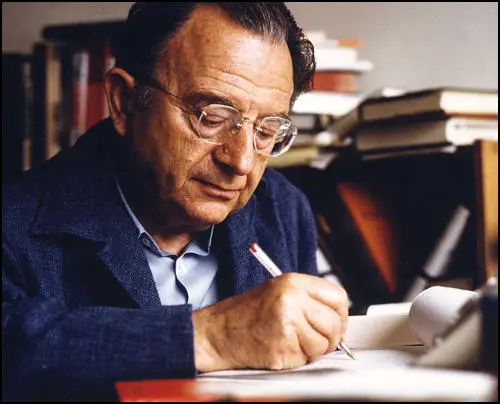

Erich Fromm

Erich Fromm, the son of Rosa Krause Fromm and Naphtali Fromm, was born in Frankfurt, Germany on 23rd March, 1900. Both his parents were orthodox Jews. Erich was the couple's only child. It was not a happy marriage and he later described his father as distant and his mother as overprotective. (1)

Fromm's great-uncle, Ludwig Krause, was a prominent Talmudic scholar and a great influence on his life. "Erich became fascinated with the Hebrew Bible, especially with the prophetic writings of Isiah, Amos, and Hosea and their visions of peace and harmony among nations." (2)

For a long time Erich Fromm hoped to make the study of the Talmud his life's work. However, "for Fromm, the main point was, perhaps, not what he studied, but rather the values attached to studying and the different way of life that marks it out." (3) Fromm was given an intense religious education from noted scholars and friends of the family, and groomed from an early age to carry on family tradition and became a scholar of the Talmud." (4)

In 1912 Naphtali Fromm employed Oswald Sussman, a young Galacian Jew, to help him with his wine business. Sussman lived in the Fromm household for two years and during this period he took an interest in Erich's education. This included visits to Frankfurt Museum. Sussman was a socialist and introduced him to the writings of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels and engaged him in serious discussions about politics. Fromm later recalled that Sussman "was an extremely honest man, courageous, a man of great integrity. I owe a great deal to him." (5)

Fromm adopted Sussman as a father figure. He later claimed that Sussman was the first adult to take a real interest in him as an individual. Fromm did not enjoy a good relationship with his father who he believed was "very neurotic" and "obsessive". Fromm claimed that he "suffered under the influence of a pathologically anxious father who overwhelmed me with his anxiety, at the same time not giving me any guidelines and having no positive influence on my education." (6)

Erich Fromm and the First World War

Erich was 14-years-old and a student at Frankfurt's Wohler Gymnasium, when the First World War broke out. His Latin teacher, who had previously argued that the German arms build-up would keep the peace was jubilant: "From then on, I found it difficult to believe in the principle that armament preserved peace." Fromm was shocked by how overnight his teachers and fellow students became "fanatical nationalists and reactionaries" attributing the war to British aggression. Only his English teacher proclaimed a different message and warned against a quick military victory pointing out that "so far England has never lost a war." (7)

Erich Fromm described the war as "the most crucial experience in my life." Following the example of his English teacher, he came to resist the simplistic portrayal of an innocent Germany being attacked by a bellicose Britain. Some of his uncles and cousins were killed during the war. Some of his uncles and cousins were killed during the war. Oswald Sussman also lost his life in the conflict. "When the war ended in 1918, I was a deeply troubled young man who was obsessed by the question of how war was possible, by the wish to understand the irrationality of human mass behavior, by a passionate desire for peace and international understanding." (8)

Political Development

In 1918 Fromm attended the University of Frankfurt am Main where he took courses in medieval German history, the theory of Marxism, social movements, and the history of psychology. Fromm also came under the influence of the writings of Hermann Cohen, the celebrated neo-Kantian philosopher and biblical scholar, who was a liberal in terms of religious observance and biblical exegesis but espoused a variety of socialist humanism similar to that of Moses Hess, the left-wing Hegelian who had converted Frederick Engels, and Karl Marx, to socialism in 1840. Cohen was also a strong opponent of Jewish nationalism.

The following year he moved to the University of Heidelberg, where he began studying philosophy and sociology under Alfred Weber, Karl Jaspers, and Heinrich Rickert. In 1922 Fromm obtained a doctorate in sociology under the supervision of Weber with a dissertation on three Jewish communities in Germany. According to Daniel Burston, the author of The Legacy of Erich Fromm (1991): "Neither Rickert nor Jaspers seem to have much effect on Fromm; their ideas are not mentioned anywhere in his published work in the form of either defense or critique." (9)

Fromm became a devotee of Rabbi Nehemiah Nobel, a brilliant, charismatic teacher who combined classical religious instruction with a mysticism, philosophy, socialist and psychoanalysis. Fromm, along with other Nobel followers, joined Martin Buber and Gershom Scholem, as teachers in the Free Jewish Study House, the pioneering centre for adult education established by Franz Rosenzweig. (10)

Erich Fromm met Karen Horney, a senior figure at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute. Although there was a fifteen year age difference, they both felt a mutual sexual attraction. "Fromm... showed maverick, iconoclastic tendencies in his leftist views, rebelling against the social status quo. It may have been this quality, of which Karen had her share, that attracted her, or his ability to encompass his contradictory inner drives. Indeed his attempt to reconcile opposites was one hallmark of his theories, for instance the contradictions between inner psychic and external social forces, between psychoanalysis and Marxism.... As for him, he could well have experienced her in the same way other students in his class did: She represented a caring, understanding, yet at the same time strong mother figure." (11)

After the war Fromm began a relationship with Goldie Ginsburg (who later married his friend, Leo Löwenthal). During their time together Goldie introduced him to Frieda Reichmann, a doctor who was eleven years his senior. During the war she had run a clinic for brain-injured German soldiers. Her work led to a better understanding of the physiology and pathology of brain functions. She also studied the work of Sigmund Freud at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute under Karl Abraham and Max Eitingon. (12)

In 1923 Fromm and Reichmann opened a therapeutic facility for Jewish patients in Heidelberg. The goal was to nurture simultaneously Jewish identity and psychic health along quasi-socialist lines. As Reichmann pointed out "we first analyze the people and second made them aware of their tradition. As they were both socialists they "didn't want to go on only treating wealthy people." Patients paid what they could or donated their labour in exchange for treatment." (13)

Reichmann's biographer, Gail A Hornstein, believed that they made a good match: "Erich was the perfect choice for Frieda. He was charming and warm... Erich also needed to be taken care of, a quality Frieda always found reassuring (in other people)." The wedding took place on 14th May, 1926. "Frieda got a good bargain; she got a man with her father's charm but more brains, who respected her independence." (14) Reichmann later recalled: "We analyzed people as compensation for letting them work. I analyzed the housekeeper, I analyzed the cook. You may imagine what happened if they were in a phase of resistance! It was a wild affair... Erich and I had an affair. We weren't married and nobody was supposed to know about that and actually nobody did know." (15)

Social Psychology

In 1927 Erich Fromm commenced analytic training with Hanns Sachs and Theodor Reik. He also began associating with left-leaning therapists such as Ernst Simmel, Wilhelm Reich, Annie Reich, Helene Deutsch, Edith Jacobson, Edith Weigert and Otto Fenichel who began to take into consideration the social and political impact on the clinical situation. Together they explored ways of "finding a bridge between Marx and Freud". (16)

Simmel, the President of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute, took pride that the clinics free treatment did not differ in the least from that of patients paying high fees. "All patients are... entitled to as many weeks or months of analysis as his condition requires". In this way the Berlin Institute was fulfilling social obligations incurred by society, which "makes its poor become neurotic and, because of its cultural demands, lets its neurotics stay poor, abandoning them to their misery." (17)

In 1928 Frieda Fromm-Reichmann set up a private practice at 15 Mönchshofstraße in Berlin. She continued a close relationship with Georg Groddeck, who was director of the Marienhöhe Sanatorium in Baden-Baden. She saw him often and they corresponded regularly. She introduced him to her husband who became his patient: "When I think of all analysts in Germany I knew, he was, in my opinion, the only one with truth, originality, courage and extraordinary kindness. He penetrated the unconscious of his patient, and yet he never hurt. Even if I was never his student in any technical sense, his teaching influenced me more than that of other teachers I had." (18)

In 1929 Erich Fromm, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, Karl Landauer, Heinrich Meng, Georg Groddeck and Ernst Schneider, established the South German Institute for Psychoanalysis in Frankfurt. After completing his psychoanalytic training Fromm opened his own private practice in Berlin. (19)

Fromm became a patient of Groddeck. He later claimed that "many illnesses are the product of people's lifestyles. If one wants to heal them, one has to change a patient's way of life; only in very few cases can the illness be tackled through so-called specifica." In July 1931 he fell ill with tuberculosis and had to live a long time apart from Frieda. "Groddeck understood Fromm's illness as an expression of his wish to separate from his wife, at the same time showing his difficulty in coming to terms with this idea." (20)

Later that year Fromm published his first important article, Psychoanalysis and Sociology (1929) which provided an argument for the development of social psychology: "The application of psychoanalysis to sociology must definitely guard against the mistake of wanting to give psychoanalytic answers where economic, technical, or political facts provide the real and sufficient explanation of sociological questions. On the other hand, the psychoanalyst must emphasize that the subject of sociology, society, in reality consists of individuals, and that it is these human beings, rather than abstract society as such, whose actions, thoughts, and feelings are the object of sociological research." (21)

Fromm also gave a lecture in 1929 entitled The Application of Psycho-Analysis to Sociology and Religious Knowledge in which he outlined the basis for a rudimentary but far-reaching attempt at the integration of Freudian psychology and Marxist social theory. He decided to carry out a survey "to gain an insight into the psychic structure of manual and white-collar workers." A comprehensive questionnaire with 271 questions was designed a distributed to 3,300 recipients. By the end of 1931, Fromm and his assistant Hilde Weiss, received back 1,100 questionnaires for analysis. (22)

Fromm asked the workers who had the real power in the State today. More than half of the answers, 56%, claimed that it was the capitalists who had the real power in Germany: "According to Marxist theory and also according to the propaganda of the left-wing parties to which many respondents referred in their replies, the real source of power, even under a democratic constitution, lies in the economic sphere. It was not surprising, therefore, that suspicions about the workings of parliamentary democracy was constantly being voiced. Although the workers' parties formed the largest faction within the Reichstag, a strong sense of disillusionment prevailed in the working class as to its actual potential for power." (23)

The survey revealed that supporters of the Nazi Party had little sympathy for the plight of the poor or the unemployed. "The doctrine of the left-wing parties that the individual's fate is determined by his socio-economic situation was apparent in many of the answers... Significant differences between the various groups can be seen in the analysis of replies according to political orientation. Thus the majority (59%) of National Socialists believed, in significant contrast to the left-wing parties, in the self-responsibility of the individual, they usually further assumed that the unsuccessful had not used their innate capabilities and had failed to develop their character (47%). This attitude clearly shows the influence of National Socialist ideology, which stated that in the struggle for survival it is the strongest who wins out whilst the losers have revealed themselves as too weak." (24)

Fromm discovered that the right-wing nationalists tended to hold authoritarian attitudes that "seeks out and enjoys the subjugation of men under a higher external power, whether this power is the state or a leader, natural law, the past or God". Whereas those on the left tend to "demand a freedom which allows the individual to make his own happiness... this striving for freedom is to be made possible on the basis of solidarity with others". They also share a "hatred of all powers which restrict the freedom of the individual for purposes external to that individual as well as a sympathetic identification with all oppressed or weak people." (25)

In July, 1932, the Nazi Party won 230 seats in the Reichstag. It seemed only a matter of time before Adolf Hitler gained power. Erich Fromm, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, Wilhelm Reich, Ernst Simmel, Otto Fenichel, Franz Alexander and Sandor Rado decided to leave Germany. Karen Horney decided to follow the example of her Jewish friends and boarded a ship bound for the United States. At the International Psychoanalytical Association that year President Max Eitingon, pointed out: "We have... had to give up a large number of our most valued German colleagues to the American society." (26)

New York Psychoanalytic Institute

In 1933 Eric Fromm met Karen Horney when he visited Chicago. Horney had known Fromm and his wife, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann in Berlin, where all three had studied psycho-analysis. Fromm was now a divorced man and although he was fifteen years his junior, he began a sexual relationship with Horney. (27) "Over the next decade it is impossible to sort out Fromm's influences on Horney from her influences on him in the writing they each produced... It was during the Chicago years that Fromm and Horney's intellectual relationship deepened into a romantic one." (28)

The following year both Fromm and Horney moved to New York City. Fromm joined the faculty of the Institute for Social and Economic Research at Columbia University. Karen's friends claimed that although they did not live in the same house they spent a lot of time together. "Karen Horney's first two books, written during the early New York years, are laden with references to Fromm's works, published and unpublished. Some whispered that Horney was getting all her ideas from Fromm. The exchange, however, was anything but one-sided. The two were intertwined, emotionally and intellectually, in a relationship that must have fulfilled, perhaps for the first time in Horney's life, the dream of a marriage of minds, which she had envisioned in her letters to Oskar thirty years before." (29)

Horney and Fromm joined a small group of exiles who had fled from Nazi Germany. This included Erich Maria Remarque, Paul Tillich, Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer and Paul Kempner. Other close friends included Harold Lasswell, Karl Menninger and Harry Stack Sullivan. Hannah Tillich believed her husband were lovers. However, although she suffered terrible jealousy with some of her husband's liaisons, Hannah became very close to Karen: "She took me as a friend" and listened with "beautiful, but invisible, attention." Even though she was "gay with men, she'd never forget the woman". Hannah was very shy, and she was very grateful that Karen "would bring me out, get me to participate in the conversation." (30)

Horney began teaching at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute. She became close friends with Clara Thompson. "By temperament and personality, the two women were similar in some ways but quite different in others." One colleague who knew them both at this time commented that even though both had needs for leadership, domination and prestige, Karen "fascinated and at the same time frightened many of the students" whereas "Clara was more tender, encouraging and emotionally involved." (31)

In her work Horney stressed the importance of culture. As a woman she had long been conscious of its role in shaping our conceptions of gender. This view had been reinforced by her observation of the differences in culture between Europe and America. Horney was therefore receptive to the work of such sociologists, anthropologists, and culturally oriented psychoanalysts as Erich Fromm, Alfred Adler, Franz Boas, Margaret Mead, Max Horkheimer, Harry Stack Sullivan, John Dollard, Harold Lasswell and Ruth Benedict. (32)

Escape from Freedom (1941)

In 1941 Erich Fromm published Escape from Freedom. In the book he reveals the influence that Karl Marx has had on his thinking: "Modern European and American history is centred around the effort to gain freedom from the political, economic, and spiritual shackles that have bound men. The battles for freedom were fought by the oppressed, those who wanted new liberties, against those who had privileges to defend. While a class was fighting for its own liberation from domination, it believed itself to be fighting for human freedom as such and thus was able to appeal to an ideal, to the longing for freedom rooted in all who are oppressed.... Despite many reverses, freedom has won battles. Many died in those battles in the conviction that to die in the struggle against oppression was better than to live without freedom. Such a death was the utmost assertion of their individuality." (33)

Fromm argues that the First World War "was regarded by many as the final struggle and its conclusion the ultimate victory for freedom". Although Germany lost the war, its people saw the end of the monarchy and the establishment of the Weimar Republic as a move towards greater democracy. However, in some European countries, for example, Italy (1924), Portugal (1933), Germany (1934) and Spain (1939), established fascist dictatorships. "Only a few years elapsed (after the war) before new systems emerged which denied everything that men believed they had won in centuries of struggle. For the essence of these new systems, which effectively took command of man's entire social and personal life, was the submission of all but a handful of men to an authority over which they had no control." (34)

Fromm argued against the idea that that "the victory of the authoritarian system was due to the madness of a few individuals (Benito Mussolini, Antonio Salazar, Adolf Hitler, Francisco Franco) and that their madness would lead to their downfall in due time." Some people "believed that the Italian people, or the Germans, were lacking in a sufficiently long period of training in democracy, and that therefore one could wait complacently until they had reached the political maturity of the Western democracies". Fromm also rejected the idea "that men like Hitler had gained power over the vast apparatus of the state through nothing but cunning and trickery, that they and their satellites ruled merely by sheer force; that the whole population was only the will-less object of betrayal and terror." (35)

Fromm warned that democratic states were in danger of becoming fascist dictatorships and quotes John Dewey as saying: "The serious threat to our democracy is not the existence of foreign totalitarian states. It is the existence within our own personal attitudes and within our own institutions of conditions which have given a victory to external authority, discipline, uniformity and dependence upon The Leader in foreign countries. The battlefield is also accordingly here - within ourselves and our institutions." (36)

In the book Fromm explores the reasons why people in Germany supported Hitler. He points out that small businessmen were especially vulnerable to the appeal of fascism: "The small or middle-sized business man who is virtually threatened by the overwhelming power of superior capital may very well continue to make profits and to preserve his independence; but the threat hanging over his head has increased his insecurity and powerlessness far beyond what it used to be. In his fight against monopolistic competitors he is staked against giants, whereas he used to fight against equals. But the psychological situation of those independent business men for whom the development of modern industry has created new economic functions is also different from that of the old independent business men." (37)

Fromm suggests that in economically insecure time, some people are willing to give up their freedom. "The first mechanism of escape from freedom I am going to deal with is the tendency to give up the independence of one's own individual self and to fuse one's self with somebody or something outside oneself in order to acquire the strength which the individual self is lacking... The more distinct forms of this mechanism are to be found in the striving for submission and domination, or, as we would rather put it, in the masochistic and sadistic strivings as they exist in varying degrees in normal and neurotic persons respectively." (38)

According to Fromm, fascist dictators are popular with the authoritarian personality: "The authoritarian character wins his strength to act through his leaning on superior power. This power is never assailable or changeable. For him lack of power is always an unmistakable sign of guilt and inferiority, and if the authority in which he believes shows signs of weakness, his love and respect change into contempt and hatred.... The courage of the authoritarian character is essentially a courage to suffer what fate or its personal representative or 'leader' may have destined him for. To suffer without complaining is his highest virtue - not the courage of trying to end suffering or at least to diminish it. Not to change fate, but to submit to it, is the heroism of the authoritarian character. He has belief in authority as long as it is strong and commanding." (39)

Fromm argues that "Nazism is a psychological problem, but the psychological factors themselves have to be understood as being moulded by socio-economic factors; Nazism is an economic and political problem, but the hold it has over a whole people has to be understood on psychological grounds... In considering the psychological basis for the success of Nazism this differentiation has to be made at the outset: one part of the population bowed to the Nazi regime without any strong resistance, but also without becoming admirers of the Nazi ideology and political practice. Another part was deeply attracted to the new ideology and fanatically attached to those who proclaimed it. The first group consisted mainly of the working class and the liberal and Catholic bourgeoisie. In spite of an excellent organization, especially among the working class, these groups, although continuously hostile to Nazism from its beginning up to 1933, did not show the inner resistance one might have expected as the outcome of their political convictions. Their wish to resist collapsed quickly and since then they have caused little difficulty for the regime (excepting, of course, the small minority which has fought heroically against Nazism during all these years)." (40)

Fromm believed that the failure of the German Revolution at the end of the First World War had a damaging impact on the political consciousness of the workers. Especially as it was the Social Democratic Party government of Friedrich Ebert, that put down the German Communist Party led revolution. This made it very difficult for the left to unite against the growth of fascism and nationalism. "Psychologically, this readiness to submit to the Nazi regime seems to be due mainly to a state of inner tiredness and resignation… is characteristic of the individual in the present era even in democratic countries. In Germany one additional condition was present as far as the working class was concerned: the defeat it suffered after the first victories in the revolution of 1918. The working class had entered the post-war period with strong hopes for the realization of socialism or at least for a definite rise in its political, economic, and social position; but, whatever the reasons, it had witnessed an unbroken succession of defeats, which brought about the complete disappointment of all its hopes. By the beginning of 1930 the fruits of its initial victories were almost completely destroyed and the result was a deep feeling of resignation, of disbelief in their leaders, of doubt about the value of any kind of political organization and political activity. They still remained members of their respective parties and, consciously, continued to believe in their political doctrines; but deep within themselves many had given up any hope in the effectiveness of political action." (41)

Escape from Freedom from sold more than five million copies in twenty-eight different languages during the Second World War. As Lawrence J. Friedman, the author of The Lives of Erich Fromm: Love's Prophet (2014) has pointed out that the book becomes very popular every time democracy seems to be at risk in the world: "Since the Hungarian revolt of 1956, it has been surprisingly good sales wherever dictatorial regimes have been challenged." (42)

Karen Horney and Erich Fromm

Erich Fromm had been romanatically involved with Karen Horney since 1933. However, conflicts began to appear during the early days of the American Institute for Psychoanalysis. Fromm and Clara Thompson were angered that most of the new students were taken into analysis by Horney. According to several students at the institute Horney appeared to resent Fromm's popularity with students. Ruth Moulton has suggested that Fromm's first book in English, Escape from Freedom (1941) may have aroused Horney's jealously, particularly since he drew praise and attention from the same lay audience that admired Horney's work. Fromm was also the only teacher on the faculty who had Horney's kind of charisma. (43)

Horney's relationship with Fromm had been in difficulty for several years. Horney told her secretary, Marie Levy, that Fromm was a "Peer Gynt type". (44) In one of her books Horney explained what she meant by describing someone as Peer Gynt: "To thyself be enough... Provided emotional distance is sufficiently guaranteed, he may be able to preserve a considerable measure of enduring loyalty. He may be capable of having intense short-lived relationships, relationships in which he appears and vanishes. They are brittle, and any number of factors may hasten his withdrawal... As for sexual relations... he will enjoy them if they are transitory and do not interfere with his life. They should be confined, as it were, to the compartment set aside for such affairs." (45)

One of Horney's biographers has speculated: "Horney's version of Peer Gynt/Erich Fromm suggests that the relationship with Fromm may have ended because she wanted more from him than he was willing to give. "Might she have suggested marriage, for instance, and scared him off? On the other hand, however, Fromm couldn't have been entirely averse to marriage, since he married twice after his relationship with Horney ended. Perhaps, since both his subsequent marriages were to younger women, he was looking for a less powerful partner. Horney was fifteen years older than he, had published more books, and was better known at the time.... It is also true that Horney herself possessed many of the attributes of the Peer Gynt type. Could her typing of Fromm have been a projection? Was it she, not he, who backed off when the relationship reached a certain level of intimacy?" (46)

Another source concerned Karen Horney's daughter, Marianne. At Horney's suggestion, her daughter entered into psychoanalysis with Fromm. Marianne later admitted that her relationship with Fromm changed her life. After two years of analysis, she became aware of the artificiality of her relationship with her mother. This was followed by a wish for closer relationships, and resulted in new friendships and meeting her future husband and embarking on a "rich, meaningful" life, including "two marvelous daughters." The analysis had not provided a "cure" but had "unblocked... the capacity for growth." Marianne believes that Fromm was able to help her not only because he had been a good friend of her mother's for many years, and knew her "erratic relatedness or unrelatedness to people." As a result, he was able to "affirm a reality which I had never been able to grasp." (47)

In April 1943, a group of students requested that Fromm teach a clinical course in the institute program. Horney rejected the idea and argued that allowing a non-physician to teach clinical courses would make it more difficult for their institute to be accepted as a training program within New York Medical College. At a vote in the faculty council, Horney's proposal was victorious. Fromm, who was working as a training analyst in the privacy of his office, where he was analyzing and supervising students, was officially deprived of training status. As a result, he resigned, along with Clara Thompson, Harry Stack Sullivan and Janet Rioch. (48)

A large number of students were upset by this dispute. Ralph Rosenberg wrote to Ruth Moulton: "We children should get together and spank our unruly parents for their childish behaviour. The students may hold the balance of power in the mess. Thompson expects to recruit enough students from our gang and other sources to start a third school... The faculty has little to gain by the split and its undivided loyalty. The faculty has little to gain by the split and its accompanying mud slinging. The students lose the services of outstanding teachers... We do not know the actual issues causing the split... I therefore suggest that the students invite the Fromm and Horney group to discuss their differences in the presence of the students." (49)

Fromm, Thompson, Sullivan and Rioch, along with eight others, including Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, established their own institution, the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis, and Psychology. (50) Horney was deeply hurt by this development and told a Ernest Schachtel, who took holidays with the couple in happier times, that she unwilling for their friendship to continue unless he stopped seeing Fromm. Schachtel refused: "I was surprised she would make such a condition. I continued to see him, because we were old friends... I think she was deeply hurt by Erich Fromm." (51)

Fromm was an active member of the Socialist Party of America and published several successful books including. Man for Himself (1947), Psychoanalysis and Religion (1951) and The Sane Society (1955). He was also an outspoken critic of McCarthyism, the Cold War, the Vietnam War and a supporter of the Civil Rights Movement. According to Daniel Burston, the author of The Legacy of Erich Fromm (1991): "Despite his outspoken opposition to the Cold War, nuclear arms, and the Vietnam War, there is no public record of Fromm having suffered from the kind of official harassment, persecution, and character assassination that became the commonplaces of other people's lives during the McCarthy era and its aftermath." (52).

Art of Loving (1956)

Erich Fromm published his most successful book, The Art of Loving in 1956. He attempts to explain why love is so important to the human race: "Man is gifted with reason; he is life being aware of itself; he has awareness of himself, of his fellow man, of his past, and of the possibilities of his future. This awareness of himself as a separate entity, the awareness of his own short life span, of the fact that without his will he is born and against his will he dies, that he will die before those whom he loves, or they before him, the awareness of his aloneness and separateness, of his helplessness before the forces of nature and of society, all this makes his separate, disunited existence an unbearable prison. He would become insane could he not liberate himself from this prison and reach out, unite himself in some form or other with men, with the world outside." (53)

Fromm argues that humans have needed to love each other from the beginning of time: "The unity achieved in productive work is not interpersonal; the unity achieved in orgiastic fusion is transitory; the unity achieved by conformity is only pseudo-unity. Hence, they are only partial answers to the problem of existence. The full answer lies in the achievement of interpersonal union, of fusion with another person, in love... This desire for interpersonal fusion is the most powerful striving in man. It is the most fundamental passion, it is the force which keeps the human race together, the clan, the family, society. The failure to achieve it means insanity or destruction - self-destruction or destruction of others. Without love, humanity could not exist for a day." (54)

According to Fromm we learn about love from our parents: "For most children before the age from eight and a half to ten, the problem is almost exclusively that of being loved - of being loved for what one is. The child up to this age does not yet love; he responds gratefully, joyfully to being loved. At this point of the child's development a new factor enters into the picture: that of a new feeling; of producing love by one's own activity. For the first time, the child thinks of giving something to mother (or to father), of producing something - a poem, a drawing, or whatever it may be. For the first time in the child's life the idea of love is transformed from being loved into loving: into creating love. It takes many years from this first beginning to the maturing of love. Eventually the child, who may now be an adolescent, has overcome his egocentricity; the other person is not any more primarily a means to the satisfaction of his own needs. The needs of the other person are as important as his own - in fact, they have become more important. To give has become more satisfactory, more joyous, than to receive; to love; more important even than being loved. By loving, he has left the prison cell of aloneness and isolation which was constituted by the state of narcissism and self-centredness. He feels a sense of new union, of sharing, of oneness." Infantile love follows the principle: "I love because I am loved." Mature love follows the principle: "I am loved because I love." Immature love says: "I love you because I need you." Mature love says: "I need you because I love you." (55)

Fromm claims that there are essential differences in quality between motherly and fatherly love. "Motherly love by its very nature is unconditional. Mother loves the newborn infant because it is her child, not because the child has fulfilled any specific condition, or lived up to any specific expectation.... Unconditional love corresponds to one of the deepest longings, not only of the child, but of every human being; on the other hand, to be loved because of one's merit, because one deserves it, always leaves doubt; maybe I did not please the person whom I want to love me, maybe this, or that - there is always a fear that love could disappear.... No wonder that we all cling to the longing for motherly love, as children and also as adults. Most children are lucky enough to receive motherly love... As adults the same longing is much more difficult to fulfil. In the most satisfactory development it remains a component of normal erotic love; often it finds expression in religious forms, more often in neurotic forms." (56)

The relationship to father is quite different. "Mother is the home we come from, she is nature, soil, the ocean; father does not represent any such natural home. He has little connection with the child in the first years of its life, and his importance for the child in this early period cannot be compared with that of mother. But while father does not represent the natural world, he represents the other pole of human existence; the world of thought, of man-made things, of law and order, of discipline, of travel and adventure. Father is the one who teaches the child, who shows him the road into the world." Fromm argues that fatherly love is conditional love. Its principle is "I love you because you fulfil my expectations, because you do your duty, because you are like me." (57)

Fromm insists that the parents should prepare them for independence: "Mother should have faith in life, hence not be over-anxious, and thus not infect the child with her anxiety. Part of her life should be the wish that the child become independent and eventually separate from her. Father's love should be guided by principles and expectations; it should be patient and tolerant, rather than threatening and authoritarian. It should give the growing child an increasing sense of competence and eventually permit him to become his own authority and to dispense with that of father." (58)

Fromm then goes on to discuss erotic love. "Brotherly love is love among equals; motherly love is love for the helpless. Different as they are from each other, they have in common that they are by their very nature not restricted to one person. If I love my brother, I love all my brothers; if I love my child, I love all my children; no, beyond that, I love all children, all that are in need of my help. In contrast to both types of love is erotic love; it is the craving for complete fusion, for union with one other person. It is by its very nature exclusive and not universal; it is also perhaps the most deceptive form of love there is.... it is often confused with the explosive experience of 'falling' in love, the sudden collapse of the barriers which existed until that moment between two strangers.... this experience of sudden intimacy is by its very nature short-lived. After the stranger has become an intimately known person there are no more barriers to be overcome, there is no more sudden closeness to be achieved. The 'loved' person becomes as well known as oneself. Or, perhaps I should better say as little known." (59)

Erich Fromm attempts to explain the importance of self-love: "Granted that love for oneself and for others in principle is conjunctive, how do we explain selfishness, which obviously excludes any genuine concern for others? The selfish person is interested only in himself, wants everything for himself, feels no pleasure in giving, but only in taking. The world outside is looked at only from the standpoint of what he can get out of it; he lacks interest in the needs of others, and respect for their dignity and integrity. He can see nothing but himself; he judges everyone and everything from its usefulness to him; he is basically unable to love.... The selfish person does not love himself too much but too little; in fact he hates himself. This lack of fondness and care for himself, which is only one expression of his lack of productiveness, leaves him empty and frustrated. He is necessarily unhappy and anxiously concerned to snatch from life the satisfactions which he blocks himself from attaining. He seems to care too much for himself, but actually he only makes an unsuccessful attempt to cover up and compensate for his failure to care for his real self. Freud holds that the selfish person is narcissistic, as if he had withdrawn his love from others and turned it towards his own person. It is true that selfish persons are incapable of loving others, but they are not capable of loving themselves either." (60)

Fromm stressed the importance of good communication in close relationships. "To be concentrated in relation to others means primarily to be able to listen. Most people listen to others, or even give advice, with out really listening. They do not take the other person's talk seriously, they do not take their own answers seriously either. As a result, the talk makes them tired. They are under the illusion that they would be even more tired if they listened with concentration. But the opposite is true. Any activity, if done in a concentrated fashion, makes one more awake (although afterwards natural and beneficial tiredness sets in), while every unconcentrated activity makes one sleepy - while at the same time it makes it difficult to fall asleep at the end of the day." (61)

Fromm believed strongly that to love someone deeply we need to be sensitive to the needs of others. "If we look at the situation of being sensitive to another human being, we find the most obvious example in the sensitiveness and responsiveness of a mother to her baby. She notices certain bodily changes, demands, anxieties, before they are overtly expressed. She wakes up because of her child's crying, where another and much louder sound would not waken her. All this means that she is sensitive to the manifestations of the child's life; she is not anxious or worried, but in a state of alert equilibrium, receptive to any significant communication coming from the child. In the same way one can be sensitive towards oneself. One is aware, for instance, of a sense of tiredness or depression, and instead of giving in to it and supporting it by depressive thoughts which are always at hand, one asks oneself what happened? Why am I depressed? The same is done by noticing when one is irritated or angry, or tending to daydreaming, or other escape activities. In each of these instances the important thing is to be aware of them, and not to rationalise them in-the thousand and one ways in which this can be done; furthermore, to be open to our own inner voice which will tell us - often rather immediately - why we are anxious, depressed, irritated." (62)

Fromm believes that for society to function well, we need to express brotherly love. "The most fundamental kind of love, which underlies all types of love, is brotherly love. By this I mean the sense of responsibility, care, respect, knowledge of any other human being, the wish to further his life. This is the kind of love the Bible speaks of when it says: love thy neighbour as thyself. Brotherly love is love for all human beings; it is characterised by its very lack of exclusiveness. If I have developed the capacity for love, then I cannot help loving my brothers. In brotherly love there is the experience of union with all men, of human solidarity, of human at-onement. Brotherly love is based on the experience that we all are one. The differences in talents, intelligence, knowledge are negligible in comparison with the identity of the human core common to all men." (63)

However, Fromm argues that brotherly love is undermined by a capitalist system that forces us to compete with each other. "What is the outcome? Modern man is alienated from himself, from his fellow men, and from nature. He has been transformed into a commodity, experiences his life forces as an investment which must bring him the maximum profit obtainable under existing market conditions. Human relations are essentially those of alienated automatons, each basing his security on staying close to the herd, and not being different in thought, feeling or action. While everybody tries to be as close as possible to the rest, everybody remains utterly alone, pervaded by the deep sense of insecurity, anxiety and guilt which always results when human separateness cannot be overcome." (64)

Erich Fromm answer to this problem is to dramatically change society. "If man is to be able to love, he must be put in his supreme place. The economic machine must serve him, rather than he serve it. He must be enabled to share experience, to share work, rather than, at best, share in profits. Society must be organised in such a way that man's social, loving nature is not separated from his social existence, but becomes one with it. If it is true, as I have tried to show, that love is the only sane and satisfactory answer to the problem of human existence, then any society which excludes, relatively, the development of love, must in the long run perish of its own contradiction with the basic necessities of human nature. Indeed, to speak of love is not 'preaching', for the simple reason that it means to speak of the ultimate and real need in every human being. That this need has been obscured does not mean that it does not exist. To analyse the nature of love is to discover its general absence today and to criticise the social conditions which are responsible for this absence. To have faith in the possibility of love as a social and not only exceptional-individual phenomenon, is a rational faith based on the insight into the very nature of man." (65)

Since publication of The Art of Loving has sold more than twenty-five million globally. Lawrence J. Friedman has pointed out: "It is a favourite of my Harvard undergraduates today as it was with my classmates at the University of California half a century ago. For generations, it has been a volume with remarkable ties to its readers' personal and social lives." (66)

Other books by Erich Fromm include Sigmund Freud's Mission (1959), Marx's Concept of Man (1961), The Dogma of Christ (1963), The Heart of Man (1964), The Revolution of Hope (1968), The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (1973) and To Have Or to Be? (1976).

Erich Fromm died on 18th March, 1980.

Primary Sources

(1) Erich Fromm, Psychoanalysis and Sociology (1929)

The application of psychoanalysis to sociology must definitely guard against the mistake of wanting to give psychoanalytic answers where economic, technical, or political facts provide the real and sufficient explanation of sociological questions. On the other hand, the psychoanalyst must emphasize that the subject of sociology, society, in reality consists of individuals, and that it is these human beings, rather than abstract society as such, whose actions, thoughts, and feelings are the object of sociological research.

(2) Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (1941)

Modern European and American history is centred around the effort to gain freedom from the political, economic, and spiritual shackles that have bound men. The battles for freedom were fought by the oppressed, those who wanted new liberties, against those who had privileges to defend. While a class was fighting for its own liberation from domination, it believed itself to be fighting for human freedom as such and thus was able to appeal to an ideal, to the longing for freedom rooted in all who are oppressed. In the long and virtually continuous battle for freedom, however, classes that were fighting against oppression at one stage sided with the enemies of freedom when victory was won and new privileges were to be defended. Despite many reverses, freedom has won battles. Many died in those battles in the conviction that to die in the struggle against oppression was better than to live without freedom. Such a death was the utmost assertion of their individuality.

(3) Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (1941)

The First World War was regarded by many as the final struggle and its conclusion the ultimate victory for freedom. Existing democracies appeared strengthened, and new ones replaced old monarchies. But only a few years elapsed before new systems emerged which denied everything that men believed they had won in centuries of struggle. For the essence of these new systems, which effectively took command of man's entire social and personal life, was the submission of all but a handful of men to an authority over which they had no control.At first many found comfort in the thought that the victory of the authoritarian system was due to the madness of a few individuals and that their madness would lead to their downfall in due time. Others smugly believed that the Italian people, or the Germans, were lacking in a sufficiently long period of training in democracy, and that therefore one could wait complacently until they had reached the political maturity of the Western democracies. Another common illusion, perhaps the most dangerous of all, was that men like Hitler had gained power over the vast apparatus of the state through nothing but cunning and trickery, that they and their satellites ruled merely by sheer force; that the whole population was only the will-less object of betrayal and terror.

In the years that have elapsed since, the fallacy of these arguments has become apparent. We have been compelled to recognize that millions in Germany were as eager to surrender their freedom as their fathers were to fight for it; that instead of wanting freedom, they sought for ways of escape from it; that other millions were indifferent and did not believe the defence of freedom to be worth fighting and dying for. We also recognize that the crisis of democracy is not a peculiarly Italian or German problem, but one confronting every modern state. Nor does it matter which symbols the enemies of human freedom choose: freedom is not less endangered if attacked in the name of anti-Fascism or in that of outright Fascism.

This truth has been so forcefully formulated by John Dewey that I express the thought in his words: "The serious threat to our democracy", he says, "is not the existence of foreign totalitarian states. It is the existence within our own personal attitudes and within our own institutions of conditions which have given a victory to external authority, discipline, uniformity and dependence upon The Leader in foreign countries. The battlefield is also accordingly here - within ourselves and our institutions."

If we want to fight Fascism we must understand it. Wishful thinking will not help us. And reciting optimistic formulae will prove to be as inadequate and useless as the ritual of an Indian rain dance.

(4) Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (1941)

Human nature is neither a biologically fixed and innate sum total of drives nor is it a lifeless shadow of cultural patterns to which it adapts itself smoothly; it is the product of human evolution, but it also has certain inherent mechanisms and laws.

There are certain factors in man's nature which are fixed and unchangeable: the necessity to satisfy the physiologically conditioned drives and the necessity to avoid isolation and moral aloneness. We have seen that the individual has to accept the mode of life rooted in the system of production and distribution peculiar for any given society. In the process of dynamic adaptation to culture, a number of powerful drives develop which motivate the actions and feelings of the individual. The individual may or may not be conscious of these drives, but in any case they are forceful and demand satisfaction once they have developed. They become powerful forces which in their turn become effective in moulding the social process.

(5) Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (1941)

The small or middle-sized business man who is virtually threatened by the overwhelming power of superior capital may very well continue to make profits and to preserve his independence; but the threat hanging over his head has increased his insecurity and powerlessness far beyond what it used to be. In his fight against monopolistic competitors he is staked against giants, whereas he used to fight against equals. But the psychological situation of those independent business men for whom the development of modern industry has created new economic functions is also different from that of the old independent business men.

(6) Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (1941)

The first mechanism of escape from freedom I am going to deal with is the tendency to give up the independence of one's own individual self and to fuse one's self with somebody or something outside oneself in order to acquire the strength which the individual self is lacking. Or, to put it in different words, to seek for new, "secondary bonds" as a substitute for the primary bonds which have been lost.

The more distinct forms of this mechanism are to be found in the striving for submission and domination, or, as we would rather put it, in the masochistic and sadistic strivings as they exist in varying degrees in normal and neurotic persons respectively. We shall first describe these tendencies and then try to show that both of them are an escape from an unbearable aloneness.

The most frequent forms in which masochistic strivings appear are feelings of inferiority, powerlessness, individual insignificance. The analysis of persons who are obsessed by these feelings shows that, while they consciously complain about these feelings and want to get rid of them, unconsciously some power within themselves drives them to feel inferior or insignificant. Their feelings are more than realizations of actual shortcomings and weaknesses (although they are usually rationalized as though they were); these persons show a tendency to belittle themselves, to make themselves weak, and not to master things. Quite regularly these people show a marked dependence on powers outside themselves, on other people, or institutions, or nature. They tend not to assert themselves, not to do what they want, but to submit to the factual or alleged orders of these outside forces. Often they are quite incapable of experiencing neurosis, while the mechanisms of escape are driving forces in normal man.

(7) Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (1941)

While the masochistic person's dependence is obvious, our expectation with regard to the sadistic person is just the reverse: he seems so strong and domineering, and the object of his sadism so weak and submissive, that it is difficult to think of the strong one as being dependent on the one over whom he rules. And yet close analysis shows that this is true. The sadist needs the person over whom he rules, he needs him very badly, since his own feeling of strength is rooted in the fact that he is the master over someone. This dependence may be entirely unconscious.

Thus, for example, a man may treat his wife very sadistically and tell her repeatedly that she can leave the house any day and that he would be only too glad if she did. Often she will be so crushed that she will not dare to make an attempt to leave, and therefore they both will continue to believe that what he says is true. But if she musters up enough courage to declare that she will leave him, something quite unexpected to both of them may happen: he will become desperate, break down, and beg her not to leave him; he will say he cannot live without her, and will declare how much he loves her and so on. Usually, being afraid of asserting herself anyhow, she will be prone to believe him, change her decision and stay. At this point the play starts again. He resumes his old behaviour, she finds it increasingly difficult to stay with him, explodes again, he breaks down again, she stays, and so on and on many times.

(8) Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (1941)

The authoritarian character wins his strength to act through his leaning on superior power. This power is never assailable or changeable. For him lack of power is always an unmistakable sign of guilt and inferiority, and if the authority in which he believes shows signs of weakness, his love and respect change into contempt and hatred. He lacks an "offensive potency" which can attack established power without first feeling subservient to another and stronger power.

The courage of the authoritarian character is essentially a courage to suffer what fate or its personal representative or "leader" may have destined him for. To suffer without complaining is his highest virtue - not the courage of trying to end suffering or at least to diminish it. Not to change fate, but to submit to it, is the heroism of the authoritarian character. He has belief in authority as long as it is strong and commanding. His belief is rooted ultimately in his doubts and constitutes an attempt to compensate them. But he has no faith, if we mean by faith the secure confidence in the realization of what now exists only as a potentiality. Authoritarian philosophy is essentially relativistic and nihilistic, in spite of the fact that it often claims so violently to have conquered relativism and in spite of its show of activity. It is rooted in extreme desperation, in the complete lack of faith, and it leads to nihilism, to the denial of life. In authoritarian philosophy the concept of equality does not exist. The authoritarian character may sometimes use the word equality either conventionally or because it suits his purposes. But it has no real meaning or weight for him, since it concerns something outside the reach of his emotional experience. For him the world is composed of people with power and those without it, of superior ones and inferior ones. On the basis of his sado-masochistic strivings, he experiences only domination or submission, but never solidarity. Differences, whether of sex or race, to him are necessarily signs of superiority or inferiority. A difference which does not have this connotation is unthinkable to him.

(9) Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (1941)

In discussing the psychology of Nazism we have first to consider a preliminary question - the relevance of psychological factors in the understanding of Nazism. In the scientific and still more so in the popular discussion of Nazism, two opposite views are frequently presented: the first, that psychology offers no explanation of an economic and political phenomenon like Fascism, the second, that Fascism is wholly a psychological problem.

The first view looks upon Nazism either as the outcome of an exclusively economic dynamism - of the expansive tendencies of German imperialism, or as an essentially political phenomenon - the conquest of the state by one political party backed by industrialists and Junkers; in short, the victory of Nazism is looked upon as the result of a minority's trickery and coercion of the majority of the population.

The second view, on the other hand, maintains that Nazism can be explained only in terms of psychology, or rather in those of psychopathology. Hitler is looked upon as a madman or as a "neurotic" and his followers as equally mad and mentally unbalanced. According to this explanation, as expounded by Lewis Mumford, the true sources of Fascism are to be found "in the human soul, not in economics". He goes on: "In overwhelming pride, delight in cruelty, neurotic disintegration - in this and not in the Treaty of Versailles or in the incompetence of the German Republic lies the explanation of Fascism."

In our opinion none of these explanations which emphasize political and economic factors to the exclusion of psychological ones - or vice versa - is correct. Nazism is a psychological problem, but the psychological factors themselves have to be understood as being moulded by socio-economic factors; Nazism is an economic and political problem, but the hold it has over a whole people has to be understood on psychological grounds. What we are concerned with in this chapter is this psychological aspect of Nazism, its human basis. This suggests two problems: the character structure of those people to whom it appealed, and the psychological characteristics of the ideology that made it such an effective instrument with regard to those very people.

In considering the psychological basis for the success of Nazism this differentiation has to be made at the outset: one part of the population bowed to the Nazi regime without any strong resistance, but also without becoming admirers of the Nazi ideology and political practice. Another part was deeply attracted to the new ideology and fanatically attached to those who proclaimed it. The first group consisted mainly of the working class and the liberal and Catholic bourgeoisie. In spite of an excellent organization, especially among the working class, these groups, although continuously hostile to Nazism from its beginning up to 1933, did not show the inner resistance one might have expected as the outcome of their political convictions. Their wish to resist collapsed quickly and since then they have caused little difficulty for the regime (excepting, of course, the small minority which has fought heroically against Nazism during all these years). Psychologically, this readiness to submit to the Nazi r e gime seems to be due mainly to a state of inner tiredness and resignation… is characteristic of the individual in the present era even in democratic countries. In Germany one additional condition was present as far as the working class was concerned: the defeat it suffered after the first victories in the revolution of 1918. The working class had entered the post-war period with strong hopes for the realization of socialism or at least for a definite rise in its political, economic, and social position; but, whatever the reasons, it had witnessed an unbroken succession of defeats, which brought about the complete disappointment of all its hopes. By the beginning of 1930 the fruits of its initial victories were almost completely destroyed and the result was a deep feeling of resignation, of disbelief in their leaders, of doubt about the value of any kind of political organization and political activity. They still remained members of their respective parties and, consciously, continued to believe in their political doctrines; but deep within themselves many had given up any hope in the effectiveness of political action.

An additional incentive for the loyalty of the majority of the population to the Nazi government became effective after Hitler came into power. For millions of people Hitler's government then became identical with "Germany". Once he held the power of government, fighting him implied shutting oneself out of the community of Germans; when other political parties were abolished and the Nazi party "was" Germany, opposition to it meant opposition to Germany. It seems that nothing is more difficult for the average man to bear than the feeling of not being identified with a larger group. However much a German citizen may be opposed to the principles of Nazism, if he has to choose between being alone and feeling that he belongs to Germany, most persons will choose the latter. It can be observed in many instances that persons who are not Nazis nevertheless defend Nazism against criticism of foreigners because they feel that an attack on Nazism is an attack on Germany. The fear of isolation and the relative weakness of moral principles help any party to win the loyalty of a large sector of the population once that party has captured the power of the state.

This consideration results in an axiom which is important for the problems of political propaganda: any attack on Germany as such, any defamatory propaganda concerning "the Germans" (such as the "Hun" symbol of the last war), only increases the loyalty of those who are not wholly identified with the Nazi system.

This problem, however, cannot be solved basically by skilful propaganda but only by the victory in all countries of one fundamental truth: that ethical principles stand above the existence of the nation and that by adhering to these principles an individual belongs to the community of all those who share, who have shared, and who will share this belief.

In contrast to the negative or resigned attitude of the working class and of the liberal and Catholic bourgeoisie, the Nazi ideology was ardently greeted by the lower strata of the middle class, composed of small shopkeepers, artisans, and white-collar workers.

(10) Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving (1957)

Man is gifted with reason; he is life being aware of itself; he has awareness of himself, of his fellow man, of his past, and of the possibilities of his future. This awareness of himself as a separate entity, the awareness of his own short life span, of the fact that without his will he is born and against his will he dies, that he will die before those whom he loves, or they before him, the awareness of his aloneness and separateness, of his helplessness before the forces of nature and of society, all this makes his separate, disunited existence an unbearable prison. He would become insane could he not liberate himself from this prison and reach out, unite himself in some form or other with men, with the world outside.

(11) Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving (1957)

Most people are not even aware of their need to conform. They live under the illusion that they follow their own ideas and inclinations, that they are individualists, that they have arrived at their opinions as the result of their own thinking - and that it just happens that their ideas are the same as those of the majority. The consensus of all serves as a proof for the correctness of 'their' ideas. Since there is still a need to feel some individuality, such need is satisfied with regard to minor differences; the initials on the handbag or the sweater, the name plate of the bank teller, the belonging to the Democratic as against the Republican party, to the Elks instead of to the Shriners become the expression of individual differences. The advertising slogan of "it is different" shows up this pathetic need for difference, when in reality there is hardly any left.

This increasing tendency for the elimination of differences is closely related to the concept and the experience of equality, as it is developing in the most advanced industrial societies. Equality had meant, in a religious context, that we are all God's children, that we all share in the same human-divine substance, that we are all one. It meant also that the very differences between individuals must be respected, that while it is true that we are all one, it is also true that each one of us is a unique entity, is a cosmos by itself. Such conviction of the uniqueness of the individual is expressed for instance in the Talmudic statement: "Whosoever saves a single life is as if he had saved the whole world; whosoever destroys a single life is as if he had destroyed the whole world." Equality as a condition for the development of individuality was also the meaning of the conception of the philosophy of the Western Enlightenment. It meant (most clearly formulated by Kant) that no man must be the means for the ends of another man. That all men are equal inasmuch as they are ends, and only ends, and never means to each other. Following the ideas of the Enlightenment, Socialist thinkers of various schools defined equality as abolition of exploitation, of the use of man by man, regardless of whether this use were cruel or 'human'.

In contemporary capitalistic society the meaning of equality has been transformed. By equality one refers to the equality of automatons; of men who have lost their individuality. Equality today means "sameness", rather than "oneness". It is the sameness of abstractions, of the men who work in the same jobs, who have the same amusements, who read the same newspapers, who have the same feelings and the same ideas. In this respect one must also look with some scepticism at some achievements which are usually praised as signs of our progress, such as the equality of women. Needless to say I am not speaking against the equality of women; but the positive aspects of this tendency for equality must not deceive one. It is part of the trend towards the elimination of differences. Equality is bought at this very price: women are equal because they are not different any more. The proposition of Enlightenment philosophy, the soul has no sex, has become the general practice. The polarity of the sexes is disappearing, and with it erotic love, which is based on this polarity. Men and women become the same, not equals as opposite poles. Contemporary society preaches this ideal of unindividualised equality because it needs human atoms, each one the same, to make them function in a mass aggregation, smoothly, without friction; all obeying the same commands, yet everybody being convinced that he is following his own desires. Just as modern mass production requires the standardisation of commodities, so the social process requires standardisation of man, and this standardisation is called `equality'.

Union by conformity is not intense and violent; it is calm, dictated by routine, and for this very reason often is insufficient to pacify the anxiety of separateness. The incidence of alcoholism, drug addiction, compulsive sexualism, and suicide in contemporary Western society are symptoms of this relative failure of herd conformity. Furthermore, this solution concerns mainly the mind and not the body, and for this reason too is lacking in comparison with the orgiastic solutions. Herd conformity has only one advantage: it is permanent, and not spasmodic. The individual is introduced into the conformity pattern at the age of three or four, and subsequently never loses his contact with the herd. Even his funeral, which he anticipates as his last great social affair, is in strict conformance with the pattern.

(12) Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving (1957)

A third way of attaining union lies in creative activity, be it that of the artist, or of the artisan. In any kind of creative work the creating person unites himself with his material, which represents the world outside of himself. Whether a carpenter makes a table, or a goldsmith a piece of jewellery, whether the peasant grows his corn or the painter paints a picture, in all types of creative work the worker and his object become one, man unites himself with the world in the process of creation. This, however, holds true only for productive work, for work in which I plan, produce, see the result of my work. In the modern work process of a clerk, the worker on the endless belt, little is left of this uniting quality of work. The worker becomes an appendix to the machine or to the bureaucratic organisation. He has ceased to be he - hence no union takes place beyond that of conformity.

The unity achieved in productive work is not interpersonal; the unity achieved in orgiastic fusion is transitory; the unity achieved by conformity is only pseudo-unity. Hence, they are only partial answers to the problem of existence. The full answer lies in the achievement of interpersonal union, of fusion with another person, in love.

This desire for interpersonal fusion is the most powerful striving in man. It is the most fundamental passion, it is the force which keeps the human race together, the clan, the family, society. The failure to achieve it means insanity or destruction - self-destruction or destruction of others. Without love, humanity could not exist for a day. Yet, if we call the achievement of interpersonal union 'love', we find ourselves in a serious difficulty. Fusion can be achieved in different ways - and the differences are not less significant than what is common to the various forms of love. Should they all be called love? Or should we reserve the word 'love' only for a specific kind of union, one which has been the ideal virtue in all great humanistic religions and philosophical systems of the last four thousand years of Western and Eastern history?

As with all semantic difficulties, the answer can only be arbitrary. What matters is that we know what kind of union we are talking about when we speak of love. Do we refer to love as the mature answer to the problem of existence, or do we speak of those immature forms of love which may be called symbiotic union? In the following pages I shall call love only by the former. I shall begin the discussion of 'love' with the latter.

Symbiotic union has its biological pattern in the relationship between the pregnant mother and the foetus. They are two, and yet one. They live "together" (sym-biosis), they need each other. The foetus is a part of the mother, it receives everything it needs from her; mother is its world, as it were; she feeds it, she protects it, but also her own life is enhanced by it. In the psychic symbiotic union, the two bodies are independent, but the same kind of attachment exists psychologically.

The passive form of the symbiotic union is that of submission, or if we use a clinical term, of masochism. The masochistic person escapes from the unbearable feeling of isolation and separateness by making himself part and parcel of another person who directs him, guides him, protects him: who is his life and his oxygen, as it were. The power of the one to whom one submits is inflated, may he be a person or a god; he is everything, I am nothing, except inasmuch as I am part of him. As a part, I am part of greatness, of power, of certainty. The masochistic person does not have to make decisions, does not have to take any risks; he is never alone - but he is not independent; he has no integrity: he is not yet fully born. In a religious context the object of worship is called an idol; in a secular context of a masochistic love relationship the essential mechanism, that of idolatry, is the same. The masochistic relationship can be blended with physical, sexual desire; in this case it is not only a submission in which one's mind participates, but also one's whole body. state produced by drugs or under

(13) Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving (1957)

In contrast to symbiotic union, mature love is union under the condition of preserving one's integrity, one's individuality. Love is an active power in man; a power which breaks through the walls which separate man from his fellow men, which unites him with others; love makes him overcome the sense of isolation and separateness, yet it permits him to be himself, to retain his integrity. In love the paradox occurs that two beings become one and yet remain two.

(14) Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving (1957)

For the productive character, giving has an entirely different meaning. Giving is the highest expression of potency. In the very act of giving, I experience my strength, my wealth, my power. This experience of heightened vitality and potency fills me with joy. I experience myself as overflowing, spending, alive, hence as joyous. Giving is more joyous than receiving, not because it is a deprivation, but because in the act of giving lies the expression of my aliveness.

It is not difficult to recognise the validity of this principle by applying it to various specific phenomena. The most elementary example lies in the sphere of sex. The culmination of the male sexual function lies in the act of giving; the man gives himself, his sexual organ, to the woman. At the moment of orgasm he gives his semen to her. He cannot help giving it if he is potent. If he cannot give, he is impotent. For the woman the process is not different, although somewhat more complex. She gives herself too; she opens the gates to her feminine centre; in the act of receiving, she gives. If she is incapable of this act of giving, if she can only receive, she is frigid. With her the act of giving occurs again, not in her function as a lover, but in that as a mother. She gives of herself to the growing child within her, she gives her milk to the infant, she gives her bodily warmth. Not to give would be painful.

In the sphere of material things giving means being rich. Not he who has much is rich, but he who gives much. The hoarder who is anxiously worried about losing something is, psychologically speaking, the poor, impoverished man, regardless of how much he has. Whoever is capable of giving of himself is rich. He experiences himself as one who can confer of himself to others. Only one who is deprived of all that goes beyond the barest necessities for subsistence would be incapable of enjoying the act of giving material things. But daily experience shows that what a person considers the minimal necessities depends as much on his character as it depends on his actual possessions. It is well known that the poor are more willing to give than the rich. Nevertheless, poverty beyond a certain point may make it impossible to give, and is so degrading, not only because of the suffering it causes directly, but because of the fact that it deprives the poor of the joy of giving.

The most important sphere of giving, however, is not that of material things, but lies in the specifically human realm. What does one person give to another? He gives of himself, of the most precious he has, he gives of his life. This does not necessarily mean that he sacrifices his life for the other - but that he gives him of that which is alive in him; he gives him of his joy, of his interest, of his understanding, of his knowledge, of his humour, of his sadness - of all expressions and manifestations of that which is alive in him. In thus giving of his life, he enriches the other person, he enhances the other's sense of aliveness by enhancing his own sense of aliveness. He does not give in order to receive; giving is in itself exquisite joy. But in giving he cannot help bringing something to life in the other person, and this which is brought to life reflects back to him; in truly giving, he cannot help receiving that which is given back to him. Giving implies to make the other person a giver also and they both share in the joy of what they have brought to life. In the act of giving something is born, and both persons involved are grateful for the life that is born for both of them. Specifically with regard to love this means: love is a power which produces love: impotence is the inability to produce love. This thought has been beautifully expressed by Marx: "Assume," he says, "man as man, and his relation to the world as a human one, and you can exchange love only for love, confidence for confidence, etc. If you wish to enjoy art, you must be an artistically trained person; if you wish to have influence on other people, you must be a person who has a really stimulating and furthering influence on other people. Every one of your relationships to man and to nature must be a definite expression of your real, individual life corresponding to the object of your will. If you love without calling forth love, that is, if your love as such does not produce love, if by means of an expression of life as a loving person you do not make yourself a loved person, then your love is impotent, a misfortune." (Karl Marx, National Economics and Philosop hy - 1844) But not only in love does giving mean receiving. The teacher is taught by his students, the actor is stimulated by his audience, the psychoanalyst is cured by his patient - provided they do not treat each other as objects, but are related to each other genuinely and productively.