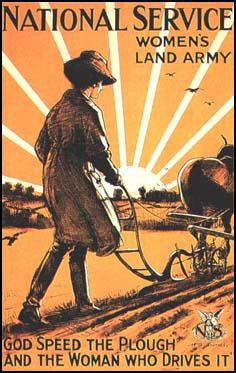

Women's Land Army

With growing numbers of men joining the British armed forces during the First World War, the country was desperately short of labour. The Government decided that more women would have to become more involved in producing food and goods to support their war effort. This included the establishment of the Women's Land Army. Some farmers resisted this measure and in 1916 the Board of Trade began sending agricultural organizing officers around the country in an effort to persuade farmers to accept women workers. This strategy worked and by 1917 there were over 260,000 women working as farm labourers.

The East Grinstead Observer reported that the campaign was very successful in Sussex: "Miss Bradley, agricultural organising officer for the Board of Trade, said that Sussex had been one of the best countries for recruiting for the army and navy, and she hoped that with the co-operation of the farmers it would occupy a similar position with regard to women working on the land and filling the places of the men who had gone to fight for their country. She knew that in Sussex there was a strong feeling against 'foreigners', and therefore it was all the more necessary that women of Sussex should help in this movement, so that it would not be necessary to import female labour from other counties. She believed that the home grown food supply would be a quarter below the average that year. Women generally had responded splendidly to this call for service. The same could not hardly be said of the farmers, but she realised that there were difficulties and prejudices were being gradually overcome and that when farmers realised that women could do useful work they would accept their service more and more readily."

Olive Hockin, a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) who had been convicted of arson, wrote about her experiences in the woman's land army, Two Girls on the Land: Wartime on a Dartmoor Farm (1918) . According to her own account, she had "just walked up to offer my services' to a Dartmoor farmer, after having seen his advertisement for a casual labourer." She saw his wife first who commented: "Well really! You must come in and tell me about it. I am afraid my husband only laughs at the idea. He says that a woman about the place would be more trouble than she is worth, and we quite made up our minds that no woman could possibly do the work!"'

Primary Sources

(1) The East Grinstead Observer (17th June, 1916)

At St. Michael's Parish Hall, Miss Bradley, agricultural organising officer for the Board of Trade, said that Sussex had been one of the best countries for recruiting for the army and navy, and she hoped that with the co-operation of the farmers it would occupy a similar position with regard to women working on the land and filling the places of the men who had gone to fight for their country. She knew that in Sussex there was a strong feeling against "foreigners", and therefore it was all the more necessary that women of Sussex should help in this movement, so that it would not be necessary to import female labour from other counties. She believed that the home grown food supply would be a quarter below the average that year. Women generally had responded splendidly to this call for service. The same could not hardly be said of the farmers, but she realised that there were difficulties and prejudices were being gradually overcome and that when farmers realised that women could do useful work they would accept their service more and more readily. Women were proving in many directions that they could perform useful work - in offices, in munition works, and she had even seen them assisting in tarring and repairing roads. On farms, too, they could be of great assistance they could do valuable work with weeding. Three pence an hour was the minimum wage for untrained helpers.

(2) David Lloyd George, War Memoirs (1938)

But the recruit to our agricultural labour force who attracted the liveliest interest was undoubtedly the land girl. Her aid, too, was at first pressed on the farmers in the teeth of a good deal of sluggish and bantering prejudice and opposition. When in 1915 the Board of Agriculture tried to induce the farming community to employ female labour - the "lilac sunbonnet brigade," as they were jocularly hailed in some quarters - it met at first with very little success. There was of course work that had long been done by women on family farms - milking, butter making, poultry keeping, haymaking and the like.

(3) Olive Hockin, wrote about her experiences in the woman's land army, Two Girls on the Land: Wartime on a Dartmoor Farm (1918) . The book was reviewed in The Common Cause (2nd August 1918)

Hot from the stress of work comes a book of experiences, written in attractive English and essentially true to life, and is so doubly worth reading. Such a book is Two Girls on the Land, by Olive Hockin. As a land-worker of two years standing it is a pleasure to read it, and to anyone who is interested to know what land-worker it should be a stimulus to recruiting, though to those who are merely attracted by the uniform and the happy thought that "it must be so nice to be out in the fields all day" I fear it would be the reverse.

There is no attempt to cloak the real grind of hard days that lie behind the phrase "work on the land". Here you have it all clearly stated - the long, long hours, the consistent pressure of work, the mud in the winter, the heat in the summer - and through it all the things that competence and make one glad to one's best to "carry on". It is not possible here to set out the many paragraphs worth quoting, but to anyone who reads the book I can testify to the truth of every line.