John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck, the son of John Ernst Steinbeck, was born in Sainas, California on 27th February, 1902. His mother, Olive Hamilton Steinbeck, a former school teacher, encouraged her son's passion for reading and writing. He spent his summers working on nearby ranches with migrant workers. This gave him a great sympathy of the underdog.

Steinbeck studied marine biology at Stanford University in Palo Alto. In his spare-time he worked as a agricultural labourer while writing novels and in 1929 published Cup of Gold, based on the life and death of Henry Morgan. The following year he married Carol Henning. The couple lived in a cottage owned by his father in Pacific Grove. Steinbeck also spent time with the artistic community based in Carmel. This included Lincoln Steffens, Ella Winter, Albert Rhys Williams, Robinson Jeffers, Harry Leon Wilson and Marie de L. Welch. Winter described Steinbeck as "excessively shy, a red-faced, blue-eyed giant."

Steinbeck published a collection of short stories portraying the people in a farm community, The Pastures of Heaven (1932) and a novel about a farmer, To a God Unknown (1933). This was followed by Tortilla Flat (1935), that was set in nearby Monterey. With the proceeds of this novel he built a summer ranch-home in Los Gatos.

The journalist, Lincoln Steffens, was very impressed by his next novel, In Dubious Battle. He wrote to his friend, Sam Darcy on 25th February, 1936: "His novel is called In Dubious Battle, the story of a strike in an apple orchard. It's a stunning, straight, correct narrative about things as they happen. Steinbeck says it wasn't undertaken as a strike or labor tale and he was interested in some such theme as the psychology of a mob or strikers, but I think it is the best report of a labor struggle that has come out of this valley. It is as we saw it last summer. It may not be sympathetic with labor, but it is realistic about the vigilantes."

During this period Steinbeck showed great concern for those suffering from the Great Depression. In 1936 he wrote an article on the subject of the Dust Bowl: "Here, in the faces of the husband and his wife, you begin to see an expression you will notice on every face; not worry, but absolute terror of the starvation that crowds in against the borders of the camp.... This is a family of six; a man, his wife and four children. They live in a tent the colour of the ground. Rot has set in on the canvas so that the flaps and the sides hang in tatters and are held together with bits of rusty bailing wire. There is one bed in the family and that is a big tick lying on the ground inside the tent. They have one quilt and a piece of canvas for bedding. The sleeping arrangement is clever. Mother and father lie down together and two children lie between them. Then, heading the other way, the other two children lie, the littler ones."

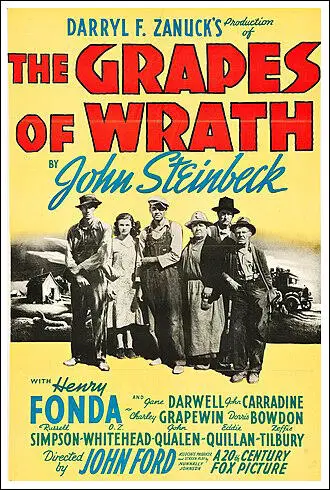

Other books by Steinbeck included Of Mice and Men (1937), The Long Valley (1938) and his best-known novel, The Grapes of Wrath (1939). This novel of a family fleeing from the dust bowl of Oklahoma was made into a film directed by John Ford and featuring Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, John Carradine, Shirley Mills, John Qualen and Eddie Quillan. The book also won Steinbeck the Pulitzer Prize in 1940.

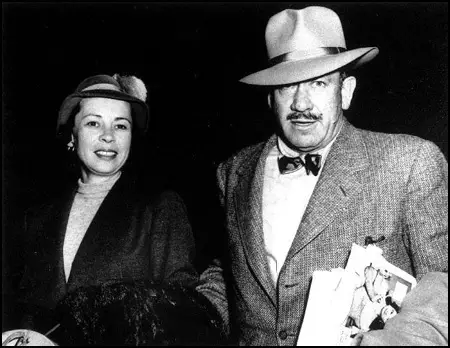

Steinbeck became estranged from Carol Henning in 1941 and they divorced the following year. He married Gwyndolyn Conger in 1942 and over the next few years the couple had two children Thomas Myles Steinbeck (1944) and John Steinbeck IV (1946 - 1991). He later married Elaine Scott, the former wife of Zachary Scott.

During the Second World War Steinbeck went to Europe where he reported the war for the New York Tribune. He also published The Moon is Down (1942), a novel about the resistance in Norway to the Nazi occupation. Steinbeck accompanied commando raids against German-held islands in the Mediterranean. In 1944, wounded by a close munitions explosion in North Africa.

Other books by Steinbeck include Cannery Row (1945), The Pearl (1947), A Russian Journal (1948), Burning Bright (1950), East of Eden (1952), Sweet Thursday (1954), The Short Reign of Pippin IV (1957) and a selection of his writings as a war correspondent, Once There Was a War (1958) and Winter of our Discount (1961).

John Steinbeck, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1962, died in New York City on 20th December, 1966, of heart disease and congestive heart failure. A lifelong smoker, an autopsy showed nearly complete occlusion of the main coronary arteries.

Primary Sources

(1) Lincoln Steffens, letter toSam Darcy (25th February, 1936)

His novel is called In Dubious Battle, the story of a strike in an apple orchard. It's a stunning, straight, correct narrative about things as they happen. Steinbeck says it wasn't undertaken as a strike or labor tale and he was interested in some such theme as the psychology of a mob or strikers, but I think it is the best report of a labor struggle that has come out of this valley. It is as we saw it last summer. It may not be sympathetic with labor, but it is realistic about the vigilantes.

(2) John Steinbeck, Death in the Dust (1936)

Here, in the faces of the husband and his wife, you begin to see an expression you will notice on every face; not worry, but absolute terror of the starvation that crowds in against the borders of the camp. This man has tried to make a toilet by digging a hole in the ground near his house and surrounding it with an old piece of burlap. But he will only do things like that this year. He is a newcomer and his spirit and his decency and his sense of his own dignity have not been quite wiped out. Next year he will be like his next-door neighbour.

This is a family of six; a man, his wife and four children. They live in a tent the colour of the ground. Rot has set in on the canvas so that the flaps and the sides hang in tatters and are held together with bits of rusty bailing wire. There is one bed in the family and that is a big tick lying on the ground inside the tent. They have one quilt and a piece of canvas for bedding. The sleeping arrangement is clever. Mother and father lie down together and two children lie between them. Then, heading the other way, the other two children lie, the littler ones.

If the mother and father sleep with their legs spread wide, there is room for the legs of the children. And this father will not be able to make a maximum of $400 a year anymore because he is no longer alert; he isn't quick at piecework, and he is not able to fight clear of the dullness that has settled on him.

The dullness shows in the faces of this family, and in addition there is a sullenness that makes them taciturn. Sometimes they still start the older children off to school, but the ragged little things will not go; they hide themselves in ditches or wander off by themselves until it is time to go back to the tent, because they are scorned in the school. The better-dressed children shout and jeer, the teachers are quite often impatient with these additions to their duties, and the parents of the "nice" children do not want to have disease carriers in the schools.

The father of this family once had a little grocery store and his family lived in back of it so that even the children could wait on the counter. When the drought set in there was no trade for the store anymore. This is the middle class of the squatters' camp. In a few months this family will slip down to the lower class. Dignity is all gone, and spirit has turned to sullen anger before it dies.

(3) John Steinbeck covered the landings at Salerno in Italy. One of his reports appeared in the New York Tribune on 9th September 1943.

There are little bushes on the sand dunes at Red Beach south of the Sele River, and in a hole in the sand buttressed by sand bags a soldier sat with a leather-covered steel telephone beside him. His shirt was off and his back was dark with sunburn. His helmet lay in the bottom of the hole and his rifle was on a little pile of brush to keep the sand out of it. He had staked a shelter half on a pole to shade him from the sun, and he had spread bushes on top of that to camouflage it. Beside him was a water can and an empty "C" ration can to drink out of.

The soldier said. "Sure you can have a drink. Here, I'll pour it for you." He tilted the water can over the tin cup. "I hate to tell you what it tastes like," he said, I took a drink. "Well, doesn't it?" he said. "It sure does," I said. Up in the hills the 88s were popping and the little bursts threw sand about where they hit, and off to the seaward our cruisers were popping away at the 88s in the hills.

The soldier slapped at a sand fly on his shoulder and then scratched the place where it had bitten him. His face was dirty and streaked where the sweat had run down through the dirt, and his hair and his eyebrows were sunburned almost white. But there was a kind of gayety about him. His telephone buzzed and he answered it, and said, "Hasn't come through yet. Sir, no sir. I'll tell him." He clicked off the phone.

"When'd you come ashore?" he asked. And then without waiting for an answer he went on. "I came in just before dawn yesterday. I wasn't with the very first, but right in the second." He seemed to be very glad about it. "It was hell," he said, "it was bloody hell." He seemed to be gratified at the hell it was, and that was right. The great question had been solved for him. He had been under fire. He knew now what he would do under fire. He would never have to go through that uncertainty again. "I got pretty near up to there," he said, and pointed to two beautiful Greek temples about a mile away. "And then I got sent back here for beach communications. When did you say you got ashore?" and again he didn't wait for an answer.

"It was dark as hell," he said, "and we were just waiting out there." He pointed to the sea where the mass of the invasion fleet rested. "If we thought we were going to sneak ashore we were nuts," he said. "They were waiting for us all fixed up. Why, I heard they had been here two weeks waiting for us. They knew just where we were going to land. They had machine guns in the sand dunes and 88s on the hills.

"We were out there all packed in an LCI and then the hell broke loose. The sky was full of it and the star shells lighted it up and the tracers crisscrossed and the noise - we saw the assault go in, and then one of them hit a surf mine and went up, and in the light you could see them go flying about. I could see the boats land and the guys go wiggling and running, and then maybe there"d be a lot of white lines and some of them would waddle about and collapse and some would hit the beach.

"It didn't seem like men getting killed, more like a picture, like a moving picture. We were pretty crowded up in there though, and then all of a sudden it came on me that this wasn't a moving picture. Those were guys getting the hell shot out of them, and then I got kind of scared, but what I wanted to do mostly was move around. I didn't like being cooped up there where you couldn't get away or get down close to the ground.

(4) John Steinbeck, Once There Was A War (1958)

28th June, 1943: The The crew of the Mary Ruth ends up at a little pub, overcrowded and noisy. They edge their way in to the bar, where the barmaids are drawing beer as fast as they can. In a moment this crew has found a table and they have the small glasses of pale yellow fluid in front of them. It is curious beer. Most of the alcohol has been taken out of it to make munitions. It is not cold. It is token beer - a gesture rather than a drink.

The bomber crew is solemn. Men who are alerted for operational missions are usually solemn, but tonight there is some burden on this crew. There is no way of knowing how these things start. All at once a crew will feel fated. Then little things go wrong. Then they are uneasy until they take off for their mission. When the uneasiness is running it is the waiting that hurts.

They sip the flat, tasteless beer. One of them says, "I saw a paper from home at the Red Cross in London." It is quiet. Theothers look at him across their glasses. A mixed group of pilots and ATS girls at the other end of the pub have started a song. It is astonishing how many of the songs are American. "You'd Be So Nice to Come Home to," they sing. And the beat of the song is subtly changed. It has become an English song.

The waist gunner raises his voice to be heard over the singing. "It seems to me that we are afraid to announce our losses.It seems almost as if the War Department was afraid that the country couldn't take it. I never saw anything the country couldn't take."

(5) John Steinbeck, Once There Was A War (1958)

6th July, 1943: Dover, with its castle on the hill and its little crooked streets, its big, ugly hotels and its secret and dangerous offensive power, is closest of all to the enemy. Dover is full of the memory of Wellington and of Napoleon, of the time when Napoleon came down to Calais and looked across the Channel at England and knew that only this little stretch of water interrupted his conquest of the world. And later the men of Dunkerque dragged their weary feet off the little ships and struggled through the streets of Dover.

Then Hitler came to the hill above Calais and looked across at the cliffs, and again only the little stretch of water stopped the conquest of the world. It is a very little piece of water. On the clear days you can see the hills about Calais, and with a glass you can see the clock tower of Calais. When the guns of Calais fire you can see the flash, while with the telescope you can see from the castle the guns themselves, and even tanks deploying on the beach.

Dover feels very close to the enemy. Three minutes in a fast airplane, three-quarters of an hour in a fast boat. Every day or so a plane comes whipping through and drops a bomb and takes a shot or so at the balloons that hang in the air above the town, and every few days Jerry trains his big guns on Dover and fires a few rounds of high explosive at the little old town. Then a building is hit and collapses and sometimes a few people are killed. It is a wanton, useless thing, serving no military, naval, or morale business. It is almost as though the Germans fretted about the little stretch of water that defeated them.

There is a quality in the people of Dover that may well be the key to the coming German disaster. They are incorrigibly, incorruptibly unimpressed. The German, with his uniform and his pageantry and his threats and plans, does not impress these people at all. The Dover man has taken perhaps a little more pounding than most, not in great blitzes, but in every-day bombing and shelling, and still he is not impressed.

(6) John Steinbeck, Once There Was A War (1958)

8th July, 1943: The countryside is quiet. The guns are silent. Suddenly the siren howls. Buildings that are hidden in camouflage belch people, young men and women. They pour out, running like mad. The siren has not been going for thirty seconds when the run is over, the gun is manned, the target spotted. In the control room under ground the instruments have found their target. A girl has fixed it. The numbers have been transmitted and the ugly barrels whirled. Above ground, in a concrete box, a girl speaks into a telephone. "Fire," she says quietly. The hillside rocks with the explosion of the battery. The field grass shakes, and the red poppies shudder in the blast. New orders come up from below and the girl says, "Fire."

The process is machine-like, exact. There is no waste movement and no nonsense. These girls seem to be natural soldiers. They are soldiers, too. They resent above anything being treated like women when they are near the guns. Their work is hard and constant. Sometimes they are alerted to the guns thirty times in a day and a night. They may fire on a marauder ten times in that period. They have been bombed and strafed, and there is no record of any girl flinching.

The commander is very proud of them. He is fiercely affectionate toward his battery. He says a little bitterly, "All right, why don't you ask about the problem of morals? Everyone wants to know about that. I'll tell you - there is no problem."

He tells about the customs that have come into being in this battery, a set of customs which grew automatically. The men and the women sing together, dance together, and, let any one of the women be insulted, and he has the whole battery on his neck. But when a girl walks out in the evening, it is not with one of the battery men, nor do the men take the girls

to the movies. There have been no engagements and no marriages between members of the battery. Some instinct among the people themselves has told them trouble would result. These things are not a matter of orders but of custom.

The girls like this work and are proud of it. It is difficult to see how the housemaids will be able to go back to dusting furniture under querulous mistresses, how the farm girls will be able to go back to the tiny farms of Scotland and the Midlands. This is the great exciting time of their lives. They are very important, these girls. The defense of the country in their area is in their hands.