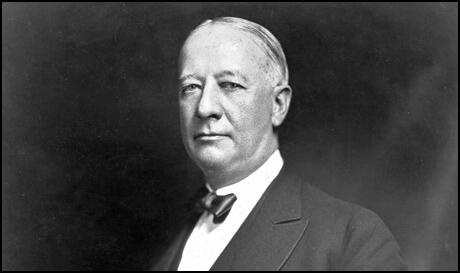

Al Smith

Alfred (Al) Smith was born in New York City on 30th December, 1873. After a brief formal education he found employment in the Fulton fish market. He become a member of the Democratic Party and in 1903 was elected to the state assembly.

In 1911 he became a member of a commission investigating factory conditions. Shocked by what he found he became associated with those politicians such as Robert Wagner and Frances Perkins, who were attempting to persuade the government to pass legislation to protect industrial workers. A popular politician, he served as speaker of the New York Assembly (1913), sheriff of New York County (1915-17) and president of the Board of Aldermen of New York (1917).

Smith was elected governor of New York for four terms (1919-20, 1923-28). As governor he attempted to bring an end to child labour, improve factory laws, housing and the care of the mentally ill. Smith was a popular figure in the Democratic Party and in 1928 Franklin D. Roosevelt returned to politics in an attempt to help him become president. Smith was the first Roman Catholic to be a serious candidate for the presidency. It is believed that his religion, combined with his opposition to Prohibition, led to his defeat by the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover.

In 1932 Smith supported his old friend, Franklin D. Roosevelt, in his campaign to become president. However, in the 1936 and 1940 elections, Smith supported the Republican presidential candidates.

Alfred Smith died in New York City on 4th October, 1944.

Primary Sources

(1) Frances Perkins wrote about Al Smith and his attempts to become president in her book, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946)

People who had willingly voted for Al Smith as Governor time after time turned tail when it came to voting for him for President. No governor in New York State had commanded such respect and affection as Al Smith, but too many people were frightened of the idea, so hard to combat, so unreal in its conception, that the Church of Rome might take control of the United States if he were made President.

(2) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

Oratory was an art in those days and I would circulate from corner to corner. I remember nothing of what was said, however, until the presidential campaign of 1928, when Al Smith became my first political hero. The fact that Smith was the son of immigrants, had been born on the East Side and was now the target of religious bigotry, made him attractive. By this time I had become a foe of Prohibition and an advocate of evolution. (As I followed the Tennessee trial over the advocacy of evolution, it never occurred to me, gf course, that one day I would figure in a trial over the right to advocate revolution.)

Radio was used on a wide scale for the first time in that 1928 campaign and I remember the fine scorn with which Smith ridiculed the GOP slogans of "Two Chickens In Every Pot" and "Two Cars in Every Garage," and the way he pronounced "raddio." My disappointment over Smith's defeat was great and I attributed it to bigotry. Undoubtedly this was an important factor, but I didn't understand then that Smith had been defeated mainly by the very prosperity which was the butt of his sarcasm.

(3) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

That presidential election with Governor Smith, a Jeffersonian Democratic politician, running to defeat against Hoover, an engineer in business, seemed to mark the end of a period, my period, and perhaps of a culture, the moral culture. Hoover was the Hamiltonian, who had no democracy in him, none, neither political nor economic. He has shown no sense of the perception that privileges are a cause of our social trouble. He is a moralist in that. He believes in the ownership and management by business men of all business, including land and natural resources, transportation, power, light. Good business is all the good we need. Politics was the only evil, and he has no sense of politics. When he came home from his years and years of professional service in foreign lands, he did not know or care whether he was a Democrat or a Republican; he was a candidate and won some votes for the nomination for president at a Democratic convention. He stood four years later as the Republican candidate of and for business against an able, successful Democrat who was a philosophic, political democrat. And the people believed, as they voted, with Hoover. Food, shelter, and clothing, plus the car, the radio-prosperity interested them more than any old American principles, which were all on the Democratic side with Smith. I went through that campaign, sensitive, interested, non-partisan. What little I said was in the Jeffersonian tradition, but I was watching to report, not playing to win. I can assert that everybody was for business; even the Democrats who voted for Smith, were for good business, of course; they, too, expected Smith to carry on the good times and favor business. It seems to me that there are many more Republicans in this country than voted for Hoover, that our southern Democrats, party-bound by their traditions, are unconscious Republicans who only think that they are Democrats, who don't know that they are Republicans. In California, where I was living, there were no politics or principles at all. It was all business. In brief, that was an economic election which sent to the White House Herbert Hoover to do what he is trying to do: to represent business openly, as Coolidge and other presidents had covertly.