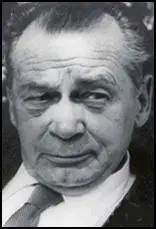

Heinrich Blücher

Heinrich Blücher was born in Berlin on 29th January 1899. His parents were from the working-class and his mother was a laundress. As a young man he joined the Spartacus League, an organization formed by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. (1) He was a gifted, as an orator and as a street fighter. In 1919 he took part in the failed German Revolution. (1a)

In 1919 the Spartacus League became the German Communist Party (KPD). Blücher became one of its first members. In 1922 the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) merged with the KPD. Members now included Paul Levi, Willie Munzenberg, Clara Zetkin, Ernst Toller, Walther Ulbricht, Julian Marchlewski, Ernst Thälmann, Hermann Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frölich, Wilhelm Pieck, Franz Mehring, and Ernest Meyer. The KPD abandoned the goal of immediate revolution, and began to contest Reichstag elections, with some success. In the 1924 General Election the party won 62 seats compared to the 100 seats of the Social Democrat Party. (2)

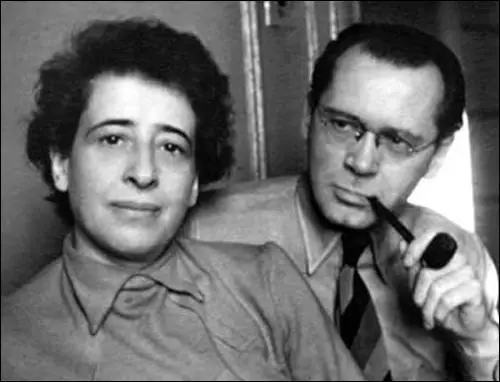

With Blücher, Hannah's world began anew in Paris. Because of who they were, it was still a world of Germans and Jews (a world that had ceased to exist in Germany but was kept alive in France) but it was new because after years of loneliness and disappointment Hannah discovered that love was still a possibility. Blücher was a working-class German leftist in exile; representative of the class of political enemies for whom the Nazis originally invented Dachau.

As a young man at the end of the First World War, he was a Spartacist - a militant revolutionary who fell into the ambit of the newly formed German Communist Party. He studied Marx and Engels and was effective, even gifted, as an orator and as a street fighter,

Ernst Thälmann, replaced Meyer as the Chairman of the KPD in 1925. Thälmann, a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin, willingly put the KPD under the control of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Blücher objected to the Stalinization of the KPD and left the party in 1928. As Clara Zetkin pointed out in a letter to Nikolai Bukharin. "I feel completely alone and alien in this body (KPD), which has changed from being a living political organism into a dead mechanism, which on one side swallows orders in the Russian language and on the other spits them out in various languages, a mechanism which turns the mighty world historical meaning and content of the Russian revolution into the rules of the game for Pickwick Clubs." (3)

Heinrich Blücher: Anti-Nazi Activist

On 4th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler had a meeting with Franz von Papen and decided to work together for a government. It was decided that Hitler would be Chancellor and Von Papen's associates would hold important ministries. "They also agreed to eliminate Social Democrats, Communists, and Jews from political life. Hitler promised to renounce the socialist part of the program, while Von Papen pledged that he would obtain further subsidies from the industrialists for Hitler's use... On 30th January, 1933, with great reluctance, Von Hindenburg named Hitler as Chancellor." (4)

The Reichstag Fire took place on 27th February, 1933, after which Hitler ordered the arrests of leading members of the German Communist Party (KPD) and Social Democratic Party (SDP). that convinced Blücher to leave Nazi Germany. Like many left-wing people from Germany he fled to Paris. He became friends with socialists living in France. This included Raymond Aron was a committed socialist who had been disillusioned with the developments in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. He argued that just as religion is the opium of the masses, ideology is the opium of the intellectuals. (5)

Hannah Arendt

Heinrich Blücher fell in love with Hannah Arendt in the spring of 1936. "Arendt was twenty-nine, Blücher thirty-seven... They fell in love almost at first sight. Both were still formally married but separated from their spouses.... Blücher came from a poor, non-Jewish Berlin working-class background. He was an autodidact who had gone to night school but never graduated... Their attraction was at once intellectual and erotic. Blücher was an autodidact but a highly learned one.... Arendt was fascinated by his intellect. Their relationship now ripened in an atmosphere of intense eroticism." (6)

Arendt's biographer, Daniel Maier-Katkin, has argued: "He (Blücher) was excitable and full of enthusiasms, but still the type who can keep his head when all about are losing theirs. If you were on a lifeboat in a storm in shark-infested water, Blücher would be the companion you would want to have. Tempest-tossed in a dangerous world, Hannah felt safe and secure with Blücher. It would be hard to imagine a steadier or more courageous man, or one more different than Martin Heidegger." (7)

Hannah found herself being able to speak to him about feelings and fears she had never been able to acknowledge before. She also found herself learning a great deal from him. "He had a sense of history and politics that went far beyond the concerns of her Zionist friends. Later she was to acknowledge with unreserved gratitude the enormous influence on her own political thinking of this clever, untutored German who had learned his politics the hard way. And he told his friends that he had at last found the person he needed." (8)

Hannah eventually agreed that she loved Blücher. "I can only truly exist in love. And that is why I was so frightened that I might simply get lost. And so I made myself independent. And about the love of others who branded me as coldhearted, I always thought: if you only knew how dangerous love would be for me. Then when I met you, suddenly I was no longer afraid... It still seems incredible to me that I managed to get both things, the 'love of my life' and a oneness with myself. And yet, I only got the one thing when I got the other. But finally I also know what happiness is." (9)

Dwight Macdonald would later describe Blücher's political identity as a "true, hopeless anarchist." Blücher remained friends with left-wing radicals but became increasingly preoccupied with the arts. Blücher became a close friends with Robert Gilbert, a Jewish artist (real name Robert Winterfeld) had fled from Nazi Germany in 1933. Gilbert, a left-wing songwriter, filmmaker, social critic and entertainer, introduced Blücher to Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht. (10)

In September, 1939, Blücher and all male German immigrants in France were deemed potential dangers to French security and were interred in camps in the provinces. He wrote to Arendt that: "As you can imagine, there are quite a few people here who think of nothing but their own personal destiny." However, because he had a loving partner he was able to cope with being in an internment camp: "I love you with all my heart... My beauty, what a gift of happiness it is to have this feeling, and to know that it will last a whole lifetime and will not change except to grow stronger." (11)

Blücher was eventually released and the couple married on 16th January, 1940. At the beginning of May, with the French government expecting a German invasion, ordered that all Germans except the old, the young, and mothers of children report as enemy aliens to internment camps, the men at Stadion Buffalo and the women at the Velodrome d'Hiver. Arendt observed: "Contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings - the kind that are put into concentration camps by their foes and in internment camps by their friends." (12)

The German Army invaded on 10th May, 1940, Arendt rightly predicted would soon be turned over to the Germans. She therefore decided to escape from the camp. Those that remained were later deported to Auschwitz. She walked for over 200 miles to Montauban, a meeting point for escapees. Blücher also escaped from his camp during a German air-raid. They were hidden by the parents of Daniel Cohn-Bendit until friends in United States managed to obtain emergency visas for the couple. (13)

The United States

Heinrich Blücher and Hannah Arendt arrived in New York City by boat from Lisbon in May 1941. A refugee organization arranged for her to spend two months with an American family in Massachusetts. "The couple who took her in were very high-minded and puritanical; the wife allowed no smoking or drinking in the house... Yet Hannah was impressed by the couple, especially their intense feeling for the democratic political rights and responsibilities of American citizens" (14)

Arendt's first task was to learn English. Within a year it was good enough to become a part-time lecturer in European history at Brooklyn College. She also wrote a biweekly column in the German language newspaper, Aufbau (other contributors included Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig). Blücher worked for a while shoveling chemicals in a New Jersey factory, and then as a research assistant for the Committee for National Morale, an organization whose goal was at first to encourage the United States to enter the Second World War. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor it became an openly anti-fascist group. (15)

The Holocaust

Heinrich Blücher and Hannah Arendt first heard about the extermination of the Jews in Europe in 1943. Arendt later wrote: "We didn't believe this because militarily it was unnecessary and uncalled for. My husband is a former military historian; he understands something about these matters. He said don't be gullible; don't take these stories at face value. They can't go that far! And then a half year we believed it after all, because we had proof... It was really as if an abyss had opened... This ought not to have happened. And I don't mean just the number of victims. I mean the method, the fabrication of corpses and so on - I don't need to go into that. This should not have happened. Something happened there to which we cannot reconcile ourselves. None of us ever can." (16)

However, she explained that if one took seriously what Adolf Hitler had said before the outbreak of the Second World War, the Holocaust could have been predicted. Arendt quoted Hitler as making an announcement to the Reichstag in January, 1939: "I want today once again to make a prophecy: In case the Jewish financiers... succeed once more in hurling the peoples into a world war, the result will be... the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe." (17) Arendt adds that "translated into non-totalitarian language, this meant: I intend to make war and I intend to kill the Jews of Europe." (18)

In 1946, Karl Jaspers sent Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher a copy of his book The Question of German Guilt. Blücher was not impressed: "A Christianized/pietistic/hypocritical nationalizing piece of twaddle... allowing Germans to continue occupying themselves exclusively with themselves for the noble purpose of self-illumination... serving the purpose of extirpating responsibility... This has always been the function of guilt, beginning with original sin... Jasper's whole ethical purification-babble leads him to solidarity with the German National Community and even with the National Socialists, instead of solidarity with those who have been degraded. It seems that... he wishes to redeem the German people.... The Germans don't have to deliver themselves from guilt, but from disgrace. I don't give a damn if they'll roast in hell someday or not, as long as they're prepared to do something to dry the tears of the degraded and the humiliated... Then we could at least say that they have accepted the responsibility and made good, may the Lord spare their souls." (19)

Arendt told Jaspers that he had overlooked the fact that taking responsibility consists of more than accepting defeat and its consequences, or spiritual purification; the highest priority was not introspection, but action on behalf of victims. "We understand very well that you want to leave here and go to Palestine, but, quite apart from that, you should know that you have every right of citizenship here, that you can count on our total support and that mindful of what Germans have inflicted on the Jewish people, we will, in a future German republic, constitutionally renounce anti-Semitism."

She added: "The Nazi crimes, it seems to me, explode the limits of the law; and that is precisely what constitutes their monstrousness. For these crimes, no punishment is severe enough. It may well be essential to hang Göring, but it is totally inadequate. This is, this guilt, in contrast to all criminal guilt, oversteps and shatters any and all legal systems... I don't know how we will ever get out of it, for the Germans are now burdened with thousands or tens of thousands of people who cannot be adequately punished within the legal system; and we Jews are burdened with millions of innocents, by reason of which every Jew alive today can see himself as innocence personified." (20)

In 1948 Hannah Arendt spent two months in New Hampshire. While she was away Heinrich Blücher began an affair with "a vivacious and sensuous young Jewess of Russian descent". Hannah was very unhappy that the affair was known to some of their friends and felt publicly humiliated. However she was "a Weimar Berliner in social mores, she did not define faithfulness narrowly, maritally". Arendt later wrote: "To be sure, in this world there is no eternal love, or ordinary faithfulness. There is nothing but the intensity of the moment, that is, passion, which is even a bit more perishable than man himself." . (21)

During this period Hannah formed a close friendship with Hilde Frankel, the secretary and adored mistress of the theologian Paul Tillich. Hannah described Frankel as "gifted with erotic genius" and with her enjoyed an intimacy "like none she had ever known with a woman". In a letter she wrote to Frankel she expressed her gratitude for the relationship: "Not only for the relaxation which comes from an intimacy like none I have ever known with a woman, but also for the unforgettable good fortune of our nearness, a good fortune of our nearness, a good fortune which is all the greater because you are not an intellectual (a hateful word) and therefore are a confirmation of my very self and of my true beliefs." (22)

The Origins of Totalitarianism

In 1951 Hannah Arendt published her major work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, a "grand synthesis of a decade of thinking about the destruction of the world and civilization into which she had been born". It was dedicated to Heinrich Blücher, who had been her principal thinking partner in this effort, and assisted with the research. Raymond Aron was impressed "by the strength and subtlety of its analyses" and helped establish her prominence as a political thinker and public intellectual. The review in the New York Times said it was "the work of one who has thought as well as suffered". (23)

The book was over a quarter of a million words. In the first two sections of her book, Anti-Semitism and Imperialism, Arendt ranges far and wide through the history in the last 200 to 300 years, identifying events that might be thought to have played that kind of part in the eventual emergence of totalitarianism (the subject of the third section). "Hannah Arendt sets the scene with the nation-states of Europe as they developed at the end of the feudal era. Here was a world of legitimate and limited conflicts: within each nation, conflicts between class and class and between party and party; in Europe as a whole, conflicts between one nation and another." (24)

In the introduction of the book, Hannah Arendt points out that their is a difference between Anti-Semitism and Jew-hatred: "Anti-Semitism, a secular nineteenth-century ideology - which in name, though not in argument, was unknown before the 1870's - and religious Jew-hatred, inspired by the mutually hostile antagonism of two conflicting creeds, are obviously not the same; and even the extent to which the former derives its arguments and emotional appeal from the latter is open to question. The notion of an unbroken continuity of persecutions, expulsions, and massacres from the end of the Roman Empire to the Middle Ages, the modern era, and down to our own time, frequently embellished by the idea that modern Anti-Semitism is no more than a secularized version of popular medieval superstitions, is no less fallacious than the corresponding anti-semitic notion of a Jewish secret society that has ruled, or aspired to rule, the world since antiquity." (25)

Arendt argues that there were several reasons why Anti-Semitism became an important force in the 19th century. "Of all European peoples, the Jews had been the only one without a state of their own and had been, precisely for this reason, so eager and so suitable for alliances with governments and states as such, no matter what these governments or states might represent. On the other hand, the Jews had no political tradition or experience, and were as little aware of the tension between society and state as they were on the obvious risks and power-possibilities of their new role." (26)

Arendt used the example of the S M von Rothschild, a banking enterprise established in 1820 by Amschel Mayer Rothschild in Frankfurt. Branches were established by Salomon Mayer Rothschild (Vienna), Nathan Mayer Rothschild (London), Calmann Mayer Rothschild (Naples) and Jakob Mayer Rothschild (Paris). According to Niall Ferguson, the author, The House of Rothschild (1999), during the 19th century, the Rothschild family possessed the largest private fortune in the world, as well as in modern world history. (27)

Arendt explained: "The history of the relationship between Jews and governments is rich in examples of how quickly Jewish bankers switched their allegiance from one government to the next even after revolutionary changes. It took the French Rothschilds in 1848 hardly twenty-four hours to transfer their services from the government of Louis Philippe to the new short-lived French Republic and again to Napoleon III. The same process repeated itself, at a slightly slower pace, after the downfall of the Second Empire and the establishment of the Third Republic." (28)

Arendt gives the example of Karl Lueger, the leader of the Christian Social Party (CSP) and the mayor of Vienna. Lueger criticised the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) in Austria, the largest political party. Its leader was Victor Adler, and Lueger attacked him for his Jewish origins and his Marxism. Lueger advocated an early form of "fascism". This included a radical German nationalism (meaning the primacy and superiority of all things German), social reform, anti-socialism and anti-semitism. In one speech Lueger commented that the "Jewish problem" would be solved, and a service to the world achieved, if all Jews were placed on a large ship to be sunk on the high seas. (29)

These speeches by Lueger upset Franz Joseph, the Emperor of the Austria–Hungary Empire, who in 1867 had granted the Jewish population equal rights, saying "the civil rights and the country's policy is not contingent in the people's religion". The persecution of Jews under Tsar Alexander III resulted in large-scale emigration from Russia and by 1890 over 100,000 Jews lived in Vienna. This amounted to 12.1% of the total population of the city. Migration from Russia grew even faster after the forced expulsion of Jews from Moscow in 1891. (30)

After the 1895 elections for the Vienna's City Council the Christian Social Party, with the support of the Catholic Church, won two thirds of the seats. Lueger was selected to became mayor of Vienna but this was overruled by Emperor Franz Joseph who disliked his anti-semitism. The Christian Social Party retained a large majority in the council, and re-elected Lueger as mayor three more times, only to have Franz Joseph refuse to confirm him each time. He was elected mayor for a fifth time in 1897, and after the personal intercession by Pope Leo XIII, his election was finally sanctioned later that year. Konrad Heiden has pointed out that without the "all-powerful Catholic Church" Lueger could never have achieved power." (31)

Controversially, Arendt refused to exempt the Jews in Europe from political responsibility for what happened in Nazi Germany: "She rejected the idea that eternal anti-Semitism was simply a fact of history, and argued that a degree of responsibility for the persistence of anti-Semitism lies with the leaders of Jewish communities - the privileged parvenus with wealth and access to power who had governed their impoverished brethren through economic power and philanthropy, consistently aligning themselves with the wrong and ultimately losing side in national and European politics. They preferred monarchies to republics because they instinctively mistrusted the mob. They did not understand, Arendt argued, that over time, as various classes of society came into conflict with the state, ordinary people became anti-Semitic because the Jewish leadership invariably aligned their communities with whoever was in power. She did not offer this as a justification for what happened, but as part of an effort to understand how it could have happened." (32)

The book included a critique of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin and the totalitarian political system they had established. The term "totalitario" was coined by Giovanni Gentile, the Italian political theorist who had helped establish the corporate state under Benito Mussolini in the 1920s. He used the word to refer to the totalizing structure, goals, and ideology of a state directed at the mobilization of entire populations and control of all aspects of social life including business, labour, religion and politics. (33)

Arendt suggests that totalitarian dictators need to develop a special relationship with the masses. Hitler, for example, exercised a "magic spell" over his listeners. This fascination, what the German historian, Gerhard Ritter, has described as "the strange magnetism that radiated from Hitler in such a compelling manner" rested "on the fanatical belief of this man in himself." She adds: "The hair-raising arbitrariness of such fanaticism holds great fascination for society because for the duration of the social gathering it is freed from the chaos of opinions that it constantly generates." (34)

Fascist dictators aim and succeed in organizing masses, not classes. "Totalitarian movements are possible wherever there are masses who for one reason or another have acquired the appetite for political organization. Masses are not held together by a consciousness of common interest and they lack that specific class articulateness which is expressed in determined, limited, and obtainable goals. The term masses applies only where we deal with people who either because of sheer numbers, or indifference, or a combination of both, cannot be integrated into any organization based on common interest, into political parties or municipal governments or professional organizations or trade unions. Potentially, they exist in every country and form the majority of those large numbers of neutral, politically indifferent people who never join a party and hardly ever go to the polls." (35)

Ardent pointed out that it was characteristic of the rise of the Nazi movement in Germany "that they recruited their members from this mass of apparently indifferent people whom all other parties had given up as too apathetic or too stupid for their attention. The result was that the majority of their membership consisted of people who never before had appeared on the political scene. This permitted the introduction of entirely new methods into political propaganda, and indifference to the arguments of political opponents; these movements not only placed themselves outside and against the party system as a whole, they found a membership that had never been reached, never been 'spoiled' by the party system. Therefore they did not need to refute opposing arguments and consistently preferred methods which ended in death rather than persuasion, which spelled terror rather than conviction." (36)

Hitler knew how to exploit feelings of nationalism: "Coming from the class-ridden society of the nation-state, whose cracks had been cemented with nationalistic sentiment, it is only natural that these masses, in the first helplessness of their new experience, have tended toward an especially violent nationalism, to which mass leaders have yielded against their own instincts and purposes for purely demagogic reasons... The most gifted mass leaders of our time have still risen from the mob rather than from the masses. Hitler's biography reads like a textbook example in this respect." (37)

Stalin gained power in a different way from Hitler. He had been a member of the Bolsheviks that had formed a revolutionary government in 1917. It was not until the death of Lenin that he could impose himself as a dictator. "All these new classes and nationalities were in Stalin's way when he began to prepare the country for totalitarian government. In order to fabricate an atomized and structureless mass, he had first to liquidate the remnants of power in the Soviets which, as the chief organ of national representation, still played a certain role and prevented absolute rule by the party hierarchy." (38)

In a time of crisis, to achieve totalitarian power, involves a temporary alliance between the mob and the elite. "What is more disturbing to our peace of mind than the unconditional loyalty of members of totalitarian movements, and the popular support of totalitarian regimes, is the unquestionable attraction these movements exert on the elite, and not only on the mob elements in society... This attraction for the elite is as important a clue to the understanding of totalitarian movements as their more obvious connection with the mob. It indicates the specific atmosphere, the general climate in which the rise of totalitarianism takes place... This breakdown, when the smugness of spurious respectability gave way to anarchic despair, seemed the first great opportunity for the elite as well as the mob. This is obvious for the new mass leaders whose careers reproduce the features of earlier mob leaders: failure in professional and social life, perversion and disaster in private life." (39)

Propaganda is a vital aspect of totalitarian governments: "The terrible demoralizing fascination in the possibility that gigantic lies and monstrous falsehoods can eventually be established as unquestioned facts, that man may be free to change his own past at will, and that the difference between truth and falsehood may cease to be objective and become a mere matter of power and cleverness, of pressure and infinite repetition. Not Stalin's and Hitler's skill in the art of lying but the fact that they were able to organize the masses into a collective unit to back up their lies with impressive magnificence, exerted the fascination." (40)

The finishing point in the narrative is the Nazi extermination camps. "Hannah Arendt portrays the terror and the genocide for which those camps were created as the necessary goal of the whole whirling, on-driving movement of Nazi totalitarianism. And she wants to ask: how did these unforeseeable and previously unimaginable horrors appear in man's history? Can we begin to understand this unspeakable outrage to all our once cherished conceptions of man's dignity - or at least of man's elementary rationality and common sense?" (41)

Mary McCarthy wrote to Hannah Arendt soon after reading The Origins of Totalitarianism: "It seems to me a truly extraordinary piece of work, an advance in human thought of, at the very least, a decade, and also engrossing and fascinating in the way a novel is: i.e. that it says something on nearly every page that is novel, that one could not have anticipated from what went before but that one often recognized as inevitable and foreshadowed by the underlying plot of ideas." (42)

McCarthyism

In 1952 both Heinrich Blücher and Hannah Arendt became American citizens. They became friends with a large number of left-wing intellectuals including Dwight MacDonald, Sidney Hook, Randall Jarrell, Mary McCarthy, Philip Rahv, Irving Howe, Clement Greenberg, Frederick Dupee, William Phillips, Harold Rosenberg, Daniel Bell, Delmore Schwartz, William Barrett, Diana Trilling, Lionel Trilling and Alfred Kazin. Most of these figures were associated with the Partisan Review, a journal established by some members of the American Communist Party in 1934 as an alternative to the pro-Stalin New Masses, but by the 1950s was being secretly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency. (43)

The couple became especially close to the poet, Randall Jarrell. He was a regular visitor to their house and he wrote to his wife that they were "a scream together", that sometimes they had "little cheerful mock quarrels and that they shared household duties such as washing dishes, and that "she kids him a little more than he kids her" and "they seem a very happy married couple". Jarrell characterized the relationship between Hannah and Heinrich as a "dual monarchy". (44)

After one of their weekends Jarrell wrote to Hannah that he found Heinrich awe-inspiring because encountering a perso9n even more enthusiastic than himself was like "the second fattest man in the world meeting the fattest." Jarrell committed suicide at the age of fifty-one. He was walking along a country road at night when he jumped in front of a car. Hannah said the last time she saw him, not long before his death, that the laughter in him was almost gone and he was almost ready to admit defeat. (45)

In July 1952, Heinrich Blücher was employed by Bard College, a progressive liberal arts school not far from New York City, as a tutor in the philosophy department. He also became active in opposition to Joseph McCarthy who was attempting to blacklist those working in the arts and education who were former members of the American Communist Party. Blücher failed to persuade the American Committee for Cultural Freedom to pass a resolution condemning what had become known as McCarthyism. (46)

Hannah Arendt, had for over 20 years opposed the totalitarian aspects of communist thought and Soviet practice, but she grew increasingly concerned as McCarthyism and the work of the House Un-American Activities Committee threatened to raise anti-communism into a full-fledged attack on traditional American conceptions of civil liberties. Her experiences in Nazi Germany when "the German intelligentsia in the 1930s left Arendt with little confidence that intellectuals would have the courage or foresight to stand up for fundamental values". (47)

In March 1953, Arendt published an article in Commonweal Magazine about the court-case where Whittaker Chambers was the main witness against Alger Hiss. Arendt observed that the ex-communists still had communism at the centre of their lives, opposing it now with the same dangerous zeal with which they had once embraced it. She argued that fighting totalitarianism with totalitarian methods, which people like Chambers knew would be disastrous. Arendt finished her article by arguing that any attempt to "make America more American" can only destroy it. (48)

This was a brave article as Congress had just passed the McCarran-Walter Act, that authorized the deportation of recently arrived immigrants who had been members of the communist party or fellow travellers. Heinrich Blücher was especially vulnerable as he had been a former member of the German Communist Party. Arendt was supported by Mary McCarthy who was also publicly outspoken against the dangers of extreme anti-communism and talked about giving up her writing career in order to go to law school and become an advocate for civil liberties in the courts. (49)

In June, 1953, Hannah Arendt wrote to Karl Jaspers about the political crisis in America. She praised Albert Einstein for taking a public position on McCarthyism, encouraging intellectuals to risk contempt of Congress rather than testify. "Politically that is the only correct thing to do; what makes it difficult on the practical level isn't the legal implications but the loss of one's job." She complained that Sidney Hook, a major figure in the American Committee for Cultural Freedom, called Einstein's suggestion "ill considered and irresponsible". (50)

Some figures in the media, such as writers Freda Kirchway, George Seldes and I. F. Stone, and cartoonists, Herb Block and Daniel Fitzpatrick, continued to campaign against Joseph McCarthy. Other figures in the media, who had for a long time been opposed to McCarthyism but were frightened to speak out, now began to get the confidence to join the counter-attack. Edward Murrow, the experienced broadcaster, used his television programme, See It Now, on 9th March, 1954, to criticize McCarthy's methods. "We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law... We proclaim ourselves, as indeed we are, the defenders of freedom, wherever it continues to exist in the world, but we cannot defend freedom abroad by deserting it at home." (51)

Harry S. Truman, the former president of the United States spoke out against McCarthyism: "It is now evident that the present Administration has fully embraced, for political advantage, McCarthyism. I am not referring to the Senator from Wisconsin. He is only important in that his name has taken on the dictionary meaning of the word. It is the corruption of truth, the abandonment of the due process law. It is the use of the big lie and the unfounded accusation against any citizen in the name of Americanism or security. It is the rise to power of the demagogue who lives on untruth; it is the spreading of fear and the destruction of faith in every level of society." (52)

Popular newspaper columnists such as Walter Lippmann and Jack Anderson also became more open in their attacks on McCarthy. Lippmann wrote in the The Washington Post: "McCarthy's influence has grown as the President has appeased him. His power will cease to grow and will diminish when he is resisted, and it has been shown to our people that those to whom we look for leadership and to preserve our institutions are not afraid of him." (53)

The senate investigations into the United States Army were televised and this helped to expose the tactics of Joseph McCarthy. Leading politicians in both parties, had been embarrassed by McCarthy's performance and on 2nd December, 1954, a censure motion condemned his conduct by 67 votes to 22. Arendt wrote to Karl Jaspers: "McCarthy is finished. The historians will no doubt busy themselves someday writing about what has happened here and how much extremely valuable china got smashed in the process... What I see in it is totalitarian elements springing from the womb of society, of mass society itself, without any movement or clear ideology." (54)

Final Years

Hannah Arendt continued to publish controversial books. A collection of essays, On Revolution (1963) upset many on the left as she criticised the outcome of both the French Revolution (1789) and the Russian Revolution (1917). This view was attacked by the Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm, who argued that Arendt's approach was selective, both in terms of cases and the evidence drawn from them. For example, he claimed that Arendt unjustifiably excludes revolutions that did not occur in the West, such as Chinese Revolution (1911) and finds the link between Arendtian revolutions and history to be "as incidental as that of medieval theologians and astronomers". (55)

The anthology of essays, Men in Dark Times (1968) presents intellectual biographies of some creative and moral figures of the twentieth century, such as Walter Benjamin, Karl Jaspers, Bertolt Brecht and Isak Dinesen. In her article on Rosa Luxemburg, she argues that her execution severely damaged the chances of socialism in Germany: "Rosa Luxemburg's death became the watershed between two eras in Germany; and it became the point of no return for the German Left. All those who had drifted to the Communists out of bitter disappointment with the Socialist Party were even more disappointed with the swift moral decline and political disintegration of the Communist Party, and yet they felt that to return to the ranks of the Socialists would mean to condone the murder of Rosa." (56)

Hannah Arendt continued to have contact with Martin Heidegger and in the last nine years of her life the couple exchanged seventy-five letters. Hannah also visited him and Karl Jaspers in Europe in September 1968. She wrote to Heinrich Blücher that Jaspers could barely walk even with a walker and that he should be in a wheelchair. Hannah returned in February, 1969, to attend Jaspers's funeral in Basel. She also took this opportunity to visit Heidegger in Freiburg. (57)

Heinrich Blücher was taken ill on 30th October, 1970. He was having lunch with Hannah when he experienced chest pains. He made his way to the couch, and there suffered a major heart attack. Hannah called for an ambulance and held his hand. "That's it," he said. He died at Mount Sinai Hospital a few hours later. He was buried on 4th November. She asked her friend, Mary McCarthy, "How am I to live now?" She immediately returned to teaching: "I function all right, but know that the slightest mishap could throw me off balance. I don't think I told you that for ten long years I had been constantly afraid that just a sudden death would happen. This fear frequently bordered on real panic. Where the fear was and the panic there is now sheer emptiness." (58)

Primary Sources

(1) Amos Elon, New York Review of Books (5th July, 2001)

Arendt and Blücher met in a café in the rue Soufflot frequented by their friend Walter Benjamin and other German émigrés. Arendt was twenty-nine, Blücher thirty-seven. Both were fugitives from the Nazis. Arendt had escaped without papers across the Czech border, following a short stay in a Gestapo prison for engaging in allegedly subversive research in a Berlin public library. Blücher, a former Communist militant, got out by the same route. Unlike Arendt, who had a steady job at a Jewish welfare organization, he lacked the requisite permis de séjour and had to move frequently from hotel to hotel.

They fell in love almost at first sight. Both were still formally married but separated from their spouses. By background and education they could not have been more different. Arendt was the sheltered only daughter in a conservative, upper-middle-class Jewish-Prussian family (her grandfather had been president of the Königsberg city parliament). She was a former student of Martin Heidegger and Karl Jaspers, Germany’s leading philosophers, who had directed her doctoral dissertation, Augustine’s Idea of Love, which was published in Berlin in 1929. Blücher came from a poor, non-Jewish Berlin working-class background. He was an autodidact who had gone to night school but never graduated, a bohemian who until 1933 had worked in German cabarets.

“Everything,” Arendt conceded, spoke against a possible liaison. But what was this “everything,” she asked rhetorically, “apart from prejudices and difficulties and petty fears?” Almost immediately after they met, Blücher knew, as he put it, that they belonged together. Arendt was at first hesitant. His insistent wooing broke down her reserve. Blücher was a dissident Marxist. Dwight Macdonald later said that he was a “true, hopeless anarchist.” Blücher was sharply critical of the Stalinists among the German intellectual exiles and foresaw the German–Soviet pact of 1939. He criticized Brecht’s Lesebuch für Städtebewohner for combining the worst elements of Communist and Nazi propaganda. Arendt, the future author of The Origins of Totalitarianism, who until this point had been interested in politics only marginally, later told Karl Jaspers that Blücher had taught her “to think politically and see historically.”

Their attraction was at once intellectual and erotic. Blücher was an autodidact but a highly learned one. As his students at the New School and at Bard College later found, he was not a writer but a master of the spoken word and a serious and original thinker. Arendt was fascinated by his intellect. Their relationship now ripened in an atmosphere of intense eroticism.

(2) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010)

Hannah met and fell in love with Heinrich Blücher in the spring of 1936. Blücher was strong, smart, handsome - in the sort of way that movie stars are handsome - and more than that a good man in a storm. He was excitable and full of enthusiasms, but still the type who can keep his head when all about are losing theirs. If you were on a lifeboat in a storm in shark-infested water, Blücher would be the companion you would want to have. Tempest-tossed in a dangerous world, Hannah felt safe and secure with Blücher. It would be hard to imagine a steadier or more courageous man, or one more different than Martin Heidegger.

With Blücher, Hannah's world began anew in Paris. Because of who they were, it was still a world of Germans and Jews (a world that had ceased to exist in Germany but was kept alive in France) but it was new because after years of loneliness and disappointment Hannah discovered that love was still a possibility. Blücher was a working-class German leftist in exile; representative of the class of political enemies for whom the Nazis originally invented Dachau.

As a young man at the end of the First World War, he was a Spartacist - a militant revolutionary who fell into the ambit of the newly formed German Communist Party. He studied Marx and Engels and was effective, even gifted, as an orator and as a street fighter, but grew disenchanted with communism as the movement became increasingly dominated by Russian influences after Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, the leaders of the German Communist Party, were murdered (with the tacit approval of Friedrich Ebert, the Social Democratic president of Germany) by right-wing killing squads.

(3) Derwent May, Hannah Arendt (1986)

Hannah Arendt met Heinrich Blücher in the spring of 1936, when she was twenty-nine and he was thirty-seven. He was very unlike the solemn Heidegger, or the earnest Günther Stern. He was the son of a laundress from a Berlin suburb, and was amusing, impulsive, self-taught. He had fought with the Spartacists in Berlin in 1918 and 1919, and had been one of the first members of the German Communist Party, which had been formed during those battles; he had been a song-writer, a film critic, an amateur psychoanalyst.

References

(1) Derwent May, Hannah Arendt (1986) page 47

(1a) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010) page 107

(2) Dieter Nohlen and Philip Stover, Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook (2010) page 790

(3) Clara Zetkin, letter to Nikolai Bukharin (March, 1929)

(4) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 154

(5) Alexandre Koyre, From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe (1958)

(6) Amos Elon, New York Review of Books (5th July, 2001)

(7) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010) page 106

(8) Derwent May, Hannah Arendt (1986) page 47

(9) Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher, Within Four Walls: The Correspondence Between Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher (2000) pages 40-41

(10) Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World (2004) pages 122-130

(11) Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher, Within Four Walls: The Correspondence Between Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher (2000) page 48

(12) Hannah Arendt, The Jew as Pariah: Jewish Identity and Politics in the Modern Age (1978) pages 62-63

(13) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010) pages 112-113

(14) Derwent May, Hannah Arendt (1986) pages 82-83

(15) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010) pages 181-182

(16) Hannah Arendt, interviewed by Günter Gaus (28th October, 1964)

(17) Adolf Hitler, quoted by Joseph Goebbels in The Goebbels Diaries (1948) page 148

(18) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) page 457

(19) Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher, Within Four Walls: The Correspondence Between Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher (2000) pages 84-85

(20) Hannah Arendt, letter to Karl Jaspers (17th August 1946)

(21) Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World (2004) pages 239-240

(22) Hannah Arendt, letter to Hilde Frankel (January, 1950)

(23) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010) page 154

(24) Derwent May, Hannah Arendt (1986) page 62

(25) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) page xiii

(26) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) page 29

(27) Niall Ferguson, The House of Rothschild (1999), page 481-85

(28) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) page 30

(29) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 216

(30) Shumuel Ettinger, Jewish Emigration in the 19th Century (October 2019)

(31) Konrad Heiden, Hitler: A Biography (1936) page 57

(32) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010) page 158

(33) Stanley G. Payne, Fascism: Comparison and Definition (1980) page 73

(34) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) pages 399-400

(35) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) page 407

(36) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) page 408

(37) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) page 415

(38) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) pages 418-419

(39) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) pages 427-428

(40) Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) (2017 edition) page 437

(41) Derwent May, Hannah Arendt (1986) page 61

(42) Mary McCarthy, letter to Hannah Arendt (April, 1951)

(43) Hugh Wilford, The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America (2008) pages 103-104

(44) Mary Jarrell (editor), Randall Jarrell's Letters: An Autobiographical and Literary Selection (1985) pages 392-393

(45) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010) page 196

(46) Derwent May, Hannah Arendt (1986) page 78

(47) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010) page 205

(48) Hannah Arendt, Commonweal Magazine (20th March, 1953)

(49) Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (1958) page 241

(50) Hannah Arendt, letter to Karl Jaspers (June, 1953)

(51) Edward Murrow, See It Now (9th March, 1954)

(52) Harry S. Truman, New York Times (17th November, 1953)

(53) Walter Lippmann, The Washington Post (1st March, 1954)

(54) Hannah Arendt, letter to Karl Jaspers (December, 1954)

(55) Eric Hobsbawm, Revolutionaries: Contemporary Essays (1973) pages 201–209

(56) Hannah Arendt, Men in Dark Times (1968) page 421

(57) Daniel Maier-Katkin, Stranger from Abroad: Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Friendship and Forgiveness (2010) page 299

(58) Hannah Arendt, letter to Mary McCarthy (November, 1970)