Emily Duval

Jane Emily Hayes, the daughter of Jane and Thomas Hayes, a "Coachman" in domestic service, was born in the Mayfair district of London on 25th November 1860.

On 19th September 1881, Emily Hayes married Ernest Duval at St Mary's Church, Battersea. Jane gave birth to nine children: Ernest (1882), Victor (1885), Walter (1887), Barbara (1888), Norah (1891), Elsie (1893), Winifred (1895), Gurney (1897) and Ivy (1901). The family lived at 52 Wycliffe Road, Battersea. (1)

Emily Duval was a supporter of women's suffrage and she joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) in 1906. At a conference in September 1907, Emmeline Pankhurst "tore up the constitution" and told members that she intended to run the WSPU without interference. (2)

As Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence pointed out: "She called upon those who had faith in her leadership to follow her, and to devote themselves to the sole end of winning the vote. This announcement was met with a dignified protest from Mrs. Despard. These two notable women presented a great contrast, the one aflame with a single idea that had taken complete possession of her, the other upheld by a principle that had actuated a long life spent in the service of the people. Mrs. Despard calmly affirmed her belief in democratic equality and was convinced that it must be maintained at all costs. Mrs. Pankhurst claimed that there was only one meaning to democracy, and that was equal citizenship in a State, which could only be attained by inspired leadership. She challenged all who did not accept the leadership of herself and her daughter to resign from the Union that she had founded, and to form an organisation of their own." (3)

and Norah sitting in the front. (c. 1904)

Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst sent out a letter to all branches of the WSPU stating that this was not in any way a democratic group. "We are not playing experiments with representative government. We are not a school for teaching women how to use the vote. We are a militant movement... It is not a school for teaching women how to use the vote. We are militant movement... It is after all a voluntary militant movement: those who cannot follow the general must drop out of the ranks." As Simon Webb has pointed out: "This is quite unambiguous. Members must not expect to influence policy or question the leader, the role is limited to obeying orders." (4)

Women's Freedom League

As a result of this speech, Emily Duval, Muriel Matters, Helen Fox, Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, Edith How-Martyn, Violet Tillard, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Octavia Lewin, Emma Sproson, Margaret Nevinson, Henria Williams and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Most of its members were socialists who wanted to work closely with the Labour Party who "regarded it as hypocritical for a movement for women's democracy to deny democracy to its own members." (5)

In 1907, Emily Duval joined the National Executive Committee of the Women's Freedom League and became chair of the Battersea branch. Three of her daughters, Barbara, Norah and Elsie, also joined the WFL. (6) Margaret Nevinson often appeared with Emily Duval making speeches in favour of women's suffrage. "Many of us remember with an ache of the throat even to this day how many rowdy meetings we addressed in South London parks and street corners, and the personal violence with which our gospel was received, but she, as organiser, never failed, not faltered, nor wearied in well-doing." (7)

In January 1908 Emily was sentenced to one month's imprisonment after taking part in a deputation to H. H. Asquith, the prime minister, at his home at Cavendish Square. (8) Later that year Emily Duval was in trouble with the courts again: "The Suffragettes have started on a new campaign, that of publicly protesting against the trial of voteless women by man-made laws. In all the London courts suffragettes appeared, and made their protests, being removed in all cases without force. Mrs Emily Duval championing a woman charged with disorder and obscene language. 'Take her out,' said Mr Plowden; 'I cannot have this disturbance.' She went quietly." (9)

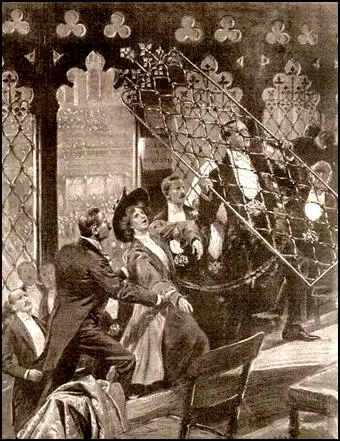

On 28th October 1908 Muriel Matters organised a Women's Freedom League demonstration that would gain the maximum publicity. Matters and Helen Fox were in the ladies' gallery of the House of Commons, then enclosed from the rest of the chamber by a metal grille. The two women interrupted the business of the house by demonstrating for women's suffrage. "While attached to the grille Matters, by a legal technicality, was judged to be on the floor of Parliament and thus, the words spoken by her that day are still considered to be the first delivered by a woman in the House of Commons." (10)

When officials made attempts to remove them, it was discovered that they had chained and padlocked themselves to the grille in such a way that in order to remove them the grille would have to be removed as well. The two women sat in a committee room until a locksmith was found to separate them from the thirty-foot long grille. (11)

Muriel Matters then went round to join the demonstration taking place in front of Parliament. Fifteen arrests were made including Emily Duval, Muriel Matters, Violet Tillard, Alison Neilans, Barbara Duval, Arnold Cutler, Edith Bremer, Margaret Henderson and Marion Leighfield. (12)

Emily and Barbara Duval were charged with disorderly conduct. Emily paid her fine and Barbara was released after promising to refrain from further militancy until she was twenty-one. At her trial, Emily was described as "a lady agitator who was bringing up her daughter to be a lady agitator". (13)

In February 1909, Emily Duval was sentenced to six weeks imprisonment in Holloway Prison. In prison she met and befriended Constance Lytton. (14) According to Diane Atkinson, the Rise Up, Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (2018) she spent almost all the time in the hospital wing suffering from acute neuritis. (15)

Victor Duval

Emily Duval had also brought up her son Victor Duval to be involved in politics. He was secretary of the Clapham League of Young Liberals but resigned in 1909 after seeing women's suffrage protestors being badly treated at a meeting where John Burns, a government cabinet minister, was speaking. (16) Duval was "severely handled many times when protesting at Cabinet Ministers’ meetings." (17)

In the summer of 1909 Duval was charged with "aiding and abetting" Marion Wallace-Dunlop in stencilling an advertisement for the suffragettes' Bill of Rights procession on the walls of St Stephen's Hall. (18) The Wandsworth Borough News reported: Marion Wallace Dunlop, 44, described as an artist, on Montpelier Road, Ealing, was charged with wilfully damaging the stonework of St Stephen's Hall, House of Commons, by stamping it with an indelible rubber stamp; and Victor Duval, 25, clerk, of Lindor Road, Battersea, was accused of aiding and abetting her. Duval said he wished to complain about having been locked up in an insanitary cell for four hours and a half before he was bailed out." (19)

On 13th January 1910, Victor Duval, formed the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement (MPU). Duval later explained that "The society was formed as a result of a growing conviction among men, as well as women, that the delay in removal of the sex disqualification from the Parliamentary franchise was due to the determined indifference of the Government rather than to any considerable opposition in the country." (20)

In a leaflet published in 1910 the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement pointed out that it would oppose all governments in power until such time as the franchise is granted. The MPU outlined the methods it would use: "Vigorous agitation and the education of public opinion by all the usual methods, such as public meetings, demonstrations, debates, distribution of literature, newspaper correspondence and deputations to public representatives." (21)

On 17th October, 1910, Victor Duval was charged with using threatening and insuting language when David Lloyd George arrived at the City Temple to address a meeting of the Liberal Christian League. The police alleged that Duval had rushed from the crowd, and grabbed the chancellor's coat lapels as he got out of his motor car, shouting, "Traitor! Lloyd George, you're a scoundrel, and a traitor to the woman's cause." Duval was found guilty and was sentenced to seven days in Pentonville Prison. (22)

In November 1911 Victor Duval was arrested during a demonstration outside the House of Commons. "The defendant, Victor Duval had been remanded last week that he might call evidence for the defence on a charge of obstruction. One witness said the policeman clutched Duval's throat, and forced his head back for two or three minutes. The police behaved riotously towards the woman in his opinion. Prisoner also made allegations against the police. After fining Duval 10s on a charge of obstruction the Magistrate said there had been a good many cases arising out of the disturbances, and he had dealt leniently with them. If anything of the kind occurred again the offenders must not expect to get off so easily. In cases of wilful damage, especially of personal violence, he should deal very differently with offenders than he had on this occasion." (23)

On the 20th December 1911 the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement held a special dinner in honour of the entire Duval family. The main speaker was the veteran women's suffrage campaigner, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. (24)

Women's Social and Political Union

In November 1911 Emily Duval left the Women's Freedom League because she did not feel it was militant enough and rejoined the Women Social & Political Union. (25) The following year she was sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment for window smashing. At her trial Emily commented: "It's no use saying much in this court of injustice. I am prepared to die for our cause." (26) On 26th March, 1912 she received a six months sentence, which was spent in Winson Green Prison. Emily joined the hunger-strike that was taking place and was force-fed, and in July was released and taken to a nursing home. (27)

In 1911 Victor Duval met Una Dugdale, an active member of the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). Dugdale had earlier explained why she was a militant suffragette: The Uxbridge Gazette reported: "The militant tactics had not put back the movement, but on the contrary had put more life and new blood into it. She falsified the statements that the methods of the suffragettes in the past were unwomanly, and said that self-presentation applied to women as well as men. Women's honour and their birth right was at present behind locked doors, and it behoved them to force the doors down. They had to walk side of the whole of their sex, not only of these islands, but all over the world." (28)

The couple married on 13th January 1912. It was announced that the word "obey" would be omitted from the marriage service at the Savoy Chapel. However, the Archbishop of Canterbury, sent his representative to tell the Rev. Hugh Chapman, that the omission would make the validity of the marriage doubtful. "The couple acquiesced, and the usual marriage ceremony was proceeded with." (29)

with bridesmaids and pageboy (13th January, 1912)

Margaret Nevinson later pointed out in The Vote, the newspaper of the Women's Freedom League, that the wedding had "the unique experience of a ceremony where bride and bridegroom, bridegroom's mother, most of the bridesmaids, and many of the guests had all suffered terms of imprisonment." (30)

In the Pall Mall Gazette, the vicar who officiated at her wedding, Hugh Chapman, argued that there should be a discussion on the wording of the wedding service. "The intention of a true marriage is that the service entered on should be altogether mutual and equal, each glorying in a deference which crowns the other without the smallest lowering of themselves. It would most assuredly be a good work and is clear case for a referendum to the clergy, if their opinions on the whole subject were canvassed throughout." (31)

It was reported in the Aberdeen Press and Journal that the story had begun a national debate on the subject. Millicent Leveson-Gower, Duchess of Sutherland, stated that "obey" an unnecessary word. "Love and honour" stand much stronger without it. Jennie Spencer-Churchill, the wife of George Cornwallis-West said that although the "husband should be recognised as the head of the house between two people who are admittedly to the companions, the word is grotesque." The newspaper quoted Lena Ashwell and Beatrice Harraden as saying they would have the word "obey" left out of the wedding service. (32)

As Catherine Blackford pointed out: "Marriage reform had long been a feminist concern and Duval's standpoint signified a feminist commitment to marriage as an equal partnership based on love and respect rather than subservience and subordination." (33) Later that year she explained her reasons for departing from convention in her pamphlet Love and Honour but not Obey. (34)

Elsie Duval

Several of her children were involved in the women's suffrage movement. Barbara Duval and Nora Duval were arrested and imprisoned for window breaking in 1911 and 1912. Norah also helped Lilian Lenton to escape police surveillance during her arson campaign. (35)

The most militant was Elsie Duval who joined the Women Social & Political Union at the age of fifteen. In January 1908 Elsie Duval was sentenced to one month's imprisonment after taking part in a demonstration at the home of Herbert Asquith. (36)

Duval also took part in the WSPU's arson campaign. It is believed she was responsible for burning Sanderstead Station. She was arrested for "loitering with intent" on 3rd April 1913. She was sentenced to one month's imprisonment. After being released under the Cat and Mouse Act, she escaped with her boyfriend, Hugh Franklin, to Belgium and stayed in Brussels. She received a letter from Jessie Kenney that said: "Miss Pankhurst thinks it would be better for you to stay where you are for the time being and until you get stronger." (37)

East London Federation of Suffragettes

Sylvia Pankhurst grew increasingly unhappy about the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) decision to abandon its earlier commitment to socialism. She also rejected the WSPU attempts to gain middle class support by arguing in favour of a limited franchise. Pankhurst made the final break with the WSPU when the movement adopted a policy of widespread arson. Sylvia now concentrated her efforts on helping the Labour Party build up its support in London. (38)

Emily Duval agreed with Sylvia Pankhurst and with the help of Keir Hardie, Norah Smyth, Zelie Emerson, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Maud Joachim, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury they established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. Pankhurst also began production of a weekly paper for working-class women called The Women's Dreadnought. (39)

Emily Duval was arrested again on 22nd May 1914, along with Sarah Carwin and her son Victor Duval. "Following on the Suffragette disturbances at Bow Street Police Court yesterday, five defendants appeared before Sir John Dickinson, today. Sarah Carwin kept up a running commentary during the evidence. She was ordered to be bound over, and left the dock protesting against the course... Mrs Emily Duval, who was charged with assault and disorderly conduct, said she went to her son's assistance when she saw him struck. A police-sergeant stated that the defendant struck him in the face and kicked him. Mr Musket, for the police, said the accused had also previous convictions against her. She was now fined 40s or 20 days. A fine of £3 was made on her son, Victor Duval, charge with striking a detective constable and with disorderly conduct." (40)

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort, but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (41)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (42)

Victor Duval of the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement shouted out "Votes for Women". Christabel rebuked him by commenting "We cannot discuss that now." (43) Sylvia listened with dismay of her sister's speech, "wholly for the War; light, dialectic, as though of some academic political contest; no hint appeared of the appalling tragedy. I listened to her with grief, resolved to speak more urgently for peace." (44) Emily Duval agreed with her son and condemned the decision of the WSPU to support the First World War. (45)

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!". (46)

Later Life

After the war Emily Duval lost three of her daughters to the influenza epidemic. Winifred Duval (25th April 1918); Elsie Duval Franklin (1st January, 1919) and Barbara Duval Barry (5th January, 1919). (47)

Emily Duval continued to be involved in politics and after joining the Labour Party served on the Battersea Borough Council from 1918 to 1921. (48) Her political career came to an end "when she was stricken with paralysis, bearing her sufferings with characteristic courage and patience till the end. No doubt the strain of suffrage work, the war, and the tragic deaths of her three of her young daughters broke her down prematurely." (49)

Emily Duval died on 31st October 1924 at 37 Park Road, St John's Hill, Battersea, London. (50) The Vote reported that at her funeral: "The banner of the Women's Freedom League covered her coffin, and yellow and white chrysanthemums were conspicuous in the many wreaths brought by friends and old comrades." (51)

Primary Sources

(1) The Irish Independent (25th November 1907)

The Suffragettes have started on a new campaign, that of publicly protesting against the trial of voteless women by man-made laws. In all the London courts suffragettes appeared, and made their protests, being removed in all cases without force….

Mrs Emily Duval championing a woman charged with disorder and obscene language. "Take her out," said Mr Plowden; "I cannot have this disturbance." She went quietly.

(2) Exmouth Journal (31 October 1908)

Suffragettes cause of another scene in the House of Commons on Wednesday evenings. Two women chained themselves to the grille in front of the Ladies' Gallery, and a portion of the grille had to be removed by the police in order to release them…

Disturbances also occurred at the same time outside the House, leading to numerous arrests for disorderly conduct outside St. Stephen's Hall, and for attempting to harangue a throng at the base of the monument in front of the House of Lords. The two women who were the principal figures in the disturbances in the Ladies Gallery gave their names of Helen Fox and Muriel Matters…

No less than fifteen arrests were made in connection with the disturbances in St Stephen's Hall. They gave their names as follows: Arnold Cutler, Miss Violet Tillard, Miss Edith Bremer, Mrs. Emily Duval, Miss Margaret Henderson, Miss Alison Neilans, Miss Marion Leighfield… They were taken to Cannon Row Police Station, and were bailed out later.

(3) The Yorkshire Post (8th March 1912)

There was an almost monotonous reiteration and formality about the proceedings at Bow Street yesterday, when Mr. Curtis Bennett resumed the hearing of charges arising out of last Friday's organised window smashing. The prisoners entered the dock, evidence was given of their work of destruction, and they then passed back to the cells under sentences which varied only slightly, according to the degree of damage done. Mrs Emily Duval, on being committed for trial, exclaimed: "It's no use saying much in this court of injustice. I am prepared to die for our cause."

(4) The Suffragette (15th August 1913)

A meeting was held in Battersea Park on Sunday, August 3; speakers Mrs Mason and Mrs Duval. A sympathiser, a stranger gave 2s. 6d. for ten copies of The Suffragette, all that was left to be distributed among the crowd. Mrs Tyson and Mr E. Duval addressed a big meeting at Strath Terrace. The Suffragette sold out, and stock had to be bought from local newsagent. More parcels needed for jumble sale after summer vacation. Hon Secretary: Mrs Emily Duval, 37 Park Road, Wandsworth.

(5) Dublin Evening Herald (23rd May 1914)

Following on the Suffragette disturbances at Bow Street Police Court yesterday, five defendants appeared before Sir John Dickinson, today.

Sarah Carwin kept up a running commentary during the evidence. She was ordered to be bound over, and left the dock protesting against the course.

Another woman, described as "Number Four," aged 31, entering the dock, turned her back on the bench and clung to the rear rail of the dock. Her hands were pulled away. She then sat quietly and left the court in the ordinary manner. The charge against her was one of the insulting behaviour in throwing bags of flour at the magistrates, and, she was fined 40s or ten days.

Mrs Emily Duval, who was charged with assault and disorderly conduct, said she went to her son's assistance when she saw him struck. A police-sergeant stated that the defendant struck him in the face and kicked him.

Mr Musket, for the police, said the accused had also previous convictions against her. She was now fined 40s or 20 days.

A fine of £3 was made on her son, Victor Duval, charge with striking a detective constable and with disorderly conduct.

(6) The Daily Herald (21st June 1921)

The borough council by-election in the Winstanley ward (Battersea) resulted in a Labour win, the figures being: Duval (Labour) 846; Early (Anti-Waste) 240; Hanlon (Unemployed) 176.

(7) Margaret Nevinson, The Vote (14th November 1924)

On Wednesday last, in the peaceful cemetery of Merton, Surrey, our comrade Mrs Emily Duval was laid to her well-earned rest. Older members of the Women's Freedom League will remember that she was one of those who broke away from the Woman's Social and Political Union at the great schism in September, 1907, when the new League was formed on a question of principle and democratic control. Mrs Duval was elected one of the early members of the National Executive Committee, and was an enthusiastic and tireless worker for the cause.

Many of us remember with an ache of the throat even to this day how many rowdy meetings we addressed in South London parks and street corners, and the personal violence with which our gospel was received, but she, as organiser, never failed, not faltered, nor wearied in well-doing.

Mrs Dural was arrested with Miss Muriel Matters in connection with the celebrated Grille Protest on October 28 th , 1908, and together with fourteen others was sentenced to a fine of £5, or one month in the third division. It was on this occasion that the Young Turks, their hands still bloody from their fight for constitutional rights, arrived in England, and were feted by the Liberal Party. And whilst the woman lay in Holloway gaol – third class, with the hardened offenders – Mr Asquith had a lyrical burst in praise of freedom at the Guidlall Banquet, and congratulated the Young Turks on being "here tonight in the very centre and citadel of the Capital of Liberty, and we may claim the privilege of the oldest of the free countries of the world to greet with special satisfaction the birth of new institutions."

Later, February 13th , 1909, Mrs Duval was again arrested for doing absolutely nothing and received six weeks, second division, on the charge of "creating an obstruction," in spite of the fact that one witness (not arrested), being known to some of the newspaper men, admitted she herself had created such an obstruction of the reporters on the refuge outside, that the traffic in Whitehall went on the offside for ten minutes or more; however, being men, the obstruction counted for nothing. Mrs Duval's son and four daughters also went to gaol, and later, Mrs Duval joined in the window-smashing campaign of the Women's Social and Political Union, received a long sentence and went through the horrors of the hunger-strike and forcible feeding.

At the wedding of Mr Victor Duval to Miss Una Dugdale, in 1912, Hyde Park had the unique experience of a ceremony where bride and bridegroom, bridegroom's mother, most of the bridesmaids, and many of the guests had all suffered terms of imprisonment.

Mrs Duval was a member of the Battersea Borough Council from 1918 to 1921, when she was stricken with paralysis, bearing her sufferings with characteristic courage and patience till the end. No doubt the strain of suffrage work, the war, and the tragic deaths of her three of her young daughters broke her down prematurely. The banner of the Women's Freedom League covered her coffin, and yellow and white chrysanthemums were conspicuous in the many wreaths brought by friends and old comrades.

(8) David Simkin, Family History Research (24th March, 2023)

Victor Diederichs Duval was the second eldest son of Jane Emily Hayes (1860–1924) and Ernest Charles Augustus Diederichs Duval (1858–1953). Victor's father was born Ernest Charles Augustus Diederichs on 13th September 1858 in Mainz, in the Rhineland-Palatinate of Germany to an unmarried woman Emilie/Amelie Diederichs (born 1838, Alsace, France). As a baby, Ernest Diederichs was fostered out to a midwife and her husband, both Roman Catholics..Emilie's brother, Ernst Karl Diederichs, took financial responsibility for her son Ernest and served as his godfather. Ernest Charles Diederichs was baptised as a Protestant. (Ernest's putative father, Eduard Ludwig Schott von Schottenstein was a Lutheran Protestant).

By 1871, Ernest's mother, Emilie/Amelie Diederichs, was residing in London and was employed as a teacher. (At the time of the 1871 Census, Emilie / Amelie Diederichs was recorded as a "Professor of Music and German" and in the 1881 Census she was described as a "Teacher of French"). Between 1858 and 1875, Ernest Diederichs was brought up by his foster parents in Germany. Ernest Diederichs' foster father died in 1873 and his foster mother died in 1874. In 1875, with both his foster parents dead, Ernest Diederichs joined his mother in Battersea, London, but changed his surname to "Duval" so that his unmarried mother was not disgraced and could continue working as a teacher. On the 1881 Census return, Amelie Diederichs and her son Ernest are recorded at 52 Wycliffe Road, Battersea, London. Amelie Diederichs is described as an unmarried "Teacher of French" and her 23-year-old son (under the assumed name of 'Ernest Duval' ) is entered as her "lodger". Ernest Duval gives his occupation as "Correspondence Clerk". Living on the same road as Ernest Duval, at No. 37 Wycliffe Road, Battersea, is 20-year-old "Machinist" Jane Emily Hayes, the daughter of Jane and Thomas Hayes, a "Coachman" in domestic service. Jane Emily Hayes had been born in the Mayfair district of London on 25th November 1860.

On 19th September 1881, at St Mary's Church, Battersea, 23-year-old "Ernest Duval" married 20-year-old Jane Emily Hayes. On the marriage register "Ernest Duval" declared that his father was "Edward Duval, Merchant". Ernest Duval gives his occupation as "Correspondent". Amelie Diederichs (Ernest's mother) is recorded as a witness to the marriage.

The union of 'Ernest Duval' and Jane Emily Hayes produced 9 children:

(1) Ernest Edward Diederichs Duval (1882-1904) who worked as a "Commercial Clerk" before he died from heart disease at the age of 22.

(2) Victor Diederichs Duval (born 16th March 1885, Battersea, Surrey - died 4th October 1945, Queen Victoria Hospital, Morecambe, Lancashire) - see below.

(3) Walter Diederichs Duval (1887-1887). Died 10 days after birth from "Congenital malformation of heart".

(4) Barbara Diederichs Duval (born 11th September 1888, Battersea, Surrey - died 5th January 1919 at South London Hospital for Women, Clapham Common, London).

From the age of 20, Barbara Duval was active in the Women's Suffrage Movement.

1908. Arrested when Muriel Matters chained herself to the grille in the House of Commons. Released on promise to refrain from militancy until age of 21.

1911. Mass window-breaking, and rushing of police cordons. Siblings Elsie Duval and Victor Duval, and her mother, Mrs Jane Emily, also participated.

28 November 1911. Tried for militant suffragist activity at Bow Street Court.

1915. Married Denis Gerald Barry (born circa 1893, Bray, Dublin, Ireland). Served in the British Army during WW1. After the death of his wife, in 1921 emigrated to West Africa.

Marriage produced one child - Denis Francis Doyne Barry (1915–1988).

Death

On 5th January 1919, Barbara Barry (née Duval) died at South London Hospital for Women, Clapham Common, London. Cause of death: Influenza & Lobar Pneumonia. (Spanish 'Flu Epidemic?)(5) Norah Diederichs Duval (born 8th January 1891, Battersea, Surrey, – died 1972, Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire).

1912. Arrested for window smashing. 2nd March 1912, tried for window smashing at Bow Street Court, London. 4 months imprisonment.

20th June 1913. Assisted Lilian Lenton to escape police surveillance. Norah posed as a baker's boy, then changed clothes with Lilian who departed in the van.

16th July 1920 at St John the Evangelist Church, Putney, Norah Duval married Arthur Gerald Benstead (1889–1968), an electrical engineer.

Two sons from marriage - Derek Gerald Benstead (1922–1991) and Arthur Rodney Benstead (born 1926, Kingston, Surrey).6) Elsie Diederichs Duval (born 19th February 1893, Battersea, Surrey - died 1st January 1919, 35 Porchester Terrace, Hyde Park, London)

(7) Winifred Diederichs Duval (born 2nd June 1895, Battersea, Surrey - died 25th April 1918, Ewell Colony, Epsom, Surrey). Cause of death: "Pulmonary Tuberculosis".

(8) Gurney Diederichs Duval (born 27th November 1897, Battersea, Surrey - died some time after 1967). Served in the British Army during WW1. Worked in various jobs - electrical engineer, cafe owner, security officer. Married twice. First marriage dissolved.

(9) Ivy Emily Diederichs Duval (1901–1902). Died in infancy.