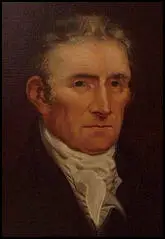

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy was born in Larbert in Scotland on 3rd March 1752. Hardy's father had been a sailor who died at sea on 1760. After a brief education at the local school, Hardy went to work for his grandfather who taught him the trade of shoemaking.

At the age of twenty-two, Hardy moved to London where he found work as a shoemaker. In 1781 he married the daughter of a carpenter. The couple had six children but they all died young. After working for several different employers, in 1791 Hardy decided to open his own shop in the Piccadilly Road. Soon after starting his business, Hardy heard about Thomas Paine and eventually read his book The Rights of Man.

Trade was difficult and Hardy gradually came to the conclusion that his economic problems were being caused by a corrupt Parliament. Hardy was especially angry about the costs of the war with France. Thomas Hardy later wrote that he now knew that the men in the House of Commons were "falsely calling themselves the representatives of the people, but who were, in fact, selected by a comparatively few individuals, who preferred their own particular aggrandisement to the general interest of the community."

Thomas Hardy and three friends began meeting to discuss whether or not working men should have the vote. After much discussion they decided that they should have that right and on the 25th January 1792 they held a public meeting on parliamentary reform. Only eight people attended but the men decided to form a parliamentary reform group called the London Corresponding Society.

As well as campaigning for the vote, the strategy was to create links with other reforming groups in Britain. Hardy was appointed as treasurer and secretary of the organisation. The society passed a series of resolutions and after being printed on handbills, they were distributed to the public. These resolutions also included statements attacking the government's foreign policy. A petition was started and by May 1793, 6,000 members of the public had signed saying their supported the resolutions of the London Corresponding Society.

In July, 1793, Hardy made a speech where he argued: "We conceive it necessary to direct the public eye, to the cause of our misfortunes, and to awaken the sleeping reason for our countrymen, to the pursuit of the only remedy which can ever prove effectual, namely; a thorough reform of Parliament, by the adoption of an equal representation obtained by annual elections and universal suffrage. To obtain a complete representation is our only aim - condemning all party distinctions, we seek no advantage with every individual of the community will not enjoy equally with ourselves."

At the end of 1793 Thomas Muir began plans to hold a a convention in Edinburgh for supporters of parliamentary reform. The London Corresponding Society sent two delegates but the men and other leaders of the convention were arrested, tried for sedition, and sentenced to fourteen years transportation. The reformers were determined not to be beaten and Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall began to organise another convention.

When the authorities heard what was happening, Hardy and the other two men were arrested and committed to the Tower of London and charged with high treason. The government recruited cartoonists such as James Gillray to mount a propaganda campaign against the leaders of the London Corresponding Society. The main objective of this campaign was to link the reformers with with the actions of the revolutionaries in France.

As a result, of this campaign, a mob attacked Thomas Hardy's house. Mrs. Hardy, pregnant with her sixth child, was forced to escape out of a back window. Hardy later explained: "A mob of ruffians assembled before my house and assailed the windows with stones and brick-bats. They then attempted to break down the shop door, and swore, with the most horrid oaths, that they would either burn or pull down the house. Weak and enfeebled from her situation, Mrs Hardy shouted to her neighbours, who advised her to escape through a small back window. This she attempted, but being very large around the waist, she stuck fast, and it was only by main force that she could be dragged through, much injured by the bruises she had received." Soon after this incident, Mrs. Hardy died in childbirth and the child was still-born.

Thomas Hardy's trial began at the Old Bailey on 28th October, 1794. The prosecution, led by Lord Eldon, argued that the leaders of the London Corresponding Society were guilty of treason as they organised meetings where people were encouraged to disobey King and Parliament. Attempts were made to link the activities of However, the prosecution was unable to provide any evidence that Hardy and his co-defendents had attempted to do this and the jury returned a verdict of "Not Guilty".

The poor case against Hardy, and the death of his wife had created a great deal of public sympathy for the shoemaker and a large crowd was waiting outside the Old Bailey. The jubilant crowd took the horses from his carriage and drew him through the streets to his home where they observed a short period of silence in memory of his wife and dead child.

After his trial Hardy ceased to be active in politics. He ran a small shoeshop in Covent Garden until his retirement in 1815.

Thomas Hardy died in Pimlico on 11th October 1832.

Primary Sources

(1) Thomas Hardy, speech, 8th July, 1793.

We conceive it necessary to direct the public eye, to the cause of our misfortunes, and to awaken the sleeping reason for our countrymen, to the pursuit of the only remedy which can ever prove effectual, namely; a thorough reform of Parliament, by the adoption of an equal representation obtained by annual elections and universal suffrage. To obtain a complete representation is our only aim - condemning all party distinctions, we seek no advantage with every individual of the community will not enjoy equally with ourselves.

(2) Resolutions passed by the London Corresponding Society in January, 1793.

(I) That nothing but a fair, adequate and annually renovated representation in Parliament, can ensure the freedom of this country.

(II) That we are fully convinced, a thorough Parliamentary Reform, would remove every grievance under which we labour.

(III) That we will never give up the pursuit of such Parliamentary Reform.

(IV) That if it be a part of the power of the king to declare war when and against whom he pleases, we are convinced that such power must have been granted to him under the condition, that he should ever be subservient to the national advantage.

(V) That the present war against France, and the existing alliance with the Germantic Powers, so far as it relates to the prosecution of that war, has hitherto produced, and is likely to produce nothing but national calamity, if not utter ruin.

(VI) That it appears to us that the wars in which Great Britain has engaged, within the last hundred years, have cost her upwards of three hundred and seventy million! not to mention the private misery occasioned thereby, or the lives sacrificed.

(VII) That we are persuaded the majority, if not the whole of those wars, originated in Cabinet intrigue, rather than absolute necessity.

(VIII) That every nation has an unalienable right to choose the mode in which it will be governed, and that it is an act of tyranny and oppression in any other nation to interfere with, or attempt to control their choice.

(IX) That peace being the greatest blessing, ought to be sought most diligently by every wise government.

(X) That we do exhort every well wisher to this country, not to delay in improving himself in constitutional knowledge.

(3) Thomas Hardy, Memoirs (1832)

A majority of the people are not represented in Parliament; that the majority of the House of Commons are chosen by a number of voters, not exceeding twelve thousand; and that many large and populous towns have not a single vote for a representative, such as Birmingham, 40,000 inhabitants, Manchester 30,000, Leeds 20,000, besides Sheffield, Bradford, etc.

(4) Thomas Hardy, Memoirs (1832)

A mob of ruffians assembled before my house and assailed the windows with stones and brick-bats. They then attempted to break down the shop door, and swore, with the most horrid oaths, that they would either burn or pull down the house. Weak and enfeebled from her situation, Mrs Hardy shouted to her neighbours, who advised her to escape through a small back window. This she attempted, but being very large around the waist, she stuck fast, and it was only by main force that she could be dragged through, much injured by the bruises she had received.