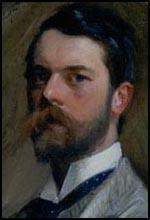

John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent, the eldest surviving child of American parents, Dr Fitzwilliam Sargent (1820–1889) and his wife, Mary Newbold Singer (1826–1906), was born in Florence on 12th January, 1856. His mother came from a very wealthy family in Philadelphia.

He studied painting in Italy and France and in 1884 caused a sensation at the Paris Salon with his painting of of a young socialite named Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau. Exhibited as Madame X, people complained that the painting was provocatively erotic.

His biographers, Elaine Kilmurray and Richard Ormond, have argued: "Its largely hostile reception was one factor spurring his decision to leave Paris for London. Sargent had already been asked to paint members of the Vickers family (connected with the famous armaments firm) in England" Over the next few years he established himself as the country's leading portrait painter. This included portraits of Joseph Chamberlain (1896), Frank Swettenham (1904) and Henry James (1913). Sargent made several visits to the USA where as well as portraits he worked on a series of decorative paintings for public buildings such as the Boston Public Library (1890).

In London he became friends with Henry Tonks and William Rothenstein. He possessed a huge appetite and became corpulent in middle age. Rothenstein pointed out in Men and Memories (1932) that he used to visit "the Hans Crescent Hotel, where, from the table d'hôte luncheon of several courses, he could assuage his Gargantuan appetite".

Sargent became the most important portrait painter of the period and demand very high prices for his work. He received £2,100 for The Ladies Alexandra, Mary, and Theo Acheson (1902), £3,000 for his group of medical doctors Professors Welch, Halsted, Osler and Kelly (1906)and £2,500 for his painting of the Marlborough family.

Sargent spent most of the First World War in the United States. In 1918 Sargent was commissioned to paint a large painting to symbolize the co-operation between British and American forces during the war. Sargent was sent to France with Henry Tonks. One day Sargent visited a casualty clearing station at Le Bac-de-Sud. While at the casualty station he witnessed an orderly leading a group of soldiers that had been blinded by mustard gas. He used this as a subject for a naturalist allegorical frieze depicting a line of young men with their eyes bandaged. Gassed soon became one of the most memorably haunting images of the war. While in France Sargent also painted The Interior of a Hospital Tent (1918) and A Street in Arras (1918).

It has been claimed by Elaine Kilmurray and Richard Ormond: "The impression that emerges from descriptions by his sitters is of a vigorous, decisive, and driven artist. There are stories of Sargent's rushing to and from the easel, totally absorbed, placing his brushstrokes in gestures of absolute precision, of the cries of frustration as he rubbed out, scraped down, reworked, and grappled with the problems of representation, cries punctuated by his mild expletives... Occasionally, he would dash to the piano and play as a brief respite from painting. He was single-minded about what he wanted to achieve and would brook no interference - an approach born of professional self-belief rather than personal arrogance, from which he was remarkably free. He insisted on the right to select his sitters' costumes and accessories, and took brisk exception to comments from his sitters and their families about the truth of the likenesses and characterizations he created."

Cynthia Asquith claims that he was a "curiously inarticulate man, he used to splutter and gasp, almost growl with the strain of trying to express himself; and sometimes, like Macbeth at the dagger, he would literally clutch at the air in frustrated efforts to find, with many intermediary ‘ers’ and ‘ums’, the most ordinary words." Vernon Lee, a very close friend, added: "He was very shy, having I suppose a vague sense that there were poets about… I think John is singularly unprejudiced, almost too amiably candid in his judgements… He talked art & literature, just as formerly, and then, quite unbidden, sat down to the piano and played all sorts of bits of things."

Evan Charteris, the author of John Sargent (1927), has written: "He read no newspapers; he had the sketchiest knowledge of current movements outside art; his receptive credulity made him accept fabulous items of information without question. He would have been puzzled to answer if he were asked how nine-tenths of the population lived, he would have been dumbfounded if asked how they were governed."

John Singer Sargent died in his sleep on 15th April 1925 at home in Tite Street having suffered a heart attack. He was buried in Brookwood Cemetery, Woking, on 18th April.