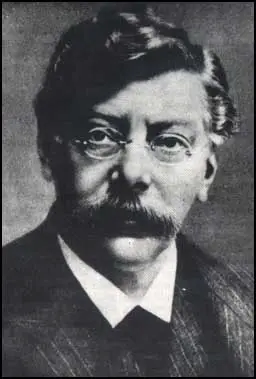

Victor Adler

Victor Adler, the son of a Jewish merchant, was born in Prague on 24th June 1852. He attended the Catholic Schottenstift gymnasium before studying chemistry and medicine at the University of Vienna. After graduating he worked at the psychiatric department of the Vienna General Hospital.

In 1878 he had married his wife Emma, their son Friedrich Adler was born in 1879. Adler became a follower of Karl Marx and became very active in politics. He also published the socialist journal Gleichheit (Equality). According to Karl Kautsky: "Adler’s activity was recognised with joy by the great majority of comrades from the beginning – recognised, took though on no account with joy, by our opponents. In their own way, of course. The tram-drivers’ strike gave them the first occasion. For incitement, abuse of the authorities, and praising illegal actions, Adler and Bretschneider, the responsible editor of Gleichheit, were prosecuted on May 7, 1880, and ordered before an exceptional court for Anarchistic aspirations. For, so said the court, all aspirations towards a violent upheaval are Anarchistic. The goals of Social-Democracy could not be reached without a violent upheaval, therefore their aspirations must be considered as synonymous with those of the Anarchists. It is clear that a court capable of such logic would not hesitate at any sentence. On June 27 1880 Adler was sentenced to four months’ severe arrest, intensified by one fast-day in every month – a measure which is only used in dealing with the most hardened criminals. It was the most futile revenge against Adler for having made use of the trial to denounce the Exceptional Court of Justice – one of the most rascally institutions that Austria has ever produced."

In 1888 helped form the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) and served as chairman. He also published the party newspaper, Arbeiter-Zeitung. During this period he was arrested and spent nine months in prison. On his release Adler lived in Switzerland where he spent time with Friedrich Engels, August Bebel and Karl Liebknecht. He was also a strong supporter of the Second International.

Adler played an important role in organizing strike in Vienna. As Karl Kautsky pointed out: "That already became evident in 1889, a year which brought a new burst of life in the trade unions, and a great strike movement. Here, too, Adler’s wisdom, energy, ands expert knowledge constituted him a leading spirit. Already the first great strike of the new era – that of the tram-drivers, from April 4 to 27, 1889 – gave him the opportunity of winning his spurs. That this strike, which threw all Vienna into confusion, at last ended by a recognition of the drivers’ demands, was to a great extent due to Adler’s advice, and the funds that he raised for its support."

Friedrich Engels argued: "During the last few days we are all full of the strike. Excuse on that account the shortness of my letter. I am writing in great haste, and my thoughts are more in the street than at the desk. I live vis-a-vis to a cavalry-barrack – just now the cavalry have been called out. It is a Trafalgar Square affair in miniature which we are experiencing here, only here I am, of course, more in the thick of it. Adler has behaved in a manner worthy of all admiration. I have more respect for him every day."

The journalist, Konrad Heiden, has pointed out: "The Social-Democratic organisation had not only to be built up anew, but to be filled with a new spirit which should do away with the difference between radicals and moderates. But they were still divided by the memory of personal quarrels as yet hardly overcome, and to find and become masters of the new thought was a difficult task for the theoretically quite unschooled masses. In this situation Victor Adler entered the field. It was at the time of the deepest depression of the Austrian proletariat that he took his place in their ranks as a neutral mediator who had taken no part in the internal quarrels, and whose name was, therefore, not connected with any bitter memories for either side; but also as a teacher."

In 1891 Karl Lueger helped to establish the Christian Social Party (CSP). Deeply influenced by the philosophy of the Catholic social reformer, Karl von Vogelsang, who had died the previous year. There were many priests in the party, which attracted many votes from the tradition-bound rural population. It was seen as a rival to Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) that was portrayed by Lueger as an anti-religious party.

After the 1895 elections for the Vienna's City Council the Christian Social Party took political power from the ruling Liberal Party. Lueger was selected to became mayor of Vienna but this was overruled by Emperor Franz Joseph who considered him a dangerous revolutionary. After personal intercession by Pope Leo XIII his election was finally sanctioned in 1897.

Lueger made several speeches where he pointed out that Adler and other leaders of the SDAP were Jews. In a speech in 1899, Lueger claimed that Jews were exercising a "terrorism, worse than which cannot be imagined" over the masses through the control of capital and the press. It was a matter for him, he continued, "of liberating the Christian people from the domination of Jewry". On other occasions he described the Jews as "beasts of prey in human form". Lueger added that anti-semitism would "perish when the last Jew perished".

On his return to Austria Victor Adler led the campaign in favour of universal suffrage. This was achieved following a General Strike in 1907. In the first elections the SDAP won 87 seats, coming second to the Christian Social Party (CSP). The SDAP became the largest party in Austrian Parliament in 1911. Adolf Hitler was a strong opponent of Adler. Ian Kershaw, the author of Hitler 1889-1936 (1998) has argued: "The rise of Lueger's Christian Social Party made a deep impression on Hitler... he came increasingly to admire Lueger.... With a heady brew of populist rhetoric and accomplished rabble-rousing. Lueger soldered together an appeal to Catholic piety and the economic self-interest of the German-speaking lower-middle classes who felt threatened by the forces of international capitalism, Marxist Social Democracy, and Slav nationalism... The vehicle used to whip up the support of the disparate targets of his agitation was anti-semitism, sharply on the rise among artisanal groups suffering economic downturns and only too ready to vent their resentment both on Jewish financiers and on the growing number of Galician back-street hawkers and pedlars."

Adolf Hitler argued in Mein Kampf (1925) that it was Lueger who helped develop his anti-semitic views: "Dr. Karl Lueger and the Christian Social Party. When I arrived in Vienna, I was hostile to both of them. The man and the movement seemed reactionary in my eyes. My common sense of justice, however, forced me to change this judgment in proportion as I had occasion to become acquainted with the man and his work; and slowly my fair judgment turned to unconcealed admiration... For a few hellers I bought the first anti-Semitic pamphlets of my life.... Wherever I went, I began to see Jews, and the more I saw, the more sharply they became distinguished in my eyes from the rest of humanity. Particularly the Inner City and the districts north of the Danube Canal swarmed with a people which even outwardly had lost all resemblance to Germans. And whatever doubts I may still have nourished were finally dispelled by the attitude of a portion of the Jews themselves."

Hitler goes onto argue: "By their very exterior you could tell that these were no lovers of water, and, to your distress, you often knew it with your eyes closed. Later I often grew sick to my stomach from the smell of these caftan-wearers. Added to this, there was their unclean dress and their generally un-heroic appearance. All this could scarcely be called very attractive; but it became positively repulsive when, in addition to their physical uncleanliness, you discovered the moral stains on this 'chosen people.' In a short time I was made more thoughtful than ever by my slowly rising insight into the type of activity carried on by the Jews in certain fields. Was there any form of filth or profligacy, particularly in cultural life, without at least one Jew involved in it? If you cut even cautiously into such an abscess, you found, like a maggot in a rotting body, often dazzled by the sudden light - a kike! What had to be reckoned heavily against the Jews in my eyes was when I became acquainted with their activity in the press, art, literature, and the theater."

On 28th June, 1914, the heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in Sarajevo. Emperor Franz Joseph accepted the advice given by his foreign minister, Leopold von Berchtold, that Austria-Hungary should declare war on Serbia. Leon Trotsky explained the response by the socialists in Austria to the war: "What attitude toward the war did I find in the leading circles of Austrian Social Democrats? Some were quite obviously pleased with it... These were really nationalists, barely disguised under the veneer of a socialist culture which was now melting away as fast as it could.... Others, with Victor Adler at their head, regarded the war as an external catastrophe which they had to put up with. Their passive waiting, however, only served as a cover for the active nationalist wing."

On the outbreak of the First World War, Emperor Josef allowed the military to take over the running of the country. President Karl von Stürgkh imposed strict press censorship and restricted the right of assembly and showed his contempt for democracy by converting the Reichsrat into a hospital.

Victor's son, Friedrich Adler, was a strong opponent of the war. On 21st October, 1916, Adler shot and killed President Stürgkh in the dining room of the Hotel Meißl und Schadn. Adler was sentenced to death, a sentence which was commuted to 18 years imprisonment by Emperor Karl.

Victor Adler died in Vienna on 11th November 1918.

Primary Sources

(1) Karl Kautsky, The Social Democrat (July 1912)

On June 24 it was sixty years since Victor Adler first saw the light. A strange coincidence gives this date a double significance for me. For almost on the same day I celebrate the 30th anniversary of the occasion when I came into that personal relationship with Adler which was destined to ripen into a bond of friendship for life.

Born in the same town – Prague; studying in the same town – Vienna; living in similar social circles, only separated by a slight difference in age, fired with the same revolutionary fervour, the same love for the proletariat, we had still required three decades to find each other. Both Austrians, we were both national enthusiasts to the same extent, but it was just this that led us into opposite camps: him into the German, me into the Czech. And from thence my road to Socialism was shorter than his, although interest in the Socialist movement began at an earlier age with Adler than with me, and he occupied himself sooner with social ideas...

The hard times during the first years of the Anti-Socialist law constituted the decisive moment in Adler’s life. When I made his acquaintance in 1882 he was not yet an active Social-Democrat though already full of theoretical interest in Social-Democracy.

Our first meeting was only casual. After the publication of my book on the increase of population, I had been engaged at Zurich in 1880-1881, in the Hochberg undertakings and the “Soziall democrat.” The following year I conceived the plan of starting the “Neue Zeit,” and for this purpose stayed some time at Vienna. There I met Adler, and found him to be a clever man rich in knowledge, with great sympathy for our Cause, a man with whom it was a pleasure for me to associate. But I made no attempts to get him to throw in his lot altogether with us. I knew he would come of his own accord if he were really of the fighting nature suitable to our movement, as soon as his studies brought him to a clear conception of Socialism. And he did come. He would probably have entered our ranks even sooner than he did had Austrian Socialism in the early ‘eighties presented a more attractive picture. Until 1866 Austria, had been merely a part of Germany. The Austrian Labour movement remained intellectually a part of that of Germany till 1878. And when the Social-Democracy of Germany appeared to foreign observers to surrender without resistance to the tricks of the Anti-Socialist law in that Empire, the intellectual foundations of Austrian Social-Democracy broke down also. The mass of Austrian proletarians, especially in Vienna, lost confidence in their former pattern, therefore those who criticised it won all the more respect and applause the more scathing their criticism. They went further and further with Most and his emissaries in the direction of Anarchism. This development was accelerated by the rise of the agents-provocateurs, who had met with great success since the inauguration of the Anti-Socialist law in Germany. With the power of the police increased also, the police instigation of crime, at first political and afterwards also common crime .... Nowhere did this system find a more favourable breeding-ground than in Austria, – the officials as its promoters and the proletarians as its victims. An opposition to it did indeed arise in the Party, but it was only strong enough to cause a split in the ranks, not to constitute a defence against Anarchism and the agents-provocateurs. The “moderates” constituted a minority as against the “radicals.”

Under these conditions it would have been difficult for Adler to work fruitfully in our Party. He, therefore, first sought to help the proletariat not as a politician but as a doctor. In this capacity he used to write for the Party Press. When I brought out the “Neue Zeit,” in 1883, one of our first articles was by Adler on Industrial Diseases. ...”

The agents-provocateurs at last succeeded in finding excuses for the forcible destruction of the whole Labour movement. In consequence of the outrages of Kammerer, Stellmacher, and others, the Government, in 1884, laid Vienna under an exceptional law, and the Provinces, especially Bohemia, under Russian conditions, without any actual exceptional legislation. Some of the proletarian organisations were forcibly dissolved, others dissolved themselves voluntarily, to avoid the confiscation of their funds. Both “moderates” and “radicals” were hit hard. By 1885 there was actually no longer any Socialist organisation in Austria.

Not only were the organisations destroyed, but there disappeared with them all the illusions which had led to the split – the illusion that nothing but one forcible upheaval was required in order to throw capitalist society on to the rubbish-heap.

The Social-Democratic organisation had not only to be built up anew, but to be filled with a new spirit which should do away with the difference between “radicals” and “moderates.” But they were still divided by the memory of personal quarrels as yet hardly overcome, and to find and become masters of the new thought was a difficult task for the theoretically quite unschooled masses.

In this situation Victor Adler entered the field. It was at the time of the deepest depression of the Austrian proletariat that he took his place in their ranks as a neutral mediator who had taken no part in the internal quarrels, and whose name was, therefore, not connected with any bitter memories for either side; but also as a teacher. If I entered the Party ten years before him, I did so, as a seeker and learner. He had already gone through this stage, outside the Party, and – when he carne to it he was already equipped with the whole armoury of Marxianism. From the first day of his membership he was theoretically far ahead of his comrades.

As mediator and as teacher he soon acquired influence over both sections, all the more because he did not seek it, but only placed his strength at his comrades’ disposal. At the end of 1886 he had already got so far as to be able to publish a weekly paper Gleichheit (Equality), which both parties recognised as their organ. This recognition, indeed, would not, in view of the deplorable state of the Party at that tine, have sufficed to keep the paper going had not Adler given his fortune as well as his personal service for it.

Never before had the authorities been attacked with so much, boldness and vigour by our Party in Austria as now by Adler. Till then police and courts had arrogated to themselves the right to determine the boundaries beyond which the rights of the Press and public assembly might not go. Adler set himself and the Party the contrary task – namely, to educate the police and the courts, and see that they did not pass their limits. A difficult task. But his courage and persistence succeeded at last in giving the proletariat, who up till then were really without any rights whatever, a new actual right, which not only fulfilled th nominal right, but even extended it in practice on certain points.

Soon the confusion, the depression, the mutual mistrust among the members of the Party disappeared. With renewed strength they set to work to found a new party organisation. A Party Congress was convened, for which Adler drew up a programme which in every respect was excellent: the first Marxian Party programme in the German tongue. That is, strictly speaking; the first was that which I laid before the Brünner Conference, and which it accepted. But mine was not original. The convener of the Conference had, indeed, decided that I was to work out a programme, but had forgotten to tell me! I only heard of it at the Congress itself, just before I was to present it. What was to done? I saved the situation by translating the French program prepared, under Marx’s surveillance in 1880, which was familiar to me, making a few alterations to adapt it to Austrian condition This programme was certainly very Marxian, but not suitable for Germany. The first programme composed in the German language was that written by Adler, and accepted at Hainfeld in 1888 – three years before the Erfurt Programme.

The Hainfeld Conference was the starting-point of the new Social-Democracy of Austria, It laid the foundation on which it has developed so splendidly. No one took a greater part in the preparations and arrangements than Victor Adler.

But he was not satisfied with being a theoretical teacher, a theoretical fighter and organiser. He wanted to be at home with, and take part in, all branches of the proletarian movement. He not only studied them all theoretically, but also took an active part. He knew how to fit them all into their right connection with the whole social development of our time, and how to interest himself in all their details...

Adler’s activity was recognised with joy by the great majority of comrades from the beginning – recognised, took though on no account with joy, by our opponents. In their own way, of course. The tram-drivers’ strike gave them the first occasion. For incitement, abuse of the authorities, and praising illegal actions, Adler and Bretschneider, the responsible editor of “Gleichheit,” were prosecuted on May 7, 1880, and ordered before an exceptional court for Anarchistic aspirations. For, so said the court, all aspirations towards a violent upheaval are Anarchistic. The goals of Social-Democracy could not be reached without a violent upheaval, therefore their aspirations must be considered as synonymous with those of the Anarchists. It is clear that a court capable of such logic would not hesitate at any sentence. On June 27 1880 Adler was sentenced to four months’ severe arrest, intensified by one fast-day in every month – a measure which is only used in dealing with the most hardened criminals. It was the most futile revenge against Adler for having made use of the trial to denounce the Exceptional Court of Justice – one of the most rascally institutions that Austria has ever produced.

Adler’s appeal was rejected on December 7. Before he entered upon his imprisonment, he prepared the propaganda for the May-Day festival.

In July the Paris International Congress had been held, which Adler at once attracted general notice. From the time of this first meeting of the New International, he was numbered among its recognised leaders. The decision of the Congress most pregnant with results was that which fixed an international celebration for May 1 without going into details as to the form it should take. That was left to each country to decide for itself.

I well remember a conversation with Adler about what form the demonstration should take in Austria. He came to the conclusion that a general abstention from work should he aimed at, and in Vienna, a procession to the Prater. I shook my head sceptically at these plans; the proletariat of Vienna, enslaved by the exceptional law, and whose organisation was but in its preliminary stages, did not seem to me ready for this trial of strength. But at last I too became infected with the enthusiasm of Adler, who was usually so sober in his judgment. And he managed to fire the whole Party with this enthusiasm, and the success proved that this had been no mere intoxication. The Vienna May-Day turned out the most brilliant and imposing celebration among those of the whole world, ands it has remained so ever since. All at once the self-respect of the Austrian proletariat, and its reputation among its opponents, as well as among the comrades in other countries became immeasurably increased. The Social-Democracy of Austria, hitherto a pitiable dwarf, appeared from that time onwards as a feared and respected giant.

And how this giant has grown since then!

That is to be ascribed to a great extent to the comprehension which Austria showed in the early days for modern mass-action.

The example of the Belgian mass-strike of 1893 awakened the liveliest echo in Austria, then in the throes of the most violent suffrage campaign. The idea of the mass-strike caught on, and set the Party on fire. Victor Adler was one of the first to study the nature of this weapon, and determine the rules for its use. He did not belong to the older comrades, still numerous at that time who simply repudiated the mass-strike or even refused to discuss it; but he kept cool, and did not let himself be carried away by the easily excited hot-heads who, always ready for a fight, thought a weapon that had once been successfully used was equally good everywhere and under all circumstances.

At the Vienna Conference of 1894 he introduced a resolution which laid down:-

“The Conference declares that it will fight for the suffrage with all the weapons at the disposal of the working class. To these belong, as well as the already used methods of propaganda and organisation, also the mass-strike. The Party representatives and the representatives of the organisation groups are instructed to make all arrangements, so that if the persistency of the Government and of the bourgeois parties should drive the proletariat to extremes, the mass-strike can be ordered at a suitable time, as the last means.”

Thus he formulated the basis on which the struggle for the suffrage has been carried on ever since. The idea of the mass-strike, the consciousness of not having to stand defenceless if the worst should come to the worst, but of being possessed of a sharp weapon, has vivified and strengthened the confidence and the fighting spirit of the masses to a high degree. But at the same time the leaders of the Party took care that this last and extremest weapon should not be used prematurely or at the wrong time, and hindered every agitation which might have the effect of binding the Party beforehand to use the weapon at any particular moment. They determined the goal and the tactical principles, but took care to reserve the fullest freedom to use in every situation such measures as are best suited to it.

By a wise and determined use of these tactics the Austrian Social-Democracy has attained its enormous triumphs in the suffrage-struggle, has become possessed, of general and equal suffrage for men in a fight which has increased its numbers by tenfold. This was not indeed taken by storm, as the hot-heads of 1894 hoped, but in a long, persistent struggle, lasting for over a decade.

This was not possible without Adler’s often being obliged to put on the brake, to impress upon those who were rushing forward the necessity for a sober investigation of the conditions. A hard and ungrateful task. In many cases Adler managed to solve the difficulty successfully without paying for it in love and respect. That was only possible because everyone in the Party knew that if he put on the brake it was not from timidity. In times of danger Victor Adler has ever been found in the front ranks. Everyone felt that it was only his thorough and sober knowledge of the strength of the various factors that determined Adler in some situations to play the part of a warning voice, instead of urging forward.

He, and, we with him, may now look back upon his work with satisfaction, and with joyful expectancy into the future, even though there falls across the day of his triumph the dark shadow of a phenomenon which inflicts severe wounds on our Party, which for a time seemed even to menace it at its roots, and threatened to destroy just what had always been the most precious thing to Victor Adler, for which he had specially cared and, worked – the unity of the Party.

The great danger was that of a national struggle between the Czech and German proletariat. That would have entirely ruined the Social-Democracy of Austria for years to come. This danger may now be considered as overcome. Never among the German proletariat has it come to a fight against Czech proletarians as such. Neither has the Czech proletariat in its totality taken up the fight against the German Social-Democracy... Thus Victor Adler may have good hope of seeing his greatest longing – for the unity of the proletarian army – again realised in a full measure.

This will be owing to a large extent to the fact that all the class-conscious, international-feeling proletarians of Austria see in him their leader, in whom they have the most trust – all proletarians, Czechs, Poles, Italians, no less than Germans.

There are few so able to adapt themselves to the peculiarities of foreign nations, and to understand them, as Victor Adler. A specially important quality for a politician of Austria, and not very common there, where every nation watches jealously over the preservation of its own peculiarities.

This international understanding of Adler’s is due to a quality which also in other ways greatly increases his usefulness in the. Party: his gift of understanding people and adapting himself to them. Few understand as he does how to work upon the soul of the masses, as of the individual. To this is largely due the special character of the influence.

He is just as much a master of the pen as of the spoken word, and his scientific knowledge would enable him to elaborate his ideas in learned books. But this way of reaching the world has never attracted him; so far he is one of the few thinkers in our paper age who have not published a book. He prefers the old Socratic method of direct personal influence on those who for one or the other reason appear to him to carry weight. This influence goes deeper than most books. And it is, as becomes Adler’s many-sided interests, of the most variegated kind. If one looks at any of the younger leaders of our Party in Austria, they have nearly, all been through Adler’s school : the theoreticians and the journalists, the parliamentarians and the trade unionists, as well as those at the head of the co-operatives. He has given himself to each of them, encouraged each, helped each to begin his work, and therefore he is bound to the mass of comrades who are active in’ the service of the Party, not only by a mutual goal and comradeship in arms, but also by the most affectionate personal friendship.,

This is clearly seen on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. His life for decades has been spent for the life of the Party. The celebration of his work is at the same time a celebration of the conquests and triumphs of Social-Democracy. But it also bears the character of a family festival – a festival of the great family of the Austrian Party, whose patriarch Victor Adler has become; not by virtue of his years by a long way, but long since by virtue of the trust and the love which all those feel for him who have felt the breath of his spirit.

(2) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1925)

At the age of seventeen the word "Marxism" was as yet little known to me, while 'Social Democracy' and socialism seemed to me identical concepts. Here again it required the fist of Fate to open my eyes to this unprecedented betrayal of the peoples.

Up to that time I had known the Social Democratic Party only as an onlooker at a few mass demonstrations, without possessing even the slightest insight into the mentality of its adherents or the nature of its doctrine; but now, at one stroke, I came into contact with the products of its education and philosophy. And in a few months I obtained what might otherwise have required decades: an understanding of a pestilential whore, cloaking herself as social virtue and brotherly love, from which I hope humanity will rid this earth with the greatest dispatch, since otherwise the earth might well become rid of humanity.

My first encounter with the Social Democrats occurred during my employment as a building worker. From the very beginning it was none too pleasant. My clothing was still more or less in order, my speech cultivated, and my manner reserved. I was still so busy with my own destiny that I could not concern myself much with the people around me. I looked for work only to avoid starvation, only to obtain an opportunity of continuing my education, though ever so slowly. Perhaps I would not have concerned myself at all with my new environment if on the third or fourth day an event had not taken place which forced me at once to take a position. I was asked to join the organization.

My knowledge of trade-union organization was at that time practically non-existent. I could not have proved that its existence was either beneficial or harmful. When I was told that I had to join, I refused. The reason I gave was that I did not understand the matter, but that I would not let myself be forced into anything. Perhaps my first reason accounts for my not being thrown out at once. They may perhaps have hoped to convert me or break down my resistance in a few days. In any event, they had made a big mistake. At the end of two weeks I could no longer have joined, even if I had wanted to. In these two weeks I came to know the men around me more closely, and no power in the world could have moved me to join an organization whose members had meanwhile come to appear to me in so unfavorable a light....

On such days of reflection and cogitation, I pondered with anxious concern on the masses of those no longer belonging to their people and saw them swelling to the proportions of a menacing army. With what changed feeling I now gazed at the endless columns of a mass demonstration of Viennese workers that took place one day as they marched past four abreast! For neatly two hours I stood there watching with bated breath the gigantic human dragon slowly winding by. In oppressed anxiety, I finally left the place and sauntered homeward. In a tobacco shop on the way I saw the Arbeiter-Zeitung, the central organ of the old Austrian Social Democracy. It was available in a cheap people's cafe, to which I often went to read newspapers; but up to that time I had not been able to bring myself to spend more than two minutes on the miserable sheet, whose whole tone affected me like moral vitriol. Depressed by the demonstration, I was driven on by an inner voice to buy the sheet and read it carefully. That evening I did so, fighting down the fury that rose up in me from time to time at this concentrated solution of lies. More than any theoretical literature, my daily reading of the Social Democratic press enabled me to study the inner nature of these thought-processes. For what a difference between the glittering phrases about freedom, beauty, and dignity in the theoretical literature, the delusive welter of words seemingly expressing the most profound and laborious wisdom, the loathsome humanitarian morality - all this written with the incredible gall that comes with prophetic certainty - and the brutal daily press, shunning no villainy, employing every means of slander, lying with a virtuosity that would bend iron beams, all in the name of this gospel of a new humanity. The one is addressed to the simpletons of the middle, not to mention the upper, educated, 'classes,' the other to the masses. For me immersion in the literature and press of this doctrine and organization meant finding my way back to my own people. What had seemed to me an unbridgable gulf became the source of a greater love than ever before. Only a fool can behold the work of this villainous poisoner and still condemn the victim. The more independent I made myself in the next few years the clearer grew my perspective, hence my insight into the inner causes of the Social Democratic successes. I now understood the significance of the brutal demand that I read only Red papers, attend only Red meetings, read only Red books, etc. With plastic clarity I saw before my eyes the inevitable result of this doctrine of intolerance. The psyche of the great masses is not receptive to anything that is half-hearted and weak. Like the woman, whose psychic state is determined less by grounds of abstract reason than by an indefinable emotional longing for a force which will complement her nature, and who, consequently, would rather bow to a strong man than dominate a weakling, likewise the masses love a commander more than a petitioner and feel inwardly more satisfied by a doctrine, tolerating no other beside itself, than by the granting of liberalistic freedom with which, as a rule, they can do little, and are prone to feel that they have been abandoned. They are equally unaware of their shameless spiritual terrorization and the hideous abuse of their human freedom, for they absolutely fail to suspect the inner insanity of the whole doctrine. All they see is the ruthless force and brutality of its calculated manifestations, to which they always submit in the end. If Social Democracy is opposed by a doctrine of greater truth, but equal brutality of methods, the latter will conquer, though this may require the bitterest struggle...

By the turn of the century, the trade-union movement had ceased to serve its former function. From year to year it had entered more and more into the sphere of Social Democratic politics and finally had no use except as a battering-ram in the class struggle. Its purpose was to cause the collapse of the whole arduously constructed economic edifice by persistent blows, thus, the more easily, after removing its economic foundations, to prepare the same lot for the edifice of state.

Less and less attention was paid to defending the real needs of the working class, and finally political expediency made it seem undesirable to relieve the social or cultural miseries of the broad masses at all, for otherwise there was a risk that these masses, satisfied in their desires could no longer be used forever as docile shock-troops.

The leaders of the class struggle looked on this development with such dark foreboding and dread that in the end they rejected any really beneficial social betterment out of hand, and actually attacked it with the greatest determination.

And they were never at a loss for an explanation of a line of behavior which seemed so inexplicable.By screwing the demands higher and higher, they made their possible fulfillment seem so trivial and unimportant that they were able at all times to tell the masses that they were dealing with nothing but a diabolical attempt to weaken, if possible in fact to paralyze, the offensive power of the working class in the cheapest way, by such a ridiculous satisfaction of the most elementary rights.

(3) Konrad Heiden, Der Führer – Hitler's Rise to Power (1944)

There were in particular two secrets of success which Hitler thought he had learned from him: Lueger put the chief emphasis "on the winning of classes whose existence is threatened", because only such classes carry on the political struggle with passion; secondly, he took pains in "inclining powerful existing institutions to his use". In Lueger's case this was the all-powerful Catholic Church; in another case it might have been the German Army or the Bank of England; and no one will ever have any success in politics who overlooks this obvious fact.

But whatever Hitler learned or thought he had learned from his model, Lueger, he learned far more from his opponent. And this opponent, whom he combated from the profound hatred of his soul, is and remains plain ordinary work. Organized, it calls itself labour movement, trade union, Socialist Party. And, or so it seems to him, Jews are always the leaders.

The relatively high percentage of Jews in the leadership of the Socialist parties on the European continent cannot be denied. The intellectual of the bourgeois era had not yet discovered the workers, and if the workers wanted to have leaders with university education, often only the Jewish intellectual remained - the type which might have liked to become a judge or Government official, but in Germany, Austria, or Russia simply could not. Yet, though many Socialist leaders are Jews, only few Jews are Socialist leaders. To call the mass of modern Jewry Socialist, let alone revolutionary, is a bad propaganda joke. The imaginary Jew portrayed in The Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion ostensibly wants to bend the nations to his will by revolutionary mass uprisings; the real Jewish Socialist of France, Germany, and Italy, however, is an intellectual who had to rebel against his own Jewish family and his own social class before he could come to the workers.

Karl Marx, the prototype of the supposed Jewish labour leader, came of a baptized Christian family, and his own relation with Judaism can only be characterized as anti-Semitism; for under Jews he understood the sharply anti-Socialist, yes, anti-political Jewish masses of Western Europe, whom as a good Socialist he coldly despised.

The Jewish Socialist leaders of Austria in Hitler's youth were for the most part a type with academic education, and their predominant motive was just what Hitler at an early age so profoundly despised, "a morality of pity", an enthusiastic faith in the oppressed and in the trampled human values within them. The Jewish Socialist, as a rule, has abandoned the religion of his fathers, and consequently is a strong believer in the religion of human rights; this type, idealistic and impractical even in the choice of his own career, was often unequal to the test of practical politics and was pushed aside by more robust, more worldly, less sentimental leaders arising from the non-Jewish masses. An historic example of this change in the top Socialist leadership occurred in Soviet Russia between 1926 and 1937, when the largely Jewish leaders of the revolutionary period (Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev) were bloodily shoved aside by a dominantly non-Jewish class (Stalin, Voroshilov, etc.); the last great example of the humanitarian but impractical Socialist leader of Jewish origin was Leon Blum in France.It was in the world of workers, as he explicitly tells us, that Adolf Hitler encountered the Jews. The few bourgeois Jews. The few bourgeois Jews in the home city did not attract his attention; if we believe his own words, the Jewish `money domination' flayed by Wagner made no impression upon him at that time. But he did notice the proletarian and sub-proletarian figures from the Vienna slums, and they repelled him; he felt them to be foreign - just as he felt the non-Jewish workers to be foreign. With amazing indifference he reports that he could not stand up against either of them in political debate; he admits that the workers knew more than he did, that the Jews were more adept at discussion. He goes on to relate how he looked into this uncanny labour movement more closely, and to his great amazement discovered large numbers of Jews at its head. The great light dawned on him; suddenly the "Jewish question" became clear. If we subject his own account to psychological analysis, the result is rather surprising: the labour movement did not repel him because it was led by Jews; the Jews repelled him because they led the labour movement. For him this inference was logical. To lead this broken, degenerate mass, dehumanized by overwork, was a thankless task. No one would do it unless impelled by a secret, immensely alluring purpose; the young artist-prince simply did not believe in the morality of pity of which these Jewish leaders publicly spoke so much; there is no such thing, he knew people better - particularly he knew himself. The secret purpose could only be a selfish one - whether mere good living or world domination, remained for the moment a mystery. But one thing is certain: it was not Rothschild, the capitalist, but Karl Marx, the Socialist, who kindled Adolf Hitler's anti-Semitism.

No justice, no equal rights for all! One of Hitler's most characteristic reproaches to the labour movement is that in Austria it had fought for equal rights for all - to the detriment of the master race chosen by God. At the beginning of the century the Austrian parliament was organized on the basis of a suffrage system which for practical purposes disenfranchised the poor. This assured the more prosperous German population a position of dominance. By a general strike the Social Democrats put an end to this scandal, and twenty years later Hitler still reproached them for it: "By the fault of the Social Democracy, the Austrian State became deathly sick. Through the Social Democracy universal suffrage was introduced in Austria and the German majority was broken in the Reichsrat" - the Austrian parliament.

The power and strategy of this movement made an enormous impression on the young Adolf Hitler, despite all his revulsion. An impressive model for the power-hungry - for the young artist-prince in beggar's garb will never let anyone convince him that the labour movement owed its existence to anything but the lust for power of Jewish wire-pullers. A new labour party would have to be founded, he told Hanisch, and the organization would have to be copied from the Social Democrats; but the best slogans should be taken from all parties, for the end justifies the means. Adolf Hitler saw with admiration how an unscrupulous intelligence can play the masses: for him this was true of the Austrian Social Democrats as well as their opponent, Kurt Lueger.