Women and Chartism

In June 1836 William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave, Henry Vincent, John Roebuck and James Watson formed the London Working Men's Association (LMWA). Although it only ever had a few hundred members, the LMWA became a very influential organisation. At one meeting in 1838 the leaders of the LMWA drew up a Charter of political demands. (1)

(i) A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime.

(ii) The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. (iii) No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice. (iv) Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation. (v) Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones. (vi) Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period." (2)

Although many leading Chartists believed in votes for women, it was never part of the Chartist programme. When the People's Charter was first drafted by the leaders of the London Working Men's Association, a clause was included that advocated the extension of the franchise to women. This was eventually removed because some members believed that such a radical proposal "might retard the suffrage of men". As one author pointed out, "what the LWMA feared was the widespread prejudice against women entering what was seen as a man's world". (3)

Chartist Female Associations

In most of the large towns in Britain, Chartist groups had women sections. The East London Female Patriotic Association published its objectives in October, 1839, and made it clear that they wanted to "unite with our sisters in the country, and to use our best endeavours to assist our brethren in obtaining universal suffrage". The organisation made the point that they would use their power as managers of the household to obtain the vote for their men by "to deal as much as possible with those shopkeepers who are favourable to the People's Charter". (4)

These women's groups were often very large, the Birmingham Charter Association for example, had over 3,000 female members. (5) The Northern Star reported on 27th April, 1839, that the Hyde Chartist Society contained 300 men and 200 women. The newspaper quoted one of the male members as saying that the women were more militant than the men, or as he put it: "the women were the better men". (6)

Elizabeth Hanson formed the Elland Female Radical Association in March, 1838. She argued "it is our duty, both as wives and mothers, to form a Female Association, in order to give and receive instruction in political knowledge, and to co-operate with our husbands and sons in their great work of regeneration." (7) She became one of the movement's most effective speakers and one newspaper reported she "melted the hearts and drew forth floods of tears". (8)

In 1839 Elizabeth gave birth to a son, who she named after Feargus O'Connor. She continued to be involved in the campaign for universal suffrage.Her husband, Abram Hanson, acknowledged the importance of "the women who are the best politicians, the best revolutionists, and the best political economists... should the men fail in their allegiance the women of Elland, who had sworn not to breed slaves, had registered a vow to do the work of men and women." (9)

Susanna Inge

Susanna Inge was another imprtant figure in the Chartist movement. As she explained in an article for The Northern Star in July, 1842. "As civilisation advances man becomes more inclined to place woman on an equality with himself, and though excluded from everything connected with public life, her condition is considerably improved". She went on to urge women to “assist those men who will, nay, who do, place women in on equality with themselves in gaining their rights, and yours will be gained also". (10)

In October 1842, Susanna Inge and Mary Ann Walker attempted to establish a Female Chartist Association. Inge argued that in time women should be given the vote. However, she felt before this could happen women "ought to be better educated, and that, if she were, so far as mental capacity, she would in every respect be the equal of man”. (11)

This plan to form a Female Chartist Association was criticised by some male Chartists. One declared that he "did not consider that nature intended women to partake of political rights". He argued that women were "more happy in the peacefulness and usefulness of the domestic hearth, than in coming forth in public and aspiring after political rights". (12)

It was also suggested that if a "young gentleman" might try "to influence her vote through his sway over her affection". Mary Ann Walker responded by claiming that "she would treat with womanly scorn, as a contemptible scoundrel, the man who would dare to influence her vote by any undue and unworthy means; for if he were base enough to mislead her in one way, he would in another.” (13)

On 6th November, 1842, The Sunday Observer reported that Susanna Inge was giving a lecture at the National Charter Hall in London. With her was another woman, Emma Matilda Miles. The newspaper suggested that the women had joined in response to the arrest and punishment of John Frost after the Newport Uprising. It would seem that Inge was a supporter of the Physical Force movement. (14)

Susanna Inge was not content to be a mere propagandist. She had ideas on how Chartism might be better organised. In one letter to the The Northern Star she suggested that every Chartist locality should have its byelaws and plan of organisation hung in a prominent place, that these should be read before every meeting, and that any officer who failed to abide by them should be called to account. (15)

Feargus O'Connor, the leader of the Physical Force chartists, was not in favour of women having equal political rights with men. He claimed that the role of the woman was to be a "housewife to prepare meals, to wash, to brew, and look after my comforts, and the education of my children." (16) Anna Clark has pointed out that O'Connor demanded "entry into the public sphere for working men" and "the privileges of domesticity for their wives". (17)

Susanna Inge wrote letters to O’Connor's newspaper complaining about his views. These were rejected for publication and in July, 1843, it admitted that Inge "very much questions the propriety or right of Mr O’Connor to name or suggest to the people, through the medium of the Northern Star, any person to fill any office whatever" as "it is not according to her ideas of democracy." The newspaper dismissed her comments with the words: "We dare say Miss Inge is greatly in love with her ideas of democracy; and so she ought, for we fancy they will suit nobody else” (18)

Women Activists

One of the most militant women's groups was the Female Political Union of Newcastle. They completely rejected the idea that they should not become involved in politics. "We have been told that the province of women is her home, and that the field of politics should be left to men; this we deny. It is not true that the interests of our fathers, husbands, and brothers, ought to be ours? If they are oppressed and impoverished, do we not share those evils with them? If so, ought we not to resent the infliction of those wrongs upon them? We have read the records of the past, and our hearts have responded to the historian's praise of those women, who struggled against tyranny and urged their countrymen to be free or die." (19)

In 1840, R. J. Richardson, a Chartist from Salford, wrote the pamphlet, The Rights of Women, while he was in Lancaster Prison. "If a woman is qualified to be a queen over a great nation, armed with power of nullifying the powers of Parliament. If it is to be admissible that the queen, a woman, by the constitution of the country can command, can rule over a nation, then I say, women in every instance ought not to be excluded from her share in the executive and legislative power of the country." (20)

William Lovett argued that women's rights should be equal to those of men. However, Lovett added that woman's duties were different from that of her male partner. "His being to provide for the wants and necessaries of the family; hers to perform the duties of the household." However, when in March 1841, Lovett, Henry Hetherington and Henry Vincent, launched the National Association, the new organisation included women's suffrage in their programme. (21)

It has been estimated that up to 20% of those who signed Chartist petitions were women. As well as holding meetings they fully participated at open-air rallies. Henry Vincent reports that when he was addressing a meeting in Cirencester he was pelted with stones. A group of local women gave one of the culprits "a good thrashing". A similar incident involving an anti-Chartist heckler occurred at Stockton-upon-Tees, and women also "occasionally featured among Chartists charged with public order offences." (22)

William Pattison, a leading Chartist in Scotland, explained that it was very difficult for women to play an active role in politics: “He knew that the females were maligned, more perhaps than any other party, for taking a part in politics. He did assure them that the position which females ought to occupy, was the duties of home and the family circle. But, under the present system of legislation, instead of being allowed to remain at home, they were forced to go and toil in the factory for their existence.” (23)

The main argument put forward by Chartist women was that their husbands should earn enough to support them and their children at home. Female Chartists were concerned with women and children replacing men in factories. Three leading women chartists, Elizabeth Pease, Jane Smeal and Anne Knight, were all Quakers. These women had also been involved in the anti-slavery campaign.

Pease pointed out in a letter to a friend why she was active in the Chartist movement: "The grand principle of the natural equality of man - a principle alas almost buried, in the land, beneath the rubbish of an hereditary aristocracy and the force of a state religion. Working people are driven almost to desperation by those who consider they are but chattels made to minister to their luxury and add to their wealth." (24)

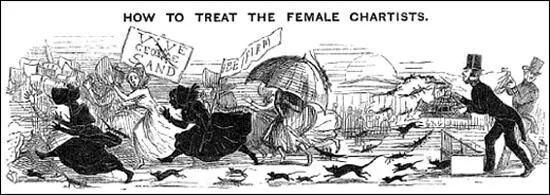

Punch Magazine was a strong opponent of Chartism and ridicled those women demanding the vote. In one article it argued: "London is threatened with an irruption of female Chartists, and every male of experience is naturally alarmed.... We confess we are much more alarmed about the threatened rising of the ladies than we should be by the revolt of half the scamps in the metropolis. The women must be put down, as any unfortunate victim of female domination can testify. How then, are we to deal with the female Chartists? The police will never be got to act against them; for that gallant force knows how much the kitchens are in the hands of the gentler sex, and there is no member of the force who would willingly make himself an outcast from the hearth of the British basement. We have however, something to propose that will easily meet the emergency. A heroise who would never run from a man, would fly in dismay before an industrious flea or a burly black-beatle. We have only to collect together a good supply of cockroaches, with a fair sprinkling of rats, and a muster of mice, in order to disperse the largest and most ferocious crowd of females that ever was collected. (25)

Women who spoke at Chartist meetings were described in the national press as "she-orators". The Sunday Observer reported on a meeting where Emma Matilda Miles told the audience: "It was the duty of women to step forth, and, in all the majesty of her native dignity, assist her brother slaves in effecting the political redemption of the country. It was not ambition, it was not vanity that induced her to become a public woman; no, it was the oppression which had fallen upon every poor man's house that made her speak.... She did not doubt the ultimate success of Chartism any more than she doubted her own existence; but then it would not, as she said, be granted by the justice - no, it must be extorted from the fears of their oppressors". (26)

Anne Knight

Anne Knight was the most outspoken of the women in the movement. She was concerned about the way women campaigners were treated by some of the male leaders in the organisation. Knight criticised them for claiming "that the class struggle took precedence over that for women's rights". (27) Knight wrote "can a man be free, if a woman be a slave." (28) In a letter published in the Brighton Herald in 1850 she demanded that the Chartists should campaign for what she described as "true universal suffrage". (29)

An anonymous leaflet was published in 1847. It has been persuasively argued that the author of the work was Anne Knight. In argued: "Never will the nations of the earth be well governed, until both sexes, as well as all parties, are fully represented and have an influence, a voice, and a hand in the enactment and administration of the laws". (30)

Knight also became involved in international politics. In 1848 she was the first French government elected by universal manhood suffrage repressed freedom of association. The decree prohibited women from forming clubs or attending meetings of associations. Knight published a pamphlet criticising this action: "Alas, my brother, is it then true that thy eloquent voice has been heard in the heart of the National Assembly expressing a sentiment so contrary to real republicanism? Can it be that thou hast really protested not only against women's rights to form clubs but also against their right to attend clubs formed by men?" (31)

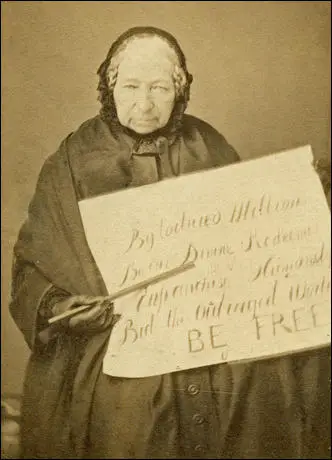

placard reads: "By tortured millions, By the Divine Redeemer,

Enfranchise Humanity, Bid the Outraged World, BE FREE".

At a conference on world peace held in 1849, Anne Knight met two of Britain's reformers, Henry Brougham and Richard Cobden. She was disappointed by their lack of enthusiasm for women's rights. For the next few months she sent them several letters arguing the case for women's suffrage. In one letter to Cobden she argued that it was only when women had the vote that the electorate would be able to pressurize politicians into achieving world peace. (32)

Anne Knight established the Sheffield Female Political Association. Their first meeting was held in Sheffield in February, 1851. Later that year it published an "Address to the Women of England". This was the first petition in England that demanded women's suffrage. It was presented to the House of Lords by George Howard, 7th Earl of Carlisle. (33) The following year she was "forbidden to vote for the man who inflicts the laws I am compelled to obey - the taxes I am compelled to pay". She added that "taxation without representation is tyranny". (34)

Primary Sources

(1) The Charter newspaper (17th October, 1839)

The East London Female Patriotic Association held its usual meeting on Monday evening at the Trades' Hall, Abbey Street. It was resolved to publish the objects and rules of the association as follows:

(1) To unite with our sisters in the country, and to use our best endeavours to assist our brethren in obtaining universal suffrage.

(2) To aid each other in cases of great necessity or affliction.

(3) To assist any of our friends who may be imprisoned for political offences.

(4) To deal as much as possible with those shopkeepers who are favourable to the People's Charter.

(2) Address of the Female Political Union of Newcastle, published in the Northern Star, (2nd Feb, 1839)

We have been told that the province of women is her home, and that the field of politics should be left to men; this we deny. It is not true that the interests of our fathers, husbands, and brothers, ought to be ours? If they are oppressed and impoverished, do we not share those evils with them? If so, ought we not to resent the infliction of those wrongs upon them? We have read the records of the past, and our hearts have responded to the historian's praise of those women, who struggled against tyranny and urged their countrymen to be free or die.

For years we have struggled to maintain our homes in comfort, such as our hearts told us should greet our husbands after their fatiguing labours. Year after year has passed away, and even now our wishes have no prospect of being realised, our husbands are over-wrought, our houses half furnished, our families ill-fed, and our children uneducated. We are a despised caste; our oppressors are not content with despising our feelings, but demand the control of our thoughts and wants! We are oppressed because we are poor - the joys of life, the gladness of plenty, and the sympathies of nature, are not for us; the solace of our homes, the endearments of our children, and the sympathies of our kindred are denied us - and even in the grave our ashes are laid with disrespect.

(3) R. J. Richardson, The Rights of Women (1840)

If a woman is qualified to be a queen over a great nation, armed with power of nullifying the powers of Parliament. If it is to be admissible that the queen, a woman, by the constitution of the country can command, can rule over a nation, then I say, women in every instance ought not to be excluded from her share in the executive and legislative power of the country.

If women be subject to pains and penalties, on account of that infringement of any laws or laws - even unto death - in the name of common justice, she ought to have a voice in making the laws she is bound to obey.

It is a most introvertive fact, that women contribute to the wealth and resources of the kingdom. Debased is the man who would say women have no right to interfere in politics, when it is evident, that they have as much right as a man.

(4) Statement issued by the Female Chartists of Aberdeen (12th November, 1841)

While we are compelled to share the misery of our fathers, our husbands, our brothers, and our lovers, we are determined to have a share in their struggles to be free, and to cheer them in their onward march for liberty.

(5) The Sunday Observer, (6th November, 1842)

The She-Chartists mustered on Tuesday night in numbers stronger than usual at the "National Charter Hall", for the purpose of hearing a lecture upon the principles of liberty, delivered by Miss Inge. From the attendance on Tuesday there can be no doubt that She-Chartism is beginning to make its way among the helpmates of Feargus O'Connor.

Miss Emma Matilda Miles, rather a pretty looking little creature, of some two or three and twenty, and the she-orator rose amidst vociferous cheers to "offer a few remarks". It was the duty of women to step forth, and, in all the majesty of her native dignity, assist her brother slaves in effecting the political redemption of the country. It was not ambition, it was not vanity that induced her to become a public woman; no, it was the oppression which had fallen upon every poor man's house that made her speak.

For herself she would say that ever since the prosecution at Newport of the noble martyrs of Chartism, Frost, Williams and Jones, she had determined to fraternize with the Chartists till the blood should cease to flow in her veins. She did not doubt the ultimate success of Chartism any more than she doubted her own existence; but then it would not, as she said, be granted by the justice - no, it must be extorted from the fears of their oppressors.

(6) Elizabeth Pease, letter to John Collins (14th December, 1840)

I believe there are few persons whose natural feelings are so opposed to women appearing prominently before the public, as mine - but viewed in the light of principle I see, the prejudice - custom and other feelings which will not stand the test of truth, are at the bottom, and must be laid aside.

(7) Elizabeth Pease, letter to Anne Phillips (29th September, 1842)

The grand principle of the natural equality of man - a principle alas almost buried, in the land, beneath the rubbish of an hereditary aristocracy and the force of a state religion. Working people are driven almost to desperation by those who consider they are but chattels made to minister to their luxury and add to their wealth.

(8) Susanna Inge, The Northern Star (2nd July, 1842)

As civilisation advances man becomes more inclined to place woman on an equality with himself, and though excluded from everything connected with public life, her condition is considerably improved... Assist those men who will, nay, who do, place women in on equality with themselves in gaining their rights, and yours will be gained also.

(9) Anne Knight, letter to Matilda Ashurst Biggs (April 1847)

I wish the talented philanthropists in England would come forward in this critical juncture of our nation's affairs and insist on the right of suffrage for all men and women unstained with crime... in order that all may have a voice in the affairs of their country... Never will the nations of the earth be well governed until both sexes, as well as all parties, are fully represented, and have an influence, a voice, and a hand in the enactment and administration of the laws.

(10) Punch Magazine (15th July 1848)

London is threatened with an irruption of female Chartists, and every male of experience is naturally alarmed.... We confess we are much more alarmed about the threatened rising of the ladies than we should be by the revolt of half the scamps in the metropolis. The women must be put down, as any unfortunate victim of female domination can testify.

How then, are we to deal with the female Chartists? The police will never be got to act against them; for that gallant force knows how much the kitchens are in the hands of the gentler sex, and there is no member of the force who would willingly make himself an outcast from the hearth of the British basement. We have however, something to propose that will easily meet the emergency. A heroise who would never run from a man, would fly in dismay before an industrious flea or a burly black-beatle. We have only to collect together a good supply of cockroaches, with a fair sprinkling of rats, and a muster of mice, in order to disperse the largest and most ferocious crowd of females that ever was collected. We respectfully submit our proposition to Sir George Grey, as a certain specific for allaying female turbulence.

(11) Anne Knight, letter published in the Brighton Herald (9th February, 1850)

It is justice that we demand for all who bear their share in the burdens of the State, and who does not pay taxes in this miserably tax-ground country? Is she exempt whose part it is to work 18 hours out of 24, to sleep little, and to be too much worn with labour to think.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)