Miriam Pratt

Annie Miriam Pratt was born in Windlesham, Surrey, on 26th January 1890. Her father Charles Pratt, was a "general labourer". In about 1898 she moved to Norwich to live with her maternal aunt, Harriet and her husband, William Ward, a sergeant in the Norwich City Police. As her parents were still alive it would seem that Harriet and William had informally adopted Miriam as they had no children of their own. (1)

Miriam went through the pupil-teacher training scheme while continuing to live with her aunt and uncle. By 1911 she was living at 7 Turner Road in Lakenham and working as an assistant teacher. Miriam also joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and would sell its newspaper, The Suffragette, on the streets of Norwich. (2)

In 1912 Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the WSPU gave permission for her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. Christabel knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. (3)

WSPU Arson Campaign

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." (4)

Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. (5)

Miriam Pratt and the Young Hot Bloods

Miriam Pratt, a member of the WSPU, did not share these concerns. As Fern Riddell has pointed out: "From 1912 to 1914, Christabel Pankhurst orchestrated a nationwide bombing and arson campaign the likes of which Britain had never seen before and hasn't experienced since. Hundreds of attacks by either bombs or fire, carried out by women using codenames and aliases, destroyed timber yards, cotton mills, railway stations, MPs' homes, mansions, racecourses, sporting pavilions, churches, glasshouses, even Edinburgh's Royal Observatory. Chemical attacks on postmen, postboxes, golfing greens and even the prime minister - whenever a suffragette could get close enough - left victims with terrible burns and sorely irritated eyes and throats, and destroyed precious correspondence." (6)

According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "When the policy was fully underway, certain officials of the Union were given, as their main work, the task of advising incendiaries, and arranging for the supply of such inflammable material, house-breaking tools and other matters as they might require. Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest." (7)

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered as a result of a conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. (8) During the trial, Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone." (9)

Balfour Biological Laboratory

It has been argued that this group included Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt, Olive Wharry and Florence Tunks. (10) Pratt joined the Young Hot Bloods and on 17th May 1913, she set fire to an empty building attached to the Balfour Biological Laboratory for Women, in Storey's Way, Cambridge, with paraffin-soaked cloth. (11) The building was erected in 1884 on for the use of women studying science at Newnham and Girton. The laboratory enabled women to learn about anatomy, dissection, microbiology, zoology, chemical compounds and physics. (12)

Fern Riddell has pointed out why Miriam selected this target: "But what good was a university laboratory, and a university education, if women were refused the right to be awarded their degrees? Although universities permitted women to attend courses and take exams, they were not allowed to graduate, and there was little opportunity for them to use the knowledge they acquired in the world outside the protected college atmosphere. Perhaps it was the unbearable unfairness of this inequality that removed any qualms Miriam and her companions might have felt that night, as they broke and set a fire that consumed a considerable amount of the adjoining building before the alarm was raised." (13)

When the police examined the scene of the fire they found suffrage literature. This was done to show the authorities that the crime had been committed by the WSPU in protest against the government's decision not to give the vote to women. Frank Meeres has pointed out that two buildings in Cambridge had been targeted, "first a new house being built for a Mrs Spencer of Castle Street, then a new genetics laboratory. Suffrage leaflets were found in both. A lady's gold watch was discovered outside the window of the laboratory which had been used to get in.... Blood had been found where the arsonist had cut herself while scraping out the putty around the window; Miriam had a corresponding wound." (14)

Miriam's uncle, William Ward, was involved in the investigation. He suspected the watch belonged to Miriam. When confronted by Ward about the matter she admitted that she had carried out the attack. As a result she was arrested and taken to the local police court. The Cambridge Independent Press reported that Miriam Pratt was a "tall, pretty girl", who was "dressed in a light blue corduroy coat, a blue cloth skirt, and black velvet toque trimmed with light blue ribbon." (15)

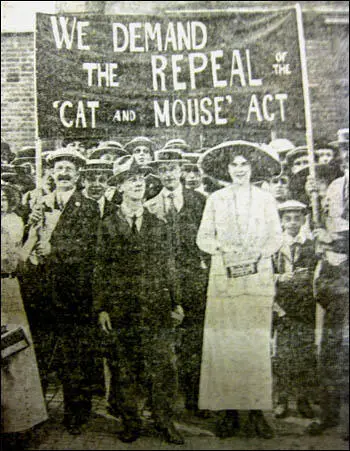

Miriam Pratt was remanded for eight days before being granted bail. The sureties of £200 was raised by a friend, Dorothy Jewson, a member of the WSPU and the Independent Labour Party. Miriam was suspended from her job at St Paul's National School in Norwich. On 18th July, Miriam attended a protest demonstration held on Norwich Market Place against the Cat and Mouse Act. (16)

Miriam Pratt appeared at Cambridge Assizes in October. She chose to represent herself. The main evidence against her came from her uncle. Miriam asked the judge: "Is it legal for the witness to give evidence of a statement he alleges to have obtained from me not having first cautioned me, he being a police officer?" The judge replied: "That does not disqualify him. He was not acting as a police officer." Miriam asked her uncle: "Don't you think it was your duty as a police officer to caution me?" He admitted "it was my duty, but I was speaking to you as a father would do, and I omitted to caution you." (17)

In her final statement to the court, Miriam admitted her guilt: "I ask you to look again at what has been done and see in it not wilful and malicious damage, but a protest against a callous Government, indifferent to reasoned argument and the best interests of the country. A protest carried to extreme because no other means would avail... show by your verdict today that to fight in the cause of human freedom and human betterment is to do no wrong." (18)

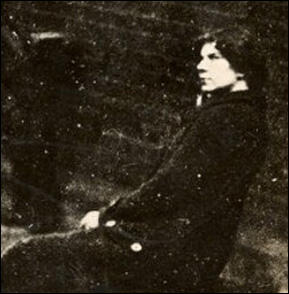

Miriam was sentenced to eighteen months' hard labour and sent to Holloway Prison. Soon after her arrival surveillance photographs of Miriam were taken from a van parked in the prison exercise yard. The images were compiled into photographic lists of key suspects, used to try and identify and arrest Suffragettes before they could commit militant acts. (19)

Miriam Pratt immediately went on hunger strike. The damage force-feeding had inflicted on Miriam was swift and brutal. The Suffragette reported: "Lord, help and save Miriam Pratt and all those being tortured in prison for conscience sake." (20) Doctors were worried about the impact this was having on her heart and released her and ordered three months' bed rest. (21)

Miriam's statement in court was printed as a leaflet and distributed by members of the Women's Social and Political Union and the Independent Labour Party. This campaign, organized by Dorothy Jewson, included giving out leaflets inside Norwich Cathedral. (22) Miriam was never recalled to prison because of the controversy created by the Cat and Mouse Act and the falling numbers of women willing to go to prison. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU was a spent force with very few active members. (23)

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War the WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (24)

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!". (25)

In October 1915, The WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom'. The newspaper attacked politicians and military leaders for not doing enough to win the war. In one article, Christabel Pankhurst accused Sir William Robertson, Chief of Imperial General Staff, of being "the tool and accomplice of the traitors, Grey, Asquith and Cecil". Christabel demanded the "internment of all people of enemy race, men and women, young and old, found on these shores, and for a more complete and ruthless enforcement of the blockade of enemy and neutral." (26)

Miriam Pratt, like her friend Dorothy Jewson, left the WSPU over its support for the war. She moved back to Norwich and on 19th May 1915 married Bernard Francis, a political activist who had been a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage. At the beginning of the First World War Francis had joined the Royal Engineers and eventually reached the rank of Lieutenant. (27)

William Ward must have forgiven Miriam because when he died in 1936 she inherited a half share of his property. Miriam moved to London where he worked as an Assistant Company Secretary. but kept in contact with her relatives in Norwich until her death at Horton Hospital in Epsom, Surrey on 24 June 1975. (28)

Primary Sources

(1) Fern Riddell, Death in Ten Minutes: The Forgotten Life of Radical Suffragette: Kitty Marion (2019)

On the week of the Cambridge fire she had told him she would be going to the city - although only, she said, to sell newspapers - and he had not stopped her. But Miriam had also been in cambridge a week earlier, at the same time as the bomb was found in the football pavilion - was it this that started to make him suspicious? Certainly it played on his mind enough for him to ask his wife to check if Miriam's gold watch was in her bedroom. It was not.

Confronted, Miriam begged him not to tell anyone the watch was hers. The betrayal must have been shocking for a man who had spent his life working to enforce the law; to discover that his niece, educated and hard-working, had committed such a dangerous crime. Miriam claimed she had nothing to do with the fire itself, but William had read about the broken windowpane, the blood found at the scene. He examined her hands. The cuts were clear.

(2) Gill Blanchard, Struggle and Suffrage in Norwich (2020)

Miriam's trial began on 14 October. despite a spirited defence which she conducted herself, she was convicted by Mr Justice Bray at Cambridgeshire Assize Court and sentenced to eighteen months, and subsequently sacked from her job. Miriam promptly went on hunger strike, and was transferred to Holloway Prison. After five days on hunger strike, Miriam was released from Holloway Prison under the Act on a seven-day licence. She was sent to the care of friends in Kensington, with the doctor recommending three months' rest.

(3) Miriam Pratt, statement in court (18th October, 1913)

I ask you to look again at what has been done and see in it not wilful and malicious damage, but a protest against a callous Government, indifferent to reasoned argument and the best interests of the country. A protest carried to extreme because no other means would avail... show by your verdict today that to fight in the cause of human freedom and human betterment is to do no wrong.

(4) Kitty Dinshaw, The Birth of Surveillance Photography (20th March, 2018)

Modern day surveillance photography started in Britain in 1913 with an unassuming prison van parked in the exercise yard of Holloway Prison. We only know the occupant of the van as Mr. Barrett, a professional photographer who had been employed by Scotland Yard to snap paparazzi-style shots of the women in the yard. His long-lens photography equipment - the purchase of which was authorised by the then Home Secretary - was rudimentary, but effective.

And who were these women Barrett was photographing? Members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), also, and perhaps better, known as the suffragettes. Suffrage campaigns were ongoing in both Europe and the United States in the early part of the 20th century, with Finland being the first country to grant women the right to vote and stand for office in 1906.

(5) Frank Meeres, Suffragettes: How Britain's Women Fought & Died for the Right to Vote (2013)

Militant suffragettes were active throughout the country, far too many to set down. A typical individual "outrage" was one in Cambridge on 18 May two buildings were down in the town, first a new house being built for a Mrs Spencer of Castle Street, then a new genetics laboratory. Suffrage leaflets were found in both. A lady's gold watch was discovered outside the window of the laboratory which had been used to get in. On 22 May a twenty-two-year-old Norwich schoolteacher, Miriam Pratt, was arrested; she had been shopped by her uncle, a policeman, who had recognised the watch. Blood had been found where the arsonist had cut herself while scraping out the putty around the window; Miriam had a corresponding wound.