Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt, the daughter of Paul and Martha Arendt, was born in Hanover on 14th October 1906. Her father was a successful businessman but held progressive political opinions. Paul and Martha were both members of the German Social Democratic Party. Paul had been suffering from syphilis for many years and died in a psychiatric hospital in 1913 when Hannah was only seven. It has been claimed by Derwent May that "those who knew her well could see that Hannah kept a deep sorrow buried inside her." (1)

Hannah's mother had no religious faith but she brought her daughter up to be proud of her Jewish heritage. She had little interest in tradition or ritual. Hannah felt that her dark brown eyes made her look a little different than other children. There was the odd anti-Semitic comment but anti-Semitism was not a serious problem in those years. (2)

Hannah's mother made it clear how she respond to anti-Semitism: "When my teachers made anti-Semitic remarks - mostly not about me, but about other Jewish girls, eastern Jewish students in particular - I was told to get up immediately, leave the classroom, come home, and report everything exactly. Then my mother wrote one of her many registered letters; and for me the matter was completely settled. I had a day off from school, and that was marvelous! But when it came from children, I was not permitted to tell about it at home. That defended yourself against what came from children." (3)

In 1920, when she was thirteen, her mother married again. Her new husband, Martin Beerwald, a successful Jewish businessman, had two teenage daughters (his first wife had died a few years before), Clara, who was now twenty, and Eva who was nineteen. They were all supporters of the Social Democratic Party and Hannah enjoyed the political discussions that took place in the family. (4)

Hannah Arendt was an extremely intelligent teenager and became interested in Greek philosophy. "Headstrong and independent, she displayed a precocious aptitude for the life of the mind. And while she might risk confrontation with a teacher who offended her with an inconsiderate remark - she was briefly expelled for leading a boycott of the teacher's classes." (5)

Hannah's fellow students found her a very attractive young woman. Hannah was described as having "striking looks: thick, dark hair, a long, oval face, and brilliant eyes". One student claimed that she had "lonely eyes" but "starry when she was happy and excited". Another friend described them as "deep, dark, remote pools of inwardness." (6)

Arendt later recalled that life was difficult as a Jew living in Germany: "One thing was certain: if one wanted to avoid all ambiguities of social existence, one had to resign oneself to the fact that to be a Jew meant to belong either to an over privileged upper class or to an underprivileged mass which, in Western and Central Europe, one could belong to only through an intellectual and somewhat artificial solidarity." (7)

At the age of sixteen, Martha Arendt, arranged for her to spend two terms studying in Berlin, where the family had friends. Hannah lived in a student residence and took classes in Latin and Greek at the university, where she was introduced to theology by Romano Guardini, a Christian existentialist, who introduced her to the work of Søren Kierkegaard and Karl Jaspers. (8)

Hannah Arendt at University

At the age of sixteen, Martha Arendt, arranged for her to spend two terms studying in Berlin, where the family had friends. Hannah lived in a student residence and took classes in Latin and Greek at the university, where she was introduced to theology by Romano Guardini, a Christian existentialist, who introduced her to the work of Søren Kierkegaard and Karl Jaspers. (8)

In 1924 Hannah went to University of Marburg where she studied philosophy under Martin Heidegger. He was thirty-five years old and married to Elfride Heidegger when they met: "He was an exceptionally brilliant man but, in his professional and private life, a cautious one... He was also, it would seem, rather vain and self-conscious: he was short, and always insisted on sitting down when he was photographed, so that this would be less apparent." (9)

Hannah attended her first Heidegger lecture in November 1924. He argued that Socrates, Plato and Aristotle had taken philosophy in the wrong direction and "turned away from awe-filled contemplation of the actual existence of things toward an abstract metaphysics of ideas and ideal types". This "pre-Christian belief in eternal ideal types and the unity of the universe made him especially attractive eight hundred years later to St. Augustine, who sought to establish an intellectual basis for Christian thought." (10)

Heidegger preferred the pre-Socratics because their thought focused on actual existence. He went on to argue that the decline of civilisation from the earliest heights of pre-Socratic thought had been accelerated by Christianity, which distracted one from the essential fact of existence by directing attention to an afterlife. Hannah later claimed that it was his early lectures that convinced her that he was "the hidden king of thinking". (11)

Heidegger quoted Cato the Elder as saying: "Never is he more active than when he does nothing, never is he less alone than when he is by himself". The central characteristic of this type of thinking is the presence of a second internal voice to hear and test ideas: responding, revising, or rejecting. "The second voice reacts to what the first reacts to what the first proposes, if indeed the two can be told apart definitely. It is the twin-one duality of the mind that makes it possible for the self to reflect on itself, to assess its ideas, even to judge itself." (12)

After one lecture at the beginning of February 1925, Heidegger approached Hannah Arendt and suggested she came to see him in his office. He asked about the lectures and about the philosophers she had been reading. A few days later they began an affair. "He (Heidegger) responded to Hannah's youth, her beauty and her mind. Many years later he declared to her that it was she who had inspired his thought in these years of the mid-1920s... They were lovers for several months... and they would meet in the attic room where she lodged." (13)

Heidegger wrote: "You are my pupil and I your teacher, but that is only the occasion for what has happened to us. I will never be able to call you mine, but from now on you will belong in my life, and I shall grow with you." In another letter he said: "Love is rich beyond all other possible human experiences... because we become what we love and yet remain ourselves... Love transforms gratitude into loyalty to ourselves and unconditional faith in the other... Nothing like it has ever happened to me." (14)

What we know about the first months of their love affair comes mostly from Heidegger's letters to Arendt, which she saved. For whatever reasons, he did not save her letters. Heidegger made it clear that he would never leave his wife, Elfride Heidegger, and their two children. "There are shadows only where there is also sun." Hannah accepted this and agreed to keep the relationship a secret. (15) According to Mary McCarthy, her love affair with Heidegger was the most important that she had in her life. (16) Although she accepted that it was a man of weak character and a "notorious liar". (17)

Arendt later justified her relationship with a married man with children. She believed that the love between them deserved to be preserved and nurtured independently of any social convention or competing obligation. Although his wife was an intelligent woman she could "not participate in his deepest thought or be the companion that he needed to overcome his alienation from the world." Hannah "did not expect their love to last forever, neither could she deny it or feel in any way ashamed". However, as Daniel Maier-Katkin has pointed out: "It was naive... not to see that a deceitful and adulterous husband might also be untrustworthy and undependable as a lover." (18)

Other students who Heidegger had a major influence over included Hans Jonas, Karl Löwith, and Herbert Marcuse. Like Arendt, they were all "non-Jewish Jews". Heidegger was considered to be an excellent teacher: "Heidegger's impact as a teacher and mentor was, according to most extant accounts, inordinately profound. Few scholars who experienced his mesmerizing lectures and seminars remained untransformed. By the same token, students who fell under his powerful philosophical shadow often had difficulty extricating themselves and establishing an independent intellectual identity - a dilemma that even his most gifted students were forced to confront. Needless to say, such problems were compounded in the case of his extraordinarily talented Jewish students, men and women who often first experienced their Jewish identity in the crosshairs of German anti-Semitism." (18a)

Elfride Heidegger was not very well liked, indeed was deeply resented in some circles. Although she had some Jewish friends, Elfride was openly anti-Semitic in the sense that she did not want German culture to be influenced by what she considered to be "alien" ideas and aesthetics. She was a traditionalist who loved to go on walks while singing popular folk songs. She disliked the pluralism and modernism of the Weimar Republic and was an early supporter of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. (19)

One day the Heidegger family and a group of philosophy students went for a hike and a picnic lunch in the Black Forest. They held an athletic competition and one of the students, Günther Stern, was an easy winner. Elfride was very impressed with this young man who she already knew to be a very fine musician, as well as a talented student in philosophy and literature. At the end of the day Elfride told Stern that he was an exceptional specimen of humanity and that such a young man ought to be a member of the Nazi Party. He replied that as he was Jewish he did not think the party would have a place for him. (20)

Jorg Heidegger was born in January 1919. The following year Elfride became pregnant but Martin was not the father as he had been working abroad at the time of conception. Elfride's physician and childhood friend, Friedel Caesar, was the real father. Heidegger seems not to have been disturbed by Elfride's extramarital pregnancy. It is possible that they had an open marriage. He wrote to her that he understood her love for Friedel. "In the end, they concealed this indiscretion from the world, continuing as husband and wife... Thus they remained, or seemed to remain, within the community of traditional values, and to avoid the stigma of adultery in her case and of having been a cuckold in his." (21)

In the summer of 1925, Hannah relationship with Martin Heidegger began to weaken. In a letter to him she explained the way she was feeling. Derwent May explained: "After her happy childhood, she says that she had become dull and self-preoccupied for a long time. noticing things but not responding to them with any feeling, and finding a protection for herself in this state of mind. Heidegger had released her from this spell, so that the world had become full of colour and fascination and mystery for her again." (22)

Hannah Arendt left University of Marburg and moved to the University of Freiburg, where she studied under Edmund Husserl, a man who had inspired Heidegger's philosophy. Husserl was very impressed with Heidegger recent work and wrote to Erich Jaensch saying. "He is without doubt the most important figure among the rising generation of philosophers... predestined to be a philosopher of great stature, a leader far beyond the confusions and frailties of the present age." (23)

Arendt wrote that Heidegger recognised before anyone else that philosophy was almost dead. It had been formulated into schools of thought and compartmentalized into such disciplines such as logic, ethics, and epistemology, and was not so much taught as "finished off by abysmal boredom." Heidegger did not participate in the "endless chatter about philosophy," rehearsing the teachings of others. He read all the earlier thinkers, and he read them, Arendt said, better than anyone ever had, and perhaps better than anyone ever will again. "His intention was not merely to comprehend or absorb the lessons taught by others, but to interrogate the masters, to think with and against them." (24)

On 9th January, 1926, Arendt visited Heidegger and complained that she felt forgotten. In a letter to Arendt he tried to explain his position: "It is not from indifference, not because external circumstance intruded between us, but because I had to forget and will forget you whenever I withdraw into the final stages of my work. This is not a matter of hours or days, but a process that develops over weeks and months and then subsides. And this withdrawal from everything human and breaking off of all connections is, with regard to creative work, the most magnificent human experience... but with regard to concrete situations, it is the most repugnant thing one can encounter. One's heart is ripped from one's body." (25)

Being and Time

The book Heidegger was working on with Hannah, Being and Time, was published in 1927. Heidegger approached philosophy in a different way. His work was deeply influenced by Charles Darwin that had provided an alternative to Genesis's account of creation and Albert Einstein had reconceptualized the material universe. The ascent of industrialized technology had elevated reason above faith in Western culture. "The various sciences broke away from philosophy, which had for centuries been their home; and all that seemed to be left behind was metaphysics.... Metaphysics came to signify the capacity of the mind to penetrate beyond the physical realm into an extended universe of intangibles filled with questions about the existence of God, the soul, what we are doing when we are thinking, or whether we can be certain that the world as it appears to us is the same as the world as it actually exists." (26)

Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche were inventive philosophers in the nineteenth century thinking outside of the mainstream. These two became increasingly important over time, but neither was well known or widely read in their own lifetimes or in the early years of the twentieth century. Anthony Grayling argues that Heidegger's work was important in the development of what became known as existentialism: "Commentators on existentialism find its roots in the writings of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger... Existentialism... is a concomitant of an atheist view that whatever meaning attaches to human existence is found in it or imposed on it by human beings themselves, for one premise of atheism is that no purpose is established for mankind from outside... The four values which individuals... can impose on the meaninglessness of existence to give it value: namely love, freedom, human dignity, and creativity." (27)

Interestingly, the word "love" appears only once in all 500 pages of the book. Heidegger asks a series of questions: "What is existence?" "What is time?" "What is a thing?" "What is a work of art: Is it only the canvas and oils, or does something less tangible also exist there?" But he never questioned the meaning or existence of love. He appeared obsessed with death, "which carries us out of this world, that he failed to notice that it is love which connects us to it." (28) Karl Jaspers commented that because love was absent from Being and Time, the book's style was unlovable. (29)

The anchoring concepts of Being and Time are "being" and "disclosure". These are discussed in existentialist terms. Disclosure is effected by anxiety. It has been pointed out that "anxiety is not fear, which is always fear of something particular, but rather is an indefinite and general mood of dread or anguish." We are thrown into the world without any answers available to the question, "Why am I here, why am I here now?" Heidegger suggests that we deal with this question by the "process of looking at the things around us to find possibilities for escaping our dread." (30) Heidegger also pointed out that the fact of death establishes the meaning of what has been." (30a)

Within a few years, this book was recognized as a truly epoch-making work of 20th century philosophy. It earned Heidegger, in the fall of 1927, full professorship at Marburg, and one year later, after Husserl’s retirement from teaching, the chair of philosophy at University of Freiburg. (31) It catapulted Heidegger to a position of international intellectual visibility and provided the philosophical impetus for a number of later programmes and ideas in the contemporary European tradition, including the existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre. (32)

The Concept of Love in Augustine

Hannah Arendt moved to the University of Heidelberg where she became friends with a group of intellectuals that included: Karl Jaspers, Heinrich Blücher, Benno von Wiese, Rudolf Bultmann, Karl Frankenstein, Erich Neumann, Hugo Friedrich, Erwin Loewenson, Hans Jonas and Kurt Blumenfeld, the president of the German Zionist Federation. Jonas said that Hannah had a "genius for friendship". Arendt soon began an affair with Loewenson, a young writer from Berlin. (33)

Arendt also had a sexual relationship with Von Wiese, "who was tall, thin, fair-haired, refined, aristocratic, brilliant, and although only a few years older than Hannah, was already professorial and a respected figure in the field of literary history." They were together for two years, "but in the end he claimed to need a wife more dedicated to domesticity." It has also been claimed that he might have been unwilling to marry a Jewish woman. (34)

The most important person she came to know in Heidelberg was Karl Jaspers, who taught her philosophy. He shared with Heidegger the fundamental existentialist convictions. He had been influenced by the works of Karl Marx and "saw modern technology as rendering men mindless and mechanical, utterly alienated from all sense of their Being, as it incorporated them into its own mindless systems." Arendt never considered him so profound a thinker as Heidegger, but preferred his outlook on life. Jaspers was excited by the freedom given to man by finding himself in an empty universe. "The fact that there was no authority, no ultimate truth, provided men with the adventure of finding their own truth - and the further adventure of reaching out to other men to share their thought and discoveries." Jaspers taught his students: "Think for yourself, but in your thinking place yourself also in the situation of every other man." (35)

Hannah Arendt occasionally met Martin Heidegger but in April 1928 he told her because of his fame he would not be able to visit her again. A few days later she wrote to him about their relationship: "I have been anxious the last few days, suddenly overcome by an almost bafflingly urgent fear... I love you as I did on the first day - you know that, and I have always known it... The path you showed me is longer and more difficult than I thought. It requires a long life in its entirety... I would lose my right to live if I lost my love for you, but I would lose this love and its reality if I shirked the responsibility to be constant it forces on me." (36)

Under Jasper's supervision, Arendt worked on her doctoral dissertation, which she had decided would be a study of the idea of love in the thought of Augustine of Hippo in The Confessions (397-398 AD), Arendt admitted, "that for her, every thought had something to do with personal experience, that every thought was a glance backward, an afterthought, a reflection on early matters or events." (37) In 1929 Arendt published The Concept of Love in Augustine. "It is an austere, systematic study, relating Augustine's different concepts of love to the human experience of time." (38)

Arendt argued that Augustine believed that: "Happiness springs into existence when the gap between lover and beloved has been closed; then desire yields to satisfaction and calm quietude. Love is each human being's possibility of gaining happiness. Once we have the object of our desire, however, we begin to feel threatened by the possibility of its loss.. Fear of loss corresponds to the desire to have. The great paradox is that since all things of the world are temporary, love threatens to leave us in a perpetual state of fear and mourning... If man most craves freedom from fear, he will turn away from love of worldly things that can only be lost, and will embrace the eternal Being that exists outside of past, present, and future, the Being from which we come and toward which we are propelled, each at the still point of a turning universe... For Augustine, love carries man beyond the realm of fear and time into a transcendent union in which each present moment is experienced in the presence of the timeless eternal." (39)

In January 1929, Hannah Arendt met Günther Stern, whom she had not seen since 1925. Within a month they were living together and in September they were married. A few days before the wedding, Arendt wrote to Heidegger telling him that the continuity of love between the two of them was still the most meaningful thing in her life: "Do not forget how much and how deeply I know that our love has become the blessing of my life. This knowledge cannot be shaken, not even today... I would indeed so like to know - almost tormentingly so, how you are doing, what you are working on, and how Freiburg is treating you." (40)

Rahel Varnhagen

Arendt began work on her second book, a biography of the German writer, Rahel Varnhagen (1771-1833). A close friend, Anne Mendelssohn, had purchased for her the complete correspondence of Varnhagen in several leather-bound volumes from a bankrupt bookseller. Anne told Hannah that she would find a kindred spirit, an unspoiled, unconventional, intelligent woman, interested in people, passionate and vulnerable. Anne was right and even though she had been dead for nearly a hundred years, Hannah described her as her "closest friend". (41)

Varnhagen, like, Arendt, was a Jewish woman who passionately loved men, who did not return her love. Her words where she expressed her love for Don Raphael d'Urquijo, could have been used by Arendt to describe her feelings for Heidegger: "This man, this creature wielded the greatest magic over me, still wields it. I... gave him my whole heart. And once the heart is given, only love and worthiness can give it back; otherwise it is gone from you... In short, so long as I cannot love someone more intensely, the part of myself necessary for happiness remains in his power." (42)

In the 1790s one of the salons run by women in Berlin was in Varnhagen's spacious apartment. People in attendance were likely to be nobles, authors, musicians, diplomats, high civil servants, scientists, military leaders and master artisans. Regular visitors to Varnhagen's home included the explorer, Alexander von Humboldt, the philosopher, Wilhelm von Humboldt, Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia and prominent authors, Friedrich Schlegel, Friedrich Schleiermacher and Ludwig Tieck. Varnhagen had a series of love affairs with various aristocrats, including the Swedish Ambassador Karl Gustave von Brinckmann, the diplomat Friedrich von Gentz and Count Karl von Finckenstein of Prussia. (43)

Hannah Arendt made it clear in her book that Rahel Varnhagen attempted to use her sexuality to escape from the stigma of being a Jew. In her love affairs and her eventual marriage to the writer, Karl August Varnhagen von Ense, she hoped to transcend Jewish identity and establish herself in good society. Although she converted to Christianity, she found this was unavailable to her because in "good society" she remained a Jew. For many years she took this to be the great misfortune of her life. In her last years, Rahel began to appreciate her position of marginality. (44)

This view is reflected in her deathbed declaration recorded by her husband: "What a history! A fugitive from Egypt and Palestine, here I am and find help, love, fostering in you people. With real rapture I think of these origins of mine and this whole nexus of destiny, through which the oldest memories of the human race stand side by side with the latest developments. The greatest distances in time and space are bridged. The thing which all my life seemed to me the greatest shame, which was the misery and misfortune of my life - having been born a Jewess - this I should on no account now wish to have missed." (45)

Hannah Arendt argued that her study of Rahel Varnhagen had shown that while Jews in Germany had been invited into citizenship as equal human beings, there had never been a place for them in "good" society and that "pariah" is the natural state of a Jew in the Diaspora. Arendt later wrote: "For the formation of a social history of the Jews within nineteenth-century European society, it was, however, decisive that to a certain extent every Jew in every generation had somehow at some time to decide whether he would remain a pariah and stay out of society altogether, or become a parvenu and conform to society on the demoralizing condition that he hides his origin." (46)

While studying the life of Varnhagen that Arendt developed her views towards anti-Semitism. "Writing about Rahel's experience at the beginning of German-Jewish emancipation while observing the looming end of enlightenment in her own immersed her in the Jewish question. Her identity as a Jew arose not out of religious conviction or desire for affiliation, but from an embrace of the role of self-conscious pariah. That the Jews were becoming more than ever a hated and despised minority strengthened Arendt's ties." (47)

The position of Jews in society had changed profoundly between Varnhagen's time at the beginning of the 19th century and Arendt's at the beginning of the 20th century. Jews, often atheistic Jews, had made a major contribution to western culture. This included Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein, Alfred Adler, Wilhelm Reich, Erich Fromm, Felix Frankfurter, Isaiah Berlin, Bertolt Brecht, Kurt Weill, Franz Kafka, Max Reinhardt, Theordor Herzl, Stefan Zweig, Anna Seghers, etc. For example, a third of all Nobel prizes won by Germans had been awarded to Jews. (48)

Adolf Hitler

In the General Election that took place in September 1930, the Nazi Party increased its number of representatives in parliament from 14 to 107. The behaviour of the Nazis became more violent. On one occasion 167 Nazis beat up 57 members of the German Communist Party in the Reichstag. They were then physically thrown out of the building. The stormtroopers also carried out terrible acts of violence against socialists and communists. In one incident in Silesia, a young member of the KPD had his eyes poked out with a billiard cue and was then stabbed to death in front of his mother. Four members of the SA were convicted of the rime. Many people were shocked when Hitler sent a letter of support for the four men and promised to do what he could to get them released. (49)

Hannah Arendt became more interested in politics. Unlike her parents, she had not been active in the German Social Democratic Party. The number of political assassinations perpetrated by right-wing extremists grew rapidly. Arendt responded to the increase in anti-Semitism by saying "if one is attacked as a Jew, one must defend oneself as a Jew, not as a German, not as a world-citizen, not as an upholder of the Rights of Man, or whatever." (50)

According to Arendt: "In a society on the whole hostile to the Jews - and that situation obtained in all countries in which Jews live, down to twentieth century - it is possible to assimilate only by assimilating to anti-Semitism also... And if one really assimilates, taking all the consequences of denial of one's own origin and cutting oneself off from those who have not or have not yet done it, one becomes a scoundrel." (51)

Many of Arendt's friends were Zionists, but she refused to join the movement as she disapproved of their impulse to withdraw into a culture of their own. "Arendt... resented the politics of Jewish leadership, which, having always feared the anti-Semitism of the mob, preferred to play ball with anyone in power rather than forging alliances with other people at the bottom. She rejected the underlying (sometimes unspoken) postulate of the Zionist call for a homeland as antagonistic to pluralism in so far as it proposed a benign ethnic cleansing... The judgment Arendt made was that Jews should not look only for a solution to their own problems, but rather that they should show solidarity with all oppressed people to look for solutions that would promote justice everywhere." (52)

On 4th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler had a meeting with Franz von Papen and decided to work together for a government. It was decided that Hitler would be Chancellor and Von Papen's associates would hold important ministries. "They also agreed to eliminate Social Democrats, Communists, and Jews from political life. Hitler promised to renounce the socialist part of the program, while Von Papen pledged that he would obtain further subsidies from the industrialists for Hitler's use... On 30th January, 1933, with great reluctance, Von Hindenburg named Hitler as Chancellor." (53)

Exile in Paris

Hannah Arendt had watched these events with great concern but it was the Reichstag Fire on 27th February, 1933, after which Hitler ordered the arrests of leading members of the German Communist Party (KPD) and Social Democratic Party (SDP), that convinced her to leave Nazi Germany: "The burning of the Reichstag, and the illegal arrests that followed the same night. The so-called protective custody... This was an immediate shock for me, and from that moment on I felt responsible. That is, I was no longer of the opinion that one can simply be a bystander." (54)

Arendt's husband, Günther Stern, immediately fled to Paris. She stayed with the idea of helping in some way. Arendt eventually decided to help the German Zionist Federation in collecting materials that would show the extent of anti-Semitism in all aspects of German society. Her research involved risk as the new government had already passed a law that criminalized criticism of the state. Her activities were detected and she was arrested in the spring of 1933 and held at police headquarters for eight days. (55)

Hannah Arendt was able to develop a good relationship with the man who arrested her: "I got out after eight days because I made friends with the official who arrested me. He was a charming fellow! He'd been promoted from the criminal police to a political division... Unfortunately, I had to lie to him. I couldn't let the organization be exposed. I told him tall tales, and he kept saying, 'I got you in here. I shall get you out again. Don't get a lawyer! Jews don't have any money now. Save your money!' Meanwhile the organization had gotten me a lawyer. .. And I sent the lawyer away. Because this man who arrested me had such an open, decent face. I relied on him and thought that here was a much better chance than with some lawyer who himself was afraid." (56)

As soon as Hannah was released she crossed into Czechoslovakia by night and then traveled on to Paris where she rejoined her husband. Although they lived together Hannah wanted a divorce. Stern felt otherwise and she chose not to walk out on him. (57) She later told Heinrich Blücher: "I wanted to dissolve my marriage three years ago - for reasons which I will perhaps tell you someday. My only option. I felt, was passive resistance, termination of all matrimonial duties. It seemed to me that that was my right; but nothing else. Separation would have been the most natural outcome for the other party. Which the other party, however, never thought necessary to opt for." (58)

Hannah became friends with several Jewish intellectuals. This included Alexandre Koyre who explained history as a series of dramatic - even cataclysmic - disruptions and discontinuities; not steady evolution or progress, but suddenly something new growing on the ruins of what had been established, which too will run its course and disappear, making room for something different and unpredictable. This explained the rise of fascism, Koyre argued, not, as the Nazis claimed, a fulfillment of destiny and directionality in history. (59)

Raymond Aron was a committed socialist who had been disillusioned with the developments in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. He argued that just as religion is the opium of the masses, ideology is the opium of the intellectuals. Whereas some intellectuals were willing to defend Stalinism, others, such as Martin Heidegger, were willing to justify Hitler's racial policy. Aron was among the first to see that Stalin was no better than Hitler. (60) Arendt was sympathetic to Aron's anti-Stalinism; and his early recognition of fundamental similarities in the new political systems that had emerged in the twentieth century influenced the development of her thinking about totalitarianism. (61)

Another important influence was the philosopher, Walter Benjamin. He was attracted to Marxism because of its "messianic identification with the oppressed and its promise of justice". Arendt loved "both his character of his thinking and the beauty of his language and recognised him as a polymath genius, an erudite literary stylist who dabbled in philosophy, history, theology, textual interpretation, and literary and cultural criticism, producing minor masterpieces wherever he went." (62) Arendt saw in Benjamin a mixture of "merit, great gifts, clumsiness, and misfortune." (63)

Benjamin was a collector of books, observations, quotations and ideas. He approached the past as a vast and growing pile of broken fragments of earlier and other experience, which he wanted to collect, catalogue, and organize in the hope of resurrecting dead moments of past existence to gain understanding. In the 1930s he produced more than 15,000 handwritten index cards filled with phrases copied from old newspapers and magazines and cross-indexed on a wide variety of subjects. (64)

While in Paris she worked first as a secretary in a Zionist organization, and then as an assistant to Baroness Germaine de Rothschild, the daughter of Édouard de Rothschild, overseeing contributions to Jewish charities. Hannah got on well with the baroness but was fairly hostile to the rest of her illustrious family. The Rothschild were the main force behind the Consistoire de Paris, the major philanthropic enterprise supported by rich French Jews. They and other Jewish leaders were hostile to immigrants, fearing that those from the East would provoke anti-Semitism with their Old World dress and manners, and that left-wing German-Jewish politics would inflame right-wing anti-Semitism in France. (65)

Martin Heidegger and Fascism

In the winter of 1932, Arendt wrote to Martin Heidegger saying that there were rumours circulating that he was becoming a Nazi and an anti-Semite. He replied rejecting this claim but in reality he was collaborating in secret with Nazi professors and sympathizers to destabilize the elected rector at Freiburg, Wilhelm von Möllendorff, a member of the German Social Democratic Party, who had refused to dismiss Jews working at the university. Heidegger suggested that if he was elected rector, he would join the party and sack Jewish members of staff. (66)

Under pressure from the German government, Von Möllendorff, resigned and on 21st April 1933, Heidegger was elected as rector of University of Freiburg by the faculty, and on 1st May he joined the Nazi Party. If not an anti-Semite, he was certainly an opportunist. He also campaigned for Germany's withdrawal from the League of Nations in the plebiscite of November 1933. (67) Over the next year he carried out some of the Nazi educational reforms with what has been described as "enthusiasm". (68)

The Nazi Party made good use of Heidegger. "There were pictures of him in the newspapers: Heidegger, the leading German philosopher, with a Hitler-style mustache, wearing a brown tunic with a high collar and a Nazi Party pin with eagle, globe, and swastika. It might have been laughable in a Charlie Chaplin sort of way were it not for his international prominence as an intellectual... Most significantly, as rector, Heidegger signed all of the letters dismissing Jewish faculty at the University of Freiburg, including the letter to his friend, mentor, steadfast champion, and enthusiastic supporter, the world-famous emeritus professor of philosophy, Edmund Husserl, a baptized Austrian Jew, professing Lutheran, and German patriot whose enthusiastic support over the years prepared the path for Martin's elevation to his chair in philosophy." (69)

Rudiger Safranski, the author of Martin Heidegger: Between Good and Evil (1999) argues that Heidegger was not anti-Semitic "in the sense of the ideological lunacy of Nazism". Karl Jaspers said that Heidegger was not openly anti-Semitic, but crude anti-Semitism went against his "conscience and taste". However, in the 1930s, he appeared to be insensitive to the suffering of many of his Jewish friends and colleagues, but that Heidegger was not anti-Semitic "in the sense of the ideological lunacy of Nazism." (70)

Heidegger abolished the Faculty Senate and instituted a dictatorial system of governance. He wrote letters that effectively destroyed the academic careers of dissident graduate students and young faculty members. He went so far as to recommend that the famous chemist Hermann Staudinger (who was not a Jew or active in left-wing politics) be removed from his position as professor because of his pacifist and anti-nationalist beliefs in the First World War. The Ministry of Culture agreed with this decision, but the Nazi government, "afraid of worldwide repercussions" allowed Staudinger to retain his position. (71)

For many years Heidegger was a regular visitor to the home of Karl Jaspers and his Jewish wife, Gertrud Jaspers. The final time that Heidegger visited their home, in 1933, Gertrude spoke directly to him about the hospitality he had accepted in her house over many years, and about how awful and frightening she found the Nazis with whom he had associated himself. Gertrude began to cry and Heidegger commented: "Sometimes crying helps to make you feel better." Heidegger left, never saying goodbye. (72)

Walter Eucken, an economist who worked with Heidegger at the University of Freiburg, who later joined the German Resistance group led by Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Hans Dohnányi, Friedrich Olbricht, Henning von Tresckow, Friedrich Olbricht, Werner von Haeften, Claus von Stauffenberg, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Ulrich Hassell, Hans Oster, Peter von Wartenburg, Hans Dohnányi, Erwin Rommel, Franz Halder, Klaus Bonhoeffer, Hans Gisevius, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Ludwig Beck and Erwin von Witzleben. Eucken believed that Heidegger saw himself as the natural philosophical and intellectual leader of the Reich and hoped to shape and define Nazi philosophy for the coming millennium. (73)

Despite the fact that Hitler was willing to make use of Heidegger's support, he much preferred the the ideas of Alfred Rosenberg, who had first developed his anti-Semitic views during the First World War when while in Russia in 1917 he first saw a copy of The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. According to Konrad Heiden: "To Rosenberg it was a sign from heaven. Both the place and the hour were significant. Moscow, 1917.... The globe was afire. The Tsar's empire was crumbling. Perhaps there would never again be peace. Perhaps this book would tell him why. The demon, who had incited the nations against each other, had spoken. Perhaps he, Alfred Rosenberg, understood him better than others, for in his own soul he could feel more strongly than others the mesh woven by hatred and love between the nations.... Surely one of the most astounding, far-reaching, and bloody conspiracies of all time was bound to that hour. He who could read would go far." (74)

The book claimed that the First Zionist Congress in 1897 was a gathering of Jewish conspirators. In his book, Die Spur de Juden in Wandel der Zeiten (1920) he pointed to "Bolshevik Jewry" as the moving force behind the Russian Revolution. "Over the next two years he published no fewer than four other books in which he denounced the Jews as wanting in morals, as the founders and perpetuators of the criminal Freemason societies, and as a people of decisive influence in Russia who were plotting to overthrow governments throughout the world by means of Zionism." (75)

Daniel Maier-Katkin has argued that Alfred Rosenberg's philosophy that so appealed to Hitler "revolved around the ideas that God had not created individuals but separate races, that only the race has a soul, that Aryan culture is based on a higher innate moral sensibility and more energetic will to power, and the higher races must rule over and not interbreed with the lower races in order to preserve their superior physical and spiritual heredity." (76)

In November 1923, Hitler appointed Rosenberg as editor of the Volkischer Beobachter (Racial Observer). It was an anti-socialist and anti-Jewish newspaper. For example,one headline was "Clean Out the Jews Once and for All." The article urged a "final solution" of the Jewish problem by "sweeping out the Jewish vermin with an iron broom." The newspaper also campaigned for the concentration camps to house Germany's Jewish population. (77)

Under the editorship of Rosenberg the newspaper became increasingly anti-Semitic. Rosenberg saw English capitalists, as long as they were not Jews, as the Aryan rulers of "coloured sub-humanity". He argued in July 1930 that "German master-men must systematically and peaceably share Aryan world domination... England's task is the protection of the white race in Africa and West Asia; Germany's task is to safeguard Germanic Europe against the chaotic Mongolian flood and to hold down France, which has already become an advance guard of Africa... None of the three states can solve the task of destiny alone." (78)

In the summer of 1933, Heidegger began his campaign to become chair at the University of Berlin and the leadership of the Prussian Academy of University Lecturers. However, he had several enemies within the Nazi Party, including Erich Rudolf Jaensch, who taught philosophy at the University of Marburg and Ernst Krieck, who was a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg. Jaensch and Krieck wrote to Rosenberg saying that Heidegger's appointment would be "catastrophic" as he was a man who had helped to maintain the old system, especially its "Jewish cliques". Heidegger was described as the "quintessential decadent archetypal representative of the age of decay." (79)

Heidegger traveled to Berlin hoping to see Hitler but his approach was rejected. It now became clear that his enemies in the party had blocked him. In April 1934, Heidegger resigned as rector at the University of Freiburg. He later claimed that he stepped down because Bernhard Rust, the Minister of Education, ordered him to replace the deans of the law and medical schools with party members whom he considered unqualified, but it is more likely he resigned because he realized that he was not trusted by Hitler. (80)

Hannah Arendt wrote some years later, that fascism in Germany did not allow for free initiative in any field of life. It was, she thought, a sign of Heidegger's naivety that he ever thought the Nazis would have a place of leadership for a man who thought independently and whose thought was too complicated for them to understand. "Totalitarianism in power invariably replaces all first-rate talents, regardless of their sympathies, with crackpots and fools whose lack of intelligence and creativity is the best guarantee of their loyalty." (81)

Martin Heidegger remained a supporter of Hitler. In the summer of 1936, he visited Rome wearing a swastika pin on his jacket. He told his former student Karl Löwith, who was living in exile, that fascism was the right course for Germany, if one could "hold out long enough". He made it clear that he had not abandoned his ideology, his commitment to German rebirth, nor even his confidence in Hitler's leadership. Although he did not play a major role in Nazi Germany there is no evidence that he ever uttered a word of resistance. (82)

Heinrich Blücher

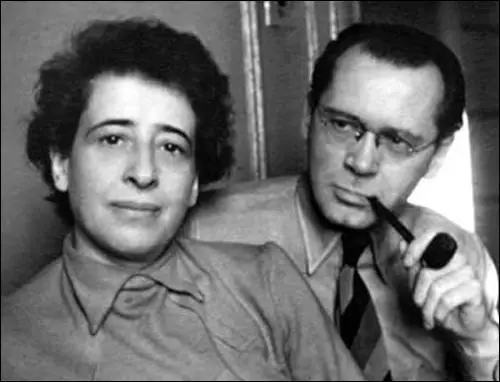

In 1936, Günther Stern left for New York City and they were formally divorced in August 1937. Hannah Arendt never wrote much in direct, personal terms about her own experiences in Paris. However, she did write a great deal about what she called "Europe's greatest immigration-reception area". She wrote about the desperate feeling of the stateless person at having no rights at all, of being outside the pale of the law. (83)

Hannah Arendt fell in love with Heinrich Blücher in the spring of 1936. "Arendt was twenty-nine, Blücher thirty-seven... They fell in love almost at first sight. Both were still formally married but separated from their spouses.... Blücher came from a poor, non-Jewish Berlin working-class background. He was an autodidact who had gone to night school but never graduated... Their attraction was at once intellectual and erotic. Blücher was an autodidact but a highly learned one.... Arendt was fascinated by his intellect. Their relationship now ripened in an atmosphere of intense eroticism." (84)

Arendt's biographer, Daniel Maier-Katkin, has argued: "He (Blücher) was excitable and full of enthusiasms, but still the type who can keep his head when all about are losing theirs. If you were on a lifeboat in a storm in shark-infested water, Blücher would be the companion you would want to have. Tempest-tossed in a dangerous world, Hannah felt safe and secure with Blücher. It would be hard to imagine a steadier or more courageous man, or one more different than Martin Heidegger." (85)

Hannah found herself being able to speak to him about feelings and fears she had never been able to acknowledge before. She also found herself learning a great deal from him. "He had a sense of history and politics that went far beyond the concerns of her Zionist friends. Later she was to acknowledge with unreserved gratitude the enormous influence on her own political thinking of this clever, untutored German who had learned his politics the hard way. And he told his friends that he had at last found the person he needed." (86)

Hannah eventually agreed that she loved Blücher. "I can only truly exist in love. And that is why I was so frightened that I might simply get lost. And so I made myself independent. And about the love of others who branded me as coldhearted, I always thought: if you only knew how dangerous love would be for me. Then when I met you, suddenly I was no longer afraid... It still seems incredible to me that I managed to get both things, the 'love of my life' and a oneness with myself. And yet, I only got the one thing when I got the other. But finally I also know what happiness is." (87)

Blücher was a former member of the Spartacus League and the German Communist Party (KPD). He had taken part in the failed German Revolution and saw its leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht murdered with the tacit approval of Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the President of Germany. He became disillusioned with the rule of Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union and in 1928 left the KPD. (88)

Dwight Macdonald would later describe Blücher's political identity as a "true, hopeless anarchist." Blücher remained friends with left-wing radicals but became increasingly preoccupied with the arts. Blücher became a close friends with Robert Gilbert, a Jewish artist (real name Robert Winterfeld) had fled from Nazi Germany in 1933. Gilbert, a left-wing songwriter, filmmaker, social critic and entertainer, introduced Blücher to Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht. (89)

In September, 1939, Blücher and all male German immigrants in France were deemed potential dangers to French security and were interred in camps in the provinces. He wrote to Arendt that: "As you can imagine, there are quite a few people here who think of nothing but their own personal destiny." However, because he had a loving partner he was able to cope with being in an internment camp: "I love you with all my heart... My beauty, what a gift of happiness it is to have this feeling, and to know that it will last a whole lifetime and will not change except to grow stronger." (90)

Blücher was eventually released and the couple married on 16th January, 1940. At the beginning of May, with the French government expecting a German invasion, ordered that all Germans except the old, the young, and mothers of children report as enemy aliens to internment camps, the men at Stadion Buffalo and the women at the Velodrome d'Hiver. Arendt observed: "Contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings - the kind that are put into concentration camps by their foes and in internment camps by their friends." (91)

The German Army invaded on 10th May, 1940, Arendt rightly predicted would soon be turned over to the Germans. She therefore decided to escape from the camp. Those that remained were later deported to Auschwitz. She walked for over 200 miles to Montauban, a meeting point for escapees. Blücher also escaped from his camp during a German air-raid. They were hidden by the parents of Daniel Cohn-Bendit until friends in United States managed to obtain emergency visas for the couple. (92)

Bernard Lazare and Zionism

Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher arrived in New York City by boat from Lisbon in May 1941. A refugee organization arranged for her to spend two months with an American family in Massachusetts. "The couple who took her in were very high-minded and puritanical; the wife allowed no smoking or drinking in the house... Yet Hannah was impressed by the couple, especially their intense feeling for the democratic political rights and responsibilities of American citizens" (93)

Her first task was to learn English. Within a year it was good enough to become a part-time lecturer in European history at Brooklyn College. She also wrote a biweekly column in the German language newspaper, Aufbau (other contributors included Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig). Blücher worked for a while shoveling chemicals in a New Jersey factory, and then as a research assistant for the Committee for National Morale, an organization whose goal was at first to encourage the United States to enter the Second World War. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor it became an openly anti-fascist group. (94)

Arendt became interested in the political career of Bernard Lazare, the a French literary critic and political journalist. became friends with Theodore Herzl, the founder and leader of the Zionist movement. (95) He became a leading supporter of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer of the French General Staff, who was accused and convicted of espionage for Germany. He argued that Dreyfus was innocent and had been convicted as part of an anti-Semitism campaign. In the first pamphlet on the case, Lazare revealed the illegality of the trial and refuted the accusation point by point and demanded the sentence be overturned. The pamphlet was sent to 3,500 public figures. (96)

Lazare did not get enough support from Zionists and in a article, Job's Dungheap: Essays on Jewish Nationalism and Social Revolution, published after his death, he attacked wealthy Jews in France for not giving enough support for recently arrived Jewish immigrants: "It isn't enough for them to reject any solidarity with their foreign-born brethren; they have also to go charging them with all the evils which their own cowardice engenders. They are not content with more jingoist than the native Frenchmen; like all emancipated Jews everywhere, they have also of their own volition broken all ties of solidarity. Indeed, they go far that for the three dozen or so men in France who are ready to defend one of their martyred brethren you can find some thousands ready to stand guard over Devil's Island, alongside the most rabid patriots of the country." (97)

In an article published in 1942, Arendt wrote about the conflict between Theodore Herzl and Bernard Lazare. She pointed out that Lazare had been hostile to the Jewish leadership and eventually withdrew from the Zionist movement because he found it patronizing towards ordinary Jews, who were excluded from the councils of policy. Arendt agreed with Lazare that anti-Semitism as an isolated example of hatred of one people, but as part of a broader pattern of racial and ethnic hatred associated with a larger collapse of moral values in Europe. Arendt also agreed with Lazare about the Zionists approach to the poor. (98)

Arendt believed if there is a divide in the world at all, it was not between one ethnic or national group and one another, but between people who are drawn to diversity and people who are repulsed by it. "Herzl had hoped for the support of anti-Semites who, wanting an ethnic cleansing of Europe, would help Jews make their way to Palestine. Arendt, on the other hand, like Lazare, who thought the core of the matter was that the Jews were poor, downtrodden, and demoralized, hoped to find real allies among all oppressed groups to oppose every form of racism, fascism, and imperialism. (99)

Lazare felt that wealthy Jews, who were excluded from the councils of policy. He felt that wealthy Jews offered charity in exchange for political control of the community, and that this meant that poor Jews, the bulk of the people, were oppressed from within as well as without: "I want no longer to have against me not only the wealthy of my people who exploit me and sell me, but also the rich and poor of other peoples who oppress and torture me in the name of my rich." (100)

The Holocaust

Hannah Arendt first heard about the extermination of the Jews in Europe in 1943: "We didn't believe this because militarily it was unnecessary and uncalled for. My husband is a former military historian; he understands something about these matters. He said don't be gullible; don't take these stories at face value. They can't go that far! And then a half year we believed it after all, because we had proof... It was really as if an abyss had opened... This ought not to have happened. And I don't mean just the number of victims. I mean the method, the fabrication of corpses and so on - I don't need to go into that. This should not have happened. Something happened there to which we cannot reconcile ourselves. None of us ever can." (101)

However, she explained that if one took seriously what Adolf Hitler had said before the outbreak of the Second World War, the Holocaust could have been predicted. Arendt quoted Hitler as making an announcement to the Reichstag in January, 1939: "I want today once again to make a prophecy: In case the Jewish financiers... succeed once more in hurling the peoples into a world war, the result will be... the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe." (102) Arendt adds that "translated into non-totalitarian language, this meant: I intend to make war and I intend to kill the Jews of Europe." (103)

In 1946, Karl Jaspers sent Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher a copy of his book The Question of German Guilt. Blücher was not impressed: "A Christianized/pietistic/hypocritical nationalizing piece of twaddle... allowing Germans to continue occupying themselves exclusively with themselves for the noble purpose of self-illumination... serving the purpose of extirpating responsibility... This has always been the function of guilt, beginning with original sin... Jasper's whole ethical purification-babble leads him to solidarity with the German National Community and even with the National Socialists, instead of solidarity with those who have been degraded. It seems that... he wishes to redeem the German people.... The Germans don't have to deliver themselves from guilt, but from disgrace. I don't give a damn if they'll roast in hell someday or not, as long as they're prepared to do something to dry the tears of the degraded and the humiliated... Then we could at least say that they have accepted the responsibility and made good, may the Lord spare their souls." (104)

Arendt told Jaspers that he had overlooked the fact that taking responsibility consists of more than accepting defeat and its consequences, or spiritual purification; the highest priority was not introspection, but action on behalf of victims. "We understand very well that you want to leave here and go to Palestine, but, quite apart from that, you should know that you have every right of citizenship here, that you can count on our total support and that mindful of what Germans have inflicted on the Jewish people, we will, in a future German republic, constitutionally renounce anti-Semitism."

She added: "The Nazi crimes, it seems to me, explode the limits of the law; and that is precisely what constitutes their monstrousness. For these crimes, no punishment is severe enough. It may well be essential to hang Göring, but it is totally inadequate. This is, this guilt, in contrast to all criminal guilt, oversteps and shatters any and all legal systems... I don't know how we will ever get out of it, for the Germans are now burdened with thousands or tens of thousands of people who cannot be adequately punished within the legal system; and we Jews are burdened with millions of innocents, by reason of which every Jew alive today can see himself as innocence personified." (105)

Israel and Zionism

In October 1944, the Zionist Organization of America, the largest and most influential section of the World Zionist Organization, partially in outrage over what had been done to European Jewry and partially in recognition of worldwide shock and sympathy, adopted a resolution calling for a "free and democratic Jewish commonwealth to embrace the whole of Palestine, undivided and undiminished". Arendt complained that there was no mention of the Arabs already living on the land, not even a guarantee that they would receive assurances of minority rights. (106)

Hannah Arendt objected to the "ancient idea of a chosen people with a promised land as a justification for the resolution of conflicts not on the basis of politics, but of theological assertions about claims of God-given superiority, which she saw as a form of racism". She rejected the idea of Theodore Herzl of transporting "the people without a country to the country without a people" on the basis that the million or so Palestinian Arabs were people and that it did not matter whether they were formally constituted as a people in a nation or state. (107)

Arendt predicted that if a Jewish state was to be successful it would need the support of one of the major powers: "The Zionists, if they continue to ignore the Mediterranean peoples and watch out only for the big far away powers, will appear as their tools, the agents of foreign and hostile interests. Jews who know their own history should be aware that such a state of affairs will inevitably lead to a new wave of Jew-hatred; the anti-Semitism of tomorrow will assert that Jews not only profiteered from the presence of foreign big powers in the region but had actually plotted it and hence are guilty of the consequences." (108)

At the end of the Second World War the British government found itself in intense conflict with the Jewish community over Jewish immigration limits into Palestine. At the same time, hundreds of thousands of Jewish Holocaust survivors and refugees sought a new life far from their destroyed communities in Europe. Jewish organizations attempted to bring these refugees to Palestine but many were turned away or rounded up and placed in detention camps because of pressure from Arabs living in the territory. (109)

On 22 July 1946, Irgun attacked the British administrative headquarters for Palestine, which was housed in the southern wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. A total of 91 people of were killed (41 Arabs, 28 British citizens, 17 Palestinian Jews, 2 Armenians, 1 Russian, 1 Greek and 1 Egyptian) and 46 were injured. The attack initially had the approval of the Haganah, the main paramilitary organization of the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine. It was claimed the bombing was in response to a series of widespread raids conducted by the British authorities. It has been claimed by Bruce Hoffman, the author of Inside Terrorism (1999) that it was one of the "most lethal terrorist incidents of the twentieth century." (110)

The Jewish insurgency continued and after three Irgun fighters had been sentenced to death for terrorist activities, two British sergeants were captured, held hostage, and it was claimed they would be killed if their men were executed. When the British carried out the executions, the Irgun responded by killing the two hostages and hanging their bodies from eucalyptus trees, booby-trapping one of them with a mine which injured a British officer as he cut the body down. The hangings caused widespread outrage in Britain and were a major factor in the consensus forming in Britain that it was time to evacuate Palestine. (111)

Hannah Arendt condemned the Palestine terrorists, and their ambition to extend future Jewish territory east of the River Jordon. "It was the same kind of Jewish nationalism, with the same disregard for Arab rights, that she had dissociated herself from in Germany in the 1930s - and she did not hesitate to call the terrorists and those who supported them 'Jewish Fascists'.... While American Zionists... were calling for the British to hand Palestine completely over to the Jews, she was developing the argument that Palestine should be a nation in which Jews and Arabs were equal citizens, and should become a member of the kind of British Commonwealth which seemed to her likely to develop after the war, with India a similar kind of dominion member." (112)

In September 1947, the British cabinet decided to evacuate Palestine. According to Colonial Secretary Arthur Creech Jones, four major factors led to the decision to evacuate Palestine: the inflexibility of Jewish and Arab negotiators who were unwilling to compromise on their core positions over the question of a Jewish state in Palestine, the economic pressure that stationing a large garrison in Palestine to deal with the Jewish insurgency and the possibility of a wider Jewish rebellion and the possibility of an Arab rebellion put on a British economy already strained by the Second World War. (113)

On 14th May 1948, the day before the expiration of the British Mandate, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, declared "the establishment of a Jewish state" to be known as Israel. The following day, the armies of four Arab countries - Egypt, Syria, Transjordan and Iraq, launched the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Soon afterwards Yemen, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Sudan joined the war. The purpose of the invasion was to prevent the establishment of the Jewish state at inception, and some of the Arab leaders talked about driving the Jews into the sea. (114)

In an article written in May 1948, Arendt argued that Israel's early victories demonstrated military superiority; but time and numbers, she cautioned were inevitably against the Jews. It was possible to win many battles and still lose the war: "The victorious Jews would live surrounded by an entirely hostile Arab population, secluded inside ever-threatened borders, absorbed with physical self-defense to a degree that would submerge all other interests and activities... The nation no matter how many immigrants it could still absorb and how far it extended its boundaries... would still remain a very small people greatly outnumbered by hostile neighbors." (115)

In 1949, Israel signed separate armistices with Egypt on 24th February, Lebanon on 23rd March, Transjordan on 3rd April, and Syria on 20th July. Israel controlled territories of about one-third more than was allocated to the Jewish State under the UN partition proposal. After the armistices, Israel had control over 78% of the territory comprising former Mandatory Palestine. Arendt commented "like virtually all other events of our century, the solution of the Jewish question merely produced a new category of refugees, the Arabs, thereby increasing the number of the stateless and rightless by another 700,000 to 800,000 people." (116)

Existentialism

In 1946 Hannah Arendt wrote an essay on the development of existentialism, beginning with Søren Kierkegaard and including the work of Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers, John-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. She explained how Kierkegaard's point of departure is the individual's sense of subjectivity and of being lost and alone in a world in which nothing is certain but death: "Death is the event in which I am definitely alone, an individual cut off from everyday life. Thinking about death becomes an 'act' because in it man makes himself subjective and separates himself from the world and everyday life with other men... On this premise rests not only the modern preoccupation with the inner life but also fanatical determination, which also begins with Kierkegaard, to take the moment seriously, for it is the moment alone that guarantees existence." (117)

In Being and Time (1927) Heidegger spells out our "average everyday" attitude towards death. The first thing that he emphasizes is that, although we all know, in one sense, that we are going to die, there is another sense in which we are not fully aware of that fact. (118) As Heidegger points out, "death is understood as an indefinite something which, above all, must arrive from somewhere or other, but which is proximally not yet present-at-hand for oneself, and is therefore no threat." (119)

Arendt argued that Jaspers had used the fact of death as a starting point for a life-affirming philosophy in which man's existence is not simply a matter of Being, but rather a form of human freedom. For Jaspers "man achieves reality only to the extent that he acts out of his own freedom rooted in spontaneity and "connects through communication with the freedom of others." She compared Jaspers with Heidegger, who interpreted death as proof of man's "nothingness". She suggests that this approach to philosophy is connected to his support for Adolf Hitler. (120)

In another article published in September, 1946, she attacked German intellectuals such as Heidegger, who went out of the way to aid the Nazis. This included the concentration camps and the extermination camps: "Last came the death factories - and they all died together, the young and the old, the weak and the strong, the sick and the healthy; not as people, not as men and women, children and adults, boys and girls, not as good and bad, beautiful and ugly - but brought down to the lowest common denominator of organic life itself." She went on to say: "Heidegger "whose enthusiasm for the Third Reich was matched only by his glaring ignorance of what he was talking about." (121)

In 1948 Hannah Arendt spent two months in New Hampshire. While she was away Heinrich Blücher began an affair with "a vivacious and sensuous young Jewess of Russian descent". Hannah was very unhappy that the affair was known to some of their friends and felt publicly humiliated. However she was "a Weimar Berliner in social mores, she did not define faithfulness narrowly, maritally". Arendt later wrote: "To be sure, in this world there is no eternal love, or ordinary faithfulness. There is nothing but the intensity of the moment, that is, passion, which is even a bit more perishable than man himself." . (122)

During this period she formed a close friendship with Hilde Frankel, the secretary and adored mistress of the theologian Paul Tillich. Hannah described Frankel as "gifted with erotic genius" and with her enjoyed an intimacy "like none she had ever known with a woman". In a letter she wrote to Frankel she expressed her gratitude for the relationship: "Not only for the relaxation which comes from an intimacy like none I have ever known with a woman, but also for the unforgettable good fortune of our nearness, a good fortune of our nearness, a good fortune which is all the greater because you are not an intellectual (a hateful word) and therefore are a confirmation of my very self and of my true beliefs." (123)

The Origins of Totalitarianism

In 1951 Hannah Arendt published her major work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, a "grand synthesis of a decade of thinking about the destruction of the world and civilization into which she had been born". It was dedicated to Heinrich Blücher, who had been her principal thinking partner in this effort, and assisted with the research. Raymond Aron was impressed "by the strength and subtlety of its analyses" and helped establish her prominence as a political thinker and public intellectual. The review in the New York Times said it was "the work of one who has thought as well as suffered". (124)

The book was over a quarter of a million words. In the first two sections of her book, Anti-Semitism and Imperialism, Arendt ranges far and wide through the history in the last 200 to 300 years, identifying events that might be thought to have played that kind of part in the eventual emergence of totalitarianism (the subject of the third section). "Hannah Arendt sets the scene with the nation-states of Europe as they developed at the end of the feudal era. Here was a world of legitimate and limited conflicts: within each nation, conflicts between class and class and between party and party; in Europe as a whole, conflicts between one nation and another." (125)

In the introduction of the book, Hannah Arendt points out that their is a difference between Anti-Semitism and Jew-hatred: "Anti-Semitism, a secular nineteenth-century ideology - which in name, though not in argument, was unknown before the 1870's - and religious Jew-hatred, inspired by the mutually hostile antagonism of two conflicting creeds, are obviously not the same; and even the extent to which the former derives its arguments and emotional appeal from the latter is open to question. The notion of an unbroken continuity of persecutions, expulsions, and massacres from the end of the Roman Empire to the Middle Ages, the modern era, and down to our own time, frequently embellished by the idea that modern Anti-Semitism is no more than a secularized version of popular medieval superstitions, is no less fallacious than the corresponding anti-semitic notion of a Jewish secret society that has ruled, or aspired to rule, the world since antiquity." (126)

Arendt argues that there were several reasons why Anti-Semitism became an important force in the 19th century. "Of all European peoples, the Jews had been the only one without a state of their own and had been, precisely for this reason, so eager and so suitable for alliances with governments and states as such, no matter what these governments or states might represent. On the other hand, the Jews had no political tradition or experience, and were as little aware of the tension between society and state as they were on the obvious risks and power-possibilities of their new role." (127)

Arendt used the example of the S M von Rothschild, a banking enterprise established in 1820 by Amschel Mayer Rothschild in Frankfurt. Branches were established by Salomon Mayer Rothschild (Vienna), Nathan Mayer Rothschild (London), Calmann Mayer Rothschild (Naples) and Jakob Mayer Rothschild (Paris). According to Niall Ferguson, the author, The House of Rothschild (1999), during the 19th century, the Rothschild family possessed the largest private fortune in the world, as well as in modern world history. (128)

Arendt explained: "The history of the relationship between Jews and governments is rich in examples of how quickly Jewish bankers switched their allegiance from one government to the next even after revolutionary changes. It took the French Rothschilds in 1848 hardly twenty-four hours to transfer their services from the government of Louis Philippe to the new short-lived French Republic and again to Napoleon III. The same process repeated itself, at a slightly slower pace, after the downfall of the Second Empire and the establishment of the Third Republic." (129)

Arendt gives the example of Karl Lueger, the leader of the Christian Social Party (CSP) and the mayor of Vienna. Lueger criticised the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) in Austria, the largest political party. Its leader was Victor Adler, and Lueger attacked him for his Jewish origins and his Marxism. Lueger advocated an early form of "fascism". This included a radical German nationalism (meaning the primacy and superiority of all things German), social reform, anti-socialism and anti-semitism. In one speech Lueger commented that the "Jewish problem" would be solved, and a service to the world achieved, if all Jews were placed on a large ship to be sunk on the high seas. (130)

These speeches by Lueger upset Franz Joseph, the Emperor of the Austria–Hungary Empire, who in 1867 had granted the Jewish population equal rights, saying "the civil rights and the country's policy is not contingent in the people's religion". The persecution of Jews under Tsar Alexander III resulted in large-scale emigration from Russia and by 1890 over 100,000 Jews lived in Vienna. This amounted to 12.1% of the total population of the city. Migration from Russia grew even faster after the forced expulsion of Jews from Moscow in 1891. (131)

After the 1895 elections for the Vienna's City Council the Christian Social Party, with the support of the Catholic Church, won two thirds of the seats. Lueger was selected to became mayor of Vienna but this was overruled by Emperor Franz Joseph who disliked his anti-semitism. The Christian Social Party retained a large majority in the council, and re-elected Lueger as mayor three more times, only to have Franz Joseph refuse to confirm him each time. He was elected mayor for a fifth time in 1897, and after the personal intercession by Pope Leo XIII, his election was finally sanctioned later that year. Konrad Heiden has pointed out that without the "all-powerful Catholic Church" Lueger could never have achieved power." (132)

Controversially, Arendt refused to exempt the Jews in Europe from political responsibility for what happened in Nazi Germany: "She rejected the idea that eternal anti-Semitism was simply a fact of history, and argued that a degree of responsibility for the persistence of anti-Semitism lies with the leaders of Jewish communities - the privileged parvenus with wealth and access to power who had governed their impoverished brethren through economic power and philanthropy, consistently aligning themselves with the wrong and ultimately losing side in national and European politics. They preferred monarchies to republics because they instinctively mistrusted the mob. They did not understand, Arendt argued, that over time, as various classes of society came into conflict with the state, ordinary people became anti-Semitic because the Jewish leadership invariably aligned their communities with whoever was in power. She did not offer this as a justification for what happened, but as part of an effort to understand how it could have happened." (133)

The book included a critique of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin and the totalitarian political system they had established. The term "totalitario" was coined by Giovanni Gentile, the Italian political theorist who had helped establish the corporate state under Benito Mussolini in the 1920s. He used the word to refer to the totalizing structure, goals, and ideology of a state directed at the mobilization of entire populations and control of all aspects of social life including business, labour, religion and politics. (134)

Arendt suggests that totalitarian dictators need to develop a special relationship with the masses. Hitler, for example, exercised a "magic spell" over his listeners. This fascination, what the German historian, Gerhard Ritter, has described as "the strange magnetism that radiated from Hitler in such a compelling manner" rested "on the fanatical belief of this man in himself." She adds: "The hair-raising arbitrariness of such fanaticism holds great fascination for society because for the duration of the social gathering it is freed from the chaos of opinions that it constantly generates." (135)

Fascist dictators aim and succeed in organizing masses, not classes. "Totalitarian movements are possible wherever there are masses who for one reason or another have acquired the appetite for political organization. Masses are not held together by a consciousness of common interest and they lack that specific class articulateness which is expressed in determined, limited, and obtainable goals. The term masses applies only where we deal with people who either because of sheer numbers, or indifference, or a combination of both, cannot be integrated into any organization based on common interest, into political parties or municipal governments or professional organizations or trade unions. Potentially, they exist in every country and form the majority of those large numbers of neutral, politically indifferent people who never join a party and hardly ever go to the polls." (136)

Ardent pointed out that it was characteristic of the rise of the Nazi movement in Germany "that they recruited their members from this mass of apparently indifferent people whom all other parties had given up as too apathetic or too stupid for their attention. The result was that the majority of their membership consisted of people who never before had appeared on the political scene. This permitted the introduction of entirely new methods into political propaganda, and indifference to the arguments of political opponents; these movements not only placed themselves outside and against the party system as a whole, they found a membership that had never been reached, never been 'spoiled' by the party system. Therefore they did not need to refute opposing arguments and consistently preferred methods which ended in death rather than persuasion, which spelled terror rather than conviction." (137)