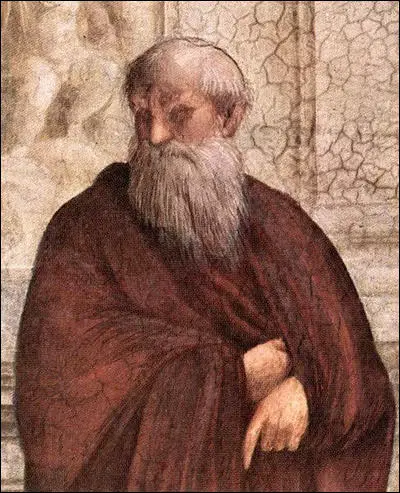

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo was born in the Roman Province of Numidia (modern Algeria) on 13th November 354 AD. His mother, Monica, was a devout Christian, while his father Patricius was a Pagan. It is believed that his family were Berbers, an ethnic group indigenous to North Africa. (1)

Although the early Christians had been persecuted Emperor Constantine, who was exposed to Christianity by his mother, Helena, had declared religious tolerance for Christianity in the Roman Empire in 313 AD. Ten years later he was a Christian and that Christianity was now the official religion of the empire. More significantly, in 325 AD he summoned the Council of Nicaea, the first ecumenical council. Constantine thus established a precedent for the emperor as responsible to God for the spiritual health of their subjects, and thus with a duty to maintain orthodoxy. (2)

Augustine's father owned a few acres and a couple of slaves. The family lived in an inland hill town called Thagaste. (3) Augustine received his early education from his mother. He later pointed out that he learnt Latin, painlessly, at his mother's knee, but hated Greek, which they tried to teach him at school, because he was "urged vehemently with cruel threats and punishments". He added "that a free curiously has more power to make us learn these things than a terrifying obligation". (4)

At the age of 11 was sent to school at Madaurus, a small Numidian city. He admitted: "I had no love of learning, and hated to be driven to it. Yet I was driven to it just the same, and good was done for me, even though I did not do it well, for I would not have learned if I had not been forced to it. For no man does well against his will, even if what he does is a good thing." (5)

He received an education in Latin literature, as well as pagan beliefs and practices. In his autobiography, The Confessions, he recalls an incident where he and some friends stole fruit they did not want from a neighborhood garden. "There was a pear tree close to our own vineyard, heavily laden with fruit, which was not tempting either for its colour or for its flavor. Late one night having prolonged our games in the streets until then, as our bad habit was a group of young scoundrels, and I among them, went to shake and rob this tree. We carried off a huge load of pears, not to eat ourselves, but to dump out to the hogs, after barely tasting some of them ourselves. Doing this pleased us all the more because it was forbidden... I loved my error - not that for which I erred but the error itself. A depraved soul, falling away from security in thee to destruction in itself, seeking nothing from the shameful deed but shame itself." (6)

Monica, Augustine's mother, was a devoted Christian in both faith and practice. She would say her prayers in the local church every day and was often guided by dreams and visions. "As a sceptical teenager he used occasionally to attend church services with her, but found himself mainly engaged in catching the eye of the girls on the other side of the basilica." (7)

Augustine in Carthage

In 371 AD he went to Carthage to continue his education in rhetoric. During this period he lived a hedonistic lifestyle despite the warnings of his mother: "Then whose words were they but thine which by my mother, thy faithful handmaid, thou didst pour into my ears? None of them, however, sank into my heart to make me do anything. She deplored and, as I remember, warned me privately with great solicitude, not to commit fornication; but above all things never to defile another man’s wife. These appeared to me but womanish counsels, which I would have blushed to obey... I did not realize this, and rushed on headlong with such blindness that, among my friends, I was ashamed to be less shameless than they, when I heard them boasting of their disgraceful exploits- - yes, and glorying all the more the worse their baseness was. What is worse, I took pleasure in such exploits, not for the pleasure’s sake only but mostly for praise." (8)

Augustine admitted that by the age of sixteen the "madness of lust which... took the rule over me, and I resigned myself wholly to it?" The following year, Augustine began an affair with a young woman in Carthage. The woman remained his lover for over fifteen years and in 372 AD she gave birth to his son Adeodatus: "In those years I had a mistress, to whom I was not joined in lawful marriage. She was a woman I had discovered in my wayward passion, void as it was of understanding, yet she was the only one; and I remained faithful to her and with her I discovered, by my own experience, what a great difference there is between the restraint of the marriage bond contracted with a view to having children and the compact of a lustful love, where children are born against the parents’ will - although once they are born they compel our love." (9)

Augustine became very interested in Stoicism a school of philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BC. Zeno divided philosophy into three parts: Logic, Physics and Ethics, the end goal of which was to achieve happiness through the right way of living. Stoicism is predominantly a philosophy of personal ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, and was greatly influenced by the teachings of Socrates. For example, he said: "I spend all my time going about trying to persuade you, young and old, to make your first and chief concern not for your bodies nor for your possessions, but for the highest welfare of your souls, proclaiming as I go, wealth does not bring goodness, but goodness brings wealth and every other blessing, both to the individual and to the state." He added that Athenians should be "ashamed that you give your attention to acquiring as much money as possible, and similarly with reputation and honour, and give no attention or thought to truth and understanding and the perfection of your soul". (10)

Augustine was particularly interested in Stoic logic and ethical assertions. According to Socrates, as social beings, the path to happiness for humans is found in accepting the moment as it presents itself, by not allowing oneself to be controlled by the desire for pleasure or fear of pain, by using one's mind to understand the world and to do one's part in nature's plan, and by working together and treating others fairly and justly. Stoics thought the best indication of an individual's philosophy was not what a person said, but how a person behaved. (11)

Augustine also found the ideas of Seneca interesting. Seneca believed that the one and only good thing in life, the "supreme ideal" is virtue. This is usually summarized in ancient philosophy as a combination of four qualities: wisdom (or moral insight), courage, self-control and justice. It enables a man to be "self-sufficient" and therefore immune to suffering. It has been pointed out the "target" Stocism set was far too high for ordinary men and helped to explain "its failure to influence the masses". (12)

Seneca wrote about the way that the The Roman Empire should be ruled appeared in his famous essay, On Clemency (c. A.D. 56), where he urged Emperor Nero to be a tolerant ruler: "That clemency, which is the most humane of virtues, is that which best befits a man, is necessarily an axiom, not only among our own sect, which regards man as a social animal, born for the good of the whole community, but even among those philosophers who give him up entirely to pleasure, and whose words and actions have no other aim than their own personal advantage. If man, as they argue, seeks for quiet and repose, what virtue is there which is more agreeable to his nature than clemency, which loves peace and restrains him from violence? Now clemency becomes no one more than a king or a prince; for great power is glorious and admirable only when it is beneficent; since to be powerful only for mischief is the power of a pestilence. That man's greatness alone rests upon a secure foundation, whom all men know to be as much on their side as he is above them, of whose watchful care for the safety of each and all of them they receive daily proofs, at whose approach they do not fly in terror, as though some evil and dangerous animal had sprung out from its den, but flock to him as they would to the bright and health-giving sunshine." (13)

Seneca also called on citizens to treat their slaves well: "A proposal was once made in the Senate to distinguish slaves from free men by their dress: it was then discovered how dangerous it would be for our slaves to be able to count our numbers. Be assured that the same thing would be the case if no one's offence is pardoned: it will quickly be discovered how far the number of bad men exceeds that of the good. Many executions are as disgraceful to a sovereign as many funerals are to a physician: one who governs less strictly is better obeyed. The human mind is naturally self-willed, kicks against the goad, and sets its face against authority; it will follow more readily than it can be led. As well-bred and high-spirited horses are best managed with a loose rein, so mercy gives men's minds a spontaneous bias towards innocence, and the public think that it is worth observing. Mercy, therefore, does more good than severity." (14)

In about 64 AD Seneca produced On Providence, a short essay in the form of a dialogue with his great friend, Lucilius. He chose the dialogue form to deal with the problem of the co-existence of the Stoic design of providence with the evil in the world. "You have asked me, Lucilius, why, if the world be ruled by providence, so many evils befall good men? The answer to this would be more conveniently given in the course of this work, after we have proved that providence governs the universe, and that God is amongst us: but, since you wish me to deal with one point apart from the whole, and to answer one replication before the main action has been decided, I will do what is not difficult, and plead the cause of the gods." (15)

Seneca explains t hat looks like adversity is in fact a means by which the man exerts his virtues. As such, he can come out of the ordeal stronger than before. "Prosperity comes to the mob, and to low-minded men as well as to great ones; but it is the privilege of great men alone to send under the yoke the disasters and terrors of mortal life: whereas to be always prosperous, and to pass through life without a twinge of mental distress, is to remain ignorant of one half of nature. You are a great man; but how am I to know it, if fortune gives you no opportunity of showing your virtue? God, I say, favours those whom He wishes to enjoy the greatest honours, whenever He affords them the means of performing some exploit with spirit and courage, something which is not easily to be accomplished: you can judge of a pilot in a storm, of a soldier in a battle. How can I know with how great a spirit you could endure poverty, if you overflow with riches? How can I tell with how great firmness you could bear up against disgrace, dishonour, and public hatred, if you grow old to the sound of applause, if popular favour cannot be alienated from you, and seems to flow to you by the natural bent of men's minds?" (16)

It has been argued that some of Seneca's writings bordered on the religious. Robin Campbell has argued: "Christian writers have not been slow to recognize the remarkable close parallels between isolated sentences in Seneca's writings and verses of the Bible... In statements of man's kinship with a beneficent, even loving god and of a belief in conscience as the divinely inspired 'inner light of the spirit', his attitudes are religious beyond anything in Roman state religion, in his day little more than a withered survival of formal worship paid to a host of ancient gods and goddesses... On the other hand the word 'God' or 'the gods' was used by the philosophers more as a time-honoured and convenient expression than as standing for any indispensable or even surely identifiable component of the Stoic system." (17)

Despite his interest in Stoics like Seneca as a young man he allied himself with the Manichees. The founder of this religion was the prophet, Mani, who had been crucified in Persia in 277 AD. Mani was raised in a Jewish-Christian baptism sect. Manichaean writings indicate that Mani received revelations when he was 12 and again when he was 24, and over this time period he grew dissatisfied with the sect he was born into. "Mani did not entirely reject Christianity, but since he held that its teaching was only partially true, but supplemented it by borrowing from other religious and adding his own theories." (18)

The Manichees regarded "the lower half of the body" as the disgusting work of the devil. Mani denied any authority to the Old Testament with its presupposition of the goodness of the material order of things. He much more preferred the New Testament but rejected orthodox Christianity for being too exclusive and negative towards other religious myths and forms of worship. He understood Jesus as a symbol of the plight of all humanity rather than as a historical person. The "crucifixion was no kind of actuality but a mere symbol of the suffering which is the universal human condition." (19)

The religion of Mani's followers, included disgust at the physical world and especially at the human reproductive system. "Procreation imprisoned divine souls in matter, which is inherently hostile to goodness and light. Manichees had a vegetarian diet, and forbade wine. Melons and cucumbers were deemed to contain a particularly large ingredient of divinity. There were two classes, Elect who were strictly obliged to be celibate, and Hearers allowed wives or concubines as long as they avoided procreating children, whether by contraceptives or by confining intercourse to the 'safe' period of the monthly cycle.... Manichee propaganda was combative against the orthodox Catholic Church, which granted married Christians." (20)

Augustine was also attracted to Mani's belief in astrology, which seemed to offer a guide to life without looking too much like a religion. The central question for Mani was the origin of evil. He explained evil as resulting from a primeval and still continuing cosmic conflict between Light and Dark. However, he gradually had doubts about the intellectual basis of the religion. Was Mani right when he asserted that the supremely good Light-power was weak and impotent in conflict with Dark? How could one properly worship a diety so powerless and humiliated? Mani also explained eclipses, by claiming that the sun and the moon were using special veils to shut out the distressing sight of cosmic battles. Augustine was aware that astronomers rejected this theory. Augustine also became disillusioned with the religion when he discovered that the moral life of the Elect, who argued for sinless perfection, turned out to be less celibate than they claimed. (21)

Augustine became very interested in philosophy after reading the work of Cicero and became a teacher of the subject: "I studied the books of eloquence, for it was in eloquence that I was eager to be eminent, though from a reprehensible and vainglorious motive, and a delight in human vanity. In the ordinary course of study I came upon a certain book of Cicero’s, whose language almost all admire, though not his heart. This particular book of his contains an exhortation to philosophy and was called Hortensius. Now it was this book which quite definitely changed my whole attitude and turned my prayers toward thee, O Lord, and gave me new hope and new desires. Suddenly every vain hope became worthless to me, and with an incredible warmth of heart I yearned for an immortality of wisdom and began now to arise that I might return to thee. It was not to sharpen my tongue further that I made use of that book. I was now nineteen; my father had been dead two years, and my mother was providing the money for my study of rhetoric. What won me in it was not its style but its substance." (22)

Augustine was attracted to the ideas expressed by Cicero in his work, On Friendship: "Friendship is nothing else than an accord in all things, human and divine, conjoined with mutual goodwill and affection, and I am inclined to think that, with the exception of wisdom, no better thing has been given to man by the immortal gods. Some prefer riches, some good health, some power, some public honours, and many even prefer sensual pleasures. This last is the highest aim of brutes; the others are fleeting and unstable things and dependent less upon human foresight than upon the fickleness of fortune." (23)

He also read the work of Virgil, Horace, Sallust and Terence. "Cicero's prose and Virgil's poetry were so profoundly stamped on Augustine's mind that he could seldom write many pages without some reminiscence or verbal allusion. In youth he also read with deep admiration Sallust's sombre histories of the Roman Republic and the comedies of Terence. These too were part of the literary air he naturally breathed, and into his prose he would frequently work some turn of phrase from classical Latin literature." (24)

In 383 AD he decided to go to Rome, not, he says, because there the income of a teacher was higher than at Carthage, but because he had heard that classes were more orderly. He established a school in Rome but was disappointed with the apathetic reception. It was the custom for students to pay their fees to the professor on the last day of the term, and many students attended faithfully all term, and then did not pay. (25) The following year he became rhetoric professor at the imperial court at Milan. He had been a supporter of Manichaeanism but began to have doubts after a meeting with Faustus of Mileve, a key exponent of Manichaean theology. One of the reasons for this was his discovery that Faustus was not obeying the rules of celibacy. (26)

Augustine now became interested in the philosophy of Plotinus (204-270 AD), the founder of Neoplatonism, who helped to clarify the teaching of Plato. The metaphysics of Plotinus begins with a Holy Trinity: The One, Spirit and Soul. These three are not equal. The One is supreme, Spirit comes next, and Soul last. The One is sometimes called God, sometimes the Good. Sometimes, the One appears to resemble Aristotle's God, who ignores the created world. "The One is indefinable, and in regard to it there is more truth in silence than in any words whatever." (27)

Plotinus lived an an ascetic life of celibacy and vegetarianism. He argued that the soul's purging could only be achieved only by "flight from the body". By abstinence from meat and from sexual activity, the should could be "gradually emancipated from its bodily fetters". Plotinus, like Cicero, believed that sexual indulgence does not make for mental clarity. Porphyry, a disciple of Plotinus, in a tract on vegetarianism taught that, "just as priests at temples must abstain from sexual intercourse in order to be ritually pure at the time of offering sacrifice, so also the individual soul needs to be equally pure to attain to the vision of God". (28)

Authentic human happiness for Plotinus consists of the true human identifying with that which is the best in the universe. Plotinus was one of the first to introduce the idea that eudaimonia (happiness) is attainable only within consciousness. Plotinus stresses the point that worldly fortune does not control true human happiness, and thus… there exists no single human being that does not either potentially or effectively possess this thing we hold to constitute happiness.” (29)

Real happiness comes from the use of the intellect. The human who has achieved happiness will not be bothered by sickness, discomfort, etc., as his focus is on the greatest things. Authentic human happiness is the result of contemplation and "is determined by the higher phase of the Soul.” (30) Plotinus offers a comprehensive description of his conception of a person who has achieved happiness. A happy person will not sway between happy and sad, because it is a state of mind and is not influenced by the physical world. A living human who has achieved happiness will not change "just because of the body’s discomfort in the physical realm.“ (31)

William Inge argues: "For Plotinus, the course of moral progress begins with the political virtues, which include all the duties of a good citizen; but Plotinus shows no interest in the State as a moral entity. After the political virtues comes purification. The Soul is to put off its lower nature, and to cleanse itself from external stains: that which remains when this is done will be the image of Spirit. Neoplatonism enjoins an ascetic life, but no harsh self-mortification. The conflict with evil is a journey through darkness to light, rather than a struggle with hostile spiritual powers... The desire to be invulnerable underlies all Greek philosophy, and in consequence the need of deep human sympathy is undervalued. The philosopher is not to be perturbed by public or private calamities. Purification leads to the next stage enlightenment. Plotinus puts the philosophic life above active philanthropy, though contemplation for him is incomplete unless it issues in creative activity." (32)

Augustine's mother had followed him to Milan and objected to his relationship with his mistress. Her inferior social status made marriage out of the question in law and in social convention. After the strenuous efforts of his mother, a fiancée, a young girl with a good dowry, was found. However, she was only ten years old and he had to wait two years became in Roman law the minimum age of marriage was twelve. "To modern readers nothing in Augustine's career seems more deplorable... The modern criticism is not of Augustine so much as of the total society in which he was a member." (33)

Although Augustine accepted this marriage, for which he had to abandon his mistress. He was deeply hurt by the loss of his lover. "My mistress was torn from my side as an impediment to my marriage, and my heart which clung to her was torn and wounded till it bled. And she went back to Africa, vowing to thee never to know any other man and leaving with me my natural son by her. But I, unhappy as I was, and weaker than a woman, could not bear the delay of the two years that should elapse before I could obtain the bride I sought. And so, since I was not a lover of wedlock so much as a slave of lust, I procured another mistress - not a wife, of course. Thus in bondage to a lasting habit, the disease of my soul might be nursed up and kept in its vigor or even increased until it reached the realm of matrimony. Nor indeed was the wound healed that had been caused by cutting away my former mistress; only it ceased to burn and throb, and began to fester, and was more dangerous because it was less painful." (34)

Augustine was deeply troubled by his sexual desire: "But now, the more ardently I loved those whose wholesome affections I heard reported - that they had given themselves up wholly to thee to be cured - the more did I abhor myself when compared with them. For many of my years - perhaps twelve - had passed away since my nineteenth, when, upon the reading of Cicero’s Hortensius, I was roused to a desire for wisdom. And here I was, still postponing the abandonment of this world’s happiness to devote myself to the search. For not just the finding alone, but also the bare search for it, ought to have been preferred above the treasures and kingdoms of this world; better than all bodily pleasures, though they were to be had for the taking. But, wretched youth that I was - supremely wretched even in the very outset of my youth - I had entreated chastity of thee and had prayed, “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.” For I was afraid lest thou shouldst hear me too soon, and too soon cure me of my disease of lust which I desired to have satisfied rather than extinguished." (35)

While living in Milan he encountered the Christian orator, Bishop Ambrose. "And to Milan I came, to Ambrose the bishop, famed through the whole world as one of the best of men, thy devoted servant. His eloquent discourse in those times abundantly provided thy people with the flour of thy wheat, the gladness of thy oil, and the sober intoxication of thy wine. To him I was led by thee without my knowledge, that by him I might be led to thee in full knowledge. That man of God received me as a father would, and welcomed my coming as a good bishop should. And I began to love him, of course, not at the first as a teacher of the truth, for I had entirely despaired of finding that in thy Church - but as a friendly man. And I studiously listened to him - though not with the right motive - as he preached to the people. I was trying to discover whether his eloquence came up to his reputation, and whether it flowed fuller or thinner than others said it did. And thus I hung on his words intently, but, as to his subject matter, I was only a careless and contemptuous listener.... Yet I was drawing nearer, gradually and unconsciously." (36)

Ambrose had been the Roman governor of Liguria and Emilia, before becoming a Christian. As bishop, he immediately adopted an ascetic lifestyle, donating all of his money and land to the poor. Giving to the poor was not to be considered an act of generosity towards the fringes of society but a repayment of resources that God had originally bestowed on everyone equally and that the rich had usurped. This idea had a great impact on the development of Augustine's philosophy. (37) As "a statesman, who skillfully and courageously consolidated the power of the Church, he stands out as a man of the first rank". Ambrose warned against intermarriage with pagans, Jews, or heretics. He was also greatly concerned about the subject of sexual morality and wrote "a treatise in praise of virginity, and another deprecating the remarriage of widows". (38)

Augustine eventually broke off his engagement to his eleven-year-old fiancée. Alypius of Thagaste steered Augustine away from marriage, saying that they could not live a life together in the love of wisdom if he married. It seems that a "furtive sexual experience in early adolescence had left Alypius with a lasting sense of revulsion" and found Augustine's delight in sexual relationships "astonishing and unintelligible". In August 386 AD, at the age of 31, Augustine converted to Christianity and dedicated the rest of his life to celibacy. (39)

Augustine later explained the details of his conversion: "Suddenly I heard the voice of a boy or a girl I know not which - coming from the neighboring house, chanting over and over again, “Pick it up, read it; pick it up, read it.” Immediately I ceased weeping and began most earnestly to think whether it was usual for children in some kind of game to sing such a song, but I could not remember ever having heard the like. So, damming the torrent of my tears, I got to my feet, for I could not but think that this was a divine command to open the Bible and read the first passage I should light upon. For I had heard how Anthony, accidentally coming into church while the gospel was being read, received the admonition as if what was read had been addressed to him: 'Go and sell what you have and give it to the poor, and you shall have treasure in heaven; and come and follow me.' (Romans: XIII: 13-14). By such an oracle he was forthwith converted to thee." (40)

Ambrose baptized Augustine, along with his son Adeodatus (which means "gift of God"), in Milan in April 387 AD. The following year he returned home to North Africa. (41) Following the death of his mother and his son aged sixteen, he sold his possessions and gave the money to the poor. The only thing he kept was the family house, which he converted into a monastic foundation for himself and a group of friends. (42)

In 391 AD Augustine was ordained a priest in Hippo Regius, in modern-day Algeria. He became a famous preacher (more than 350 preserved sermons are believed to be authentic), and was noted for combating the Manichaean religion, to which he had formerly adhered. In 395, he became Bishop of Hippo and over the next couple of years he wrote The Confessions, where he attempted to explain why he became a Christian. (43)

It has been claimed that Augustine was the "first modern man" in "the sense that with him the reader feels himself addressed at a level of extraordinary psychological depth and confronted by a coherent system of thought, large parts of which still make potent claims to attention and respect". In doing so he "affected the way in which the West has subsequently thought about the nature of man and what we mean by the word God." (44)

In Book XI, Augustine is concerned with the philosophical issue of time. Time was created when the world was created. God is eternal, in the sense of being timeless; in God there is no before and after, but only an eternal present. God's eternity is exempt from the relation of time; all time is present to Him at once. "This leads Augustine to a very admirable relativistic theory of time." (45) According to Augustine: "The present of things past is memory, the present of things present is sight; and the present of things future is expectation." (46)

Henry Chadwick has argued: "The Confessions is far from being a simple autobiography of a sensitive man, in youth captivated by aesthetic beauty and enthralled by the quest for a sexual fulfillment, but then dramatically converted to Christian faith through a grim period of distress and frustration, finally becoming a bishop known for holding pessimistic opinions about human nature and society." He was criticized by Pelagius, a theologian of British origin, for producing a book that suggested the "totality of human dependence on God for the achievement of the good life". Pelagius "feared the morally enervating effects of telling people to do nothing and to rely entirely on divine grace to impart the will to love the right and the good." (47)

The City of God

Augustine's work The City of God was written to console his fellow Christians after the Visigoths had sacked Rome in 410. It is claimed that many Romans saw it as punishment for abandoning traditional Roman religion for Christianity. Augustine responded by arguing for the truth of Christianity over competing religions and philosophies. His main point being that Christianity's message is spiritual rather than political. Bertrand Russell, the author of History of Western Philosophy (1946) claims that in this great book, Augustine developed "a complete Christian scheme of history, past, present, and future" and explores the "dualism of the kingdom of God and the kingdoms of this world". (48)

In Book I Augustine criticised the pagans, who attributed the calamities of the world, and especially the recent sack of Rome by the Goths, to the Christian religion, and its prohibition of the worship of the gods. However, he pointed out: "Have not those very Romans, who were spared by the barbarians through their respect for Christ, become enemies to the name of Christ? The reliquaries of the martyrs and the churches of the apostles bear witness to this; for in the sack of the city they were open sanctuary for all who fled to them, whether Christian or Pagan. To their very threshold the bloodthirsty enemy raged; there his murderous fury owned a limit. There did such of the enemy as had any pity convey those to whom they had given quarter, lest any less mercifully disposed might fall upon them." (49)

Augustine went on to explain why it was so important to be a Christian: "The good man, though a slave, is free; the wicked, though he reigns, is a slave. To the divine providence it has seemed good to prepare in the world to come for the righteous good things, which the unrighteous shall not enjoy; and for the wicked evil things, by which the good shall not be tormented. But as for the good things of this life, and its ills, God has willed that these should be common to both; that we might not too eagerly covet the things which wicked men are seen equally to enjoy, nor shrink with an unseemly fear from the ills which even good men often suffer. There is, too, a very great difference in the purpose served both by those events which we call adverse and those called prosperous. For the good man is neither uplifted with the good things of time, nor broken by its ills; but the wicked man, because he is corrupted by this world's happiness, feels himself punished by its unhappiness." (50)

Augustine attempted to explain the decline of the Roman Empire: "The lust for power, which of all human vices was found in its most concentrated form in the Roman people as a whole, first established its victory in a few powerful individuals, and then crushed the rest of an exhausted country beneath the yoke of slavery. For when can that lust for power in arrogant hearts come to rest until, after passing from one office to another, it arrives at sovereignty? Now there would be no occasion for this continuous progress if ambition were not all-powerful; and the essential context for ambition is a people corrupted by greed and sensuality." (51)

Augustine took a look at the Ten Commandments: "There are some exceptions made by the divine authority to its own law, that men may not be put to death. These exceptions are of two kinds, being justified either by a general law, or by a special commission granted for a time to some individual. And in this latter case, he to whom authority is delegated, and who is but the sword in the hand of him who uses it, is not himself responsible for the death he deals. And, accordingly, they who have waged war in obedience to the divine command, or in conformity with His laws, have represented in their persons the public justice or the wisdom of government, and in this capacity have put to death wicked men; such persons have by no means violated the commandment, Thou shalt not kill." (52)

In Book V Augustine examines the concepts of fate and free will. He asks what we mean by the word fate: "For when men hear that word, according to the ordinary use of the language, they simply understand by it the virtue of that particular position of the stars which may exist at the time when any one is born or conceived, which some separate altogether from the will of God, while others affirm that this also is dependent on that will. But those who are of opinion that, apart from the will of God, the stars determine what we shall do, or what good things we shall possess, or what evils we shall suffer, must be refused a hearing by all, not only by those who hold the true religion, but by those who wish to be the worshippers of any gods whatsoever, even false gods. For what does this opinion really amount to but this, that no god whatever is to be worshipped or prayed to? Against these, however, our present disputation is not intended to be directed, but against those who, in defense of those whom they think to be gods, oppose the Christian religion. They, however, who make the position of the stars depend on the divine will, and in a manner decree what character each man shall have, and what good or evil shall happen to him, if they think that these same stars have that power conferred upon them by the supreme power of God, in order that they may determine these things according to their will, do a great injury to the celestial sphere, in whose most brilliant senate, and most splendid senate-house, as it were, they suppose that wicked deeds are decreed to be done - such deeds as that, if any terrestrial state should decree them, it would be condemned to overthrow by the decree of the whole human race. What judgment, then, is left to God concerning the deeds of men, who is Lord both of the stars and of men, when to these deeds a celestial necessity is attributed?" (53)

Sexual Desire

Augustine wrote a great deal about physical desire and often quoted the writings of Paul of Tarsus to support his views. In Book XIV he examines the subject of sexual morality: "And the kingdom of death so reigned over men, that the deserved penalty of sin would have hurled all headlong even into the second death, of which there is no end, had not the undeserved grace of God saved some therefrom. And thus it has come to pass, that though there are very many and great nations all over the earth, whose rites and customs, speech, arms, and dress, are distinguished by marked differences, yet there are no more than two kinds of human society, which we may justly call two cities, according to the language of our Scriptures. The one consists of those who wish to live after the flesh, the other of those who wish to live after the spirit; and when they severally achieve what they wish, they live in peace, each after their kind." (54)

"Scripture uses the word flesh in many ways, which there is not time to collect and investigate, if we are to ascertain what it is to live after the flesh (which is certainly evil, though the nature of flesh is not itself evil), we must carefully examine that passage of the epistle which the Apostle Paul wrote to the Galatians, in which he says, Now the works of the flesh are manifest, which are these: adultery, fornication, uncleanness, lasciviousness, idolatry, witchcraft, hatred, variance, emulations, wrath, strife, seditions, heresies, envyings, murders, drunkenness, revellings, and such like: of the which I tell you before, as I have also told you in time past, that they which do such things shall not inherit the kingdom of God. (Galatians 5:19-21) This whole passage of the apostolic epistle being considered, so far as it bears on the matter in hand, will be sufficient to answer the question, what it is to live after the flesh. For among the works of the flesh which he said were manifest, and which he cited for condemnation, we find not only those which concern the pleasure of the flesh, as fornications, uncleanness, lasciviousness, drunkenness, revellings, but also those which, though they be remote from fleshly pleasure, reveal the vices of the soul." (55)

Augustine then goes on to compare the City of this world and the City of God: "In enunciating this proposition of ours, then, that because some live according to the flesh and others according to the spirit, there have arisen two diverse and conflicting cities, we might equally well have said, because some live according to man, others according to God. For Paul says very plainly to the Corinthians, For whereas there is among you envying and strife, are you not carnal, and walk according to man? (1 Corinthians 3:3) So that to walk according to man and to be carnal are the same; for by flesh, that is, by a part of man, man is meant. For before he said that those same persons were animal whom afterwards he calls carnal, saying, For what man knows the things of a man, save the spirit of man which is in him? " (56)

Augustine introduces the story of Adam and Eve to explain his view of sexual morality. God created humankind in God's image and placed Adam in the Garden of Eden. Adam is told that he can eat freely of all the trees in the garden, except for a tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Subsequently, Eve is created from one of Adam's ribs to be Adam's companion. They are innocent and unembarrassed about their nakedness. However, a serpent deceives Eve into eating fruit from the forbidden tree, and she gives some of the fruit to Adam. These acts give them additional knowledge, but it gives them the ability to conjure negative and destructive concepts. God later curses the serpent and the ground. God prophetically tells the woman and the man what will be the consequences of their sin of disobeying God. Then he banishes them from the Garden of Eden. (57) Augustine added: "Adam did not love Eve because she was beautiful; it was his love which made her beautiful." (58)

Augustine explains: "But it is a worse and more damnable pride which casts about for the shelter of an excuse even in manifest sins, as these our first parents did, of whom the woman said, The serpent beguiled me, and I did eat; and the man said, The woman whom You gave to be with me, she gave me of the tree, and I did eat. (Genesis 3:12-13) Here there is no word of begging pardon, no word of entreaty for healing. For though they do not, like Cain, deny that they have perpetrated the deed, yet their pride seeks to refer its wickedness to another - the woman's pride to the serpent, the man's to the woman. But where there is a plain transgression of a divine commandment, this is rather to accuse than to excuse oneself. For the fact that the woman sinned on the serpent's persuasion, and the man at the woman's offer, did not make the transgression less, as if there were any one whom we ought rather to believe or yield to than God." (59)

Augustine then goes on to look at the vice of lust: "Lust may have many objects, yet when no object is specified, the word lust usually suggests to the mind the lustful excitement of the organs of generation. And this lust not only takes possession of the whole body and outward members, but also makes itself felt within, and moves the whole man with a passion in which mental emotion is mingled with bodily appetite, so that the pleasure which results is the greatest of all bodily pleasures. So possessing indeed is this pleasure, that at the moment of time in which it is consummated, all mental activity is suspended. What friend of wisdom and holy joys, who, being married, but knowing, as the apostle says, how to possess his vessel in sanctification and honor, not in the disease of desire, as the Gentiles who know not God (1 Thessalonians 4:4) would not prefer, if this were possible, to beget children without this lust, so that in this function of begetting offspring the members created for this purpose should not be stimulated by the heat of lust, but should be actuated by his volition, in the same way as his other members serve him for their respective ends? But even those who delight in this pleasure are not moved to it at their own will, whether they confine themselves to lawful or transgress to unlawful pleasures; but sometimes this lust importunes them in spite of themselves, and sometimes fails them when they desire to feel it, so that though lust rages in the mind, it stirs not in the body." (60)

According to Augustine, we are all subject as part of our punishment for the sins of Adam and Eve. Chastity is a virtue of the mind. Sexual intercourse in marriage is not sinful, provided the intention is to beget offspring. Even in marriage, as the desire for privacy shows, people are ashamed of sexual intercourse, because "this lawful act of nature is (from our first parents) accompanied with our penal shame". What is shameful about lust is its independence of the will. The need of lust in sexual intercourse is a punishment for Adam's sin, but for which sex might have been divorced from pleasure. "Virtue, it is held, demands a complete control of the will over the body, but such control does not suffice to make the sexual act possible. The sexual act, therefore, seems inconsistent with a perfectly virtuous life." (61)

Augustine explains the connections between shame and lust: "Justly is shame very specially connected with this lust; justly, too, these members themselves, being moved and restrained not at our will, but by a certain independent autocracy, so to speak, are called shameful. Their condition was different before sin. For as it is written, They were naked and were not ashamed, (Genesis 2:25) not that their nakedness was unknown to them, but because nakedness was not yet shameful, because not yet did lust move those members without the will's consent; not yet did the flesh by its disobedience testify against the disobedience of man. For they were not created blind, as the unenlightened vulgar fancy; for Adam saw the animals to whom he gave names, and of Eve we read, The woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was pleasant to the eyes. (Genesis 3:6) Their eyes, therefore were open, but were not open to this, that is to say, were not observant so as to recognize what was conferred upon them by the garment of grace, for they had no consciousness of their members warring against their will. But when they were stripped of this grace, that their disobedience might be punished by fit retribution, there began in the movement of their bodily members a shameless novelty which made nakedness indecent: it at once made them observant and made them ashamed. And therefore, after they violated God's command by open transgression, it is written: And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons. (Genesis 3:7) The eyes of them both were opened, not to see, for already they saw, but to discern between the good they had lost and the evil into which they had fallen." (62)

Augustine argues that in animals the mating instinct operates only at certain times of the year. In man the impulse puts him continually in trouble. Shame is a universal phenomenon. Within marriage itself, where sexual union is acceptable, the act normally takes place in privacy and darkness. "The gulf between dignity and animality made the subject central to much comedy. Why are taboo words coined except to express humanity's combination of fascination and revulsion?" Moreover, "sexual ecstasy swamps the mind", obliterating rational thought. (63)

The Just War

In the The City of God Augustine addressed the idea of the "just war". After describing the horror of past wars he argued: "If I attempted to give an adequate description of these manifold disasters, these stern and lasting necessities, though I am quite unequal to the task, what limit could I set? But, say they, the wise man will wage just wars. As if he would not all the rather lament the necessity of just wars, if he remembers that he is a man; for if they were not just he would not wage them, and would therefore be delivered from all wars. For it is the wrongdoing of the opposing party which compels the wise man to wage just wars; and this wrong-doing, even though it gave rise to no war, would still be matter of grief to man because it is man's wrong-doing. Let every one, then, who thinks with pain on all these great evils, so horrible, so ruthless, acknowledge that this is misery. And if any one either endures or thinks of them without mental pain, this is a more miserable plight still, for he thinks himself happy because he has lost human feeling." (64)

Augustine insisted that individuals should not resort immediately to violence, but quoting the teachings of Paul of Tarsus, he justified the violence of the state: "For rulers hold no terror for those who do right, but for those who do wrong. Do you want to be free from fear of the one in authority? Then do what is right and you will be commended. For he is God's servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain. For he is the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God's wrath on the wrongdoer." (65)

Wars are often the result of the way people come from different types of society: "In the first place, man is separated from man by the difference of languages. For if two men, each ignorant of the other's language, meet, and are not compelled to pass, but, on the contrary, to remain in company, dumb animals, though of different species, would more easily hold intercourse than they, human beings though they be. For their common nature is no help to friendliness when they are prevented by diversity of language from conveying their sentiments to one another; so that a man would more readily hold intercourse with his dog than with a foreigner. But the imperial city has endeavored to impose on subject nations not only her yoke, but her language, as a bond of peace, so that interpreters, far from being scarce, are numberless. This is true; but how many great wars, how much slaughter and bloodshed, have provided this unity! And though these are past, the end of these miseries has not yet come. For though there have never been wanting, nor are yet wanting, hostile nations beyond the empire, against whom wars have been and are waged, yet, supposing there were no such nations, the very extent of the empire itself has produced wars of a more obnoxious description - social and civil wars - and with these the whole race has been agitated, either by the actual conflict or the fear of a renewed outbreak. If I attempted to give an adequate description of these manifold disasters, these stern and lasting necessities, though I am quite unequal to the task, what limit could I set?" (66)

In Contra Faustum Manichaeum Augustine argues that Christians as part of government need not be ashamed to protect peace and punish wickedness when compelled to do so by a government. A just war is when it is (i) a defensive war against an unprovoked aggression, where the consequences would be severe, chronic and certain; (ii) other means on repulsing the aggression have proved inefficient; (iii) the resistance have realistic chances to succeed the damage caused by the war are not greater than those which are intended to be prevented. (67)

Augustine approved self-defence when confronted with an unjust aggression. Nonetheless, he asserted, peacefulness in the face of a grave wrong that could only be stopped by violence would be a sin. Defense of one's self or others could be a necessity, especially when authorized by a legitimate authority: "However, there are some exceptions made by the divine authority to its own law, that men may not be put to death. These exceptions are of two kinds, being justified either by a general law, or by a special commission granted for a time to some individual. And in this latter case, he to whom authority is delegated, and who is but the sword in the hand of him who uses it, is not himself responsible for the death he deals. And, accordingly, they who have waged war in obedience to the divine command, or in conformity with His laws, have represented in their persons the public justice or the wisdom of government, and in this capacity have put to death wicked men; such persons have by no means violated the commandment, Thou shalt not kill." (68)

Christianity and Philosophy

Augustine had studied the early Greek philosophers. There is a very sympathetic account of Plato, whom he places above philosophers such as Socrates and Epicurus. All these were materialists; Plato was not. He saw that God is not any bodily thing, but that all things have their being from God, and from something immutable. Platonists are the best in logic and ethics, and nearest to Christianity. As for Aristotle, he was Plato's inferior, but far above the rest. There are things that can be discovered by reason (as in the philosophers), but for all further religious knowledge we must rely on the Scriptures. (69)

In Book IXX he argues: "Philosophers have expressed a great variety of diverse opinions regarding the ends of goods and of evils, and this question they have eagerly canvassed, that they might, if possible, discover what makes a man happy... According, then, as bodily pleasure is subjected, preferred, or united to virtue, there are three sects. It is subjected to virtue when it is chosen as subservient to virtue. Thus it is a duty of virtue to live for one's country, and for its sake to beget children, neither of which can be done without bodily pleasure. For there is pleasure in eating and drinking, pleasure also in sexual intercourse. But when it is preferred to virtue, it is desired for its own sake, and virtue is chosen only for its sake, and to effect nothing else than the attainment or preservation of bodily pleasure. And this, indeed, is to make life hideous; for where virtue is the slave of pleasure it no longer deserves the name of virtue. Yet even this disgraceful distortion has found some philosophers to patronize and defend it. Then virtue is united to pleasure when neither is desired for the other's sake, but both for their own." (70)

Augustine refers to problems of Cicero dealing with the death of his daughter: "For what flood of eloquence can suffice to detail the miseries of this life? Cicero, in the Consolation on the death of his daughter, has spent all his ability in lamentation; but how inadequate was even his ability here? For when, where, how, in this life can these primary objects of nature be possessed so that they may not be assailed by unforeseen accidents? Is the body of the wise man exempt from any pain which may dispel pleasure, from any disquietude which may banish repose? The amputation or decay of the members of the body puts an end to its integrity, deformity blights its beauty, weakness its health, lassitude its vigor, sleepiness or sluggishness its activity - and which of these is it that may not assail the flesh of the wise man? Comely and fitting attitudes and movements of the body are numbered among the prime natural blessings; but what if some sickness makes the members tremble?" (71)

Christianity encourages people to love other people: "And therefore, although our righteous fathers had slaves, and administered their domestic affairs so as to distinguish between the condition of slaves and the heirship of sons in regard to the blessings of this life, yet in regard to the worship of God, in whom we hope for eternal blessings, they took an equally loving oversight of all the members of their household. And this is so much in accordance with the natural order, that the head of the household was called paterfamilias; and this name has been so generally accepted, that even those whose rule is unrighteous are glad to apply it to themselves. But those who are true fathers of their households desire and endeavor that all the members of their household, equally with their own children, should worship and win God, and should come to that heavenly home in which the duty of ruling men is no longer necessary, because the duty of caring for their everlasting happiness has also ceased; but, until they reach that home, masters ought to feel their position of authority a greater burden than servants their service. And if any member of the family interrupts the domestic peace by disobedience, he is corrected either by word or blow, or some kind of just and legitimate punishment, such as society permits, that he may himself be the better for it, and be readjusted to the family harmony from which he had dislocated himself." (72)

Other Ideas

Soon after being converted to Christianity, Augustine wrote Soliloquies. The book has the form of an "inner dialogue" in which questions are posed, discussions take place and answers are provided, leading to self-knowledge. There are several references to Plato, Cicero and Plotinus. The first book begins with an inner dialogue which seeks to know a soul. In the second book it becomes clear that the soul Augustine wants to get to know is his own. (73) Augustine argued that the prime subject of philosophy should be "the study of God and the human soul". (74)

Augustine also wrote on the nature of music. He restatement of Plato's belief that mathematical principles underlie everything in the universe. "Plato had taught that the very structure of the soul is determined by ratios directly related to the ratios of intervals in music; e.g. an octave is 2 to 1, a fifth 3 to 2, a fourth 4 to 3, a whole tone 9 to 8. Indeed the same ratios governed the distances between the planets. He knew that fitting music is capable of bringing the meaning of words home to the heart. When he was a young man he found music indispensable to his life as a source of consolation... What power of the mind is more astonishing than its ability to recall music without actually hearing any physical sounds? The observation seemed to Augustine a striking demonstration of the soul's transcendence in relation to the body." (75) Augustine agreed with Plato's thesis that between music and the soul there is a "hidden affinity". (76)

Augustine also wrote a substantial and complex treatise "on the origin of evil and on free choice". He states that every ethical action involves the consideration of the cardinal virtues of justice, prudence, self-control and courage. Virtue depends on right and rational choices, and therefore happiness lies in loving goodness of will. By contrast, misery is the product of an evil will. He suggests that evil originated in a misused free choice which neglected eternal goodness, beauty and truth." (77)

Augustine added: "Man is slave to that by which he wishes to find happiness." (78) The longing for authentic happiness is the point at which man discovers God within. "Do not go outside yourself" by looking at the external world, but return into your own personality. The mind is a mirror reflecting divine truth; but it is mutable. Therefore you need to "transcend yourself" and seek the unchanging and eternal ground of all being. Then you will find that "the service of God is perfect freedom". (79)

Death

The Vandals besieged Hippo Regius in the spring of 430. Augustine spent his final days in prayer and repentance. He had described human life as a race towards death and commented that "one should begin each day not with complacency that one has survived another day but with compunction that one more day of one's allotted span has for ever passed." Augustine thought the fear of death could not be so universal or profound unless it were a penalty for sin. (80)

Augustine died on 28th August 430 AD. After his death the Vandals destroyed the city but left Augustine's cathedral and library.

Primary Sources

(1) Augustine of Hippo, Patrologia Latina, Volume 37 (c 393 AD)

The superfluities of the rich are the necessaries of the poor. They who possess superfluities, possess the goods of others.

(2) Augustine of Hippo, Tractates on the Gospel of John (c. 414 AD)

Therefore do not seek to understand in order to believe, but believe that thou mayest understand.

(3) Augustine of Hippo, On the Sermon on the Mount (c. 395 AD)

If anyone will piously and soberly consider the sermon which our Lord Jesus spoke on the mount, as we read it in the Gospel according to Matthew, I think that he will find in it, so far as regards the highest morals, a perfect standard of the Christian life: and this we do not rashly venture to promise, but gather it from the very words of the Lord Himself. For the sermon itself is brought to a close in such a way, that it is clear there are in it all the precepts which go to mould the life. … He has sufficiently indicated, as I think, that these sayings which He uttered on the mount so perfectly guide the life of those who may be willing to live according to them, that they may justly be compared to one building upon a rock.

(4) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) (Book II: Chapter VI)

I became evil for no reason. I had no motive for my wickedness except wickedness itself. It was foul, and I loved it. I loved the self-destruction, I loved my fall, not the object for which I had fallen but my fall itself. My depraved soul leaped down from your firmament to ruin. I was seeking not to gain anything by shameful means, but shame for its own sake.

(5) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) (Book V: Chapter X)

For it still seemed to me “that it is not we who sin, but some other nature sinned in us.” And it gratified my pride to be beyond blame, and when I did anything wrong not to have to confess that I had done wrong.… I loved to excuse my soul and to accuse something else inside me (I knew not what) but which was not I. But, assuredly, it was I, and it was my impiety that had divided me against myself. That sin then was all the more incurable because I did not deem myself a sinner.

(6) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book VIII: Chapter VII

But now, the more ardently I loved those whose wholesome affections I heard reported - that they had given themselves up wholly to thee to be cured - the more did I abhor myself when compared with them. For many of my years - perhaps twelve - had passed away since my nineteenth, when, upon the reading of Cicero’s Hortensius, I was roused to a desire for wisdom. And here I was, still postponing the abandonment of this world’s happiness to devote myself to the search. For not just the finding alone, but also the bare search for it, ought to have been preferred above the treasures and kingdoms of this world; better than all bodily pleasures, though they were to be had for the taking. But, wretched youth that I was - supremely wretched even in the very outset of my youth - I had entreated chastity of thee and had prayed, “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.” For I was afraid lest thou shouldst hear me too soon, and too soon cure me of my disease of lust which I desired to have satisfied rather than extinguished.

(7) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book VIII: Chapter VII

I was saying these things and weeping in the most bitter contrition of my heart, when suddenly I heard the voice of a boy or a girl I know not which - coming from the neighboring house, chanting over and over again, "Take up and read; take up and read." Immediately I ceased weeping and began most earnestly to think whether it was usual for children in some kind of game to sing such a song, but I could not remember ever having heard the like. So, damming the torrent of my tears, I got to my feet, for I could not but think that this was a divine command to open the Bible and read the first passage I should light upon. For I had heard how Anthony, accidentally coming into church while the gospel was being read, received the admonition as if what was read had been addressed to him: "Go and sell what you have and give it to the poor, and you shall have treasure in heaven; and come and follow me" (Matt. 19:21). By such an oracle he was forthwith converted to thee. So I quickly returned to the bench where Alypius was sitting, for there I had put down the apostle’s book when I had left there. I snatched it up, opened it, and in silence read the paragraph on which my eyes first fell: "Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying, but put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh to fulfill the lusts thereof" (Romans 13:13). I wanted to read no further, nor did I need to. For instantly, as the sentence ended, there was infused in my heart something like the light of full certainty and all the gloom of doubt vanished away.

(8) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book X: Chapter VI

But the inner part is the better part; for to it, as both ruler and judge, all these messengers of the senses report the answers of heaven and earth and all the things therein, who said, "We are not God, but he made us." My inner man knew these things through the ministry of the outer man, and I, the inner man, knew all this - I, the soul, through the senses of my body. I asked the whole frame of earth about my God, and it answered, "I am not he, but he made me."

(9) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book X: Chapter XXXV

There is another form of temptation, more complex in its peril. … It originates in an appetite for knowledge. … From this malady of curiosity are all those strange sights exhibited in the theatre. Hence do we proceed to search out the secret powers of nature (which is beside our end), which to know profits not, and wherein men desire nothing but to know.

(10) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book I: Chapter VIII

The good man, though a slave, is free; the wicked, though he reigns, is a slave.

To the divine providence it has seemed good to prepare in the world to come for the righteous good things, which the unrighteous shall not enjoy; and for the wicked evil things, by which the good shall not be tormented. But as for the good things of this life, and its ills, God has willed that these should be common to both; that we might not too eagerly covet the things which wicked men are seen equally to enjoy, nor shrink with an unseemly fear from the ills which even good men often suffer.

There is, too, a very great difference in the purpose served both by those events which we call adverse and those called prosperous. For the good man is neither uplifted with the good things of time, nor broken by its ills; but the wicked man, because he is corrupted by this world’s happiness, feels himself punished by its unhappiness.

(11) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book I: Chapter IX

Virtue and vice are not the same, even if they undergo the same torment…. Thus, in this universal catastrophe, the sufferings of Christians have tended to their moral improvement, because they viewed them with eyes of faith.

(12) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book I: Chapter XXXI

The lust for power, which of all human vices was found in its most concentrated form in the Roman people as a whole, first established its victory in a few powerful individuals, and then crushed the rest of an exhausted country beneath the yoke of slavery.

For when can that lust for power in arrogant hearts come to rest until, after passing from one office to another, it arrives at sovereignty? Now there would be no occasion for this continuous progress if ambition were not all-powerful; and the essential context for ambition is a people corrupted by greed and sensuality.

(13) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book IV: Chapter III

The dominion of bad men is hurtful chiefly to themselves who rule, for they destroy their own souls by greater license in wickedness; while those who are put under them in service are not hurt except by their own iniquity. For to the just all the evils imposed on them by unjust rulers are not the punishment of crime, but the test of virtue. Therefore the good man, although he is a slave, is free; but the bad man, even if he reigns, is a slave, and that not of one man, but, what is far more grievous, of as many masters as he has vices; of which vices when the divine Scripture treats, it says, “For of whom any man is overcome, to the same he is also the bond-slave.

(14) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book IV: Chapter IV

Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms? The band itself is made up of men; it is ruled by the authority of a prince, it is knit together by the pact of the confederacy; the booty is divided by the law agreed on. If, by the admittance of abandoned men, this evil increases to such a degree that it holds places, fixes abodes, takes possession of cities, and subdues peoples, it assumes the more plainly the name of a kingdom, because the reality is now manifestly conferred on it, not by the removal of covetousness, but by the addition of impunity. Indeed, that was an apt and true reply which was given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had been seized. For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, “What thou meanest by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, whilst thou who dost it with a great fleet art styled emperor.”

(15) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book XV: Chapter XXII

Beauty is indeed a good gift of God; but that the good may not think it a great good, God dispenses it even to the wicked.

(16) Augustine of Hippo, Homilies on the First Epistle of John (414 AD)

Shut out the evil love of the world, that you may be filled with the love of God. You are a vessel that was already full: you must pour away what you have, that you may take in what you have not.

A man might say, "The things that are in the world are what God has made. ... Why should I not love what God has made?" ...

Suppose, my brethren, a man should make for his betrothed a ring, and she should prefer the ring given her to the betrothed who made it for her, would not her heart be convicted of infidelity? ... God has given you all these things: therefore, love him who made them.

(17) Augustine of Hippo, Homilies on the First Epistle of John (414 AD)

Beauty grows in you to the extent that love grows, because charity itself is the soul's beauty.

Student Activities

References

(1) Miles Hollingworth, Saint Augustine of Hippo: An Intellectual Biography (2013) pages 51-52

(2) Jeffrey Richards, The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages 476–752 (1979) pages 14-15

(3) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) page 7

(4) Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1946) page 346

(5) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book I: Chapter XII

(6) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book II: Chapter IV

(7) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) page 11

(8) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book II: Chapter III

(9) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book IV: Chapter II

(10) Plato, Apology of Socrates (c. 380 BC)

(11) John Sellars. Stoicism (2006) page 32

(12) Robin Campbell, Letters from a Stoic (2004) pages 16-17

(13) Seneca, On Clemency (c. A.D. 56) chapter III

(14) Seneca, On Clemency (c. A.D. 56) chapter XXIV

(15) Seneca, On Providence (c. AD 64) I

(16) Seneca, On Providence (c. AD 64) IV

(17) Robin Campbell, Letters from a Stoic (2004) page 7

(18) R. S. Pine-Coffin, introduction to The Confessions (2002) page 13

(19) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) page 13

(20) Henry Chadwick, Saint Augustine: Confessions (2008) page xiv

(21) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) page 15

(22) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book III: Chapter IV

(23) Cicero, On Friendship (44 BC) section VI

(24) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) page 5

(25) Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1946) page 348

(26) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) page 14

(27) Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1946) pages 326

(28) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) pages 21 & 25

(29) Plotinus, The Enneads (Book I: 4.4)

(30) Plotinus, The Enneads (Book III: 4.6)

(31) Plotinus, The Enneads (Book I: 4.11)

(32) William Inge, The Philosophy of Plotinus (1918) page xi

(33) Henry Chadwick, Saint Augustine: Confessions (2008) page xvi

(34) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book VI: Chapter XV

(35) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book VIII: Chapter VII

(36) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book V: Chapter XIII

(37) Peter Brown, Through the Eye of the Needle - Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD (2012) page 133

(38) Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1946) page 340

(39) Henry Chadwick, Saint Augustine: Confessions (2008) page xvii

(40) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book VIII: Chapter XII

(41) Eric Leland Saak, High Way to Heaven: The Augustinian Platform between Reform and Reformation (2002) page 290

(42) Mark Vessey, A Companion to Augustine (2015) page 84

(43) Henry Chadwick, A History of Christianity (1995) page 61

(44) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) page 4

(45) Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1946) page 352

(46) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book XI: Chapter XX

(47) Henry Chadwick, Saint Augustine: Confessions (2008) pages ix-x

(48) Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1946) page 304

(49) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book I: Chapter I

(50) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book I: Chapter VIII

(51) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book I: Chapter XXXI

(52) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book II: Chapter XXI

(53) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book V: Chapter I

(54) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book XIV: Chapter I

(55) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book XIV: Chapter II

(56) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book XIV: Chapter IV

(57) Book of Genesis (1-11)

(58) Augustine of Hippo, Enarrationes in Psalmos (c. 395 AD) 132:10

(59) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book XIV: Chapter XIV

(60) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book XIV: Chapter XIV

(61) Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1946) page 358

(62) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book XIV: Chapter XVII

(63) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) page 120

(64) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book XIX: Chapter VII

(65) Epistle to the Romans (13:3-4)

(66) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book IXX: Chapter VII

(67) Augustine of Hippo, Contra Faustum Manichaeum (c. 400 AD) Book XXII: Chapters 69-76

(68) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book II: Chapter XXI

(69) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book XIV: Chapter XV

(70) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book IXX: Chapter I

(71) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book IXX: Chapter IV

(72) Augustine of Hippo, The City of God (412-427 AD) Book IXX: Chapter XVI

(73) Eleonore Stump, The Cambridge Companion to Augustine (2001) page 76

(74) Augustine of Hippo, Soliloquies (386 AD) Book 1: Chapter 7

(75) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) page 47

(76) Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions (397-398 AD) Book X: Chapter XLIX

(77) Augustine of Hippo, De Libero Arbitrio (c. 394 AD)

(78) Augustine of Hippo, De Vera Religione (c. 390 AD) 69

(79) Augustine of Hippo, De Vera Religione (c. 390 AD) 87

(80) Henry Chadwick, Augustine: A Very Short Introduction (2001) pages 45 & 117