Bertha Newcombe

Bertha Newcombe, the daughter of Samuel Prout Newcombe and his second wife, Hannah Hales Anderton, was born at Priory House, Lower Clapton, Hackney, London, on 17th February 1857. She had three siblings, Ada (1854–1924), Claude (1859–1925), Mabel (1862-1947) and Jessie (1864–1943). Her father was a schoolmaster who ran a school at Priory House and owned a chain of photographic portrait studios trading under the name of The London School of Photography. (1)

Samuel Newcombe was an author of children’s educational books. This included the book, Fireside Facts from the Great Exhibition (1851). (2) He was an amateur artist and a number of the men from her grandmother's side of the family, the Prouts, had been eminent artists in the 19th century e.g. the watercolour artist Samuel Prout (1783-1852), the topographical painter and lithographer John Skinner Prout (1805-1876). (3)

Slade School of Art

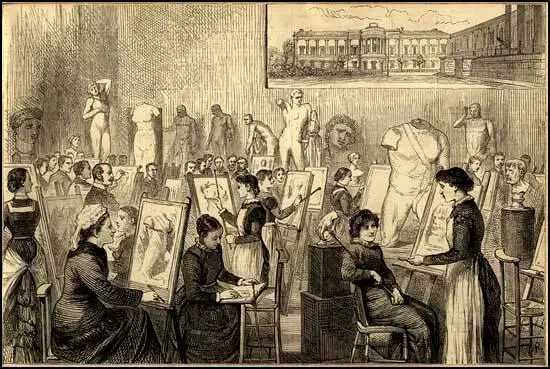

Carrying on the family's artistic tradition Bertha studied at the Slade School of Art. According to Lisa Tickner, the author of The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1987), she arrived at the Slade in 1876. (4) She stayed for several years and in 1881 became friends with Emily Ford. (5) Initially the female students drew from plaster casts of antique classical statues (see below). Later the Slade was the first English art school to offer female students the opportunity to study from living models rather than antique statues. (6)

The inset picture on this illustration shows The Slade School of Fine Art in the

North Wing of London's University College. (1881)

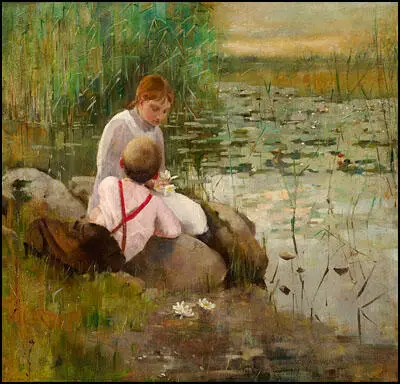

According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018): "Her work received recognition both in Britain and in France, her bucolic pastoral scenes particularly appreciated in the Paris Salons as early as 1881. Bertha Newcombe also had a successful early career as a black-and-white illustrator, producing work for novels and magazines." (7)

At the time of the 1881 Census, Bertha Newcombe was visiting friends in Camberwell, Surrey. The census enumerator records Bertha as a 24-year-old "Artist". In 1881, Bertha's father, mother and two younger sisters, Mabel and Jessie, were boarding at a lodging house in Hastings, Sussex. (8)

Fabian Society and the Society of Female Artists

Bertha held left-wing political views and joined the Fabian Society, the socialist pressure group. She met Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb and by 1884 she was a regular visitor to their home. (9) Beatrice described her in her diary as: "She is petite and dark, about forty years old, but looks more like a wizened girl, than a fully developed woman. Her jet-black hair, heavily fringed, half smart, half artistic clothes, pinched aquiline features and thin lips, give you a somewhat unpleasant impression though not wholly inartistic. She is bad style without being vulgar or common or loud." Beatrice admitted that Kathleen Courtney called her "lady-like" but she believed her to be "insignificant and undistinguished". (10)

Bertha Newcombe also became a supporter of women's suffrage. In 1889 she attended a conference of the Women's Franchise League. She was also a member of the Society of Female Artists (SFA). (11) Other members included Harriet Grote, Elizabeth Thompson and Barbara Bodichon. (12)

The main objective of the SFA was to help women artists get their work exhibited. In March, 1882, "in the two rooms of Society, in Great Marlborough Street, are gathered together some 746 pictures and drawings of all sorts and sizes". It was reported that the paintings by "Miss Bertha Newcombe show considerable promise, and have something of the French style about them." (13)

In February 1886 the Society of Female Artists held its thirty-first exhibition at a new venue, the Drawing Room Gallery at the Egyptian Hall. Bertha Newcombe exhibited several of her paintings. The London Echo commented: "The works exhibited number between five and six hundred, and form a display that is the highest degree creditable to the Society." (14) Bertha also contributed to the Society's exhibition the following year. (15)

Pam Hirsch has pointed out: "The sudden increase in the number of women's paintings exhibited meant that they were inevitably of a variable standard, and some male critics took the opportunity to lament the allegedly low ability of paintings. The SFA gained mixed support from women artists themselves; some who were already successfully exhibiting at the Royal Academy ignored it, and some sent their large historical works to the Royal Academy and smaller works to the SFA." (16)

Bertha Newcombe and George Bernard Shaw

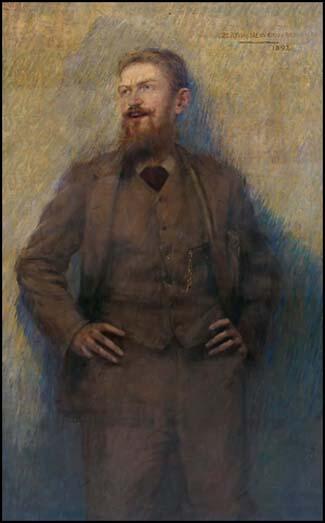

During this period she began a romantic relationship with fellow Fabian member, George Bernard Shaw. She painted his portrait on many occasions. According to Margot Peters: "Shaw had begun to sit for his portrait to a Chelsea artist named Bertha Newcombe at her studio at Cheyne Walk on 14 February 1892. As the portrait progressed so did, inevitably, did the painters fascination with the sitter. On 17 February Shaw gave her a sitting until nine-thirty in the evening and dined with her afterward – she could not let him go home." (17) The painting exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1893. An engraving of the painting was presented to the Fabian Society. (18)

lost but found at Ruskin College and returned to the Labour Party in 2012

In February 1993, Oscar Wilde gave George Bernard Shaw, an inscribed first edition of his book Salome. Such was his relationship with Bertha that he gave it to her in May 1893. (19) Beatrice Webb records in her diary that in April 1895 a group of them spent a week together at Beachy Head. This included Bertha Newcombe, George Bernard Shaw, Sidney Webb, Charles Trevelyan, Graham Wallas and Herbert Samuel. It was a great holiday and Beatrice commented: "What fortunate people we are: Love, Work, Friends and Health, given holidays whenever we need it! An Ideal Life!" (20) It is claimed that it was Beatrice's attempt to bring Newcombe and Shaw together because she did not approve of his relationship with Florence Farr. (21)

Farr was not the only woman in his life Shaw. During this period he had relationships with Edith Nesbit, Annie Besant and Jenny Patterson. Shaw was a socialist who championed the suffragette movement, yet frequently employed misogynist vocabulary in his plays, describing woman as a predatory animal intent on imprisoning her male prey. '"Women have never played an important part in my life," he told a friend once. '"I could always discard them more readily than my friends... women have been a ghastly nuisance." He told Frank Harris: "I was never duped by sex as a basis for permanent relations, nor dreamt of marriage in connection with it... I put everything else before it.." (22)

Bertha began a relationship with Shaw but was disappointed with the way it developed. She later told Ashley Dukes: "Shaw was, I should imagine, by preference a passionless man. He had passed through experiences and he seemed to have no wish for and even to fear passion though he admitted its power and pleasure. The sight of a woman deeply in love with him annoyed him. He was not in love with me, in the usual sense, or at any rate as he said only for a very short time, and he found I think those times the pleasantest when I was the appreciative listener. Unfortunately on my side there was a deep feeling most injudiciously displayed & from this distance I realise how exasperating it must have been to him. He had decided I think on a line of honourable conduct - honourable to his thinking. He kept strictly to the letter of it while allowing himself every opportunity of transgressing the spirit. Frequent talking, talking, talking of the pros & cons of marriage, even to my prospects of money or the want of it, his dislike of the sexual relation & so on, would create an atmosphere of love-making without any need for caresses or endearments. Lovemaking would have been very delightful, doubtless, but I wanted, besides, a wider companionship and as I was inadequately equipped for that, except as a painter of some intelligence, he refused to give more than amusement." (23)

George Bernard Shaw wrote to the actress Janet Achurch that he was romantically involved with Bertha Newcombe. "Everybody seems bent on recommending me to marry Bertha - a fact fatal to her hopes (if it is fair to accuse her of hopes). The feeling, as I understand it, is that there is a fearful danger of my marrying somebody, and that it is perhaps more prudent to pair me with Bertha than to run the risk of my being borne off by someone worse. Now my own view is that since she is neither strong enough nor disorderly enough for a lawless life, nor cold & self-sufficient enough to enjoy a genuinely single one, she ought to marry someone else. She is only wasting her affections on me. I give her nothing; and I do not even take everything - in fact I don't take anything, which makes her most miserable. She has no idea with regard to me except that she would like to tie me like a pet dog to her easel & have me always make love to her when she is tired of painting. And she might just as well feel that way to Cleopatra's needle." (24)

In March 1896 Shaw wrote to Bertha complaining about their relationship. "Your sex likes me as children like wedding cake, for the sake of the sugar on top. If they taste by accident a bit of crumb or citron, it is all over; I am a fiend, delighting in vivisectional cruelties, as indicated by the corners of my mouth." (25) D. A. Hadfield, the author of Shaw and Feminism: On Stage and Off (2016) has commented that this "indicates his inhumane delight, his alleged attraction to cruelty in wooing and then abandoning lovers." (26)

However, it was not until the spring of 1897 that he finally wrote to Bertha to break things off formally. When she received his letter she wrote to Beatrice Webb, whom she suspected of some responsibility for Shaw's change of heart. This was true but his action was also determined by the fact that he had agreed to marry Charlotte Payne-Townshend. (27)

Beatrice decided to visit Bertha: "I felt somewhat uncomfortable as I knew I should encounter a sad soul full of bitterness and loneliness. I stepped into a small wainscoted studio and was greeted coldly by the little woman... I had to explain with perfect frankness that so long as there seemed a chance for her I had been willing to act as chaperone, that she had never been a personal friend of mine or Sidney's that I had regarded her only as Shaw's friend, and that as far as I was concerned I should have welcomed her as his wife. But directly I saw that he meant nothing I backed out of the affair. She took it all quietly, her little face seemed to shrink up and the colour of her skin looked as if it were reflecting the sad lavender of her dress."

Beatrice told Bertha: "You are well out of it, Miss Newcombe... If you had married Shaw he would not have remained faithful to you. You know my opinion of him - as a friend and colleague, as a critic and literary worker, there are few men for whom I have so warm a liking; but in his relations with women he is vulgar, if not worse; it is a vulgarity that includes cruelty and springs from vanity". Bertha replied: "It is so horribly lonely. I daresay it is more peaceful than being kept on the rack, but it is like the peace of death." (28)

During this period she became friends with Thomas Hardy and his wife Emma Hardy. After a visit in March 1900 Bertha wrote to fellow artist, Ellen Epps Goose saying that she had felt much sympathy and pity for the way in which Emma was "struggling against her woes. She asserts herself as much as possible and is a great bore, but at the same time is so kind and goodhearted, and one cannot help realising what she must have been to her husband. She showed us a photograph of herself as a young girl, and it was very attractive." Emma complained she had first met the "ill-grown, under-sized young architect" in Cornwall. Bertha added "I don't wonder... that she resents being slighted by everyone, now that her ugly duckling has grown into such a charming swan. It is so silly of her though isn't it not to rejoice in the privilege of being wife to so great a man?" (29)

Artists' Suffrage League

The Artists' Suffrage League was founded in January 1907 by professional women artists to help with the preparations for the first large-scale public demonstration by the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Its object was "to further the cause of Women's Enfranchisement by the work and professional help of artists... by bringing in an attractive manner before the public eye the long-continued demand for the vote." (30)

The first chairperson of the Artists' Suffrage League was Mary Lowndes, an important stained-glass and poster artist. She designed many of the banners used by the NUWSS including those for the demonstration of 21 June 1908, and for the Women's Pageant of Trades and Professions held the following year at the Albert Hall as part of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance Congress. (31) Bertha Newcombe joined and along with Emily Ford and Dora Meeson Coates, became a member of the Artists' Suffrage League Committee. (32)

The Artists' League organised competitions on behalf of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. As Lisa Tickner has pointed out: "There is some suggestion that competitors needed help in formulating their ideas, and designers were encouraged to send in thumbnail sketches in advance. Even trained artists could be ignorant of the particular requirements of a picture poster, and good designs that would make an impact and reproduce efficiently were difficult to come by." (33)

In 1909 Bertha Newcombe asked George Bernard Shaw to write a play in favour of women's suffrage. He agreed to do this and he wrote a play called Press Cuttings: A Topical Sketch Compiled from the Editorial and Correspondence Columns of the Daily Papers. The play is set on April Fool's Day 1912, by which date the actions of the militant suffragettes are imagined to have led the government to declare martial law in central London. (34)

The play brought Shaw into conflict with the Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household, who had the power to decide which plays would be granted a licence for performance. This meant that Charles Spencer, 6th Earl Spencer, had the capacity to censor theatre at his pleasure. As Shaw pointed out in a letter to The Times, the production ran into problems with the censor as the Prime Minister in the play was called Balsquith and violated "the rule of his department that living persons are not to be represented on the stage… There upon began all the trouble, expense, and loss that the withholding of a license entails. The money paid for the seats had to be returned." (35)

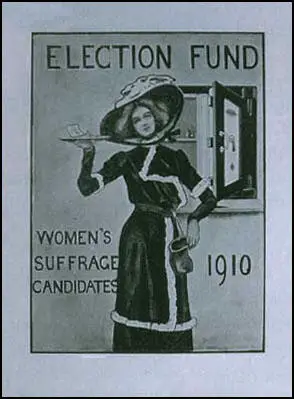

As a member of the Artists' Suffrage League, Bertha Newcombe, produced art-work for the 1910 General Election. The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies were angry with the Liberal Party government that had not kept its promise to give women the vote and decided to raise funds in order to support Labour Party, as the only political party which really supported women's suffrage. (36) Bertha Newcombe agreed to produce a poster for its Election Fighting Fund. (37)

In 1910 Bertha Newcombe painted An Incident in Connection with the Presentation of the First Women's Suffrage Petition to Parliament in 1866. The picture showed Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett hiding first women’s suffrage petition under an apple-woman’s stall in Westminster Hall until John Stuart Mill came to collect it. As a non-militant, Bertha was keen to emphasize the constitutional methods of the suffrage movement "in clear contrast to the revolutionary and satirical suffrage images more commonly seen". (38)

hiding first women’s suffrage petition under an apple-woman’s stall in Westminster Hall

until John Stuart Mill came to collect it. It was entitled An Incident in Connection with the Presentation of the First Women's Suffrage Petition to Parliament in 1866 (1910)

In August 1912, Bertha Newcombe took part in a fund-raising event for the London Society for Women's Suffrage. (39) She remained active in the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies during the First World War. (40)

On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. MPs rejected the idea of granting the vote to women on the same terms as men. Lilian Lenton, who had played an important role in the militant campaign later recalled: "Personally, I didn't vote for a long time, because I hadn't either a husband or furniture, although I was over 30." (41)

The Qualification of Women Act was passed in February, 1918. The Manchester Guardian reported: "The Representation of the People Bill, which doubles the electorate, giving the Parliamentary vote to about six million women and placing soldiers and sailors over 19 on the register (with a proxy vote for those on service abroad), simplifies the registration system, greatly reduces the cost of elections, and provides that they shall all take place on one day, and by a redistribution of seats tends to give a vote the same value everywhere, passed both Houses yesterday and received the Royal assent." (42)

Later Life

In 1921 the 64-year-old Bertha Newcombe was boarding at a large hotel at 7-9 Victoria Road, Kensington, London, W8. (43) When the General Register of 1939 was compiled, Bertha Newcombe was living with her younger sister Mabel Newcombe at Redlynch, Tilmore, Petersfield, Hampshire. (44)

Bertha Newcombe died on 11th June 1947 at Petersfield Hospital, aged 90. Her effects were valued at £15,473. 19s. 1d. (45) As Elizabeth Crawford pointed out: "Her social conscience made manifest in her will in which she requested that the proceeds of the sale of property she held in London should be invested in the Shoreditch Housing Association to be devoted to the housing in flats or rooms of elderly women of limited means. In addition she left the residue of her estate to the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings to be used for the preservation or repair of almshouses, preferably those suitable for women. She also had money invested in the Women's Pioneer Housing Association." (46)

Primary Sources

(1) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (9th October 1894)

When first I was married, I feared that my happiness would dull my energies and make me intellectually dependent. I no longer feel that; the old fervour for work has returned without the old restlessness… On the whole, then, I would advise the brain-working woman to marry – if only she can find her Sidney!

Beyond Shaw, Wallas and Bertha Newcombe and Rosy Williams we have seen few people here. Rosy and Noel Williams have stayed some three weeks. Rosy is like a shade from the old family life… She likes being with us; the three men make a pet of Noel and are kind to her, and she is not oppressed with our superiority in wealth and successfulness as with the other sisters.

(2) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (9th April 1895)

Sidney and I are both somewhat exhausted and we go tomorrow for a week to Beachy Head with a party of six – Graham Wallas and Bernard Shaw, Albert Ball (an old fellow traveller in the Tyrol), C. P. Trevelyan and Herbert Samuel (a wealthy young Jew with Fabian perspective), and, as the only other woman beside myself, Bertha Newcombe, the Fabian artist. What fortunate people we are: Love, Work, Friends and Health, given holidays whenever we need it! An Ideal Life!

(3) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (9th March 1897)

As I mounted the stairs with Shaws's Unsocial Socialist to return to Bertha Newcombe I felt somewhat uncomfortable as I knew I should encounter a sad soul full of bitterness and loneliness. I stepped into a small wainscoted studio and was greeted coldly by the little woman.

She is petite and dark, about forty years old, but looks more like a wizened girl, than a fully developed woman. Her jet-black hair, heavily fringed, half smart, half artistic clothes, pinched aquiline features and thin lips, give you a somewhat unpleasant impression though not wholly inartistic. She is bad style without being vulgar or common or loud – indeed many persons, Kate Courtney for instance, would call her "lady-like" – but she is insignificant and undistinguished. "I want to talk to you, Mrs Webb," she said when I seated myself. And then followed, told with the dignity of devoted feeling, the story of her relationship to Bernard Shaw, her five years of devoted love, his cold philandering, her hopes aroused by repeated advice to him (which he, it appears, had repeated much exaggerated) to marry her, and then her feeling of misery and resentment against me when she discovered that I was encouraging him "to marry Miss Townshend". Finally, he had written a month ago to break it off entirely: they were not to meet again. And I had to explain with perfect frankness that so long as there seemed a chance for her I had been willing to act as chaperone, that she had never been a personal friend of mine or Sidney's that I had regarded her only as Shaw's friend, and that as far as I was concerned I should have welcomed her as his wife. But directly I saw that he meant nothing I backed out of the affair. She took it all quietly, her little face seemed to shrink up and the colour of her skin looked as if it were reflecting the sad lavender of her dress.

"You are well out of it, Miss Newcombe," I said gently. "If you had married Shaw he would not have remained faithful to you. You know my opinion of him - as a friend and colleague, as a critic and literary worker, there are few men for whom I have so warm a liking; but in his relations with women he is vulgar, if not worse; it is a vulgarity that includes cruelty and springs from vanity".

As I uttered these words my eye caught her portrait of Shaw – full-length, with his red-gold hair and laughing blue eyes and his mouth slightly open as if scoffing at us both, a powerful picture in which the love of the woman had given genius to the artist. Her little face turned to follow my eyes and she also felt the expression of the man, the mockery at her deep-rooted affection. "It is so horribly lonely," she muttered. "I daresay it is more peaceful than being kept on the rack, but it is like the peace of death."

There seemed nothing more to be said. I rose and with a perfunctory "Come and see me – someday," I kissed her on the forehead and escaped down the stairs. And then I thought of that other woman with her loving easygoing nature and anarchic luxurious ways, her well-bred manners and well-made clothes, her leisure, wealth and knowledge of the world. Would she succeed in taming the philanderer?

(4) Joseph R. Orgel, Undying Passion (1985)

Some of his (George Bernard Shaw's) later affairs were protracted; he emerged battle-scarred from a five-year relationship with the beautiful red-haired and blue-eyed Fabian artist Bertha Newcombe.

(5) Janet Dunbar, Mrs. G.B.S: A biographical portrait of Charlotte Shaw (1963)

He (George Bernard Shaw) had been involved in two love affairs, one with the actress, Florence Farr, and the other with Bertha Newcombe, a portrait painter of uncommon talent and a vulnerability to romantic passion.

(6) Anthony Matthews Gibbs, Bernard Shaw: A Life (2006)

He was engaged in sexually consummated affairs with both Jenny Patterson and Florence Farr and had entered into numerous other relationships with women, characterized by varying degrees of intensity and romantic passion. In this period Bertha Newcombe, the artist who gave us the memorable visual image of Shaw as public speaker, became one in a long procession of Fabian women – like the troop of hapless, deserted wives who emerge as the gallows scene of the irresistible but faithless highwayman Captain Macheath at the end of John Gay's Beggar's Opera – who fell hopelessly in love with Shaw. An illusion to Bertha's succumbing to the charms of her subject is found in the sub caption added to the title "GBS Platform Spellbinder" in Sixteen Self-Sketches portrait by Bertha Newcombe. Far from running away from emotional entanglements in his career as a "platform spellbinder", Shaw entered into a new phase of philandering.

(7) Michael Holroyd, George Bernard Shaw - the Search for Love (1988)

Bertha Newcombe looked a good candidate (as a potential wife for George Bernard Shaw). That she was Fabian was essential; that she was 'lady-like' no disadvantage; and that she was 'not wholly inartistic' an unlooked-for bonus. She was in her thirties and, despite her aquiline features, thin lips and a figure that put Beatrice in mind of a wizened child, not perhaps lacking absolutely in all attraction. At least she was quite smartly turned out petite and dark, with neat, heavily fringed black hair. And she was devoted to Shaw.

(8) George Bernard Shaw, letter to Janet Achurch (24th August 1895)

Everybody seems bent on recommending me to marry Bertha - a fact fatal to her hopes (if it is fair to accuse her of hopes). The feeling, as I understand it, is that there is a fearful danger of my marrying somebody, and that it is perhaps more prudent to pair me with Bertha than to run the risk of my being borne off by someone worse. Now my own view is that since she is neither strong enough nor disorderly enough for a lawless life, nor cold & self-sufficient enough to enjoy a genuinely single one, she ought to marry someone else. She is only wasting her affections on me. I give her nothing; and I do not even take everything - in fact I don't take anything, which makes her most miserable. She has no idea with regard to me except that she would like to tie me like a pet dog to her easel & have me always make love to her when she is tired of painting. And she might just as well feel that way to Cleopatra's needle.

(9) Robert A. Gaines, Bernard Shaw's Marriages and Misalliances (2017)

In the middle 1880s, many of the young women in the new Fabian Society such as Grace Gilchrist and Grace Black found Shaw sexually attractive and were disappointed when he did not reciprocate. To Bertha Newcombe, who painted a notable portrait of him at the time, "GBS Platform Spellbinder (1896), he wrote, "Heavens! I had forgotten you – totally forgotten you You may play me as a trump card for all I am worth; but I cannot play myself… It was ever thus, Bertha. Your sex likes me as children like wedding cake, for the sake of the sugar on the top". To Janet Achurch he wrote, in 1895, "everybody seems best on recommending me to marry Bertha.

(10) Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited (2004)

Bertha Newcombe, an artist friend of the Hardys, visited them at Max Gate in March 1900 and reported in a letter to Nellie Gosse that she had felt much sympathy and pity for the way in which Emma was "struggling against her woes. She asserts herself as much as possible and is a great bore, but at the same time is so kind and goodhearted, and one cannot help realising what she must have been to her husband. She showed us a photograph of herself as a young girl, and it was very attractive." Emma also gave Miss Newcombe, as she had given Mabel Robinson, her own version of how she had first met the "ill-grown, under-sized young architect" in Cornwall, discarded his genius, and encouraged him to write "I don't wonder", Miss Newcombe continued, "that she resents being slighted by everyone, now that her ugly duckling has grown into such a charming swan. It is so silly of her though isn't it not to rejoice in the privilege of being wife to so great a man?

(11) Margot Peters, Bernard Shaw and the Actresses (1980)

Shaw had begun to sit for his portrait to a Chelsea artist named Bertha Newcombe at her studio at Cheyne Walk on 14 February 1892. As the portrait progressed so did, inevitably, did the painters fascination with the sitter. On 17 February Shaw gave her a sitting until nine-thirty in the evening and dined with her afterward – she could not let him go home.

(12) D. A. Hadfield, Shaw and Feminism: On Stage and Off (2016)

In a troubling letter he wrote to Bertha Newcombe in 1896, a painter who had hoped to marry him, he dismissively refers to "vivisection" as a cliched set piece of feminine hyperbole: "Your sex likes me as children like wedding cake, for the sake of the sugar on top. If they taste by accident a bit of crumb or citron, it is all over; I am a fiend, delighting in vivisectional cruelties, as indicated by the corners of my mouth." Shaw's devilish smile indicates his inhumane delight, his alleged attraction to cruelty in wooing and then abandoning lovers. But are might just as accurately locate his cruelty in the dismissive comparison of Newcombe to a selfish child, or the cavalier attitude Shaw adopts toward the otherwise serious topic of vivisection.

(13) Bertha Newcombe in a letter to Ashley Dukes in 1928. Included in Anthony Matthews Gibbs, Shaw: Interviews and Recollections (1990)

Shaw was, I should imagine, by preference a passionless man. He had passed through experiences and he seemed to have no wish for and even to fear passion though he admitted its power and pleasure. The sight of a woman deeply in love with him annoyed him. He was not in love with me, in the usual sense, or at any rate as he said only for a very short time, and he found I think those times the pleasantest when I was the appreciative listener. Unfortunately on my side there was a deep feeling most injudiciously displayed & from this distance I realise how exasperating it must have been to him. He had decided I think on a line of honourable conduct - honourable to his thinking. He kept strictly to the letter of it while allowing himself every opportunity of transgressing the spirit. Frequent talking, talking, talking of the pros & cons of marriage, even to my prospects of money or the want of it, his dislike of the sexual relation & so on, would create an atmosphere of love-making without any need for caresses or endearments.

Lovemaking would have been very delightful, doubtless, but I wanted, besides, a wider companionship and as I was inadequately equipped for that, except as a painter of some intelligence, he refused to give more than amusement."

(14) Michiko Kakutani, New York Times (27th September, 1981)

He was a socialist, for instance, who championed the suffragette movement, yet frequently employed the misogynist vocabulary of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche in his plays, describing woman as a predatory animal intent on imprisoning her male prey. He claimed that he had always ''stood up for the intellectual capacity of women,'' yet assigned the power of fecundity to ''mother woman,'' while reserving creativity for ''artist man.'' And in his own life, he disdained sexuality - he failed to consummate his own marriage - but cherished a high-flown romanticism, carrying on firey romances with some of the leading actresses of the day.

Influenced by Mill and Marx, Shaw also believed that the conventional bourgeoise family was an artificial institution designed to enforce the prevailing morality, while reducing women to chattel. ''Now of all the idealist abominations that make society pestiferous,'' he wrote in ''The Quintessence of Ibsenism'' in 1891, ''I doubt if there be any so mean as that of forcing self-sacrifice on a woman under the pretence that she likes it.. if we have come to think that the nursery and the kitchen are the natural sphere of a woman, we have done so exactly as English children come to think that a cage is the natural sphere of a parrot because they have never seen one anywhere else.''

Forceful as Shaw's rhetoric is, however, it would be a mistake to regard him as a simple, unabashed feminist. Both his plays and his own experiences, after all, reveal a curious distrust of women, stemming from his puritan suspicion of sex and romance. ''Women have never played an important part in my life,'' he told a friend once. ''I could always discard them more readily than my friends... women have been a ghastly nuisance.''

'"I was never duped by sex as a basis for permanent relations, nor dreamt of marriage in connection with it," he wrote Frank Harris. "I put everything else before it, and never refused or broke an engagement to speak on Socialism to pass a gallant evening. I valued sexual experience because of its power of producing a celestial flood of emotion and exaltation which, however momentary, gave me a sample of the ecstasy that may one day be the normal condition of conscious intellectual activity."

Passionate, tempestuous and fiercely possessive, Jenny Patterson soon became a burden, and when Shaw spurned her in favor of Florence Farr, a series of terrible scenes ensued. Mrs. Patterson would become the model for Blanche Sartorius in '"Widowers' Houses'" - a role which, ironically enough, would be played on stage by Miss Farr - as well as Julia in '"The Philanderer," a play in which ''a famous Ibsenite philosopher'' much like Shaw himself is chased, relentlessly, by women...

Certainly Jenny Patterson was not the only woman to set her sights on Shaw. There was also Edith Bland - the wife of Hubert Bland, a founder of the Fabian Society - who followed him to his favorite haunts in London; and there was Annie Besant, the solemn Freethinker and orator, who presented Shaw with a formal contract, detailing the terms on which she would be willing to live with him, despite her marriage to another man.

(15) BBC News, 'Lost' George Bernard Shaw painting given to Labour Party (22nd June 2012)

A painting of the playwright George Bernard Shaw, which was found at an Oxford college, is to be handed back to its original owner, the Labour Party.

The artwork was identified by Professor Audrey Mullender, principal of Ruskin College.

She said: "I did some research and became quite excited when it appeared that it might be this lost portrait."

Andrew Smith, Labour MP for Oxford East, said it would be hung in Labour's new headquarters in Westminster.

The portrait, known as GBS - The Platform Spellbinder, was painted in 1892 before Shaw was known as a writer.

It is 5ft (1.5 m) high and 3ft 2in (0.9 m) wide and is estimated to be worth between £10,000 and £20,000.

Shaw was involved romantically with its painter, Bertha Newcombe.

Until its rediscovery the painting was thought to have been lost during World War II.

It is not known why it was moved to Oxford from the Labour Party headquarters in London.

Prof Mullender added: "I noticed this painting, which has been hanging high up on a wall in a common room for many years.

"A timely visit from Canada by the President of the International Shaw Society, who knew of a reproduction of the painting in one of Shaw's own books, confirmed that I had, indeed, found the missing work."

The professor will officially hand over the portrait to Mr Smith on Friday.

Mr Smith said: "It is amazing that such a big picture got lost, but greatly to the credit of Ruskin College that they have found it, together with the note on the back which confirmed it as the property of the Labour Party.

"I'm sure everyone will be happy that George Bernard Shaw, one of the leading lights in the early years of the party, will be coming home."

Shaw was less than complimentary about Ruskin College when it was founded in 1899.

He refused to be associated with Ruskin Hall, as it was then called, claiming the enterprise of turning "workmen into schoolmen" would fail as an enterprise.

Prof Mullender said: "Ruskin College is still here in Oxford, over a century later, and we are still changing lives - only these days they call it 'social mobility' and everyone wants to learn from us how to do it."

Shaw, who wrote scores of plays, including Pygmalion, died in 1950.

(16) David Simkin, Family History Research (24th September, 2023)

Bertha Newcombe was born at Priory House, Lower Clapton, London on 17th February 1857 to Hannah Hales Anderton and Samuel Prout Newcombe, a schoolmaster who ran a school at Priory House and owned a chain of photographic portrait studios trading under the name of The London School of Photography. Bertha had a brother Claude Newcombe (1859–1925) who apparently emigrated to Australia, where he died in 1925, and a half brother Frederick Samuel Newcombe (born 1850), a son from her father's first marriage. Bertha's sisters were Ada Mary Newcombe (1854–1924), Mabel Newcombe (1862-1947), Jessie Winifred Newcombe (1864–1943) - the only one who married - and a half-sister Mary White Newcombe (born 1851), a child from her father's first marriage.

When Samuel Prout Newcombe married his first wife Mary Harriet White on 28th June 1849 in Islington, North London,, he is recorded on the marriage register as a "Schoolmaster".

On the 1851 Census, Samuel Prout Newcombe is described as a 27-year-old "Schoolmaster & Author". Samuel P. Newcombe's first wife, Mrs Mary Harriet Newcombe, died in 1853.

When Samuel Prout Newcombe married Hannah Hales Anderton on 22nd December 1854, he gave his rank or profession as "Gentleman",

At the time of the 1861 Census, 4-year-old Bertha was living with her parents and siblings at an address in Dorking, Surrey. On the 1861 census return, Bertha's father, Samuel Prout Newcombe, is described as a 37-year-old "Watercolour Painter". When the 1871 Census was taken the Newcombe family were residing at 'Northcote', Park Hill Road, Croydon, Surrey. Her father, Samuel Prout Newcombe, was now describing himself as a "Retired Solicitor".

At the time of the 1881 Census,Bertha Newcombe was visiting friends in Camberwell, Surrey. The census enumerator records Bertha as a 24-year-old "Artist". In 1881, Bertha's father, mother and two younger sisters, Mabel and Jessie, were boarding at a lodging house in Hastings, Sussex. On the 1881 Census return, Samuel Prout Newcombe declared that he had an "Income from Mortgages & Dividends".

From around 1894, the Newcombe's main residence was at No.1 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, S. W. London. The 1901 census records Samuel Prout Newcombe, his wife Hannah and their three unmarried daughters at No.1 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. Sharing Samuel Newcombe's Chelsea home were forty-four year old Bertha Newcombe and her two younger sisters Mabel Newcombe, aged 38, and thirty-six year old Jessie Winifred Newcombe. The Head of the Household at No.1 Cheyne Walk was Bertha's seventy-seven year old father Samuel P. Newcombe, described as living on his "Own Means".

The 1911 Census records Bertha and Mabel residing with her widowed father at No.1 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. Samuel Newcombe and his two unmarried daughters were living on "Private Means" and employed 4 domestic servants at their Chelsea home. Bertha Newcombe worked from "a small wainscoted studio" at her father's house in Chelsea until Samuel Prout Newcombe's death in 1912. Bertha Newcombe spent the last years of her life at Redlynch (Red Lynch), Tilmore, Petersfield, Hampshire.

When the 1921 Census was taken, 64-year-old Bertha Newcombe was boarding at a large hotel at 7-9 Victoria Road, Kensington, London, W8. No occupation is given for Miss Bertha Newcombe.

When the General Register of 1939 was compiled, Bertha Newcombe was living with her younger sister Mabel Newcombe at 'Redlynch' Tilmore, Petersfield, Hampshire.

Bertha Newcombe of Redlynch, Tilmore, Petersfield, Hampshire, spinster, died on 11th June 1947 at The Hospital, Petersfield, aged 90. Her effects were valued at £15,473. 19s. 1d.

Her younger sister, Mabel Newcombe, who lived with Bertha at 'Redlynch' in Petersfield in their declining years, died 3 months later on 12th September 1947 at Elvington Nursing Home in Midhurst, Sussex.