Hockin did not sleep at the studio on the night of the Roehampton affair." (23)

Mrs Hall, her landlady, pointed out that the following morning Olive Hockin left out two pairs of boots to be cleaned, and only one pair of which belonged to the prisoner. The second pair had mud and grass on them, at the sight of which Mrs Hall remembered reading an article about a fire at the Roehampton Pavilion. Later that day Mrs Hall heard Hockin being visited by two young women carrying gentleman's "dressing-cases". (24)

Olive Hockin claimed she was not guilty of these charges. She also objected to the male dominated justice system: "A court composed entirely of men have no moral right to convict and sentence a woman, and until women have the power of voting I shall continue to defy the law, whether I am in prison or out of it." (25)

Judge Charles Montague Lush formally withdrew the charges relating to the attack on the orchid house, telephone-wire cutting and the pillar-box attack,. His summing-up showed sympathy for Olive Hockin and commented there was no evidence that she was present at Roehampton. Lush also controversially commented that she was a "woman who in her zeal had joined in a cause which she thought was a thoroughly good cause, and she might be right in thinking so." (26) Olive was sentenced to four months imprisonment and ordered to pay half the costs of the prosecution. (27)

Soon after her arrival surveillance photographs of Olive Hockin were taken from a van parked in the prison exercise yard. Olive appears with Margaret Schenke, Jane Short and Margaret Mcfarlane. The images were compiled into photographic lists of key suspects, used to try and identify and arrest Suffragettes before they could commit militant acts. (28)

Olive Hockin threatened to go on hunger strike and it was transferred to the First Division, and agreed to serve her sentence on condition of being permitted to carry on as an artist in prison. (29) Margaret Schenke claimed that she carved the chair in her cell. (30)

exercising in the yard of Holloway prison (March 1913)

Sylvia Pankhurst grew increasingly unhappy about the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) decision to abandon its earlier commitment to socialism. She also rejected the WSPU attempts to gain middle class support by arguing in favour of a limited franchise. Pankhurst made the final break with the WSPU when the movement adopted a policy of widespread arson. Sylvia now concentrated her efforts on helping the Labour Party build up its support in London. (31)

In 1913, Sylvia Pankhurst, with the help of Keir Hardie, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Maud Joachim, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. Pankhurst also began production of a weekly paper for working-class women called The Women's Dreadnought. (32)

As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy. Between February 1913 and August 1914 Sylvia was arrested eight times. After the passing of the Prisoners' Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act of 1913 (known as the Cat and Mouse Act) she was frequently released for short periods to recuperate from hunger striking and was carried on a stretcher by supporters in the East End so that she could attend meetings and processions. When the police came to re-arrest her this usually led to fights with members of the community which encouraged Sylvia to organize a people's army to defend suffragettes and dock workers. She also drew on East End traditions by calling for rent strikes to support the demand for the vote." (33)

On her release from prison Olive Hockin left the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and joined the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). Sylvia Pankhurst, known as "Our Sylvia", operating from her shop in Bow Road, recruited women who were working in local factories and sweatshops. Branches were formed in Bow & Bromley, Stepney, Limehouse, Bethnal Green, Hackney and West Ham. Hockin organised the Poplar branch that she ran from her home at 28 Campden Hill Gardens, Kensington. (34)

Olive Hockin continued to work as an artist and produced one of her most important paintings, Pan! Pan! O Pan! Bring Back thy Reign Again Upon the Earth (1914) during this period. She continued exhibiting at the Society of Women Artists, at the Walker Art Gallery and the Royal Academy. (35)

With growing numbers of men joining the British armed forces during the First World War, the country was desperately short of labour. The Government decided that more women would have to become more involved in producing food and goods to support their war effort. This included the establishment of the Women's Land Army. According to her own account, she had "just walked up to offer my services' to a Dartmoor farmer, after having seen his advertisement for a casual labourer." She saw his wife first who commented: "Well really! You must come in and tell me about it. I am afraid my husband only laughs at the idea. He says that a woman about the place would be more trouble than she is worth, and we quite made up our minds that no woman could possibly do the work!"' In 1918 she published her own account of her experiences, Two Girls on the Land: Wartime on a Dartmoor Farm. (36)

The book was favourably reviewed in the The Common Cause, the newspaper of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. "There is no attempt to cloak the real grind of hard days that lie behind the phrase "work on the land". Here you have it all clearly stated - the long, long hours, the consistent pressure of work, the mud in the winter, the heat in the summer - and through it all the things that competence and make one glad to one's best to "carry on". It is not possible here to set out the many paragraphs worth quoting, but to anyone who reads the book I can testify to the truth of every line." (37)

In the summer of 1922 she married John Leared, the proprietor of a Cheltenham polo-pony training school. She became the mother of two sons, Oliver Leared (born 1926) and Nicholas Leared (born 1929). The family lived at Colmans, Elmstone Hardwicke. (38)

Olive Hockin died at Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, on 5th February, 1936.

Primary Sources

(1) David Simkin, Family History Research (4th May, 2020)

On Ancestry there are a number of Family Trees that feature Olive Hockin and they all give her birth details as follows: Olive Hockin , born 20th December 1880 at Bude, Cornwall . The same family trees record her death as follows: Olive Hockin , died 5th February 1936 at Cheltenham, Gloucestershire.

Olive Hockin was the daughter of a wealthy landowner and JP named Edward Hockin (1838-1880) and Margaret Sarah Hoyer (1855-1919), a clergyman's daughter. Her father Edward Hockin is described on the 1871 census as " Landowner, Farmer & Merchant ".

Edward Hockin (a widower of 37 with three children from his first marriage) married 21-year-old Margaret Sarah Hoyer on 31st October 1876. Edward Hockin's second marriage produced three more children - Arthur (b. 1877), Frank (b. 1878 - d. 1880) and Olive (born 20th December 1880). Edward Hockin died in London on 29th May 1880 - i.e. 7 months before the birth of Olive. When he died, Edward Hockin left a " Personal Estate worth under £9,000 ". When the 1881 Census was taken Olive was recorded as a child "under 4 months". Her mother is recorded as a 25 year old widow at a house in Stratton, Cornwall. She has "no occupation", but is employing 3 live-in domestic servants. At the time of the 1891 census, 10-year-old Olive was living with her widowed mother in the Hampshire village of Sherborne St John, near Basingstoke. Mrs Margaret Hockin, a 35-year-old widow " Living on own means " was employing four domestic servants, including a groom, a cook and two housemaids.

In February 1895, 14-year-old Olive Hockin returned to England with her mother after a trip to Buenos Aires, Argentina . On 26th April 1897, 16-year-old Olive Hockin returned alone to England (Southampton) after another trip to Buenos Aires.

On 1st Sept 1896, Olive's 40-year-old widowed mother, Mrs Margaret Sarah Hockin (nee Hoyer ) married John Townsend Kirkwood (born 1814, New Brunswick, Canada), an 81 year old " Landowner & J.P. " John Townsend Kirkwood died in Tenerife, Canary Islands on 10th January 1902 leaving effects worth £5,043.

On the 1911 Census form, Olive Hockin is described as a 30 year old (unmarried) "Artist". She is living with her 55-year-old widowed mother Mrs Margaret Sarah Kirkwood at Audrey, Burghfield Common, near Reading, Berkshire.

During the 3rd Quarter of 1922 (July-Aug-Sept) at Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, Wales, Olive Hockin married John Harvey Leared (born 1874, Wexford, Ireland - died 1952, Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland). They had two sons Richard Oliver Leared (1926-2000) and Nicholas Leared (born 1929, Wandsworth).

Mrs Olive Leared (nee Hockin) died on 5th February 1936 at Cheltenham General Hospital, Gloucestershire.

She had personal effects valued at £8,097. Her home address is given as Colmans, Elmstone Hardwicke, Cheltenham. In the probate entry, her husband, John Harvey Leared is described as " the proprietor of a polo pony training school ". John Harvey Leared was previously in business as an " Export Agent of Lime juice etc.". [1911 Census].

(2) Votes for Women (21st March, 1913)

Miss Olive Hockin, an artist, was brought before Mr. Fordham at the West London Police Court the next morning on a warrant, charging her with conspiring, combining, confederating, and agreeing, on February 26, with other persons unknown, unlawfully and maliciously to set fire to a pavilion at Roehampton.

The arrest it was stated, was regarded by the the authorities as of importance, by reason of the fact that, at the studio of which the defendant was said to be the occupier, there was found a perfect arsenal of implements of destruction, including bottles of corrosive fluid, clippers for cutting telegraph wires, fire lighters, hammers, flints, tools of all descriptions in addition to a number of false motor-car identification plates, etc...

At the next hearing the case would be opened fully, and there would be adducted clear evidence connecting the defendant with the ownership of a bag which was found on the night of February 26 on the golf-links at Roehampton. The contents of the bag were of an inflammable character. On that night, continued Mr. Bodkin, two women were seen at ten o'clock by the groundsman on the golf-links.

On observing him they ran away and in their flight one of them dropped the bag. The groundsman picked it up. It would be shown that the contents of the bag belonged to the defendant, and came from her house at Campden Hill Gardens, Kensington.

(3) Votes for Women (28th March, 1913)

At West London Police Court on Thursday, March 20, before Mr Fordham, Miss Olive Hockin, an artist, surrendered to her bail to answer the charge of conspiring with other persons unknown to set fire to a pavilion on the golf links at Roehampton on February 26.

Mr Bodkin, prosecuting, stated that the defendant would be charged under the Post Office Protection Act, 1908, with damaging a number of letters in the letter-box at Ladbroke Road, Notting Hill.

Dealing with the second charge against the accused, Mr Bodkin stated that on March 12 she was seen by a police officer to ride a bicycle along the High Street, Notting Hill, and turn into Ladbroke Road, where the pillar-box stood. When the officer got up to the letter-box he saw some fluid trickling out of the bottom.

(4) Votes for Women (4th April, 1913)

In the evening a motor-car, driven by a lady, stopped at the house. Some parcels and long rods were taken out of the studio and strapped to the side of the car.

The defendant (Olive Hockin) and another lady left in the car at about 10.30. About four o'clock the next morning the witness heard the front door bang and someone pass up the stairs to the studio. Later in the morning Miss Hockin said she was sorry that the door banged, but "the young lady did not know how to manage the door".

The witness found a lot of mud and pieces of grass on the defendant's boots. The same witness stated that Miss Hockin did not sleep at the studio on the night of the Roehampton affair.

(5) Votes for Women (11th April, 1913)

Miss Hockin said she would like to explain why she was in this position. She was not guilty of the charge against her, although she did not for one moment attempt to deny that she was a militant suffragist. She joined the movement, and had worked in it heart and soul, because it was a deeply rooted conviction that the world would be fairer and the conditions of life better for men, as well as for women and children, if women shared in the government.

She added: "A court composed entirely of men have no moral right to convict and sentence a woman, and until women have the power of voting I shall continue to defy the law, whether I am in prison or out of it.

(6) Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000)

Olive Hockin was charged with conspiring to set fire to a pavilion at Roehampton Golf Club, damaging the orchid house at Kew and pouring corrosive liquid into a letter box. She was also suspected by the police, although not charged, with the attack on Lloyd George's house at Walton Heath on 19 February, for which Mrs Pankhurst was awaiting trial for inciting commit arson. It is clear from the New Scotland Yard reports of the investigation that Olive Hockin's address had been under surveillance. Her absence from home, the manner of her departure and the time of her return are all noted in the police report.

(7) Olive Hockin – Suffragette, Artist and Land Girl (7th September 2018)

Olive's account of her year spent working the land on the Devon farm, entitled Two Girls on the Land: War Time on a Dartmoor Farm provides a valuable insight into the lifestyle and attitudes of what was, at the time, a fairly isolated way of life. Many farms had only gaslight and the days were long and tough, maintaining animals and growing crops in the unforgiving and rocky Dartmoor soil. Given this isolation, few farmers shared in the enthusiasm for war and Devon was known for its poor uptake on recruitment for the armed forces. Even less enthusiasm greeted upper and middle-class women offering themselves up as labourers. Olive notes the scepticism she was greeted with in Two Girls; ‘My lady gasped – but to do her justice, rose to the occasion with a bound. "Well really! You must come in and tell me about it. I am afraid my husband only laughs at the idea. He says that a woman about the place would be more trouble than she is worth, and we quite made up our minds that no woman could possibly do the work!"'

Nevertheless, in a short time Olive was taken on at 5 shillings a week with board and lodging ‘to do whatever I was told and go where I was bid.' She worked tirelessly for a full year, taking on all the duties of the absent male labourers. She ploughed, harnessed, drove, fed and watered, dosed, milked, cleaned, swept, dug, sowed and harvested.

Olive was likely born in December of 1880 to a West country family. After some time spent in Argentina as a teenager, she returned to London to study at the Slade School of Fine Art and went on to have her work shown at the Royal Academy. Gradually, her circles of artist friends lead her to establish links with women's suffrage and the WSPU. Although marked out as a militant by authorities as early as 1912, Olive came to some prominence in the movement when she was found guilty of an arson attack on Roehampton Pavilion and sentenced to four months imprisonment. The main image was taken without Olive's knowledge whilst in Holloway Prison awaiting trial, since Suffragettes regularly refused to co-operate when having their photographs taken for police records. Thus, she became one of the first subjects of secret police surveillance photography.

As the war years drew to a close, many female workers and farm hands were dismissed from their jobs in favour of returning servicemen. Little is known of Olive's time after the war as none of her writings remain. She married in 1922 at the age of 41 and bore two sons.

(8) Magda Michalska, An Artist Turned Suffragette. A Story of Olive Hockin (11th December, 2018)

She joined the Suffragette movement around 1912, and a year later she was arrested for 4 months accused of plotting to assassinate the Prime Minister. Indeed, she participated in arson attacks on the Roehampton Golf Club and on a house at Walton Heath, which belonged to David Lloyd George, and at the scene of the attack the police found papers bearing her name, while wire cutters, stones, false car number plates, and paraffin were later found at her home. To prison, she took with her prints of Love and Death by G. F. Watts and The Golden Stairs by Edward Burne-Jones and agreed not to go on hunger strike if she was allowed to paint. Her fellow prisoner, Margaret Scott, recalled that Olive carved the chair in her cell.

She continued exhibiting at the Society of Women Artists, at the Walker Gallery and until 1915 at the Royal Academy. During the First World War, she joined the Women's Land Army (WLA), a British civilian organisation which replaced with women those men who normally worked in agriculture but now were called up to the military. Olive was sent to a farm in Dartmoor, Devon. She wrote a book describing her experience as Land-girl (as such women were called) called Two Girls on the Land: Wartime on a Dartmoor Farm, published in London, 1918. Moreover, the rugged and mystical landscape of Dartmoor was a source of great inspiration to Olive's art.

Her life after the war is quite a mystery because Olive did not leave any writings from this period. The only thing known is that in 1922 she married John Leared, who was a trainer of polo ponies and they had two sons. She died in 1936.

(9) The Common Cause (2nd August 1918)

Hot from the stress of work comes a book of experiences, written in attractive English and essentially true to life, and is so doubly worth reading. Such a book is Two Girls on the Land, by Olive Hockin. As a land-worker of two years standing it is a pleasure to read it, and to anyone who is interested to know what land-worker it should be a stimulus to recruiting, though to those who are merely attracted by the uniform and the happy thought that "it must be so nice to be out in the fields all day" I fear it would be the reverse.

There is no attempt to cloak the real grind of hard days that lie behind the phrase "work on the land". Here you have it all clearly stated - the long, long hours, the consistent pressure of work, the mud in the winter, the heat in the summer - and through it all the things that competence and make one glad to one's best to "carry on". It is not possible here to set out the many paragraphs worth quoting, but to anyone who reads the book I can testify to the truth of every line.