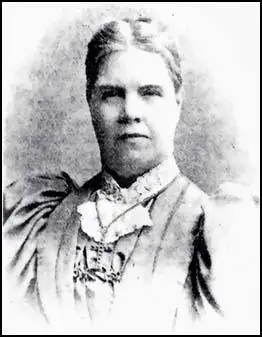

Emma Gifford Hardy

Emma Gifford, the daughter of solicitor, John Attersoll Gifford and Emma Farman Gifford, was born in Plymouth, on 24th November 1840. Emma was the youngest of five children. She later recalled that her home was "a most intellectual one and not only so but one of exquisite home-training and refinement - alas the difference the loss of these amenities and generalities has made to me."

In 1860 Emma's wealthy grandmother, Helen Gifford, died. The family then moved to the grandmother's property in Bodmin, Cornwall. On 7th March 1870, she met Thomas Hardy, who had been sent to St. Juliot near Boscastle, by his employer, in order "to take a plan and particulars of a church I am about to rebuild there". She later recalled that Hardy had a beard and was wearing "a rather shabby great coat". Hardy fell in love with Emma and he returned to the village every few months. During this period Emma was described as having "a rosy, Rubenesque complexion, striking blue eyes and auburn hair with ringlets reaching down as far as her shoulders".

Robert Gittings, the author of The Young Thomas Hardy (2001) has argued: "Emma Lavinia Gifford certainly appears... as the spoilt child of a spoilt father. There is no doubt at all that wilfulness and lack of restraint gave her a dash and charm that captivated Hardy from the moment they met. He did not consider, any more than most men would have done, that a childish impulsiveness and inconsequential manner, charming at thirty, might grate on him when carried into middle age."

Hardy's novel, Under the Greenwood Tree was published by Tinsley Brothers in June 1872. After good reviews in the Pall Mall Gazette and The Athenaeum, it was agreed to serialise the novel over a period of twelve months in the Tinsley's Magazine. This gave Hardy a guaranteed income over the next year and he decided he could take the risk of becoming a full-time writer. Emma Gifford, despite the objections of her father, agreed to marry Hardy.

Leslie Stephen, the editor of The Cornhill Magazine, had been impressed by Hardy's Under the Greenwood Tree and asked him to provide a story suitable for serialisation in the magazine. Hardy accepted the offer and began work on a story that had been told to him by his former girlfriend, Tryphena Sparks. It tells of a woman who has inherited a farm, which contrary to the tradition of the times she insists on managing herself.

Far From the Madding Crowd is the story of a young woman-farmer, Bathsheba Everdene, and her three suitors: Gabriel Oak, a young man who owns a small sheep farm. Sergeant Frank Troy, a well-educated, young soldier who has a reputation as a womaniser. William Boldwood, a local farmer who develops a strong passion for Bathsheba. Leslie Stephen was shocked by the sexual content of the novel and asked for Hardy to make some changes, admitting that this was the result of "an excessive prudery of which I am ashamed."

The novel was serialised between January and December 1874. After receiving £400 by its publishers, Thomas Hardy could now afford to marry Emma. The wedding took place on 17th September 1874. Emma's uncle, Dr Edwin Hamilton Gifford, canon of Worcester Cathedral officiated. The only other people present being Emma's brother, Walter E. Gifford and Sarah Williams, the daughter of Hardy's landlady, who signed the register as a witness. Hardy's parents, may have also objected to the marriage because they were not invited to the ceremony.

After spending a few days in Brighton they travelled to Paris, where Hardy insisted on visiting the city mortuary where he looked at several dead bodies. Emma wrote in her diary that she found the experience "repulsive". According to the author of Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011): "The visit to the Paris mortuary had led to speculation that Hardy may have had a tendency to necrophilia (a morbid, and in particular an erotic, attraction to corpses)".

In 1883 the Hardys moved to a rented house in Dorchester. Hardy commissioned his father and brother to build a new house just outside the town, on a plot of open downland on the road to Wareham. Called Max Gate, the red-brick building was completed in June 1885. Hardy planted over 2,000 trees around it to give him greater privacy. However, he wrote in his diary at the end of the year that he was "sadder than many previous New Year's Eves have done." He also said that the building of his new home was not "a wise expenditure of energy".

Hardy's novel The Woodlanders, was published in 1886. He wrote in the novel's preface that the book is principally concerned with the "question of matrimonial divergence, the immortal puzzle of how a couple are to find a basis for their sexual relationship". He then adds that a problem may arise when a person "feels some second person to be better suited to his or her tastes than the one whom he has contracted to live". It has been argued that the book deals with Hardy's relationship with his wife.

Andrew Norman, the author of Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011) has pointed out: "In The Woodlanders, many of Hardy's favourite themes resurface. They include the problems encountered when two persons of different social status fall in love, and when two men compete with one another for the hand of one woman, together with the problems men and women may have of understanding one another. Hardy also stresses that qualities such as loyalty, devotion and steadfastness in a male suitor, ought always to triumph over wealth, property and title."

Tess of the D'Urbervilles was published in November 1891. Several libraries refused to stock the book but the controversy about the content helped it to become a best-seller. It was also translated into several different languages. Hardy was upset with the reviews that the book received that he said to a friend that "if this sort of thing continues" there would be "no more novel writing for me."

Despite these comments, Thomas Hardy now began work on what was to be his most controversial book, Jude the Obscure. Following the death of his parents, Jude Fawley, is brought up by a great aunt, who, along with his schoolmaster, Phillotson, encouraged him to get a university education at Christminster (Oxford). However, before he can do this he is tricked into marrying Arabella Donn, the daughter of a pig breeder.

Arabella eventually deserts Jude and goes to live in Australia. Jude moves to Christminster where he obtains employment as a stonemason, while continuing to study part-time. Unfortunately, his application to study at the university is rejected.

While in Christminster he becomes friendly with his cousin, Sue Bridehead. He introduces her to Phillotson, whom she subsequently marries. However, the marriage is not a success and as she is so unhappy, Phillotson agrees to give Sue a divorce. For this act of compassion, Phillotson is dismissed from his post as schoolmaster.

Sue goes to live with Jude and they consider getting married. Jude is dissatisfied with Sue because she is "such a phantasmal, bodiless creature, one who - if you'll allow me to say it - has so little animal passion in you, that you can act upon reason in the matter when we poor unfortunate wretches of grosser substance can't." Jude tells Sue: "People go on marrying because they can't resist natural forces, although many of them may know perfectly well that they are possibly buying a month's pleasure with a life's discomfort."

Jude and Sue eventually agree to get married, but when they arrive at the registrar's office, Sue changes her mind and says to Jude: "Let us go home, without killing our dream". However, they do live together and Sue gives birth to two children. Jude is informed by Arabella that after leaving him she gave birth to his son. She asks him to look after the son, Juey. Jude and Sue agree to this suggestion.

Jude is employed by the local church to inscribe stone tablets. When it is discovered that Jude and Sue are unmarried, he is sacked from his job. Soon afterwards, Juey, hangs Jude's two children by Sue and then hangs himself. Sue regards this as a judgement from God and returns to Phillotson.

In the preface of Jude the Obscure Hardy point out that the novel is about the "tragedy of unfulfilled aims". He then goes onto argue that it was an attempt to confront the issue of "the fret and fever, derision and disaster, that may press in the wake of the strongest passion known to humanity; to tell, without a mincing of words, of a deadly war waged between flesh and spirit." Hardy admitted that the novel was an attack on the marriage laws. He wrote that "a marriage should be dissolvable as soon as it becomes a cruelty to either of the parties - being then essentially and morally no marriage."

Michael Millgate, the author of Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisted (2006) has argued: "Its haunted characters, trapped within an intricately disastrous plot, move restlessly from one unfriendly town to another, loving without fulfillment, striving without achievement. By representing Jude Fawley as encountering persistent persecution in his attempts to gain admission to a Christminster (that is, Oxford) college and share with Sue Bridehead a life outside wedlock, Hardy was deliberately attacking the existing educational system and marriage laws."

Reviewers were shocked by the sexual content of the book and it was described as "Jude the Obscene" and "Hardy the Degenerate". William How, the Bishop of Wakefield announced that he was so appalled by Jude the Obscure that he had thrown the novel into the fire. Hardy responded that there was a long religious tradition of "theology and burning" and suggested "they will continue to be allies to the end". Although the novel sold over 20,000 copies in three months, Hardy was upset by the reviews the book received. He commented that he had reached "the end of prose" and now concentrated on writing poetry.

Hardy admitted to a close friend that the characters, Jude and Sue, were based on himself and his wife Emma. As Andrew Norman has pointed out: "Emma felt the same way as Hardy's fictitious character Sue Bridehead, who confessed that the idea of falling in love held a greater attraction for her than the experience of love itself; that Emma, like Sue, derived a perverse pleasure from seeing her admirers break their hearts over her; that Emma felt the same physical revulsion for Hardy that Sue had felt for Phillotson."

Hardy's biographers have speculated that the marriage was never consummated. Emma Hardy complained that her husband never understood her needs. "I can scarcely think that love proper, and enduring, is in the nature of men. There is ever a desire to give but little in return for our devotion and affection." In a letter she wrote in November, 1894, Emma complained that Hardy "understands only the women he invents - the others not at all."

Emma was particularly upset with his platonic relationship with Florence Henniker. Nor did she like his closeness to his sister, Mary. In a letter written to Mary in February 1896 she claimed: "Your brother has been outrageously unkind to me - which is entirely your fault: ever since I have been his wife you have done all you can to make division between us; also, you have set your family against me, though neither you nor they can truly say that I have ever been anything but just, considerate, and kind towards you all, notwithstanding frequent low insults... You have ever been my causeless enemy - causeless, except that I stand in the way of your evil ambition to be on the same level with your brother by trampling, upon me... doubtless you are elated that you have spoiled my life as you love power of - any kind, but you have spoiled your brother's and your own punishment must inevitably follow - for God's promises are true for ever."

Another source of conflict was Emma devout religious views. Hardy on the other hand gradually lost his religious faith. He wrote to a friend that he had been searching for God for fifty years "and I think that if he had existed I should have discovered him". Emma donated money to various Christian charitable institutions, including the Salvation Army and the Evangelical Alliance. She also paid for religious pamphlets to be printed, which she left in local shops or at the homes of people she visited. She wrote that her objective was to "help to make the clear atmosphere of pure Protestantism in the land to revive us again - in the truth - as I believe it to be".

Emma Hardy especially disliked the anti-religious views expressed in Jude the Obscure. Hardy's biographer, Michael Millgate, has pointed out: "Emma Hardy took personal offence not only at Jude's attack on marriage but also at what she saw as its dark pessimism and irreligiousness... As a professional novelist writing to deadlines, peremptory as to his priorities and impatient of interruptions, he was not easy to live with, and he had failed - had perhaps not sufficiently tried - to resolve the antagonism between his wife and the family he now regularly visited. Emma Hardy, temperamentally restless and impulsive, lacking satisfying occupations and sympathetic friends, grew ever more deeply resentful - and publicly critical - of her husband's self-sufficiency and fame."

Emma Hardy was a supporter of women's suffrage and in 1907 she joined George Bernard Shaw and his wife, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, in a march led by Millicent Garrett Fawcett and the National Union of Suffrage Societies in London.

Several visitors to Max Gate commented on the strange behaviour of Emma Hardy. Florence Emily Dugdale wrote to her friend Edward Clodd in November 1910: "Mrs Hardy seems to be queerer than ever. She has just asked me whether I have noticed how extremely like Crippen, Thomas Hardy is in personal appearance. She added darkly, that she would not be surprised to find herself in the cellar one morning. All this in deadly seriousness."

The writer, Arthur C. Benson met her for the first time in September, 1912. He wrote in his diary: "Mrs Hardy is a small, pretty, rather mincing elderly lady with hair curiously puffed and padded and rather fantastically dressed. It was hard to talk to Mrs Hardy who rambled along in a very inconsequentional way, with a bird-like sort of wit, looking sideways and treating my remarks as amiable interruptions... It gave me a sense of something intolerable the thought of his having to live day and night with the absurd, inconsequent, huffy, rambling old lady. They don't get on together at all. The marriage was thought a misalliance for her, when he was poor and undistinguished, and she continues to resent it... He (Hardy) is not agreeable to her either, but his patience must be incredibly tried. She is so queer, and yet has to be treated as rational, while she is full, I imagine, of suspicions and jealousies and affronts which must be half insane."

Evelyn Evans, a member of the Dorchester Debating Literary and Dramatic Society, was a regular visitor to Hardy's home. She later recalled: "She (Emma Hardy) was considered very odd by the townspeople of Dorchester... Her delusions of grandeur grew more marked. Never forgetting that she was an archdeacon's niece who had married beneath her.. She persuaded embarrassed editors to publish her worthless poems, and intimated that she was the guiding spirit of all Hardy's work."

In one letter Emma Hardy described Hardy as "utterly worthless". Thomas Hardy's assistant, Florence Emily Dugdale, remarked that he "spent long evenings alone in his study, insult and abuse his only enlivenment. It sounds cruel to write like that, and in atrocious taste, but truth is truth, after all."

Christine Wood Homer was another regular visitor to Max Gate. She claims that Emma Hardy "had the fixed idea that she was the superior of her husband in birth, education, talents, and manners. She could not, and never did, recognise his greatness". As she got older he behaviour became stranger: "Whereas at first she had only been childish, with advancing age she became very queer and talked curiously." Emma's cousin, Kate Gifford, wrote to Hardy saying "it must have been very sad for you that her mind became so unbalanced latterly".

On Thomas Hardy's 72nd birthday, he was visited by the poets Henry Newbolt and W. B. Yeats. Newbolt later recalled: "Hardy, an exquisitely remote figures, with the air of a nervous stranger, asked me a hundred questions about my impressions of the architecture of Rome and Venice, from which cities I had just returned. Through this conversation I could hear and see Mrs. Hardy giving Yeats much curious information about two very fine cats... In this situation Yeats looked like an Eastern Magician overpowered by a Northern Witch - and I too felt myself spellbound by the famous pair of Blue Eyes, which surpassed all that I have ever seen."

On 22nd November, 1912, Emma Hardy felt unwell. She was visited by her doctor who pronounced that the illness was not of a serious nature. However, on the morning of 27th November, the maid found her dead in bed. Soon after the funeral, Hardy discovered two "book-length" manuscripts, The Pleasures of Heaven and the Pains of Hell and What I Think of My Husband. After reading them Hardy burnt them in the fire.

Primary Sources

(1) Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisted (2006)

There can be little doubt that Hardy's engagement and eventual marriage to Emma Gifford were in some measure the calculated outcome of a conspiracy - if only of discretion - involving the entire rectory household. But if he was "caught" by Emma, is no less true that he was in the early stage of their courtship entirely captivated by her: he did indeed return from Lyonnesse with "magic" in his eyes. Although Emma was born on 24 November 1840, less than six months after Hardy himself, he probably believed her to be younger. At the 1871 Census her age was entered as only twenty-five when it was in fact thirty, and it is hard to think that she would have told so gross an official lie if she had not been anxious to sustain a deception of every day. At twenty-nine, when Hardy first met her, Emma wore her spectacular and as yet unfaded corn-coloured hair in long ringlets down either side of her face - giving her, as a friend wrote, "the look of the old pictures in Hampton Court Palace" and she made a striking figure as she rode dashingly about the countryside in her "soft deep dark coloured brown habit, longer than to her heels". Writing after Emma's death to the then rector of St. Juliot, Hardy suggested that some of the old parishioners might yet "recall her golden curls & rosy colour as she rode about, for she was very attractive at that time".

(2) Robert Gittings, The Young Thomas Hardy (2001)

Emma Lavinia Gifford, named after her mother and an aunt who died in infancy, was the youngest daughter of John Attersoll Gifford and Emma Farman. though her father's family had originally come from Staines in Middlesex, he and his bride were both Bristolians, and at one time had been brought up in the same street in that city, Norfolk Street in the parish of St. Paul's. Mr. Gifford was the son of a school-master, Richard Ireland Gifford, one of whose early eighteenth-century connections had kept a girls' school at Kingston. His own profession may have prompted his granddaughter's quaintly ingenuous remark that "the scholastic line was always taken at times of declining fortunes"; he himself kept a small private school, described as "French and Commercial", at his home in Norfolk Street. Emma Farman, whom John Attersoll Gifford married ar Raglan, Monmouthshire, on 24 April 1832, came from an old-established Bristol family. Her ancestors had been traders and merchants, and her father, William Farman, was an apparently well-to-do accountant. John Attersoll Gifford had qualified as a solicitor, and had practised in Plymouth for a short time before his marriage. He returned to his native Bristol and practised there for the first five years of his married life, before going back again to Plymouth, where his mother, a Devonshire woman, had moved after her husband's death. Emma Lavinia Gifford, the youngest but one of a family of five, was born there on 24 November 1840; she was therefore a few months younger than Hardy himself. She herself described her childhood home as "a most intellectual one and not only so but one of exquisite home-training and refinement". In her recollections in old age, there are idyllic pictures of family music and singing, of readings and discussions of books. Yet there was a darker side, which even memory could not altogether disguise. Part of this came from a peculiar money situation. John Attersol Gifford was his widowed mother's favourite son. When he rejoined her in Plymouth, she decided to live in the same house with him, contributing her own considerable private income. She not only used this to bring up his children, but, in his youngest daughter's words, "she considered it best that he should give up his profession which he disliked, and live a life of quiet cultivated leisure". One gets the impression, incidentally, that his own wife, a simple character who read nothing except the Bible and East Lynne, did not count for much in this household dominated by the older woman. The awakening came when the latter died in 1860. She had set up a trust, from which her favourite son and his wife were to receive all the interest.

Unfortunately, she had so depleted the capital that there was hardly any left, her estate being sworn at under £1,000. Though still appearing in the Law lists as a solicitor, John Attersoll Gifford had evidently taken his mother's advice, and failed to build up a practice. Money was desperately short; the house had to be sold, and the family moved to the remote district of Bodmin in North Cornwell, where living was cheaper. Even then, Emma and her elder sister had to go out to work as governesses. The sister, Helen Catherine, then became an unpaid companion to an old lady, in whose home she met her husband, the Reverend Caddell Holder. Emma joined her in 1868, and was helping with the duties of the rectory two years later when Thomas Hardy arrived on the scene. As well as poverty, there was an even darker shadow on the Gifford household. In times of crisis, John Attersoll Gifford drank heavily. As his daughter artlessly but frankly put it, "never a wedding, removal or death occurred in the family but he broke out again." The origin of this pattern of outbursts is more than a little puzzling. Its so-called explanation came from his mother, who "sympathised with him in the great sorrow of his life". Her own father, William Davie, had had the reputation of never going to bed sober, so that she may well have felt sympathetic. Her son's alleged sorrow was that he had originally been engaged to his wife's elder sister, a girl of eighteen with beautiful golden hair. She had died of scarlet fever; his drinking habits started then, and continued through his subsequent marriage. Emma was his only child with fair hair like her dead aunt; he used, she said, to stroke it, sighing at the memory. This romantic story, which Emma obviously felt gave her a special place in her father's affections, is perhaps not true. Neither in the St. Paul's parish registers, nor in the Bristol newspapers is there any trace of the death of an elder Farman girl. Though there may be some other explanation, it is at least possible that the story was partly invented by his doting mother to excuse her favourite son's alcoholic outbreaks. Its probable basis is that a younger Farman girl did die, aged fifteen, three weeks before John Attersoll Gifford's marriage. Emma Lavinia Gifford certainly appears, in the light of all this, as the spoilt child of a spoilt father. There is no doubt at all that wilfulness and lack of restraint gave her a dash and charm that captivated Hardy from the moment they met. He did not consider, any more than most men would have done, that a childish impulsiveness and inconsequential manner, charming at thirty, might grate on him when carried into middle age.

(3) Emma Hardy, letter to Mary Hardy (February 1896)

I dare you, or anyone to spread evil reports of me - such as that I have been unkind to your brother, (which you actually said to my face) or that I have "errors" in my mind (which you have also said to me), and I hear that you repeat to others.

Your brother has been outrageously unkind to me - which is entirely your fault: ever since I have been his wife you have done all you can to make division between us; also, you have set your family against me, though neither you nor they can truly say that I have ever been anything but just, considerate, and kind towards you all, notwithstanding frequent low insults.

As you are in the habit of saying of people whom you dislike that they are "mad" you should, and may well, fear, lest the same be said of you... it is wicked, spiteful and most malicious habit of yours.

You have ever been my causeless enemy - causeless, except that I stand in the way of your evil ambition to be on the same level with your brother by trampling, upon me... doubtless you are elated that you have spoiled my life as you love power of - any kind, but you have spoiled your brother's and your own punishment must inevitably follow - for God's promises are true for ever.

You are a witch-like creature and quite equal to any amount of evil-wishing & speaking - I can imagine you, and your mother and sister on your native heath raising a storm on a Walpurgis (the eve of 1st May when witches convene and hold revels with the devil).

(4) Arthur C. Benson, diary entry (September, 1912)

Mrs Hardy is a small, pretty, rather mincing elderly lady with hair curiously puffed and padded and rather fantastically dressed. It was hard to talk to Mrs Hardy who rambled along in a very inconsequentional way, with a bird-like sort of wit, looking sideways and treating my remarks as amiable interruptions... It gave me a sense of something intolerable the thought of his having to live day and night with the absurd, inconsequent, huffy, rambling old lady. They don't get on together at all. The marriage was thought a misalliance for her, when he was poor and undistinguished, and she continues to resent it.... He is not agreeable to her either, but his patience must be incredibly tried. She is so queer, and yet has to be treated as rational, while she is full, I imagine, of suspicions and jealousies and affronts which must be half insane.

(5) Andrew Norman, Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask (2011)

Why, in view of the trauma that he had suffered, did Hardy not simply walk away from Emma and petition for a divorce? There were several possible reasons: one was pride - in that he wished to avoid a scandal, which may have led to him being ostracised by society and shunned by his publisher; also, lie still felt responsible for Emma's welfare, and he could not bear the thought of the upheaval which this would entail, including the disruption to his writing. The over-riding reason, however, may have been that, as will be seen, the vision of Emma as he had once perceived her - the beautiful woman who had transfixed him, perhaps at first sight - had not left him, and it never would. And he would spend the remainder of his days in bewilderment, searching for his lost Emma, and hoping against hope that the vision would return.