Iskra Newspaper

In March, 1898, the various groups in Russia who supported the theories of Karl Marx, met in Minsk and decided to form the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP). The party was banned in Russia so most of its leaders were forced to live in exile. This included Lenin, Julius Martov and Alexander Potresov.

Bertram D. Wolfe argued that "Potresov, Lenin and Martov... regarded themselves as the troika: a three-man team that was to lead their generation and became the editorial board of the paper they were planning. While in exile, they had carried on a lengthy correspondence about it; who would write for it; where it would be published; what its position should be on a multitude of questions. The three were so close that Lenin dubbed their union the triple alliance." (1)

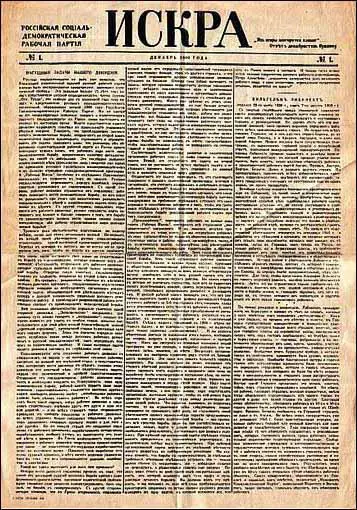

In December, 1900, the SDLP began publishing a newspaper called Iskra (Spark). Its masthead included the words: "Out of this spark will come a conflagration." It was the first underground Marxist paper to be distributed in Russia. It was printed in several European cities and then smuggled into Russia by a network of SDLP agents. The editorial board included Potresov, George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Vera Zasulich, Lenin, Leon Trotsky and Julius Martov. (2)

In the first forty-five issues of the journal Martov wrote thirty-nine articles and Lenin thirty-two; while Plekhanov had done twenty-four, Potresov eight, Zasulich six, Axelrod four and Trotsky two. Rosa Luxemburg and Alexander Parvus also wrote the occasional article. "Lenin and Martov had done all the technical editorial work. Though their emphases and approaches had been distinct, there had been no shadow of political difference." (3)

At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party held in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Lenin and Julius Martov over the future of the SDLP. Alexander Potresov later argued: "At first it seemed to us that we were a group of comrades: that not just ideas united us, but also friendship and complete mutual trust... But the quiet friendship and calm that had reigned in our ranks had disappeared quickly. The person responsible for this change was Lenin. As time went on, his despotic character became more and more evident. He could not bear any opinion different from his own." (4)

Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Leon Trotsky commented that "the split came unexpectedly for all the members of the congress. Lenin, the most active figure in the struggle, did not foresee it, nor had he ever desired it. Both sides were greatly upset by the course of events." (5)

Although Martov won the vote 28-23 on the paragraph defining Party membership, with the support of Plekhanov, Lenin won on almost every other important issue. His greatest victory was over the issue of the size of the Iskra editorial board to three, himself, Plekhanov and Martov. This meant the elimination of Alexander Potresov, Pavel Axelrod and Vera Zasulich - all of whom were "Martov supporters in the growing ideological war between Lenin and Martov". (6)

As Lenin and Plekhanov won most of the votes, their group became known as the Bolsheviks (after bolshinstvo, the Russian word for majority), whereas Martov's group were dubbed Mensheviks (after menshinstvo, meaning minority). Those who became Bolsheviks included Gregory Zinoviev, Anatoli Lunacharsky, Joseph Stalin, Mikhail Lashevich, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Mikhail Frunze, Alexei Rykov, Yakov Sverdlov, Lev Kamenev, Maxim Litvinov, Vladimir Antonov, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Vyacheslav Menzhinsky, Kliment Voroshilov, Vatslav Vorovsky, Yan Berzin and Gregory Ordzhonikidze.

Leon Trotsky supported Julius Martov. So also did Pavel Axelrod, Lev Deich, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Irakli Tsereteli, Moisei Uritsky, Vera Zasulich, Alexander Potresov, Noi Zhordania and Fedor Dan. Trotsky argued in My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1930): "How did I come to be with the 'softs' at the congress? Of the Iskra editors, my closest connections were with Martov, Zasulich and Axelrod. Their influence over me was unquestionable. Before the congress there were various shades of opinion on the editorial board, but no sharp differences. I stood farthest from Plekhanov, who, after the first really trivial encounters, had taken an intense dislike to me. Lenin's attitude towards me was unexceptionally kind. But now it was he who, in my eyes, was attacking the editorial board, a body which was, in my opinion, a single unit, and which bore the exciting name of Iskra. The idea of a split within the board seemed nothing short of sacrilegious to me." (7)

Martov refused to serve on the three-man Iskra board as he could not accept the vote of non-confidence in Axelrod, Potresov and Zasulich. Plekhanov tried to restore party harmony by reconstituting the editorial board on its old basis, with the return of Axelrod, Potresov, Martov and Zasulich. (8) Lenin refused and when Plekhanov insisted that there was no other way to restore unity, Lenin handed in his resignation and stated: "I am absolutely convinced that you will come to the conclusion that it is impossible to work with the Mensheviks." (9)

Plekhanov now began to attack Lenin and predicted that in time he would be a dictator. That he would use "the Central Committee everywhere liquidates the elements with which it is dissatisfied, everywhere seats its own creatures and, filling all the committees with these creatures, without difficulty guarantees itself a fully submissive majority at the congress. The congress, constituted of the creatures of the Central Committee, amiably cries Hurrah!, approves all its successful and unsuccessful actions, and applauds all its plans and initiatives." (10)

Another vigorous attack on Lenin came from Trotsky who described him as a "despot and terrorist who sought to turn the Central Committee of the Party into a Committee of Public Safety - in order to be able to play the role of Robespierre." If Lenin ever took power "the entire international movement of the proletariat would be accused by a revolutionary tribunal of moderatism and the leonine head of Marx would be the first to fall under the guillotine." He added that when Lenin spoke of the dictatorship of the proletariat, he really meant "a dictatorship over the proletariat". (11)

Lenin came under attack from the Marxist philosopher, Rosa Luxemburg. In 1904 she published Organizational Questions of the Russian Democracy, where she argued: "Lenin’s thesis is that the party Central Committee should have the privilege of naming all the local committees of the party. It should have the right to appoint the effective organs of all local bodies from Geneva to Liege, from Tomsk to Irkutsk. It should also have the right to impose on all of them its own ready-made rules of party conduct... The Central Committee would be the only thinking element in the party. All other groupings would be its executive limbs." Luxemburg disagreed with Lenin's views on centralism and suggested that any successful revolution that used this strategy would develop into a communist dictatorship. (12)

The SDLP journal, Iskra remained under the control of the Mensheviks so Lenin, with the help of Anatoli Lunacharsky, Lev Kamenev, Vatslav Vorovsky and Gregory Zinoviev, established a Bolshevik newspaper, Vperyod (Forward). Lenin wrote to Essen Knuniyants: "All the Bolsheviks are rejoicing... At last we have broken up the cursed dissension and are working harmoniously with those who want to work and not to create scandals! A good group of contributors has been got together; there are fresh forces... The Central Committee which betrayed us has lost all credit... The Bolshevik Committees are joining together; they have already chose a Bureau and now the organ will completely unite them.... Do not lose heart. We are all reviving now and will continue to revive... Above all be cheerful. Remember, you and I are not so old yet... everything is still before us." (13)

Primary Sources

(1) Bertram D. Wolfe, Three Who Made a Revolution (1948)

Potresov, Lenin and Martov... regarded themselves as the troika: a three-man team that was to lead their generation and became the editorial board of the paper they were planning. While in exile, they had carried on a lengthy correspondence about it; who would write for it; where it would be published; what its position should be on a multitude of questions. The three were so close that Lenin dubbed their union the triple alliance.

(2) Alexander Potresov, Posthumous Miscellany of Works (1937)

At first it seemed to us that we were a group of comrades: that not just ideas united us, but also friendship and complete mutual trust... But the quiet friendship and calm that had reigned in our ranks had disappeared quickly. The person responsible for this change was Lenin. As time went on, his despotic character became more and more evident. He could not bear any opinion different from his own... His opponent would become a personal enemy, in the struggle with whom all tactics were permissible. Vera Zasulich was the first to notice this characteristic in Lenin. At first she detected it in his attitude towards people with different ideas - the liberals, for example. But gradually it began to appear also in his attitude towards his closest comrades... At first we had been a united family, a group of people who had committed themselves to the Revolution. But we had gradually turned into an executive organ in the hands of a strong man with a dictatorial character.

(3) Statement made by the Iskra editorial board (September, 1900)

In undertaking the publication of a political newspaper, Iskra, we consider it necessary to say a few words concerning the objects for which we are striving and the understanding we have of our tasks.

We are passing through an extremely important period in the history of the Russian working-class movement and Russian Social-Democracy. The past few years have been marked by an astonishingly rapid spread of Social-Democratic ideas among our intelligentsia, and meeting this trend in social ideas is an independent movement of the industrial proletariat, which is beginning to unite and struggle against its oppressors, and to strive eagerly towards socialism. Study circles of workers and Social-Democratic intellectuals are springing up everywhere, local agitation leaflets are being widely distributed, the demand for Social-Democratic literature is increasing and is far outstripping the supply, and intensified government persecution is powerless to restrain the movement. The prisons and places of exile are filled to overflowing. Hardly a month goes by without our hearing of socialists “caught in dragnets” in all parts of Russia, of the capture of underground couriers, of the confiscation of literature and printing-presses. But the movement is growing, it is spreading to ever wider regions, it is penetrating more and more deeply into the working class and is attracting public attention to an ever-increasing degree. The entire economic development of Russia and the history of social thought and of the revolutionary movement in Russia serve as a guarantee that the Social-Democratic working-class movement will grow and will, in the end, surmount all the obstacles that confront it.

On the other hand, the principal feature of our movement, which has become particularly marked in recent times, is its state of disunity and its amateur character, if one may so express it. Local study circles spring up and function independently of one another and—what is particularly important—of circles that have functioned and still function in the same districts. Traditions are not established and continuity is not maintained; local publications fully reflect this disunity and the lack of contact with what Russian Social-Democracy has already achieved.

Such a state of disunity is not in keeping with the demands posed by the movement in its present strength and breadth, and creates, in our opinion, a critical moment in its development. The need for consolidation and for a definite form and organisation is felt with irresistible force in the movement itself; yet among Social-Democrats active in the practical field this need for a transition to a higher form of the movement is not everywhere realised. On the contrary, among wide circles an ideological wavering is to be seen, an infatuation with the fashionable “criticism of Marxism” and with “Bernsteinism,” the spread of the views of the so-called “economist” trend, and what is inseparably connected with it—an effort to keep the movement at its lower level, to push into the background the task of forming a revolutionary party that heads the struggle of the entire people. It is a fact that such an ideological wavering is to be observed among Russian Social-Democrats; that narrow practicalism, detached from the theoretical clarification of the movement as a whole, threatens to divert the movement to a false path. No one who has direct knowledge of the state of affairs in the majority of our organisations has any doubt whatever on that score. Moreover, literary productions exist which confirm this. It is sufficient to mention the Credo, which has already called forth legitimate protest; the Separate Supplement to “Rabochaya Mysl” (September 1899), which brought out so markedly the trend that permeates the whole of Rabochaya Mysl; and, finally, the manifesto of the St. Petersburg Self-Emancipation of the Working Class group,[1] also drawn up in the spirit of “economism.” And completely untrue are the assertions of Rabocheye Dyelo to the effect that the Credo merely represents the opinions of individuals, that the trend represented by Rabochaya Mysl expresses merely the confusion of mind and the tactlessness of its editors, and not a special tendency in the progress of the Russian working-class movement.

Simultaneously with this, the works of authors whom the reading public has hitherto, with more or less reason, regarded as prominent representatives of “legal” Marxism are increasingly revealing a change of views in a direction approximating that of bourgeois apologetics. As a result of all this, we have the confusion and anarchy which has enabled the ex-Marxist, or, more precisely, the ex-socialist, Bernstein, in recounting his successes, to declare, unchallenged, in the press that the majority of Social-Democrats active in Russia are his followers.

We do not desire to exaggerate the gravity of the situation, but it would be immeasurably more harmful to close our eyes to it. For this reason we heartily welcome the decision of the Emancipation of Labour group to resume its literary activity and begin a systematic struggle against the attempts to distort and vulgarise Social-Democracy.

The following practical conclusion is to be drawn from the foregoing: we Russian Social-Democrats must unite and direct all our efforts towards the formation of a strong party which must struggle under the single banner of revolutionary Social-Democracy. This is precisely the task laid down by the congress in 1898 at which the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party was formed, and which published its Manifesto.

We regard ourselves as members of this. Party; we agree entirely with the fundamental ideas contained in the Manifesto and attach extreme importance to it as a public declaration of its aims. Consequently, we, as members of the Party, present the question of our immediate and direct tasks as follows: What plan of activity must we adopt to revive the Party on the firmest possible basis?

The reply usually made to this question is that it is necessary to elect anew a central Party body and instruct it to resume the publication of the Party organ. But, in the period of confusion through which we are now passing, such a simple method is hardly expedient.

To establish and consolidate the Party means to establish and consolidate unity among all Russian Social-Democrats, and, for the reasons indicated above, such unity can not be decreed, it cannot be brought about by a decision, say, of a meeting of representatives; it must be worked for. In the first place, it is necessary to work for solid ideological unity which should eliminate discordance and confusion that—let us be frank!—reign among Russian Social-Democrats at the present time. This ideological unity must be consolidated by a Party programme. Secondly, we must work to achieve an organisation especially for the purpose of establishing and maintaining contact among all the centres of the movement, of supplying complete and timely information about the movement, and of delivering our newspapers and periodicals regularly to all parts of Russia. Only when such an organisation has been founded, only when a Russian socialist post has been established, will the Party possess a sound foundation and become a real fact, and, therefore, a mighty political force. We intend to devote our efforts to the first half of this task, i.e., to creating a common literature, consistent in principle and capable of ideologically uniting revolutionary Social-Democracy, since we regard this as the pressing demand of the movement today and a necessary preliminary measure towards the resumption of Party activity.

As we have said, the ideological unity of Russian Social-Democrats has still to be created, and to this end it is, in our opinion, necessary to have an open and all-embracing discussion of the fundamental questions of principle and tactics raised by the present-day “economists,” Bernsteinians, and “critics.” Before we can unite, and in order that we may unite, we must first of all draw firm and definite lines of demarcation. Otherwise, our unity will be purely fictitious, it will conceal the prevailing confusion and binder its radical elimination. It is understandable, therefore, that we do not intend to make our publication a mere storehouse of various views. On the contrary, we shall conduct it in the spirit of a strictly defined tendency. This tendency can be expressed by the word Marxism, and there is hardly need to add that we stand for the consistent development of the ideas of Marx and Engels and emphatically reject the equivocating, vague, and opportunist “corrections” for which Eduard Bernstein, P. Struve, and many others have set the fashion. But although we shall discuss all questions from our own definite point of view, we shall give space in our columns to polemics between comrades. Open polemics, conducted in full view of all Russian Social-Democrats and class-conscious workers, are necessary and desirable in order to clarify the depth of existing differences, in order to afford discussion of disputed questions from all angles, in order to combat the extremes into which representatives, not only of various views, but even of various localities, or various “specialities” of the revolutionary movement, inevitably fall. Indeed, as noted above, we regard one of the drawbacks of the present-day movement to be the absence of open polemics between avowedly differing views, the effort to conceal differences on fundamental questions.

We shall not enumerate in detail all questions and points of subject-matter included in the programme of our publication, for this programme derives automatically from the general conception of what a political newspaper, published under present conditions, should be.

We will exert our efforts to bring every Russian comrade to regard our publication as his own, to which all groups would communicate every kind of information concerning the movement, in which they would relate their experiences, express their views, indicate their needs for political literature, and voice their opinions concerning Social-Democratic editions: in a word, they would thereby share whatever contribution they make to the movement and whatever they draw from it. Only in this way will it be possible to establish a genuinely all-Russian Social-Democratic organ. Only such a publication will be capable of leading the movement on to the high road of political struggle. “Extend the bounds and broaden the content of our propagandist, agitational, and organisational activity”—these words of P. B. Axelrod must serve as a slogan defining the activities of Russian Social Democrats in the immediate future, and we adopt this slogan in the programme of our publication.

We appeal not only to socialists and class-conscious workers, we also call upon all who are oppressed by the present political system; we place the columns of our publications at their disposal in order that they may expose all the abominations of the Russian autocracy.

Those who regard Social-Democracy as an organisation serving exclusively the spontaneous struggle of the proletariat may be content with merely local agitation and working-class literature “pure and simple.” We do not understand Social-Democracy in this way; we regard it as a revolutionary party, inseparably connected with the working-class movement and directed against absolutism. Only when organised in such a party will the proletariat—the most revolutionary class in Russia today - be in a position to fulfil the historical task that confronts it - to unite under its banner all the democratic elements in the country and to crown the tenacious struggle in which so many generations have fallen with the final triumph over the hated regime.

The size of the newspaper will range from one to two printed signatures.

In view of the conditions under which the Russian under ground press has to work, there will be no regular date of publication.

We have been promised contributions by a number of prominent representatives of international Social-Democracy, the close co-operation of the Emancipation of Labour group (G. V. Plekhanov, P. B. Axelrod, and V. I. Zasulich), and the support of several organisations of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party, as well as of separate groups of Russian Social-Democrats.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Abdication of Tsar Nicholas II (Answer Commentary)

The Provisional Government (Answer Commentary)

The Kornilov Revolt (Answer Commentary)

The Bolsheviks (Answer Commentary)

The Bolshevik Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject