Louisa Thomson-Price

Louisa Catherine Sowdon was born on 18th April 1864. Her father, William Henry Sowdon married her mother, Matilda Hutton Sowdon, aged 19, at St Saviour's Church, Jersey, on the 8th November, 1860. (1) Louisa later recalled that her father was "a captain in the 2nd Life Guards (Blue) and belonging to a family whose records were unbrokenly orthodox and Tory". (2)

It was not a happy marriage. Matilda recalled "Shortly after our marriage my husband began to give way to intoxication, and after a time he used very bad language to me; his conduct soon became worse; he frequently stayed away from home for several days together – often remained out late at night, and sometimes all night. On one occasion he remained away a whole week." (3) According to one report shortly before Louisa was born Sowdon "wilfully infected her (Matilda) with venereal disease". (4)

In 1870 Matilda Sowden remarried and had another five children with her second husband, Thomas Caudwell, a commercial traveller. Louisa was an early advocate of women's suffrage and took a keen interest in the proposal to give the vote to women in 1884. A total of 79 Liberal Party MPs urged William Gladstone to recognize the claim of women's householders to the vote. Gladstone replied that if votes for women was included Parliament would reject the proposed bill: "The question with what subjects... we can afford to deal in and by the Franchise Bill is a question in regard to which the undivided responsibility rests with the Government, and cannot be devolved by them upon any section, however respected , of the House of Commons. They have introduced into the Bill as much as, in their opinion, it can safely carry." (5)

The bill was passed by the Commons but was rejected by the Conservative dominated House of Lords. Gladstone refused to accept defeat and reintroduced the measure. This time the Conservative members of the Lords agreed to pass Gladstone's proposals in return for the promise that it would be followed by a Redistribution Bill. Gladstone accepted their terms and the 1884 Reform Act was allowed to become law. This measure gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughs - adult male householders and £10 lodgers - and added about six million to the total number who could vote in parliamentary elections. (6)

However, this legislation meant that all women and 40% of adult men were still without the vote. According to Lisa Tickner: "The Act allowed seven franchise qualifications, of which the most important was that of being a male householder with twelve months' continuous residence at one address... About seven million men were enfranchised under this heading, and a further million by virtue of one of the other six types of qualification. This eight million - weighted towards the middle classes but with a substantial proportion of working-class voters - represented about 60 per cent of adult males. But of the remainder only a third were excluded from the register of legal provision; the others were left off because of the complexity of the registration system or because they were temporarily unable to fulfil the residency qualifications... Of greater concern to Liberal and Labour reformers... was the issue of plural voting (half a million men had two or more votes) and the question of constituency boundaries." (7)

Louisa was furious with William Gladstone for not giving women the vote and suggested that many people with radical views left the Liberal Party. "There had been a slump in constitutional methods since Gladstone betrayed the Liberal women in 1884, when in the Bill to extend the franchise he refused to accept the amendment to include women as voters on the same terms as men. He declared that it would 'sink the ship', and to avoid any catastrophe to himself he threw the women overboard." (8)

Louisa was a talented cartoonist and in 1886, aged 22, she published a book, Comic Sketches and Sober Thoughts. (9) Louisa also developed radical political views and was sympathetic to the Social Democratic Federation and attended the meeting that took place on 13th February, 1887 in Trafalgar Square to protest against the policies of the Conservative Government headed by the Marquess of Salisbury. The police broke up the meeting and John Burns and Robert Cunninghame Graham were put on trial for their involvement in the demonstration that became known as Bloody Sunday. (10)

Louisa later recalled: "And when John Burns came out of the prison to which he had been sentenced as a result of claiming the right of free speech in Trafalgar Square, I was one of those who assembled to welcome him. It is strange to think that the John Burns of today, who would deny us free speech, was the same man who desired it sufficiently for the working men of England that he was not afraid to suffer for it." (11)

National Secular Society

As a young woman Louisa became an admirer of Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant. The were members of the National Secular Society (NSS). In 1877 Bradlaugh and Beasant published The Fruits of Philosophy, written by Charles Knowlton, a book that advocated birth control. Besant and Bradlaugh were charged with publishing material that was "likely to deprave or corrupt those whose minds are open to immoral influences". In court they argued that "we think it more moral to prevent conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air and clothing." Besant and Bradlaugh were both found guilty of publishing an "obscene libel" and sentenced to six months in prison. At the Court of Appeal the sentence was quashed. (12)

Louisa later recalled: "Charles Bradlaugh I have always had the most profound admiration. When he was President of the National Secular Society I was one of its members, and spoke for that body many times. Misunderstood and maligned as he was, he was a man of magnificent courage and of high and pure principles. His public life was passed in the defence of the oppressed. In the House of Commons he was known as the Member of India, and to that country he was always a staunch friend. He took part in the great Peace movement, lectured and wrote in support of the abolition of the death penalty, and other great humanitarian reforms. In spite of derision and abuse from a section of the public, he went on his way, always actuated by high motives and conscientious aims, and I felt it an honour to work, in however humble a way, with such an apostle of freedom." (13)

Louisa joined the National Secular Society and became a reader of its newspaper, The National Reformer. Under the influence of Besant, it published many articles on issues such as marriage, women's rights and the political status of women. Besant also advocated socialism that caused a dispute with Bradlaugh who was a member of the Liberal Party: "When I became co-editor of this paper I was not a Socialist; and, although I regard Socialism as the necessary and logical outcome of the Radicalism which for so many years the National Reformer has taught, still, as in avowing myself a Socialist I have taken a distinct step, the partial separation of my policy in labour questions from that of my colleague has been of my own making, and not of his, and it is, therefore, for me to go away. Over by far the greater part of our sphere of action we are still substantially agreed, and are likely to remain so. But since, as Socialism becomes more and more a question of practical politics, differences of theory tend to produce differences in conduct; and since a political paper must have a single editorial programme in practical politics, it would obviously be most inconvenient for me to retain my position as co-editor. I therefore resume my former position as contributor only, thus clearing the National Reformer of all responsibility for the views I hold." (14)

Under the influence of Annie Besant's writings Louisa took a strong interest in women's rights. In 1888 she married John Samson, an executive member of the National Secular Society. (15) Louise also worked as a journalist and contributed illustrated articles to The Daily Mail and at different times was on the editorial staff of "three well-known weekly papers". (16) Louisa took an increasing interest in women's suffrage and became a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). (17)

Women's Freedom League

John Samson died in 1905 and in 1907 Louisa married George Thomson-Price. (18) Later that year Louisa joined the Women's Freedom League (WFL), an organisation formed by former members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) that were unhappy about the leadership of of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. Most of its members were socialists who wanted to work closely with the Labour Party who "regarded it as hypocritical for a movement for women's democracy to deny democracy to its own members." (19)

The Women's Freedom League established its own newspaper, The Vote. The first edition, published on 8th September 1909, consisted of four pages. Two months later it had grown to eight pages. (20) The newspaper pointed out: "We hope and believe that through its pages the public will come to understand what the Parliamentary Franchise means to us women. Now it will be both a symbol of citizenship and the key to a door opening out on such service to the community as we have never yet been allowed to render, and therefore it is our earnest hope that our paper will keep its place in the hearts of men and women long after the first victory has been won." (21)

Two of the Women's Freedom League leaders, Teresa Billington-Greig and Charlotte Despard, and were both talented writers and were the main people responsible for producing the newspaper. Louisa Thomson-Price was an experienced journalist and became consultant editor. She also became director of its publishing company, Minerva Publishing. (22) One of Britain's leading writers, Cicely Hamilton, became the first editor of the newspaper. (23)

Louisa Thomson-Price became an important figure in the Women's Freedom League. It was pointed out that she had "boundless energy, an unshaken belief in humanity, a great optimism, a profound knowledge of the questions of the day, and a rare intuition with regard to the "chosen people and the chosen causes" are perhaps the most distinguishing characteristics of the most delightful of colleagues." (24)

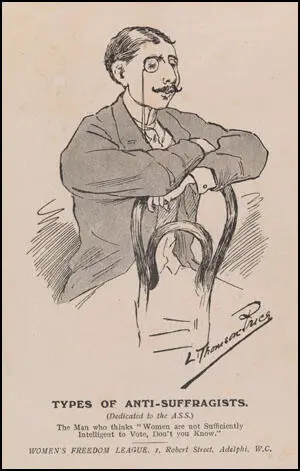

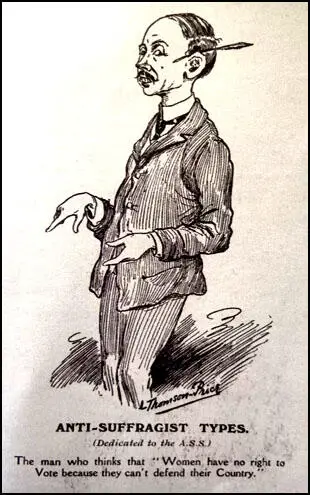

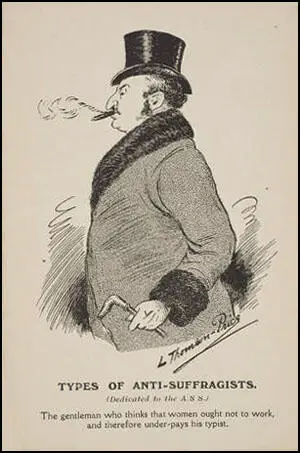

On 4th November, 1909, The Vote carried its first cartoon. It was drawn by Louisa Thomson-Price. Three weeks later, in the issue of 25 November, she contributed the first of a series of twelve cartoons, depicting various stereotypical"Anti-Suffragists", that ran until March 1910. The WFL then issued these cartoons as black and white postcards. The 16th December, 1909, issue, contained a cartoon by Louisa Thomson-Price of H. H. Asquith pulling a "Votes for Women" plum out of his "General Election pie". This image was produced as a WFL poster for use in the January 1910 General Election Election. (25)

The Vote never rivalled either The Common Cause or Votes for Women, but members of the WFL did recognise the importance of their own paper in keeping members informed and in generating a sense of a united organisation. It also used it to explain the philosophy of the group: "We must rebel, we must not rest until the ballot box is no longer the symbol of sex tyranny but the symbol of political sex equality." (26)

As Edith How-Martyn explained: "We cannot reiterate too often that our object is to give a practical example of the impasse which would be produced in our national life if women seriously began to refuse their consent to the autocratic government by men. Passive resistance against unjust authority is binding on those who believe in doing something to win their freedom. Until women win representation they are morally justified in demonstrating that their exclusion from citizenship certainly does involve national injury." (27)

Louisa Thomson-Price was a regular contributor to The Vote newspaper. One of her articles dealt with the way women who campaigned for the vote were described as "unwomanly". She pointed out that "In the old days, the stigma unwomanly was cast upon every association in which women were endeavouring to gain a livelihood outside the only two admissible ones for respectable young persons. To be a governess or a lady or a lady's companion was perfectly permissible, and a young woman lost none of her womanliness in following those ill-paid and ill-conditioned occupations. Education in the real sense of the word was not necessary for the old-time governess."

She went on to argue: "The 'womanly' woman need to faint at the sight of a mouse, or was supposed to do so. She had lily-white hands, tiny feet, and a wasp-like waist. It was 'womanly' to defy Nature by squeezing a twenty-seven-inch waist into a twenty-inch corset, and 'unwomanly' to suggest that comfort and health were higher than restriction and convention."

Thomson-Price suggested that Florence Nightingale was an "unsexed creature" according to the general consensus of opinion of her day. "The Lady of the Lamp was the very embodiment of unwomanliness in daring to undertake the self-imposed task of tending the wounded soldiers of the Crimea. Today the hospital nurse is no longer considered unwomanly, but the medical woman has still to fight a prejudice which dies hard."

"As I have said, there are certain avocations which public opinion, or, at least, public male opinions, considers unwomanly. Strangely enough, these avocations are always the better-paid ones. It is not 'unwomanly' to stand at a wash-tub all day, to scrub the stone steps and long-corridors of city offices, to bathe verminous patients in infirmaries, to wash and attend to the dressing of foul wounds in hospital wards, to make chains at Cradley Heath, or to work at the pit's mouth in a mining district. It is not 'unwomanly' to manufacture match boxes at 2¼ a gross (finding one's own paste and string) or to make blouses at 1s 6d a dozen, but it is 'unwomanly' for a person of the female sex to pass the necessary examinations to qualify as a doctor, to give medical advice on women's aliments, to perform a surgical operation, or to become a university lecturer." (28)

Louisa Thomson-Price believed strongly that men should be allowed to join the Women's Freedom League. She wrote in The Vote: "The WFL owes much to the brave and valiant men who have helped us by their sympathy and active support on many public occasions. I am of the opinion that if our League elected to be the pioneer Suffrage Society in throwing open its portals to men and women alike, our work would gain immeasurably by consolidation and expansion....Now is the day and the hour for this great step." (29) Despite this plea the WFL remained a women only organisation. (30)

Women's Tax Resistance League

In October 1909 when the Women's Freedom League (WFL) established the Women's Tax Resistance League (WTRL). (31) The first member to take part in the campaign was Dr. Octavia Lewin. It was reported in The Daily Chronicle that the "First Passive' Resister", was was to be taken to court. It was announced in the same report that "the Women's Freedom League intends to organise a big passive resistance movement as a weapon in the fight for the franchise." (32)

Over the next few years over 220 women took part in this campaign. This included Louisa Thomson-Price, Janie Allan, Charlotte Despard, Beatrice Harraden, Teresa Billington-Greig, Edith How-Martyn, Cicely Hamilton, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Emma Sproson, Margaret Nevinson, Octavia Lewin, Henria Williams, Violet Tillard, Edith Zangwill, Sophia Duleep Singh and Clemence Housman.

Sylvia Pankhurst, the author of The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931): has argued: "Tax resistance and resistance to enumeration under the Census of that year were mild forms of militancy now in vogue. The Women's Freedom League had hoisted the standard of 'no vote, no tax' in the early days of its formation, and Mrs. Despard and others had suffered a succession of distraints, to the accompaniment of auction sale protest meetings... In May, 1911, two women were imprisoned for refusal to take out dog licences. A little later, Clemence Housman, sister of the author-artist, Laurence Housman, was committed to Holloway till she should pay the trifling sum of 4s. 6d., but was released in a week's time, having paid nothing." (33)

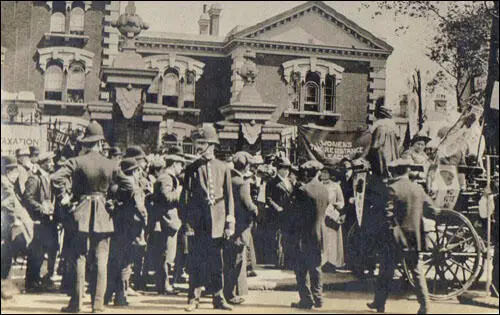

The The Vote reported that Louisa Thomson-Price was heavily involved in the activities of the Women's Tax Resistance League: "At Hampstead on May 18 a large group of tax resisters had their goods sold at Fitzjohns Estate Auction Rooms. They were Mrs Thomson Price, Mrs and Miss Hicks, Mrs How Martyn , Mrs Milligan, Mrs Hartley, the Misses Collier, and the Misses Dawes Thompson. A procession with a band marched from Finchley Road station to the auction rooms at Swiss Cottage and after the sale an excellent meeting was held at the corner of the Avenue Road. From a gaily decorated wagonette speeches were made by Mrs Thomson Price, Mrs Nevinson and Mrs Kineton Parkes, explaining the reason of the protest." (34)

Successful Businesswoman

Louisa Thomson-Price was a vociferous shareholder in a number of important companies. This was very unusual at the time towards the end of 1915 that her shareholder activism started attracting attention in newspapers. According to Lizzie Broadbent: "Louisa had a sharp tongue, a good brain and a thick skin: a triple threat or a triple benefit depending on whether you were a hapless CEO or a frustrated shareholder." (35)

Lucy H. Yates, a member of the Women's Freedom League who gave lectures on "The Financial Independence of Women" was a great admirer of Thomson-Price: "It is unusual, even in these days, for a woman to wield such an influence in the business world... An ardent enthusiast, with very broad sympathies, she never stayed her hand when her pen could be used, nor her voice when speech could help any cause." (36)

In 1916 Louisa Thomson-Price became a deputy chairman of Slaters, a chain of 60 restaurants especially popular with women. During the First World War she revolutionised the company, "supervised the buying, evolved fresh colour schemes for the dining rooms, and designed pretty uniforms for the waitresses." By 1916 it had a turnover of over 600,000. (37) When she became a director of Slaters it was paying no dividend and with £1 shares at 5s 3d. but ten years later it was making a profit of over £26,000. (38)

In June 1920, Thomson-Price attended the AGM for Ebbw Vale Steel Iron and Coal. She stood up to make a proposal that it should be easier for some its 34,000 employees to become shareholders: "quite a few companies have arranged for their employees to be paid a certain commission on their earnings, such commission to be translated at the end of the year into shareholdings… I think such a scheme would be very valuable one." (39)

In 1922, unhappy with the performance of her holding in the Smithfield and Argentine Meat Company, which had not paid a dividend the previous year, Louisa campaigned for an investigation into the company. A committee was finally set up, which she headed, and after "four months of hard labour", brought a damning report and a series of recommendations to the Board in November 1922. Impressed by her involvement in this investigation Louisa Thomson-Price was added to the Board of Directors. (40) She was also a Governor of the Universal Cookery and Food Association and Vice-Chairman of the art firm of Siegmund Hildesheimer & Co Ltd. (41)

Louisa Thomson-Price suffered from curvature of the spine since birth. In later life she had mobility problems. She continued to speak in public. As one of her friends pointed out: "Few people who heard her resonant voice speaking from a platform had any idea that to walk across a room was a painful, sometimes an impossible feat. With unflinching courage she held to her duties to the last... That work has been to lift higher the banner of business integrity and to make the lot of every worker with whom she had anything to do a pleasant, healthful, interesting, and properly paid occupation." (42)

In the last few months of her life she still took a close interest in Slaters. "When too ill to walk shae arranged to be taken to the boardroom, and by her indomitable will carried out her duties. The last few months, unable to leave her room, she still went through all the business of the week with the officials of her firm." (43)

Louisa Thomson-Price died on 14th June 1926. She left over £34,761, from which a bequest of £500 was paid to the Women's Freedom League and £1,000 to endow a bed at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital and a £1,000 to the Homes for the Aged Poor. She also left the household furniture and wearing apparel and the income from £6,000 to "my dear friend Mary Ann Mcintosh, in recognition of many years of faithful friendship and of great tenderness, unremitting care, and unselfish devotion". (44)

Primary Sources

(1) The Reading Mercury (5th May 1866)

Mrs Matilda Louisa Sowdon examined – I am the petitioner. My maiden name was Hutton. I was married to the respondent at St Saviour's Church, Jersey, on the 8th November, 1860. The respondent was then residing at Jersey, and was of independent means. He had been in the army. I have had three children by the respondent – one son and two daughters. Shortly after our marriage my husband began to give way to intoxication, and after a time he used very bad language to me; his conduct soon became worse; he frequently stayed away from home for several days together – often remained out late at night, and sometimes all night. On one occasion he remained away a whole week…

Shortly after the birth of my first child, the respondent struck me with his fist in the side, while I was sitting in bed nursing my child, and then locked me in the bedroom and took the key away, and my aunt was obliged to force the door open…

As soon as I was able I followed him to England, and found him at Reading; this was in October 1862. We took a house in Shirley, near Southampton. After a while we went to live in Sydney Terrace, Reading…

At the beginning of 1864, the respondent struck me with his fist while I was in bed, and I was obliged to go into the next room in the middle of the night. The next night he struck me, and also kicked me and swore at me… I gave evidence against him before the magistrates, and he was committed to prison for 14 days….

The Judge Ordinary said he was satisfied. There would be a degree nisi, with costs, the petitioner to have the custody of the children till further order.

(2) The Vote (14th May 1910)

To have lived and to live in stirring times and to be part of them, to have known intimately and spoken from the same platform as the great reformers of our century, to have the courage to voice unpopular views, and at the same time to carry on a busy professional life full of exactions and complexities and never to fail those who depend on one's public or one's professional exertions is a fine record for anyone, man or women; and this is the record that Mrs Thomson Price has made during her working life, and one of which she is slow to speak. The daughter of a captain in the 2nd Life Guards (Blue), and belonging to a family whose records were unbrokenly orthodox and Tory, she developed her own education and intelligence on the lines that appealed to her most, and found herself presently a secularist and a Radical.

"For Charles Bradlaugh I have always had the most profound admiration," said Mrs Thomson-Price." When he was President of the National Secular Society I was one of its members, and spoke for that body many times. Misunderstood and maligned as he was, he was a man of magnificent courage and of high and pure principles. His public life was passed in the defence of the oppressed. In the House of Commons he was known as the Member of India, and to that country he was always a staunch friend. He took part in the great Peace movement, lectured and wrote in support of the abolition of the death penalty, and other great humanitarian reforms. In spite of derision and abuse from a section of the public, he went on his way, always actuated by high motives and conscientious aims, and I felt it an honour to work, in however humble a way, with such an apostle of freedom.

My first husband, Mr John Samson, was on the Executive Council of the NSS. I have often spoken at open-air meetings for the National Secular Society when it was necessary for a strong body of stalwarts to form a cordon round the platforms. Suffragists are not the only reformers who have had to gradually win a hearing.

"And when John Burns came out of the prison to which he had been sentenced as a result of claiming the right of free speech in Trafalgar Square, I was one of those who assembled to welcome him. It is strange to think that the John Burns of today, who would deny us free speech, was the same man who desired it sufficiently for the working men of England that he was not afraid to suffer for it."

I was for several years secretary of the North Hackney Women's Liberal and Radical Association," continued Mrs Thomson Price," and I was a member of the old constitutional society for obtaining the franchise; but I left the latter because I believed that the time had come for new departures. There had been a slump in constitutional methods since Gladstone betrayed the Liberal women in 1884, when in the Bill to extend the franchise he refused to accept the amendment to include women as voters on the same terms as men. He declared that it would "sink the ship", and to avoid any catastrophe to himself he threw the women overboard.

"My professional work? It has been very varied. I have been a journalist for twenty-four years, and the the early part of it I did a good deal of political writing – at the time an unusual occupation for a woman – on the Liberal and Radical , and I also did cartoons for the Political World and other papers.

The humorous cartoons which Mrs Thomson-Price has done for us will be remembered. They were for several months a popular feature in The Vote, that of "Little Jack Horner" having been by special request transformed into a poster during the General Election. She was editor and past proprietor of a weekly paper for women and was one of the first contributors to Ariel, Mr Israel Zangwill's papers. She has done illustrated articles for the Daily Mail, articles on finance for financial papers, and is at present on the editorial staff of three well-known weekly papers, beside being consultant editor of The Vote and a frequent contributor of interesting matters to its columns.: Miss Thomson-Price is also a director of an accident insurance company and of the Minerva Publishing Company. She is also a member of Council of the Society of Women Journalists and of the Journalists' Advisory Board of the Lyceum Club.

"Do I approve of militancy? Most certainly I do, and I was glad to be one of those who picketed the House of Commons – one of the most effective militant protests which have been made since the militant movement began. During our long wait we learned a good deal of human nature. Like the House itself and the Abbey close by, the "waiting women" were one of the "sights" of London to the country cousin and the stanger. On the whole we met with much sympathy during that trying time, and some of it came from the most unexpected quarters. An old couple, obviously working folk, halted in front of me one afternoon, and the old gentleman took off his hat to me. "We be with you, ma'am," he said.

Boundless energy, an unshaken belief in humanity, a great optimism, a profound knowledge of the questions of the day, and a rare intuition with regard to the "chosen people and the chosen causes" are perhaps the most distinguishing characteristics of the most delightful of colleagues, whose career – to describe it fully – would require a volume of "our organ".

(3) Louisa Thomson-Price, The Vote (8th October 1910)

One has heard so much during the last five years of the "unwomanly" woman, who in the minds of some people, at any rate, it personified by the "rampant, raging suffragette," that is one is led sometimes to wonder who is to be the ultimate authority as to what constitutes a "womanly" woman. In the old days, the stigma "unwomanly" was cast upon every association in which women were endeavouring to gain a livelihood outside the only two admissible ones for respectable young persons. To be a governess or a lady or a lady's companion was perfectly permissible, and a young woman lost none of her womanliness in following those ill-paid and ill-conditioned occupations.

Education in the real sense of the word was not necessary for the old-time governess. The curriculum of the young ladies' seminary, so delightfully described to us in "Vanity Fair," included only a smattering of general information, the "use of the globes," and a "knowledge of deportment". The early Victorian young lady with adorable ringlets, sloping shoulders, and frequent fits of "the vapours" was, no doubt, from the male standpoint of that period, an embodiment of perfect womanliness. The "womanly" woman need to faint at the sight of a mouse, or was supposed to do so. She had lily-white hands, tiny feet, and a wasp-like waist. It was "womanly" to defy Nature by squeezing a twenty-seven-inch waist into a twenty-inch corset, and "unwomanly" to suggest that comfort and health were higher than restriction and convention.

Florence Nightingale was an "unsexed creature" according to the general consensus of opinion of her day. The "Lady of the Lamp" was the very embodiment of unwomanliness in daring to undertake the self-imposed task of tending the wounded soldiers of the Crimea. Today the hospital nurse is no longer considered unwomanly, but the medical woman has still to fight a prejudice which dies hard.

As I have said, there are certain avocations which public opinion, or, at least, public male opinions, considers unwomanly. Strangely enough, these avocations are always the better-paid ones. It is not "unwomanly" to stand at a wash-tub all day, to scrub the stone steps and long-corridors of city offices, to bathe verminous patients in infirmaries, to wash and attend to the dressing of foul wounds in hospital wards, to make chains at Cradley Heath, or to work at the pit's mouth in a mining district. It is not "unwomanly" to manufacture match boxes at 2 ¼ a gross (finding one's own paste and string) or to make blouses at 1s 6d a dozen, but it is "unwomanly" for a person of the female sex to pass the necessary examinations to qualify as a doctor, to give medical advice on women's aliments, to perform a surgical operation, or to become a university lecturer.

(4) Louisa Thomson-Price, The Vote (4th November 1911)

The WFL owes much to the brave and valiant men who have helped us by their sympathy and active support on many public occasions. I am of the opinion that if our League elected to be the pioneer Suffrage Society in throwing open its portals to men and women alike, our work would gain immeasurably by consolidation and expansion....Now is the day and the hour for this great step.

(5) The Vote (22nd May 1914)

At Hampstead on May 18 a large group of tax resisters had their goods sold at Fitzjohns Estate Auction Rooms. They were Mrs Thomson Price, Mrs and Miss Hicks, Mrs How Martyn , Mrs Milligan, Mrs Hartley, the Misses Collier, and the Misses Dawes Thompson. A procession with a band marched from Finchley Road station to the auction rooms at Swiss Cottage and after the sale an excellent meeting was held at the corner of the Avenue Road. From a gaily decorated wagonette speeches were made by Mrs Thomson Price, Mrs Nevinson and Mrs Kineton Parkes, explaining the reason of the protest.

(6) Lizzie Broadbent, Louisa Thomson-Price (9th December, 2020)

Louisa must have received a good education because in 1886, aged 22, she published a book, ‘Comic Sketches and Sober Thoughts’. Two years later she married John Samson, a journalist and editor of the South American Journal, 16 years her senior. They lived in Stoke Newington, where Louisa became involved in the North Hackney Women’s Liberal Association. She was a gifted illustrator, providing drawings for books and newspaper features where she signed herself ‘L.S.’. She also edited the official magazine of the Ladies Needlework Guild, the Spinning Wheel for four years. The Guild had over 100,000 members and the weekly ‘penny paper’ was highly regarded for its literary content, positioning itself as The Queen in miniature.

In 1897, Louisa and John were living on Fitzroy Road in Primrose Hill, where Louisa hosted the wedding breakfast for one of her half-sisters, Jessie, in September. Jessie was also a writer and artist, signing her work ‘Jess C’ and her marriage to another magazine editor, Stanhope Sprigg, made for a wedding of ‘some interest in literary and art circles.’ Two of their children, Christopher and Theodore, also became authors.

By 1899, Louis and John had moved to Parkhill Road in Hampstead, the area where Louisa remained based for the rest of her life. Louisa wanted to register this address in her own name so that she could pay the rates and as a result be placed on the role of local electors. She was eventually successful and penned a letter to the local paper to inform other women of the precedent she had set, even it had been at the cost of ‘almost endless correspondence and many hours of valuable time, which, as a busy journalist I could ill spare, to say nothing of solicitor’s fees etc.’

John died in 1905 and in 1907 Louisa married George Thomson-Price and changed her name again. George moved in with her to the house she had shared with John. The information on him is scanty but he was clearly very supportive of Louisa’s commitment to the cause of women’s suffrage: he won a competition to see who could spend most on items sold by advertisers in The Vote, the official newspaper of the Women’s Freedom League, in 1910.

(7) Elizabeth Crawford, Suffrage Stories: Women’s Tax Resistance League (2013)

Mrs Louisa Thomson Price was born Louisa Catherine Sowdon in 1864 and died in 1926. She was the daughter of a Tory military family but from an early age rebelled against their way of thinking and became a secularist and a Radical. She was impressed by Charles Bradlaugh of the National Secular Society. In 1888 she married John Samson, who was a member of the executive of the NSS. She worked as a journalist from c 1886 – as a political writer, then a very unusual area for women, and drew cartoons for a radical journal, ‘Political World'. She was a member of the Council of the Society of Women Journalists. After the death of her first husband, in 1907 she married George Thomson Price. She had no children from either marriage.

Louisa Thomson Price was an early member of the Women's Freedom League, became a consultant editor of its paper, The Vote, and was a director of Minerva Publishing, publisher of the paper. She contributed a series of cartoons to The Vote, which were then produced as postcards. The ‘Jack Horner' cartoon was also issued as a poster for, I think, the January 1910 General Election. Louisa Thomson Price took part in the WFL picket of the House of Commons and was very much in favour of this type of militancy. In her will she left £250 to the WFL. and £1000 to endow a Louisa Thomson Price bed at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital.

(8) Claire Louise Eustace, The Evolution of Women's Political Identities in the Women's Freedom League (1993)

Louisa Thompson-Price came from a strictly Tory family, but claimed that through education she became a "secularist" and a "radical". She was an admirer of Charles Bradlaugh, one of the earliest birth control advocates. She served as secretary of the North Hackney Women's Liberal and Radical Association and was a member of the NUWSS. She resigned from both when militancy began, and was one of the earliest members of the WFL. Later she took part in the WFL's picket of the House of Commons in 1909 and shortly after became a director of the Minerva Publishing Company. Louisa Thompson-Price gained a brief notoriety following her article in The Vote in 1911 calling for men to be admitted to the WFL. There are no records of any subsequent involvement, but Louisa seems to have maintained links with the WFL, as after her death in 1926 she left it a legacy of £250!- in her will.

(9) Lucy H. Yates, The Vote (16th July 1926)

It is unusual, even in these days, for a woman to wield such an influence in the business world, but in her case it was the more remarkable in that those great abilities were a treasure held in an earthen vessel of the frailest, most sorely afflicted type. Few people who heard her resonant voice speaking from a platform had any idea that to walk across a room was a painful, sometimes an impossible feat.

With unflinching courage she held to her duties to the last, and passed away able to say: "I have finished the work that Thou gavest me to do." That work has been to lift higher the banner of business integrity and to make the lot of every worker with whom she had anything to do a pleasant, healthful, interesting, and properly paid occupation.

But those who knew Mrs Thomson-Price as personal friend and literary comrade saw another side of her jewel-like personality. It was one fall of charm and unexpectedness. A little sketch, a few verses, a humorous recollection were always ready to light up the most ordinary subject. An ardent enthusiast, with very broad sympathies, she never stayed her hand when her pen could be used, nor her voice when speech could help any cause.

(10) The Vote (16th July 1926)

Our friend and gallant colleague, Mrs Thomson-Price, was born into a high Tory family, the daughter of a Captain in the Life Guards. She early began to think for herself, was a lecturer for the Women's Liberal Association, spoke on Suffrage (with Lord Haldane in 1891, and welcomed John Burns when he came out of prison to establish the right of free speech in Trafalger Square used by us to such good purpose ten years later.

For 40 years she was a busy journalist, attached for 28 years to the editorial staffs of two London dailies; but she was also an artist and a poet, writing illustrated articles for the dailies, authoritative articles for the financial press, political articles and political cartoons, designing humorous Suffrage cartoons (types of anti-suffragettes, etc.) for The Vote, and contributing to it many much appreciated articles. She edited several papers, and was Consulting Editor and Director of The Vote .

An exceeding able businesswoman, she was a Governor of the Universal Cookery and Food Association, sat on many directorates, and was Vice-Chairman of the art firm of S. Hildersheimer & Co, Ltd.

Mrs Thomson Price specialised in company law and procedure, and was a keen critic of shareholders' meetings. In 1922 she organised and presided over a Committee of Investigation into the affairs of the Smithfield and Argentine Meat Co., Ltd under whose advice the company was, later, successfully reconstructed.

Ten years ago she became a director of Slaters, Ltd, at that time paying no dividend, and with £1 shares at 5s 3d. Here too, she presided over a Committee of Investigation, being elected Deputy Chairman in the following year. Last May, after a discreditable attempt of a few persons to oust her from command, she was unanimously elected to the Chair, and announced a profit for the year of over £26,000.

All this time she never missed a weekly meeting of her Board, and when too ill to walk arranged to be taken to the boardroom, and by her indomitable will carried out her duties. The last few months, unable to leave her room, she still went through all the business of the week with the officials of her firm.

A wonderful union of high qualities of head and heart inspired affection and admiration in all who knew her. With all her splendid courage, self-control, integrity, boundless energy, and industry, Mrs Thomson-Price was a most loyal comrade – cherry, friendly, optimistic, and of ready wit. She followed eagerly the fortunes of The Vote, and was delighted with our "strike issues".

(11) Hampstead News (2nd September 1926)

Mrs Louisa Thomson-Price of Belsize Park Gardens, Hampstead, for nine years vice chairman and afterwards chairman of Slaters Ltd, caterers and restaurants, a leader of the Suffragists and at one time editor of Votes for Women, died on June 14 leaving property of the value of £34,761, with net personally £31,734. Among other bequests, she leaves the household furniture and wearing apparel and the income from £6,000 to "my dear friend Mary Ann Mcintosh, in recognition of many years of faithful friendship and of great tenderness, unremitting care, and unselfish devotion"; and, on her death, as to £1,000 part thereof, to the Homes for the Aged Poor, £1,000 to endow a bed in the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital, Euston Road, and £500 to the Women's Freedom League.

(12) David Simkin, Family History Research (22nd April, 2023)

Louisa Catherine Sowdon was born in Reading, Berkshire, on 18th April 1864 and baptised at Saint Mary's Church, Reading on 30th June 1864. She was the youngest of three children born to Matilda Louisa Hutton (1841-1897) and William Henry Sowdon (1837-1869), described variously as a former army officer, a "landed proprietor", a "gentleman" and a man of "independent means".

Louisa's father, William Henry Sowdon was born in the St. Giles parish of Reading, Berkshire, on 22nd July 1837, the son of Louisa and Harry Sowdon (1799-1862), a former wine & spirit merchant who owned a brewery in Bridge Street, Reading. William Sowdon was educated at Marlborough College and after attending a military college, he enlisted in the British Army in 1855. William Sowdon served as a junior officer in the 95th Regiment of Foot. He claimed to have risen to the rank of Captain but according to a report in the London Gazette, dated 13th March 1857, Ensign William Henry Sowdon of the 95th Foot had been superseded "he being absent without leave". After leaving the British Army, William Sowdon took up farming and in the 1861 Census he gave his occupation as "Landed Proprietor". On 8th November 1860, at St Saviour's parish church on the island of Jersey, William Henry Sowdon married 19-year-old Matilda Louisa Hutton, the daughter of Mary Ann Davis and the late Henry Hutton (died 1860), a pianoforte dealer of St. Helier. When the 1861 Census was taken in the Channel Islands, William Sowdon and his young wife were recorded at Over Dale Cottage, St. Helier, Jersey. On the 1861 Census return, William H. Sowdon, is described as a "Landed Proprietor", aged 25. (His actual age was 23). The young couple employed a single house servant at their cottage. On 27th August 1861, at St. Helier, Jersey, William's wife, Mrs Matilda Sowdon, gave birth to their first child, a son named Harry Wilson Sowdon. Matilda later testified that shortly after the birth of their son, her husband "treated her with great neglect and frequently used abusive and insulting and threatening language to her". Matilda also alleged that, whilst she was feeding her new-born baby, her husband "struck her with his fist".

According to Mrs Matilda Sowdon's divorce petition, in August 1862 William Sowdon deserted her and returned to his hometown of Reading in Berkshire. The couple were eventually reconciled at the end of 1862 and settled in the port of Southampton in Hampshire. On 24th February 1863, whilst residing in Southampton, Matilda gave birth to their second child, a daughter named Eleanor Matilda Sowdon. After the birth of her daughter, Mrs Sowdon reported that her husband continued to abuse her verbally and physically and on one occasion, in a Southampton shop, "William Henry Sowdon struck her a violent blow in the face with his fist". Mrs Sowdon complained that her husband was frequently intoxicated and would abandon her for days "without letting her know where he was going".

By the beginning of 1864, Mrs Matilda Sowdon, together with her husband and their two young children, was residing in the Berkshire town of Reading. While living in Reading, Matilda continued to suffer abusive, threatening, and violent behaviour from her husband. Whilst lying in bed and pregnant with her third child, Matilda claimed that William Sowdon violently kicked her and "threatened to throw her out of the window". She further alleged that before the birth of her third child, her husband had "wilfully infected" her with a venereal disease. Matilda gave birth to a baby daughter on 18th April 1864. This child was Louisa Catherine Sowdon. According to Mrs Sowdon's statement to the divorce court, her husband deserted her on 14th February 1864, and she did not see him again until 8th October 1865, when "he came to her residence at No. 4 Zinzan Terrace, Reading …and abused and threatened and violently assaulted her".

On 20th October 1865, Mrs Matilda Sowdon petitioned for a divorce from her husband William Henry Sowdon on the grounds of his abusive and threatening behaviour, his violence towards her, his desertion, his cruelty, and his adultery with several women. In a signed statement to the court dated 25th November 1865, William Henry Sowdon denied all the charges against him, but the judge decided that the marriage should be dissolved on the grounds of William's adultery and cruelty towards his wife. Matilda's divorce from William Sowdon was finalised on 19th February 1867. Two months after the divorce, on 22nd April 1867, William Henry Sowdon married Annie Wright at the parish church in Romsey, Hampshire. A couple of years later, on 17th November 1869, at Winchester in Hampshire, William Henry Sowdon died at the age of 32. The cause of death was given as diphtheria and paralysis.

Matilda ("Tilly") Louisa Hutton (1841–1897): Born 16th August 1841, Plymouth, Devon, England – Died 30th April 1897, Reading Berkshire.

In 1907, at Hampstead, Louisa Catherine Samson married George William Thomson Price (1857–1916) The family name of her husband was 'Price' - George's surname Thomson-Price appears to have been an affectation.

George William Thomson-Price died at 42 Park Hill Road, Hampstead, Middlesex, on 17th June 1916.

To his widow, Louisa, he left effects valued at £1,759. 1s 6d.Louisa Catherine Thomson-Price, widow, of 17 Belsize Park Gardens , Hampstead, Middlesex, died on 14th June 1926. The executors of her will were: William Thomas Robert Gilkes, retired shipper, Ralph Hall,

barrister-at-law, and Mary Ann McIntosh. spinster. According to the probate calendar, Louisa Thomson-Price's effects were valued at £34,761. 10s .5d.In the Scotland, National Probate Index, she is recorded as Louisa Price aka Louisa Catherine Thomson-Price.

This Scottish record confirms that she died at home at 17 Belsize Park Gardens , Hampstead, Middlesex.

Louisa's death was registered under the surname 'Price'According to Paul Marshall, [Family Tree & Photos on Ancestry], Louisa suffered from curvature of the spine from birth.

Student Activities

References

(1) The Reading Mercury (5th May 1866)

(2) The Vote (14th May 1910)

(3) The Reading Mercury (5th May 1866)

(4) Matilda Hutton Sowdon, divorce petition (May 1866)

(5) Roger Fulford, Votes for Women (1957) page 92

(6) Annette Mayer, The Growth of Democracy in Britain (1999) page 57

(7) Lisa Tickner, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign (1988) page 5

(8) The Vote (14th May 1910)

(9) Lizzie Broadbent, Louisa Thomson-Price (9th December, 2020)

(10) The Times (14th November, 1887)

(11) The Vote (14th May 1910)

(12) Edward Royle, Charles Bradlaugh : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(13) The Vote (14th May 1910)

(14) Annie Besant, The National Reformer (October, 1887)

(15) Claire Louise Eustace, The Evolution of Women's Political Identities in the Women's Freedom League (1993) page 418

(16) The Vote (14th May, 1910)

(17) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 192

(18) Lizzie Broadbent, Louisa Thomson-Price (9th December, 2020)

(19) Martin Pugh, The Pankhursts (2001) page 167

(20) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 192

(21) Charlotte Despard, The Vote (30th October 1909)

(22) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 192

(23) Maroula Joannou, Cicely Hamilton: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23rd September 2004)

(24) The Vote (14th May 1910)

(25) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) pages 192-193

(26) The Vote (4th November, 1909)

(27) Edith How-Martyn, The Vote (4th March 1911)

(28) Louisa Thomson-Price, The Vote (8th October 1910)

(29) Louisa Thompson-Price, The Vote (4th November 1911)

(30) Claire Louise Eustace, The Evolution of Women's Political Identities in the Women's Freedom League (1993) page 418

(31) Teresa Billington Greig, The Non-Violent Militant: Selected Writings of Teresa Billington-Greig (1987) page 104

(32) The Daily Chronicle (28th March 1908)

(33) Sylvia Pankhurst, The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931) page 351

(34) The Vote (22nd May 1914)

(35) Lizzie Broadbent, Louisa Thomson-Price (9th December, 2020)

(36) Lucy H. Yates, The Vote (16th July 1926)

(37) Elizabeth Crawford, Art and Suffrage: A Biographical Dictionary of Suffrage Artists (2018) page 193

(38) The Vote (16th July 1926)

(39) The Globe (17th June, 1920)

(40) Lizzie Broadbent, Louisa Thomson-Price (9th December, 2020)

(41) The Vote (16th July 1926)

(42) Lucy H. Yates, The Vote (16th July 1926)

(43) The Vote (16th July 1926)

(44) Hampstead News (2nd September 1926)