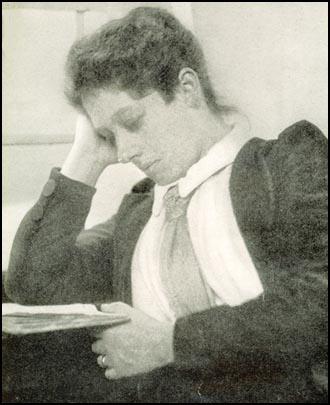

Edith Lees Ellis

Edith Oldham Lees, daughter of Samuel Oldham Lees, a landowner, was born in Cheshire in 1861. She never knew her mother who died soon after she was born, but she worshipped her image and always kept a large photograph of her on her desk.

Phyllis Grosskurth has argued: "Edith's feelings towards her father were very akin to hate... Samuel Lees was choleric, unpredictable, cruel, and he vented his nervous irritability upon his child, leaving her with not only a deep resentment against him but a suspicion of all men. After her mother's death, her father, married a woman who had no capacity to love or comfort the lonely child."

In 1873 Edith was put into a convent at Manchester, where she was happy but when she told her father she wanted to become a Roman Catholic, he immediately moved her to a boarding school in London. She received a "perfunctory sort of education". She met Honor Brooke, the older daughter of Stopford Brooke, the former chaplain of Queen Victoria. However, he eventually rejected the dogmas of the Church of England and became a Unitarian minister at Bedford chapel in Bloomsbury. Brooke introduced her to other radicals. This included Percival Chubb, who became an important figure in her intellectual development. In 1881 Edith inherited a small income of £150 a year.

Edith Lees read Life in Nature by James Hinton, a writer on political, social, religious, and sexual matters. In 1883, Percival Chubb encouraged her to join the Fellowship of the New Life, an organisation founded by Thomas Davidson. Other members included Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis, Edith Nesbit, Frank Podmore, Hubert Bland, Olive Schreiner, Isabella Ford, Henry Hyde Champion, Edward Pease and Henry Stephens Salt. According to another member, Ramsay MacDonald, the group were influenced by the ideas of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In January 1884 some of the members of the group, including Lees, decided to form a socialist debating group. Frank Podmore suggested that the group should be named after the Roman General, Quintus Fabius Maximus, who advocated the weakening the opposition by harassing operations rather than becoming involved in pitched battles. They therefore decided to call themselves the Fabian Society.

By March 1884 the group had twenty members. However, over the next couple of years the group increased in size and included socialists such as Sydney Olivier, William Clarke, Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas, J. A. Hobson, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw, Charles Trevelyan, J. R. Clynes, Harry Snell, Clementina Black, Walter Crane, Sylvester Williams, H. G. Wells, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves.

Edith Lees met Havelock Ellis in 1887 at a meeting of the Fellowship of the New Life. He later recalled: "She was a small, compact, active person, scarcely five feet in height, with a fine skin, a singularly well-shaped head with curly hair, square, powerful hands, very small feet, and - her most conspicuous feature on a first view - large rather pale blue eyes. I cannot say that the impression she made on me on that occasion was specially sympathetic; it so happens that the dominating feature of her face, the pale blue eyes, is not one that appeals to me, for to me green or grey eyes (I believe because one is drawn to those of one's own type) are the congenial eyes, and I never grew really to admire them, though to many they were peculiarly beautiful and fascinating." Edith was also critical of Havelock's appearance. "She (Edith) was not impressed; it seemed to her that my clothes were ill-made, and that was a point on which she always remained sensitive."At the time Ellis was having a relationship with Olive Schreiner. According to his biographer: "Olive was a forceful and passionate woman, though prone to ill health, and the two writers quickly established a fervent relationship. It is not clear whether it was conventionally consummated. Ellis himself appears not to have been strongly drawn to heterosexual intercourse, and had a lifelong interest in urolagnia, a delight in seeing women urinate."

In 1890 Havelock Ellis' first book, The New Spirit, was published. According to one critic, the book discusses "the manifestations of the new spirit abroad in the world: the growing sciences of anthropology, sociology, and political science; the increasing importance of women; the disappearance of war; the substitution of art for religion as a social and emotional outlet." The book was heavily criticised. One reviewer commented that: "His reading has been rather too exclusively among the rebels and heretics of literature; and he would be well advised if he were to restore the balance by devoting more attention to the older, more conservative, more historic writers, whose influence, we may depend upon it, will survive the fame of several of the new men for whom our present-day critics are erecting very lofty pedestals."

Edith Lees later wrote: "When I first read The New Spirit, I knew I loved the man who wrote it." In August, Ellis had a week's work replacing Dr. Bonar at Probus, in Cornwall. While at Lamorna he met Edith Lees who was on holiday at the time. They went for long walks together and talked a great deal about their ideas on politics and religion. Ellis later described their relationship as "a union of affectionate comradeship, in which the specific emotions of sex had the smallest part, yet a union, as I was later to learn by experience, able to attain even on that basis a passionate intensity of love."

They eventually married on 19th December 1891. The relationship was highly unconventional. They maintained separate incomes and, for large parts of the year, separate dwellings. It seems that they did not have a sexual relationship. Havelock Ellis wrote that "on my side I felt that in this respect we were relatively unsuited to each other, that (sexual) relations were incomplete and unsatisfactory". Lees was a lesbian who had relationships with other women. The first relationship was with a woman that Ellis called "Claire" in his autobiography. Phyllis Grosskurth has pointed out: "Edith was to have a succession of passionate relationships, although - and Ellis regarded this as an extenuation - only one intense friend at a time. He learned to accept the succession of dear friends; he never quarrelled with any of them and the only test he applied to them was whether they were good for Edith or not."

According to Lillian Faderman, the author of Surpassing the Love of Men (1985): "Ellis's wife, Edith Lees, seems to have been a victim of his theories. From his own account, Ellis apparently convinced her that she was a congenital invert (lesbian), while she believed herself to be only a romantic friend to other women. He relates in My Life that during the first years of their marriage, she revealed to him an emotional relationship with an old friend who staved with her while she and Ellis were apart... He thus encouraged her to see herself as an invert and to regard her subsequent love relations with women as a manifestation of her inversion."

In his autobiography, My Life (1940), Havelock Ellis claimed: "It was certainly not a union of unrestrainable passion; I, though I failed yet clearly to realise why, was conscious of no inevitably passionate sexual attraction to her, and she, also without yet clearly realising why, had never felt genuinely passionate sexual attraction for any man... Whatever passionate attractions she had experienced were for women."

In 1894 Ellis published Man and Woman: A Study of Human Secondary Sexual Characters. In his autobiography he wrote "it was a book to be studied and read in order to clear the ground for the study of sex in the central sense in which I was chiefly concerned with it". He added that it was "primarily undertaken for my own edification". However, as the author of Havelock Ellis (1980) has pointed out: "Until his marriage to Edith, Olive Schreiner seems to have been the only woman with whom he indulged in sexual intimacies, however unsatisfactory they may have been. In other words, the man who wrote Man and Woman was almost totally inexperienced, and when he departs from physiological description he sounds remarkably naïve."

In 1897 Havelock Ellis published Sexual Inversion, the first of his six volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex. The book was first serious study of homosexuality published in Britain. It was based partly as a result of his awareness of the homosexuality of his wife and friends such as Edward Carpenter. Ellis admitted in his autobiography: "Homosexuality was an aspect of sex which up to a few years before had interested me less than any, and I had known very little about it. But during those few years I had become interested in it. Partly I had found that some of my most highly esteemed friends were more or less homosexual (like Edward Carpenter, not to mention Edith)." According to a letter he wrote to Arthur Symonds, Edith promised to "supply cases of inversion (homosexuality) in women from among her own friends."

Phyllis Grosskurth has argued: "Sexual Inversion was an unprecedented book. Never before had homosexuality been treated so soberly, so comprehensively, so sympathetically. To read it today is to read the voice of common sense and compassion; to read it then was, for the great majority, to be affronted by a deliberate incitement to vice of the most degrading kind.... That such sexual proclivity is not determined by suggestion, accident, or historical conditioning is apparent, he argues, from the fact that it is widespread among animals and that there is abundant evidence of its prevalence among various nations at all periods of history."

As one biographer, Jeffrey Weeks, pointed out: "Ellis's aim was to demonstrate that homosexuality (or inversion, his preferred term) was not a product of peculiar national vices, or periods of social decay, but a common and recurrent part of human sexuality, a quirk of nature, a congenital anomaly." This idea was repugnant to most people and the book was attacked by most reviewers. The birth-control campaigner, Marie Stopes, described reading it as "like breathing a bag of soot; it made me feel choked and dirty for three months."

In 1898 Edith published her first novel, Seaweed: A Cornish Idyll. Havelock Ellis commented that the novel was "a real work of art, well planned and well balanced, original and daring, the genuinely personal outcome of its author, alike in its humour and its firm, deep grip of the great sexual problems it is concerned with, centering around the relations of a wife to a husband who by accident has become impotent.... it has seemed to me that the story was consciously or unconsciously inspired by her own relations with me and of course completely transformed by the artist's hand into a new shape."

During this period Edith began a relationship with Lily, an artist from Ireland who lived in St. Ives. In his autobiography, My Life, Havelock Ellis pointed out that: "Much as Edith always admired the clean, honest, reliable Englishwoman, there was yet, as I have already indicated, something in that type that was apt to jar on her in intimate intercourse; she craved something more gracious, less prudish, pure by natural instinct rather than by moral principle. In Lily she found the ideal embodiment of all her cravings." He claimed that he did not mind Edith's passionate relationship with Lily because Claire had absorbed all his capacity for jealously. Edith was devastated when Lily died from Bright's Disease in June 1903.

Edith Ellis was a regular contributor to The Freewoman. The articles on sexuality created a great deal of controversy. However, they were very popular with the readers of the journal. In February 1912, Ethel Bradshaw, secretary of the Bristol branch of the Fabian Women's Group, suggested that readers formed Freewoman Discussion Circles. Soon afterwards they had their first meeting in London and other branches were set up in other towns and cities.

Some of the talks that took place in the Freewoman Discussion Circles included Edith Ellis (Some Problems of Eugenics), Rona Robinson (Abolition of Domestic Drudgery), C. H. Norman (The New Prostitution), Edmund Haynes (Divorce Reform), Huntley Carter (The Dances of the Stars) and Guy Aldred (Sex Oppression and the Way Out). Other active members included Grace Jardine, Stella Browne, Harry J. Birnstingl, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, Rebecca West, Havelock Ellis, Lily Gair Wilkinson, Françoise Lafitte-Cyon and Rose Witcup.

Harriet Shaw Weaver was one of those who joined the Freewoman Discussion Circle in London. The authors of Dear Miss Weaver (1970) pointed out: "It was a successful group, inaugurated at a meeting of more than eighty people. The numbers increased so fast that at its first meeting-room, at the Suffragette shop, was too small. So was its second, at the Eustace Miles vegetarian restaurant; and its final home was at the Chandos Hall. The programme for the session July to October 1912 included talks on Eugenics by Mrs Havelock Ellis and on Divorce Reform by E.S.P. Haynes. Other subjects were Sex Oppression and the Way Out, Celibacy, Prostitution, and the Abolition of Domestic Drudgery." Rebecca West recalled that at the meetings: "Everyone behaved beautifully - it's like being in Church, except Rona Robinson and myself. Barbara Low has spoken very seriously to me about it."

Edith suffered from poor health in her forties. In March 1916 she suffered from a severe nervous breakdown and entered a local convent nursing home at Hayle in Cornwall. Soon afterwards she attempted suicide by throwing herself from the fourth floor. Havelock Ellis wrote to Edward Carpenter: "Quite what she was feeling and thinking these last few days I do not know. It was some kind of despair. She has been despondent and self-reproachful as not having lived up to her ideals for some time past, and has lost her faith in things and in her spirit... The condition has been fundamentally neurasthenia, with mental symptoms - distressing loss of will power and helplessness."

Edith was eventually released but was forced back to hospital and died of diabetes in September 1916. Havelock Ellis told Margaret Sanger: She was always a child, and through everything, a very lovable child, to the last. Even friends whom she only made during the last few weeks are inconsolable at her loss." Two years later he arranged for the publication of her James Hinton: a Sketch (1918).

Primary Sources

(1) Phyllis Grosskurth, Havelock Ellis (1980)

Edith was born in 1861 in Cheshire. Her family background was deeply disturbed. The Lees family were "thoroughly Lancashire" in type and character, whereas her mother's family, the Bancrofts, had a Celtic strain which Ellis believed accounted for Edith's vivacity. "The ancestral traits which the child of these stocks inherited were her destiny," Ellis comments. Her mother was sweet and generally loved - or so Edith mythologized her. Edith was born two months prematurely and Ellis always believed that this accounted for her childlike qualities and for the fact that her physical powers of resistance were so low. She never knew the mother who died shortly after her birth, but she worshipped her image and always kept a large photograph of her on her desk.

Edith's feelings towards her father were very akin to hate. Her grandfather, a collier, would chase his wife around the room with a carving knife when in a drunken rage. A self-made man, he acquired a great deal of money, much of which he left to Edith's father, who squandered it in disastrous schemes. Samuel Lees was choleric, unpredictable, cruel, and he vented his nervous irritability upon his child, leaving her with not only a deep resentment against him but a suspicion of all men. After her mother's death, her father married a woman who had no capacity to love or comfort the lonely child.

When she was about twelve she was put into a convent at Manchester, where, responding to the kindness of the nuns, she announced that she wanted to become a Catholic. Her enraged father immediately moved her to a school near London kept by a German lady of frce-thinking opinions. Here she received a perfunctory sort of education, and it is clear that Ellis did not consider her well educated.

For a time Edith ran some sort of girls' school in Sydenham, but she found herself totally incapable of coping with its financial problems and she broke down completely. Almost desperate, she was rescued by Honor Brooke, the older daughter of the Rev. Stopford Brooke, who took her back to their comfortable home in Manchester Square, and here her kind guardian angel gradually nursed her back to health. The Brookes introduced her into cheerful and cultivated society, and it was in their drawing-room that she first met Percival Chubb. They also introduced her to a kindly Harley Street physician, Dr. Birch, but her progress was slow, and night after night, she suffered tortures of loneliness in a little garret room off Manchester Square where she had moved after leaving the Brookes.

At the time of Ellis's fateful meeting with her in August 1890 she seemed the embodiment of the confident New Woman, and her air of competence gave no indication of her basic fragility. Her tiny figure in its crisp shirtwaist was brisk, efficient, and direct. By now she had become secretary of the Fellowship of the New Life, she was giving feminist lectures and contributing to a journal founded by the New Lifers, Seed-Time. The following spring she and Ramsay MacDonald (who was already talking of being Prime Minister some day) were to become joint secretaries of a Fellowship House at 29 Doughty Street, Bloomsbury. She found MacDonald high-handed even then, and he never bothered to contact her again, even when she wrote him a letter of condolence after his wife's death. She described her experiences at Fellowship House in her novel Attainment (1909), in which she depicted Fellowship as hell on earth.

(2) Havelock Ellis, My Life (1940)

I still went to the Fellowship's meetings from time to time and I rarely failed to join in its occasional excursions into the country. It was on one of these that I first saw Edith Lees. She, it appears, asked Chubb who that man was. "That is Havelock Ellis," he replied impressively. But she was not impressed; it seemed to her that my clothes were ill-made, and that was a point on which she always remained sensitive. We were, however, introduced and walked along together for a few minutes, talking of indifferent subjects. She was a small, compact, active person, scarcely five feet in height, with a fine skin, a singularly well-shaped head with curly hair, square, powerful hands, very small feet, and - her most conspicuous feature on a first view - large rather pale blue eyes. I cannot say that the impression she made on me on that occasion was specially sympathetic; it so happens that the dominating feature of her face, the pale blue eyes, is not one that appeals to me, for to me green or grey eyes (I believe because one is drawn to those of one's own type) are the congenial eyes, and I never grew really to admire them, though to many they were peculiarly beautiful and fascinating, "pools of blue-bells," as one friend wrote after her death, "between the gold of the furze in flower"; it was always her beautiful voice that most appealed to me, and when I came to know her more intimately the lovely expressiveness of her eloquent under-lip, as I used to call it. On her side, as I say, the impression was also not specially favourable, if not indeed unfavourable. It so happened that in the course of our walk through a remote district we came upon a little chapel which we entered. In a playful mood I began to toll the bell. This, it appears, rather jarred on her serious humour - more serious than in later life - and she regarded it as a feeble joke in bad taste. We had no further conversation that I recall. Indeed, during the next two or three years I came little in personal contact with her. I remember once going up to shake hands with her just before a meeting of the Fellowship of which she became the secretary in 1889, but nothing more. No doubt I was drifting further and further away from the Fellowship.

(3) Havelock Ellis, letter to Edith Lees (13th June, 1891)

We have never needed any explanations before, and that has always seemed so beautiful to me, and we seemed to understand instinctively. And that is why I've never explained things that perhaps needed explaining. This is specially so about Olive. I have never known anyone who was so beautiful and wonderful, or with whom I could be so much myself, and it is true enough that for years to be married to her seemed to me the one thing in the world that I longed for, but that is years ago. We are sweet friends now and always will be; but to speak in the way you do of a "vital relationship" to her sounds to me very cruel. Because one has loved somebody who did not love one enough to make the deepest human relationship possible, is that a reason why one must always be left alone? I only explain this to show that I am really free in every sense - perhaps freer than you - and that I haven't been so unfair to you as you seem to think. The thing I wanted to tell you about that has been bothering me was this: I had to decide whether it was possible for me to return the passionate love of someone whom I felt a good deal of sympathy with, and even a little passionate towards. She would have left me absolutely free, and it hurt me to have to torture her. But I had no difficulty in deciding; the real, deep and mutual understanding, which to me is more than passion, wasn't there, and the thought I had constantly in my mind was that my feeling towards you, although I do not feel passionate towards you (as I thought you understood), was one that made any other relationship impossible. I wonder if you will understand that.

Now I've got to explain what I feel about our relationship to each other - and that will be all. Perhaps the only thing that needs explaining is about the absence of passionate feeling. I have always told you that I felt so restful and content with you, that the restless, tormenting, passionate feeling wasn't there; and I have seen that you didn't feel passionate towards me, but have said over and over again that you didn't believe in passion. So we arc quite equal, and why should we quarrel about it? Let us just be natural with each other-leaving the other feeling to grow up or not, as it will. It is possible to me to come near you and to show you my heart, and it is possible to you to come near me; and (to me at least) that is something so deep and so rare that it makes personal tenderness natural and inevitable, or at all events right.

In reference to marriage: I said (or meant) that I did not think either you or I were the kind of people who could safely tie ourselves legally to anyone; true marriage, as I understand it, is a union of soul and body so close and so firmly established that one feels it will last as long as life lasts. For people to whom that has come to exist as an everyday fact of their lives, then the legal tie may safely follow; but it cannot come beforehand. I have seen so much of unhappy marriages - which all started happily - and I do not think anything on earth could induce me to tie myself legally to anyone with whom I had not - perhaps for years - been so united in body and soul that separation would be intolerable. Surely, Edith, you, too, understand that you can't promise to give away your soul for life, that you can't promise to love for ever beforehand. Haven't you learnt this from your own experience?

I don't think I've anything more to explain. Now it's your turn, and then we'll have a rest from explaining. I've told you simply and honestly how I stand towards you. I took it for granted before that everything I have said was what you could have said too. Tell me where you don't feel with me, and tell me quite honestly, as I have told you, how you feel towards me. We aren't so young that we need fear to face the naked facts of life simply and frankly. You know how much you are to me - exactly how much. Putting aside Olive, I have never loved anyone so deeply and truly, and with the kind of love that seemed to make everything possible and pure, and even mv relationship to Olive has not seemed so beautiful and unalloyed as my relationship to you. It has seemed to me that we might perhaps go on becoming nearer and nearer, and dearer and dearer, to each other as time went on. My nature isn't of the passionately impetuous kind (though it's very sensuous) and mv affections grow slowly, and die hard, if at all. Even as it is, we shall be dear comrades as long as we live. You have hurt me rather, but I don't mind because there mustn't be anything false, and our relationship is strong enough to bear a good deal of tugging.

(4) Havelock Ellis, My Life (1940)

It may seem to some that the spirit in which we approached marriage was not that passionate and irresistible spirit of absolute acceptance which seems to them the ideal. Yet we both cherished ideals, and we seriously strove to mould our marriage as near to the ideal as our own natures and the circumstances permitted. It was certainly not a union of unrestrainable passion; I, though I failed yet clearly to realise why, was conscious of no inevitably passionate sexual attraction to her, and she, also without yet clearly realising why, had never felt genuinely passionate sexual attraction for any man. Such preliminary conditions may seem unfavourable in a romantic aspect. Yet in the end they proved, as so many conventionally unpromising conditions in my life have proved, I of inestimable value, and I can never be too thankful that I escaped a marriage of romantic illusions. Certainly, I was not a likely subject to fall victim to such a marriage.

The union was thus fundamentally at the outset, what later it became consciously, a union of affectionate comradeship, in which the specific emotions of sex had the smallest part, yet a union, as I was later to learn by experience, able to attain even on that basis a passionate intensity of love. It was scarcely so at the outset, although my letters to her in the early years are full of yearning love and tender solicitude. We were neither of us in our first youth. I was able to look on marriage as an experiment which might, or might not, turn out well. On her part it was, and remained to the end, a unique and profound experience which she never outgrew. Yet had anything happened to prevent the marriage it is not likely that either of us would then have suffered from a broken heart. The most passionate letters I wrote her were, as she realised, not written until some years after marriage. I can honestly say that by a gradual process of increased knowledge and accumulated emotional experience I am far more in love with her to-day than twenty-five years ago.

Yet to both of us our marriage seemed then a serious affair, and with the passing of the years it became even more tremendously serious. She, at heart distrustful of her own powers of attraction, would from time to time be assailed by doubts - though such doubts were in conflict with her more rooted convictions - that she was not my fit mate, that I realised this, and that it might be best if we separated in order to enable me to marry someone else. This was never at any moment my desire. Much as each of us suffered through marriage I have never been convinced that our marriage was a mistake. Even if in some respects it might seem a mistake, it has been my belief, deepened rather than diminished, that in the greatest matters of life we cannot safely withdraw from a mistake but are, rather, called upon to conquer it, and to retrieve that mistake in a yet greater development of life. It would be a sort of blasphemy against life to speak of a relationship which like ours aided great ends as a mistake, even if, after all, it should in a sense prove true that we both died of it at last.

(5) Edith Lees letter to Olive Schreiner (7th July, 1891)

I wish you were here - I want to take your hands and I should like you to kiss me. I have grown to love you, though, long ago, this would have made me smile to think of. I feel you are very beautiful and true and that is why I am writing to you. It is strange, and yet natural too, that you should even care a little for me.

(6) Havelock Ellis, My Life (1940)

That was the first and last time in our life together that any cloud arose from doubt on my part as to her love. I had not been in the faintest degree jealous of Claire, but, rightly or wrongly, as I have said, I had felt that Edith's love for Claire involved a diminished tenderness for me. If it was so my outburst had itself restored my position. I never repeated it, or felt the slightest impulse to repeat it. Thereafter Edith had a succession of intimate women friends, at least one of whom meant very much indeed to her. I never grudged the devotion, though it was sometimes great, which she expended on them, for I knew that it satisfied a deep and ineradicable need of her nature. The only test I applied to them was how far they were good for her. If they suited her - and her first intuitions were not always quite sound - I was not only content but glad. I never had a quarrel with one of them and some of them have been - now more than ever in our community of loss - my own dear friends. It must not, however, for a moment be supposed that these special friends with whom she had had for a time an intimate relationship such as one side of her nature craved were more than few in number. There was a succession of them but each relationship was exclusive while it lasted, which was usually for years, and would have been permanent had circumstances allowed. She was always relentlessly true to her ideals; she loathed promiscuity; she was attracted to purity of character, though by no means to puritanism; any touch of coarseness or of vice was fatal, and produced in her a revulsion of feeling which nipped in the bud one or two relationships.

(7) Rebecca Jennings, A Lesbian History of Britain (2007)

The idea that sexological categories were imposed on unwilling women by a hostile body of "experts" has also been challenged by recent research. Work on the biographical backgrounds of many leading sexologists has suggested a much closer interaction between individual figures and a homosexual or lesbian culture than was previously thought, so that it is difficult to argue that sexological notions of homosexual identity originated with sexologists and not with the homosexual men and women with whom they came into contact. The relationship between sexologist Havelock Ellis and his wife, Edith Lees Ellis, whom he included amongst his case studies of female inverts, has been one focus of discussion on this issue....

However, Liz Stanley has challenged this view, arguing that Havelock Ellis' account cannot be relied upon because of tensions within the marriage and that Edith Lees Ellis's own papers suggest that the category of inversion was not imposed on her unwillingly. In a letter to the sexologist Edward Carpenter, Edith Lees Ellis recounted a conservation she had had with Carpenter's sister, Alice, concerning Edith's sexuality, in which Alice had informed her that there was some debate amongst their acquaintances on the subject.

Edith apparently responded by including a statement on the subject of her own inversion in a public lecture she was giving that week, something which she also did during her 1914 lecture tour of America. Her willingness to discuss her sexuality in the public domain, in terms of inversion, suggests that Edith Lees Ellis was comfortable with this interpretation of her sexuality and, in a subsequent letter to Edward Carpenter, she discussed her feelings for a woman she had been overwhelmingly in love with. This evidence, Stanley argues, demonstrates not only that Edith Lees Ellis found the concept of inversion helpful in making sense of her feelings for other women, but also that she considered another sexologist, Edward Carpenter, himself a homosexual, a supportive friend and coefficient.

(8) Lillian Faderman, Surpassing the Love of Men (1985)

Ellis's wife, Edith Lees, seems to have been a victim of his theories. From his own account, Ellis apparently convinced her that she was a congenital invert, while she believed herself to be only a romantic friend to other women. He relates in My Life that during the first years of their marriage, she revealed to him an emotional relationship with an old friend who staved with her while she and Ellis were apart... He thus encouraged her to see herself as an invert and to regard her subsequent love relations with women as a manifestation of her inversion.