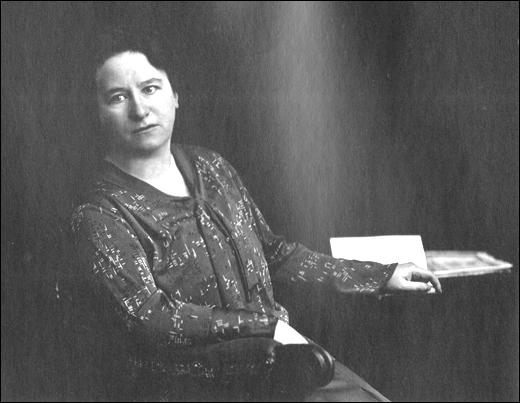

Frieda Fromm-Reichmann

Frieda Reichmann, the daughter of Adolf and Klara Reichmann, was born in Karlsruhe, Germany, on 23rd October, 1889. She was the oldest of three daughters. Her father was a successful businessman and her mother was part of a group that established a preparatory school for girls to prepare them for going off to university. As he did not have any sons, Adolf was willing to allow Frieda to attend medical school in Königsberg in 1908. He said he would be very proud of her if she became a doctor. (1)

Frieda Reichmann was one of the first women to study medicine. She received her medical degree in 1913 and began a residency in neurology studying brain injuries. During the First World War she worked at The Institute for Research into the Consequences of Brain Injuries that had been established to treat German soldiers. Her work led to a better understanding of the physiology and pathology of brain functions. (2)

Reichmann studied the work of Sigmund Freud at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute under Karl Abraham and Max Eitingon. In 1918 she moved to Frankfurt where was employed as an assistant by the psychiatrist Kurt Goldstein. In 1920 she became an assistant physician with Johannes Heinrich Schultz, who become known for his autogenesis training techniques of relaxation. (3)

After the war Goldie Ginsburg introduced Reichmann to Erich Fromm, who was eleven years her junior. In 1923 Fromm and Reichmann opened a therapeutic facility for Jewish patients in Heidelberg. The goal was to nurture simultaneously Jewish identity and psychic health along quasi-socialist lines. As Reichmann pointed out "we first analyze the people and second made them aware of their tradition. As they were both socialists they "didn't want to go on only treating wealthy people." Patients paid what they could or donated their labour in exchange for treatment." (4)

Reichmann later recalled: "We analyzed people as compensation for letting them work. I analyzed the housekeeper, I analyzed the cook. You may imagine what happened if they were in a phase of resistance! It was a wild affair... Erich and I had an affair. We weren't married and nobody was supposed to know about that and actually nobody did know." (5)

Reichmann's biographer, Gail A Hornstein, believed that they made a good match: "Erich was the perfect choice for Frieda. He was charming and warm... Erich also needed to be taken care of, a quality Frieda always found reassuring (in other people)." The wedding took place on 14th May, 1926. "Frieda got a good bargain; she got a man with her father's charm but more brains, who respected her independence." (6) Frieda admitted: "I got what I wanted: a very intelligent, very warm, very well-educated man." (7)

Erich Fromm commenced analytic training with Hanns Sachs and Theodor Reik in 1927. The couple began associating with left-leaning therapists such as Ernst Simmel, Wilhelm Reich, Annie Reich, Helene Deutsch, Edith Jacobson, Edith Weigert and Otto Fenichel who began to take into consideration the social and political impact on the clinical situation. Together they explored ways of "finding a bridge between Marx and Freud". (8)

In 1928 Frieda Fromm-Reichmann set up a private practice at 15 Mönchshofstraße in Berlin. She continued a close relationship with Georg Groddeck, who was director of the Marienhöhe Sanatorium in Baden-Baden. She saw him often and they corresponded regularly. She introduced him to her husband who became his patient: "When I think of all analysts in Germany I knew, he was, in my opinion, the only one with truth, originality, courage and extraordinary kindness. He penetrated the unconscious of his patient, and yet he never hurt. Even if I was never his student in any technical sense, his teaching influenced me more than that of other teachers I had." (9)

Groddeck taught Fromm that "many illnesses are the product of people's lifestyles. If one wants to heal them, one has to change a patient's way of life; only in very few cases can the illness be tackled through so-called specifica." In July 1931 he fell ill with tuberculosis and had to live a long time apart from Frieda. "Groddeck understood Fromm's illness as an expression of his wish to separate from his wife, at the same time showing his difficulty in coming to terms with this idea." (10)

On 30th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Germany's chancellor and over the next few months he banned opposition political parties, free speech, independent cultural organisations and universities and the rule of law. Anti-Semitism became government policy and most of Frieda's non-Jewish friends turned away from her and she had to give up her medical practice. She wrote to Groddeck: "I don't know how my life will unfold in the future; but somewhere I'll find a field of activity and the inner calmness out of which longing can become productive. My husband is better now and I believe that now the psychological requirements for his physical recovery have ripened in him and I am very happy about that." (11)

Fromm-Reichmann left Nazi Germany for Strassburg in Alsace-Lorraine in July, 1933. The following year she spent six months in Palestine, before emigrating to the United States in 1935, where she joined Erich Fromm, Wilhelm Reich, Karen Horney, Ernst Simmel, Otto Fenichel, Franz Alexander and Sandor Rado. At the International Psychoanalytical Association that year President Max Eitingon, pointed out: "We have... had to give up a large number of our most valued German colleagues to the American society." (12)

Soon after Frieda Fromm-Reichmann arrived in America she became a staff member of the Chestnut Lodge Hospital in Rockville, Maryland. Fromm-Reichmann also had a teaching role at the hospital. One of her students claimed: "She was loved and feared by her students in the same time. She was loved because of her warmth, empathy, and insight toward everybody, and feared because of her sharp observation of the neurotic negative counter-transference reactions of psychoanalytic students during their work with patients." (13)

In April 1943, a group of students requested that Erich Fromm teach a clinical course in the American Institute for Psychoanalysis program. Karen Horney rejected the idea and argued that allowing a non-physician to teach clinical courses would make it more difficult for their institute to be accepted as a training program within New York Medical College. At a vote in the faculty council, Horney's proposal was victorious. Fromm, who was working as a training analyst in the privacy of his office, where he was analyzing and supervising students, was officially deprived of training status. As a result, he resigned, along with Clara Thompson, Harry Stack Sullivan and Janet Rioch. (14) Along with eight others, including Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, established their own institution, the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis, and Psychology. (15)

Fromm-Reichmann continued to work at According to Albert Rothenberg: "Although schooled in all of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic treatment precepts, she went beyond these to treat types of patients that Freud himself and most other psychoanalysts or mental health practitioners considered untreatable, primarily those suffering from severe breaks with reality - schizophrenia, manic-depressive bipolar disorder, and patients with psychotic depression. To do this, she used many daring and effective methods such as entering into the figurative and symptomatic world of the patient, treating symptoms as metaphors and smoke screens for underlying conflict and guilt, always focusing on and presenting reality and, both beneath and combined with all these, employing broad empathy, flexibility, courage, and special understanding." (16)

Fromm-Reichmann's longstanding interest in transference and the dynamics of the therapeutic relationship drew her towards the "interpersonal" approach that Harry Stack Sullivan was developing. (17) Sullivan argued that cultural forces are largely responsible for mental illnesses. This search for satisfaction via personal involvement with others led Sullivan to characterize loneliness as the most painful of human experiences. Sullivan shared Fromm-Reichman's view that it was possible to use Freudian psychoanalysis to treat patients with severe mental disorders, particularly schizophrenia. (18)

Fromm-Reichmann met Sullivan soon after arriving in America and he became one of his closest friends. They moved in the "same social circles and were very fond of each other - and it was at Frieda's urging that Sullivan was later brought to Chestnut Lodge to lead an extraordinary four-year seminar that powerfully shaped the ideology of the hospital." (19)

Frieda Fromm-Reichmann died following a heart attack at Chestnut Lodge on 28th April, 1957. In 1964 one of Fromm-Reichmann's former patients, Joanne Greenberg, published a semi-autobiographical novel, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden. Similar to what occurred in the novel, Greenberg was diagnosed with schizophrenia. The character of Dr. Fried in the novel, who helped her recover from schizophrenia is based closely on Fromm-Reichmann. The novel was made into a film in 1977 and a play in 2004. (20)

Primary Sources

(1) Albert Rothenberg, Psychology Today (27th March, 2015)

Frieda Fromm-Reichmann was a pioneering psychoanalyst who spent the major portion of her professional life treating psychotic patients. Born in Germany, she escaped the Hitler Anschluss in 1935 and became a staff member at the Chestnut Lodge Hospital in Maryland where she wrote and treated patients until retirement. Although schooled in all of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic treatment precepts, she went beyond these to treat types of patients that Freud himself and most other psychoanalysts or mental health practitioners considered untreatable, primarily those suffering from severe breaks with reality - schizophrenia, manic-depressive bipolar disorder, and patients with psychotic depression. To do this, she used many daring and effective methods such as entering into the figurative and symptomatic world of the patient, treating symptoms as metaphors and smoke screens for underlying conflict and guilt, always focusing on and presenting reality and, both beneath and combined with all these, employing broad empathy, flexibility, courage, and special understanding.

One instance she has described concerns a professional male patient who had nightly grave and disturbing persecutory delusions, reported by the nurses, of people of various nationalities pursuing him during the night. Trying to escape, he pleaded with each of his persecutors in the person's own language. On the following day, he was in rational contact and could provide no opportunity for discussing the delusions because he could not remember them. After many futile therapeutic attempts, Fromm-Reichmann decided to ask the nurses to awaken her at night at a time when his delusions were apparent. They did so, and she came to the ward to watch him as he climbed from one piece of furniture to another indicating he was running from his persecutors and pleading with them in English, French, German, and Hebrew. She followed him and, also speaking sequentially in each one of the languages, she reassured him that she could not see the persecutors but would try to protect him against them. Then, after 15 or 20 minutes, he quieted down and went to sleep. During the subsequent days she met with him and reminded him of their nocturnal experience several times, ultimately breaking through his denied recall and enabling the beginning of a successful interpretative psychotherapy.

(2) Harriet Freidereich, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann (2018)

After the Nazi takeover in 1933, Fromm-Reichmann left Germany for Strassburg in Alsace-Lorraine. After brief stays in France and Palestine, she immigrated to the United States in 1935. She quickly found a position as resident psychiatrist at Chestnut Lodge, a private sanitarium near Washington, D.C. She developed a very productive working relationship with Harry Stack Sullivan and served as training analyst of the Washington Psychoanalytic Society and the Washington School of Psychiatry, as well as the William Alanson White Institute and the Academy of Psychoanalysis in New York. In 1955, she received a fellowship to study the role of nonverbal communication in therapy at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University.

Fromm-Reichmann succeeded in using intensive psychotherapy to treat schizophrenic and manic-depressive patients who had previously been considered unsuitable for psychoanalysis. She fostered their creative talents and developed fresh insights into the relationship between art and mental illness. A highly gifted clinician and outstanding teacher, she shared her discoveries with large audiences through her popular lectures.

Toward the end of her life, she received international recognition for her contributions to psychotherapy. Her honors and awards include president of the Washington Psychoanalytic Association (1939–1941); Adolf Meyer Award, Association for the Improvement of Mental Hospitals (1952); academic lecture, American Psychiatric Association (1955); and keynote speaker, Second International Congress of Psychiatry, Zurich (1957, posthumous). Suffering from deafness, she kept her unhappiness to herself, while always attempting to cheer and comfort others. She died of a heart attack at Chestnut Lodge on April 28, 1957, deeply mourned by all who knew her.