On this day on 24th January

On this day in 1749 Charles James Fox, the son of the Henry Fox, a leading politician in the House of Commons, was born on 24th January, 1749. After being educated at Eton and Oxford University, Fox was elected to represent Midhurst in the Commons when he was only nineteen.

At the age of twenty-one, Fox was appointed by Frederick North, the prime minister, as the Junior Lord of the Admiralty. In December 1772 Fox became Lord of the Treasury but was dismissed by in February 1774 after criticising the influential artist and journalist, Henry Woodfall.

Out of office, Charles Fox opposed North's policy towards America. He denounced the taxation of the Americans without their consent. When war broke out Fox called for a negotiated peace.

In April 1780 John Cartwright helped establish the Society for Constitutional Information. Other members included John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Gales and William Smith. It was an organisation of social reformers, many of whom were drawn from the rational dissenting community, dedicated to publishing political tracts aimed at educating fellow citizens on their lost ancient liberties. It promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform.

Charles Fox became convinced by Cartwright's arguments. He advocated the disfranchisement of rotten and pocket boroughs and the redistribution of these seats to the fast growing industrial towns. When Lord Frederick North's government fell in March 1782, Fox became Foreign Secretary in Rockingham's Whig government. Fox left the government in July 1782, on the death of the Marquis of Rockingham as he was unwilling to serve under the new prime minister, Lord Sherburne. Sherburne appointed the twenty-three year old William Pitt as his Chanchellor of the Exchequer. Pitt had been a close political friend of Fox and after this the two men became bitter enemies.

In 1787 Thomas Clarkson, William Dillwyn and Granville Sharp formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although Sharp and Clarkson were both Anglicans, nine out of the twelve members on the committee, were Quakers. This included John Barton (1755-1789); George Harrison (1747-1827); Samuel Hoare Jr. (1751-1825); Joseph Hooper (1732-1789); John Lloyd (1750-1811); Joseph Woods (1738-1812); James Phillips (1745-1799) and Richard Phillips (1756-1836). Influential figures such as Charles Fox, John Wesley, Josiah Wedgwood, James Ramsay, and William Smith gave their support to the campaign. Clarkson was appointed secretary, Sharp as chairman and Hoare as treasurer.

Clarkson approached another sympathiser, Charles Middleton, the MP for Rochester, to represent the group in the House of Commons. He rejected the idea and instead suggested the name of William Wilberforce, who "not only displayed very superior talents of great eloquence, but was a decided and powerful advocate of the cause of truth and virtue." Lady Middleton wrote to Wilberforce who replied: "I feel the great importance of the subject and I think myself unequal to the task allotted to me, but yet I will not positively decline it." Wilberforce's nephew, George Stephen, was surprised by this choice as he considered him a lazy man: "He worked out nothing for himself; he was destitute of system, and desultory in his habits; he depended on others for information, and he required an intellectual walking stick."

Fox was unsure of Wilberforce's commitment to the anti-slavery campaign. He wrote to Thomas Walker: "There are many reasons why I am glad (Wilberforce) has undertaken it rather than I, and I think as you do, that I can be very useful in preventing him from betraying the cause, if he should be so inclined, which I own I suspect. Nothing, I think but such a disposition, or a want of judgment scarcely credible, could induce him to throw cold water upon petitions. It is from them and other demonstrations of the opinion without doors that I look for success."

In May 1788, Fox precipitated the first parliamentary debate on the issue. He denounced the "disgraceful traffic" which ought not to be regulated but destroyed. He was supported by Edmund Burke who warned MPs not to let committees of the privy council do their work for them. William Dolben described shipboard horrors of slaves chained hand and foot, stowed like "herrings in a barrel" and stricken with "putrid and fatal disorders" which infected crews as well. With the support of William Pitt, Samuel Whitbread, William Wilberforce, Charles Middleton and William Smith, Dolben put forward a bill to regulate conditions on board slave ships. The bill passed 56 to 5 and received royal assent on 11th July.

When the French Revolution broke out in 1789 Charles Fox was initially enthusiastic describing it as the "greatest event that has happened in the history of the world". He expected the creation of a liberal, constitutional monarchy and was horrified when King Louis XVI was executed. When war broke out between Britain and France in February 1793, Fox criticised the government and called for a negotiated end to the dispute. Although Fox's views were supported by the Radicals, many people regarded him as defeatist and unpatriotic.

In April 1792, Charles Grey joined with a group of Whigs who supported parliamentary reform to form the Friends of the People. Three peers (Lord Porchester, Lord Lauderdale and Lord Buchan) and twenty-eight Whig MPs joined the group. Other leading members included Richard Sheridan, John Cartwright, John Russell, George Tierney, Thomas Erskine and Samuel Whitbread. The main objective of the the society was to obtain "a more equal representation of the people in Parliament" and "to secure to the people a more frequent exercise of their right of electing their representatives". Charles Fox was opposed to the formation of this group as he feared it would lead to a split in the Whig Party. However, by November eighty-seven branches of the Society of Friends had been established in Britain.

Fox disapproved of the ideas of Tom Paine and criticised Rights of Man, however, he consistently opposed measures that attempted to curtail traditional freedoms. He attacked plans to suspend habeas corpus in May 1794 and denounced the trials of Thomas Muir, Thomas Hardy, John Thelwall and John Horne Tooke. Fox also promoted Catholic Emancipation and opposed the slave trade. Fox continued to support parliamentary reform but he rejected the idea of universal suffrage and instead argued for the vote to be given to all male householders.

When Lord Grenville became prime minister in 1806 he appointed Charles James Fox as his Foreign Secretary. Fox began negotiating with the French but was unable to bring an end to the war. After making a passionate speech in favour of the Abolition of the Slave Trade bill in the House of Commons on 10th June 1806, Fox was taken ill. His health deteriorated rapidly and he died three months later on 13th September, 1806.

On this day in 1800 Edwin Chadwick the son of a journalist, John Chadwick, was born in Manchester. His mother died when he was a child. Chadwick's father had progressive political views and encouraged his son to read books by radicals such as Tom Paine and Joseph Priestley.

While studying in London to become a lawyer, Chadwick joined the Unilitarian Society where he met Jeremy Bentham, James Mill, John Stuart Mill, Francis Place, Thomas Southwood Smith and Neil Arnott.

In 1830 Chadwick became Bentham's private secretary and held this post until the philosopher's death in June 1832. Earl Charles Grey, the Prime Minister, set up a Poor Law Commission to examine the working of the poor Law system in Britain. Chadwick was appointed as one of the assistant commissioners responsible for collecting information on the subject. He soon emerged as one of the most important members of the investigation and he was eventually responsible for writing nearly a third of the published report. However, he had problems with his colleagues for being "impatient, judgemental and infamously rude".

In 1833 Chadwick was seconded to another inquiry, the royal commission on factories. "In a matter of a few months (April to July 1833) he drew up the terms of inquiry, directed the taking of evidence (in camera, to the disgust of the ten-hours lobby), and drew up a report which ingeniously recommended an eight-hour day for children under thirteen, complemented by three hours' education, appealing to humanitarian concerns for the young while avoiding the restrictions on adult labour that so horrified employers." As a result of the inquiry Parliament passed the 1833 Factory Act.

The Poor Law report published in 1834, the Commission made several recommendations to Parliament. As a result of the report, the Poor Law Amendment Act was passed. The act stated that: (a) no able-bodied person was to receive money or other help from the Poor Law authorities except in a workhouse; (b) conditions in workhouses were to be made very harsh to discourage people from wanting to receive help; (c) workhouses were to be built in every parish or, if parishes were too small, in unions of parishes; (d) ratepayers in each parish or union had to elect a Board of Guardians to supervise the workhouse, to collect the Poor Rate and to send reports to the Central Poor Law Commission; (e) the three man Central Poor Law Commission would be appointed by the government and would be responsible for supervising the Amendment Act throughout the country.

Thomas Attwood argued that workhouses would become "prisons from the purpose of terrifying applicants from seeking relief". Daniel O'Connell, said that as an Irishman, he would not say much, but he objected to the bill on the grounds that it "did away with personal feelings and connections." William Cobbett warned the legislators in the House of Commons that "they were about to dissolve the bonds of society" and to pass the law would be "a violation of the contract upon which all the real property of the kingdom was held". Cobbett particularly objected to the separation of families, and to workhouse inmates being forced to wear badges or distinctive clothing. Chadwick was blamed for proposing the workhouse system and his biographer Samuel Finer claims he was "the most unpopular single individual in the whole kingdom".

One of the suggestions accepted by the government was that there should be a three man Central Poor Law Commission that would be responsible for supervising the working of the legislation. Chadwick was not appointed as a Commissioner but was offered the post as Secretary, with a promise that he would have the power to make further recommendations on administering the Poor Law. It has been argued that the government was unwilling to appoint Chadwick as a Commissioner as his "station in society was not as would have made it fit that he should be made one of the Commissioners" and would have upset the "jittery landed élite".

Lord John Russell, the home secretary, developed a good relationship with Chadwick and valued his abilities and in October 1836, he appointed Chadwick with two others to a royal commission on rural police with a view to extending the experiment in professional policing initiated in London. Chadwick compiled a report that suggested a national system of police centrally controlled but locally funded.

In 1837, Parliament passed a Registration Act ordering the registration of all births, marriages and deaths that took place in Britain. Parliament also appointed William Farr to collect and publish these statistics. In his first report for the General Register Office, Farr argued that the evidence indicated that unhealthy living conditions were killing thousands of people every year.

Water consumption in towns per head of population remained very low. In most towns the local river, streams or springs, provided people with water to drink. These sources were often contaminated by human waste. The bacteria of certain very lethal infectious diseases, for example, typhoid and cholera, are transmitted through water, it was not only unpleasant to taste but damaging to people's health. As Alexis de Tocqueville pointed out: "The fetid, muddy waters, stained with a thousand colours by the factories they pass, of one of the streams... wander slowly round this refuge of poverty."

In 1839 Edwin Chadwick married Rachel Dawson Kennedy, fifth daughter of John Kennedy, a prominent textile manufacturer in Manchester. It is believed that she brought a substantial dowry, thus relieving slightly Chadwick's recurrent financial worries. The couple moved to Stanhope Street in London, and within the next few years produced Osbert Chadwick (1842–1913), a civil engineer, and Marion Chadwick (1844–1928), who was active in the women's movement. His daughter noted that Chadwick "had a high opinion of animals, children, and women (whose enfranchisement he supported), but did not enjoy close relations with any of them".

The Poor Law Commission became concerned that a high proportion of all poverty had its origins in disease and premature death. Men were unable to work as a result of long-term health problems. A significant proportion of these men died and the Poor Law Guardians were faced with the expense of maintaining the widow and the orphans. The Commission decided to ask three experienced doctors, James P. Kay-Shuttleworth, Thomas Southwood Smith and Neil Arnott, to investigate and report on the sanitary condition of some districts in London.

On receiving details of the doctor's investigation, the Poor Law Commission sent a letter to Lord John Russell, suggesting that if the government spent money on improving sanitation it would reduce the cost of looking after the poor: "In general, all epidemics and all infectious diseases are attended with charges immediate and ultimate on the poor-rates. Labourers are suddenly thrown by infectious disease into a state of destitution for which immediate relief must be given: in the case of death the widow and the children are thrown as paupers on the parish. The amount of burdens thus produced is frequently so great, as to render it good economy on the part of the administrators of the poor laws to incur the charges for preventing the evils, where they are ascribable to physical causes, which there are no other means of removing."

These reports were debated in the House of Lords but it was not until twelve months later that Charles Blomfield, the Bishop of London, suggested that the London surveys should be followed up by a full-scale enquiry into the sanitary condition of the whole nation. Edwin Chadwick was asked to head the investigation. Questionnaires were circulated to all Poor Law guardians, union relieving officers and medical officers. A number of doctors in England and Scotland were asked to prepare special reports on the sanitary conditions in their own towns or countries.

Chadwick's report, The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population, was published in 1842. He argued that slum housing, inefficient sewerage and impure water supplies in industrial towns were causing the unnecessary deaths of about 60,000 people every year: "Of the 43,000 cases of widowhood, and 112,000 cases of orphanage relieved from the poor rates in England and Wales, it appears that the greatest proportion of the deaths of heads of families occurred from... removable causes... The expense of public drainage, of supplies of water laid on in houses, and the removal of all refuse... would be a financial gain.. as it would reduce the cast of sickness and premature death."

Chadwick was a disciple of Jeremy Bentham, the philosopher who questioned the value of all institutions and customs by the test of whether they contributed to "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". Edwin Chadwick claimed that middle-class people lived longer and healthier lives because they could afford to pay to have their sewage removed and to have fresh water piped into their homes. For example, he showed the average age of death for the professional class in Liverpool was 35, whereas it was only 15 for the working-classes.

Edwin Chadwick criticised the private companies that removed sewage and supplied fresh water, arguing that these services should be supplied by public organisations. He pointed out that private companies were only willing to supply these services to those people who could afford them, whereas public organisations could make sure everybody received these services. He argued that the "cost of removing sewage would be reduced to a fraction by carrying it away by suspension in water". The government therefore needed to provide a "supply of piped water, and an entirely new system of sewers, using circular, glazed clay pipes of relatively small bore instead of the old, square, brick tunnels".

However, there were some influential and powerful people who were opposed to Edwin Chadwick's ideas. These included the owners of private companies who in the past had made very large profits from supplying fresh water to middle-class districts in Britain's towns and cities. Opposition also came from prosperous householders who were already paying for these services and were worried that Chadwick's proposals would mean them paying higher taxes. The historian, A. L. Morton, claims that his proposed reforms made him "the most detested man in England."

Over 7,000 copies of the report was published and it helped create awareness of the need for government to take action in order to protect the lives of people living in Britain's towns and cities. Sir Robert Peel and his Conservative administration were unwilling to support Chadwick's recommendations. A pressure group, the Health of Towns Association, was formed in an effort to persuade Peel's government to take action.

When the government refused to take action, Chadwick set up his own company to provide sewage disposal and fresh water to the people of Britain. He planned to introduce the "arterial-venous system". The system involved one pipe taking the sewage from the towns to the countryside where it would be sold to farmers as manure. At the same time, another pipe would take fresh water from the countryside to the large populations living in the towns.

Chadwick calculated that it would be possible for people to have their sewage taken away and receive clean piped water for less than 2d. a week. However, Chadwick launched the Towns Improvement Company during the railway boom. Most people preferred to invest their money in railway companies. Without the necessary start-up capital, Chadwick was forced to abandon his plan.

Some local authorities did find Chadwick's ideas interesting and Nottingham became one of the first towns in Britain to pipe fresh water into all homes. Thomas Hawksley was appointed as chief enginner and in 1844 he was interviewed by a Parliamentary Committee about his work: "Before the supply was laid on in the houses water was sold chiefly to the labouring-classes by carriers at the rate of one farthing a bucket; and if the water had to be carried any distance up a court a halfpenny a bucket was, in some instances, charged. In general it was sold at about three gallons for a farthing. But the Company now delivers to all the town 76,000 gallons for £1; in other words, carries into every house 79 gallons for a farthing, and delivers water night and day, at every instant of time that it is wanted, at a charge 26 times less than the old delivery by hand."

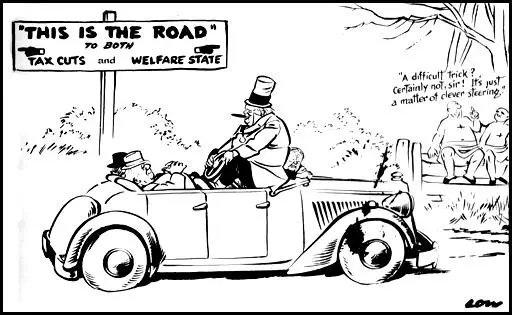

After the 1847 General Election, Lord John Russell became leader of a new Liberal government. The government proposed a Public Health Bill that was based on some of Edwin Chadwick's recommendations. There were still a large number of MPs who were strong supporters of what was known as laissez-faire. This was a belief that government should not interfere in the free market. They argued that it was up to individuals to decide on what goods or services they wanted to buy. These included spending on such things as sewage removal and water supplies. George Hudson, the Conservative Party MP, stated in the House of Commons: "The people want to be left to manage their own affairs; they do not want Parliament... interfering in everybody's business."

Supporters of Chadwick argued that many people were not well-informed enough to make good decisions on these matters. Other MPs pointed out that many people could not afford the cost of these services and therefore needed the help of the government. The Health of Towns Association, an organisation formed by doctors, began a propaganda campaign in favour of reform and encouraged people to sign a petition in favour of the Public Health Bill. In June 1847, the association sent Parliament a petition that contained over 32,000 signatures. However, this was not enough to persuade Parliament, and in July the bill was defeated.

A few weeks later news reached Britain of an outbreak of cholera in Egypt. The disease gradually spread west, and by early 1848 it had arrived in Europe. The previous outbreak of cholera in Britain in 1831, had resulted in the deaths of over 16,000 people. In his report, published in 1842, Chadwick had pointed out that nearly all these deaths had occurred in those areas with impure water supplies and inefficient sewage removal systems. Faced with the possibility of a cholera epidemic, the government decided to try again. This new bill involved the setting up of a Board of Health Act, that had the power to advise and assist towns which wanted to improve public sanitation.

In an attempt to persuade the supporters of laissez-faire to agree to a Public Health Act, the government made several changes to the bill introduced in 1847. For example, local boards of health could only be established when more than one-tenth of the ratepayers agreed to it or if the death-rate was higher than 23 per 1000. Chadwick was disappointed by the changes that had taken place, but he agreed to become one of the three members of the central Board of Health when the act was passed in the summer of 1848.

The new central Board of Health was to have three members, Edwin Chadwick, George Howard, Lord Morpeth and Anthony Ashley Cooper. Some people thought it was a good choice as "there would be no lack of enthusiasm, knowledge and energy at the core." However, The Lancet, the leading medical journal in the country described them "a benighted triumvirate" who should be ostracised and "left to the vacillations of their acknowledged ignorance".

Thomas Southwood Smith was later appointed to remedy the initial lack of a medical member. The Public Health Act was passed too late to stop the outbreak of cholera that arrived in Britain that September. The board took emergency action to ensure the regular cleansing of streets and waste removal. In the next few months, cholera killed 80,000 people. Once again, it was mainly the people living in the industrial slums who caught the disease. As Henry Mayhew pointed out: "The history of the late epidemic, which now seems to have almost spent its fatal fury upon us, has taught us that the masses of filth and corruption round the metropolis are, as it were, the nauseous nests of plague and pestilence."

As Peter Mandler has pointed out Edwin Chadwick tended to upset the government with his proposals: "Chadwick pressed upon them, and upon the new unitary commission for London, the replacement of the traditional brick sewers by his favoured comprehensive system of self-flushing, narrow diameter, glazed earthenware pipes, preferably conveying the sewage to farmers for use as manure. This dogma antagonized many engineers, as his earlier administrative dogmas had antagonized doctors. In autumn 1849, after a brief collapse brought on by overwork and possibly over-combativeness, Morpeth had to remove him from the metropolitan sewers commission."

Chadwick, who was appointed Sanitation Commissioner, had several ideas on how public health could be improved. This included a constant supply of fresh clean water, water closets in every house, and a system of carrying sewage to outlying farms, where it would provide a cheap source of fertilizer. Attempts to introduce public health reforms were resisted successfully by people with vested interests, for example, landlords and water companies, in maintaining the present system.

Michael Flinn has argued that there were a variety of different reasons why Chadwick had difficulty getting the full support from the government: "Personal dislike of a man in whose make-up arrogance and self-righteousness had a slighty disproportionate share can only partly explain it; the machinations of interested parties - representatives of the old, closed vestries, shareholders of private water companies, or slum landlords - may explain another part of it: probably resentment at the intrusion of meddling reformers in the business of the traditional governing classes led to some of the most destructive opposition."

By 1853 over 160 towns and cities had set up local boards of health. Some of these boards did extremely good work and were able to introduce important reforms. Thomas Hawksley, for example, after his success in Nottingham, was appointed to many major water supply projects across England, including schemes for Liverpool, Sheffield, Leicester, Leeds, Derby, Oxford, Cambridge, Sunderland, Lincoln, Darlington, Wakefield and Northampton.

In 1854 the Earl of Aberdeen appointed Lord Palmerston as his new Home Secretary. Palmerston was a supporter of public health reform. However, he came to the conclusion that Chadwick was so unpopular it would be impossible to persuade the House of Commons to renew the powers of the Board of Health while he remained in charge of the organisation. In order to preserve the reforms that he had achieved, Chadwick agreed to resign and was granted a £1000 per annum pension.

Edwin Chadwick died on 6th July, 1890. He was buried three days later in Mortlake Cemetery. In his will he left £47,000 to a trust "for the advancement of sanitary science and the physical training of the population".

On this day in 1864 Beatrice Harraden was born in London. She was educated at Cheltenham Ladies College, Queen's College, and Bedford College. She also spent time in Dresden.

Harraden's first novel, Ships That Pass in the Night, was published in 1893. This was followed by In Varying Moods (1894), The Remittance Man (1897), The Fowler (1899) and The Scholar's Daughter (1906).

In 1905 Harraden joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Millicent Fawcett, like other members of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), feared that the militant actions of the WSPU would alienate potential supporters of women's suffrage. However, Fawcett and other leaders of the NUWSS admired the courage of the suffragettes and at first were unwilling to criticize members of the WSPU.

In October 1906 Anne Cobden Sanderson, a former leading figure in the NUWSS, was arrested, along with members of the WSPU, Mary Gawthorpe, Charlotte Despard and Emmeline Pankhurst, in a large demonstration outside the House of Commons. After Sanderson's release the NUWSS organized a banquet at the Savoy on 11th December. Harraden sat between Minnie Baldock and Annie Kenney at the banquet.

In 1908 Harraden joined the Women's Writers Suffrage League (WWSL). The WWSL stated that its object was "to obtain the vote for women on the same terms as it is or may be granted to men. Its methods are those proper to writers - the use of the pen." Women writers who joined the organisation included Cicely Hamilton, Elizabeth Robins, Charlotte Despard, Alice Meynell, Margaret Nevinson, Evelyn Sharp and Marie Belloc Lowndes. Sympathetic male writers such as Israel Zangwill and Laurence Housman, were allowed to become "Honorary Men Associates".

In March 1908 Harraden read a chapter from Ships That Pass in the Night at a WSPU fund raising event. She also shared the platform with Christabel Pankhurst at a meeting of the WSPU in Hampstead in March 1910. She also wrote several articles for Votes for Women. She joined the Tax Resistance League and refused to pay tax on her royalties until women got the vote.

Beatrice Harraden left the WSPU during its arson campaign. She was also concerned about the health of hunger-strikers such as Emmeline Pankhurst and Lilian Lenton. She complained to Christabel Pankhurst, now living in exile in France, for risking the health of her members.

Other books by Harraden include Out of the Wreck I Rise (1914), The Guiding Thread (1916), Patuffa (1923), Rachel (1926) and Search Will Find It Out (1928).

Beatrice Harraden died on 5th May 1936.

On this day in 1888 Neysa McMein, the daughter of Harry McMein and Belle Parker, was born in Quincy, Illinois, on 24th January, 1888. Her father, a former reporter, worked for the family business, the McMein Publishing Company. It was a difficult marriage and the relationship was not helped by McMein's growing alcoholism.

McMein studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and in 1913 moved to New York City. Shortly after arriving she changed her name to Neysa. She briefly attempted to be an actress but in 1914 she began studying at the Art Students League. Later that year she sold her first illustration to Boston Star. In 1915 she did a portrait of Harry Horowitz (Gyp the Blood), the gunman about to be executed for the murder of Herman Rosenthal.

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has pointed out that she was an ardent supporter of women's suffrage. "One of the things Neysa came to New York to be was a fully emancipated woman: socially, sexually, and economically. With her, the matter was more personal than ideological. If she was a feminist... Neysa was one only by example. It was not that she did not participate in some aspects of the women's movement - Neysa was an ardent suffragist... but that she seemed to participate in such things instinctively rather than intellectually."

In 1915 Neysa McMein began producing front covers for the Saturday Evening Post. Her pastel drawings of young women proved highly popular and brought her many commissions. During the First World War she travelled to France and produced posters for the United States and French governments. In the summer of 1918 she spent time on the Western Front. She later recalled: "Since I have lived through air bombing I never will be frightened by anything on earth. The terror of air raids cannot be imagined. They are heralded by the blowing of sirens and the ringing of church bells, and amid this din the lights are extinguished and then suddenly come the bombs, falling no one knows where. The noise they made is worse than that of the battles." While she was in Paris she became friends with Private Harold Ross and Sergeant Alexander Woollcott. Both men were working for the army newspaper, Stars and Stripes.

After the war McMein began taking lunch with a group of writers in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel in New York City. Murdock Pemberton later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre. That, I might add, was no means cement for the gathering at any time... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table. Other regulars at these lunches included Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire.

Marc Connelly claims that the group spent a lot of time at the studio of Neysa McMein. "The world in which we moved was small, but it was churning with a dynamic group of young people who included Robert C. Benchley, Robert S. Sherwood, Ring Lardner, Dorothy Parker, Franklin. P. Adams, Heywood, Broun, Edna Ferber, Alice Duer Miller, Harold Ross, Jane Grant, Frank Sullivan, and Alexander Woollcott. We were together constantly. One of the habitual meeting places was the large studio of New York's preeminent magazine illustrator, Marjorie Moran McMein, of Muncie, Indiana. On the advice of a nurnerologist, she concocted a new first name when she became a student at the Chicago Art Institute. Neysa McMein. Neysa's studio on the northeast corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street was crowded all day by friends who played games and chatted with their startlingly beautiful young hostess as one pretty girl model after another posed for the pastel head drawings that would soon delight the eyes of America on the covers of such periodicals as the Ladies' Home Journal, Cosmopolitan, The American and The Saturday Evening Post."

Herbert Bayard Swope, H. L. Mencken, Arthur Krock and Janet Flanner were regular visitors to McMein's studio. H. G. Wells was fascinated with McMein and went to see her everyday when he visited New York City. The writer, George Bernard Shaw was another admirer. The nineteen year-old, Anaïs Nin, went to her studio to pose for her: "I met many celebrities there... it was so enjoyable, so bright and lively". She even told McMein, "It was so wonderful, posing for you, I hate to take the money for it." Another visitor commented: "Neysa had the nearest thing to a salon this country has ever seen... She might be in her smock and serve bad port but everyone came and everyone loved it."

Alexander Woollcott was another regular visitor: "Over at the piano Jascha Heifetz and Arthur Samuels may be trying to find out what four hands can do in the syncopation of a composition never thus desecrated before. Irving Berlin is encouraging them. Squatted uncomfortably around an ottoman, Franklin P. Adams, Marc Connelly and Dorothy Parker will be playing cold hands to see who will buy the dinner that evening. At the bookshelf Robert C. Benchley and Edna Ferber are amusing themselves vastly by thoughtfully autographing her set of Mark Twain for her. In the corner, some jet-bedecked dowager from a statelier milieu is taking it all in, immensely diverted. Chaplin, Alice Duer Miller or Wild Bill Donovan, Father Duffy or Mary Pickford - any or all of them may be there... If you loiter in Neysa McMein's studio, the world will drift in and out. Standing at the easel itself, oblivious of all the ructions, incredibly serene and intent on her work, is the artist herself."

In 1920 her good friend, Dorothy Parker, left her husband and moved in with McMein for a brief period. According to As John Keats, the author of You Might as Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker (1971): "She (Dorothy Parker) had taken an apartment in a building on West Fifty-seventh Street where the beautiful and somewhat Bohemian artist Neysa McMein had a studio. Miss Mcmein was a familiar of the Round Table, and her studio was a nocturnal headquarters for the Algonquin group. But Dorothy had taken the apartment because it was convenient to this meeting place of all her friends, and not for the purpose of sleeping with any of them."

In 1921 McMein, Ruth Hale and Jane Grant established the Lucy Stone League. The first list of members included Heywood Broun, Beatrice Kaufman, Franklin Pierce Adams, Belle LaFollette, Freda Kirchwey, Anita Loos, Zona Gale, Janet Flanner and Fannie Hurst. Its principles were forcefully expressed in a booklet written by Hale: "We are repeatedly asked why we resent taking one man's name instead of another's why, in other words, we object to taking a husband's name, when all we have anyhow is a father's name. Perhaps the shortest answer to that is that in the time since it was our father's name it has become our own that between birth and marriage a human being has grown up, with all the emotions, thoughts, activities, etc., of any new person. Sometimes it is helpful to reserve an image we have too long looked on, as a painter might turn his canvas to a mirror to catch, by a new alignment, faults he might have overlooked from growing used to them. What would any man answer if told that he should change his name when he married, because his original name was, after all, only his father's? Even aside from the fact that I am more truly described by the name of my father, whose flesh and blood I am, than I would be by that of my husband, who is merely a co-worker with me however loving in a certain social enterprise, am I myself not to be counted for anything."

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has argued: "Neysa McMein, as much as any American of the time, typified this contradictory decade. She was charming and eager and sophisticated, but she could be disarmingly provincial. She was liberated and self-supporting and casual - a few would say notoriously caasual - in sexual matters, but she was generally apolitical and still clung, at least nominally, to the rather conservative political tenents of her Republican upbringing in western Illinois."

Marc Connelly claimed: "Neysa couldn't have been more popular. She couldn't have been lovelier. Everybody loved her. She was perfectly beautiful, a tall Amazonian sort of person, handsome as could be." According to George Abbott "every taxi-cab driver, every salesgirl, every reader of columns, knew about the fabulous Neysa." Harpo Marx described her as "the sexiest gal in town" and admitted that "the biggest love affair in New York City was between me - along with two dozen other guys - and Neysa McMein." The screenwriter, Charles Brackett, was another admirer: "Why the bare word hello from her lips, and the way she brushed back her tawny hair with her wrist, should be so luminous with charm was incomprehensible."

Another close friend was Anita Loos: "Neysa was a magnificent young creature, a Brünnhilde with a classic face, tawny hair that scorned a brush or comb, and a style of dress for which her inspiration could only have been a grabbag. But all New York knew she was the heroine of a succession of romances with extremely prominent men. When Neysa invited me to her studio I accepted, but I confess to being critical of her; to me Neysa's unkempt appearance seemed phony and even a little conceited; it was if Cinderella had purposely gone to the ball in rags, knowing they'd make her all the more a sensation."

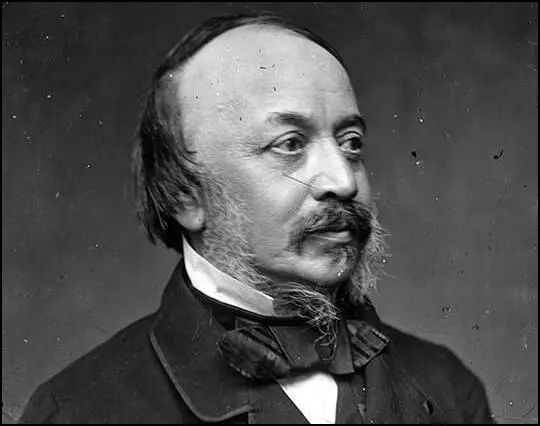

On this day in 1895 Randolph Churchill died at the age of forty-five. Churchill, the third son of John Spencer Churchill, seventh Duke of Marlborough (1822–1883), and his wife, Lady Frances Anne Churchill (1822–1899), the daughter of Charles William Vane, was born on 12th February 1849.

John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough, had led the English armies to victory on the continent against the French during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). In the course of the campaign he had looted large amounts of money and at the end of it had been rewarded, by a grateful Parliament with Blenheim Palace and a substantial endowment. However, by the time Randolph was born the family fortunes were greatly reduced."

Churchill was sent to preparatory school at Cheam, where he displayed an interest in history. At Eton College (1863–5) his record was unremarkable, but he became friends with Arthur Balfour and Earl of Rosebery, who were to have an important influence on his political career. He initially failed to get to Oxford University and had to resort to private lessons with an experienced tutor. In 1867 he entered university and read jurisprudence and modern history at Merton College. A member of the Bullingdon Club he developed a reputation for becoming involved in drunken brawls.

In 1873 Churchill met, at a ball at Cowes, a young American, Jennie Jerome, the daughter of Leonard Jerome, a wealthy New York financier. "Randolph and Jennie fell in love and became secretly engaged, but it took them six months to persuade their parents to allow them to marry. At this time, it was virtually unprecedented for the son of a leading aristocrat to marry an American, but Churchill was only the younger son of a poor duke, and when Leonard Jerome agreed to settle £50,000 on the couple, the duke agreed to the marriage."

Randolph Churchill and Jennie Jerome were married at the British embassy in Paris on 15th April 1874. Randolph Churchill shared the politics of his parents and in 1874, in return for his father's consent to marry, Churchill agreed to stand at the general election as the Conservative Party candidate for the borough of Woodstock, where his father was the principal landowner. It had less than 1,000 electors and he won the seat by obtaining only 569 votes.

Randolph Churchill's maiden speech in the House of Commons on 22nd May, 1874, was widely praised by leading Conservative Party politicians. Benjamin Disraeli was so impressed that he immediately wrote a letter to Queen Victoria about Churchill's speech: "the House was surprised, and then captivated, by his energy and natural flow and his impressive manner."

Sir Henry Irving, the famous actor, was also taken by this young politician: "Lord Randolph made a profound impression on me. As soon as I realised that he was not posing I said to myself: This is a great man, too; unconsciously he thinks that even Shakespeare needs his approval! He makes himself instinctively the measure of all things and of all men and doesn't trouble himself about the opinions or estimates of others."

Winston Churchill was born in Blenheim Palace, on 30th November, 1874, just seven and a half months after his parents were married. Clive Ponting, the author of Winston Churchill (1994) has pointed out: "Winston Churchill was born into the small, immensely influential and wealthy circle that still dominated English politics and society. For the whole of his life he remained an aristocrat at heart, deeply devoted to the interests of his family and drawing the majority of his friends and social acquaintances from the elite. From 1876 to 1880 he was brought up surrounded by servants amongst the splendors of the British ascendancy in Ireland."

Frank Harris was told by Louis John Jennings that in January 1875, Randolph Churchill was diagnosed as suffering from syphilis. He went to see his doctor and explained: "I want you to examine me at once. I got drunk last night and woke up in bed with an appalling old prostitute. Please examine me and apply some disinfectant." The doctor could not find anything wrong with him and it was not until several days later that the first symptoms appeared. "Inwardly I raged that I should have been such a fool. I, who prided myself on my brains, I was going to do such great things in the world, to have caught syphilis!"

Shane Leslie, the son of Jennie's sister Leonie, who said that Randolph's syphilis was contracted from a Blenheim housemaid shortly after Winston's birth. Once the disease was diagnosed, he could no longer sleep with his wife because syphilis was highly contagious and could be passed on to an unborn child. "The treatment of syphilis in those days was primitive, consisting of mercury and potassium iodine, and often ineffective. The disease went through three distinct stages, with periods of remission that made the victim think he was cured. In the second stage, sores appeared on the mouth, the groin became swollen, and there were pimples on the genitals. In the third and fatal stage, the mind became affected."

Randolph Churchill became a friend of the George, Prince of Wales, who was already friendly with his elder brother, George Spencer-Churchill, Marquess of Blandford. In 1875 Churchill criticized the Tory government's financial provision for the prince's visit to India in a letter which Benjamin Disraeli dismissed as an ill-informed Marlborough House manifesto. It is claimed by Roland Quinault this action destroyed Churchill's "rather rising reputation".

While Prince George was in India his companion, Heneage Finch, 7th Earl of Aylesford, decided to divorce his wife and cite the Marquess of Blandford as co-respondent. To prevent a scandal, Randolph Churchill threatened to make public intimate letters which Prince George had written to Lady Aylesford some years before. Aylesford abandoned his divorce proceedings, but the establishment was appalled by what was considered to be an attempt to blackmail the Royal Family. "The Duke of Marlborough was virtually forced to accept the Lord Lieutenancy of Ireland (at a personal cost of £30,000 a year) and take Lord Randolph as his secretary in order to remove him from London society."

On Disraeli's elevation to the House of Lords as Earl of Beaconsfield in 1876, Stafford Northcote became Leader of the Conservative party in the House of Commons. Northcote, who has serious health problems, was an ineffective leader. A group of Tory politicians, including Randolph Churchill, Arthur Balfour, Henry Drummond Wolff and John Eldon Gorst, were especial critical and became known as the "Fourth Party". This group "made a point of treating their leader with public mockery - Lord Randolph had a particularly irritating high pitched laugh which he used with much effect when Northcote spoke - and with private contempt which soon buzzed round the clubs."

In the 1880 General Election Churchill opposed the repeal of the Union, but also favoured reform of the Irish land tenure laws in the interests of internal peace. Churchill denounced the compensation for disturbance clause in the Relief of Distress Bill proposed by Hugh Law, the Attorney General for Ireland: "It was the tone of vindictive animosity towards landlords which pervaded the speech from the beginning to the end. He should really have been astonished had it been made by the hon. Member for the City of Cork (Mr. Parnell); but, coming as it did from one of the most able and respectable members of the Irish Bar, he was filled with considerable dismay. It occurred to him that if that speech faithfully represented the views of the Government, the Bill was not merely a temporary measure for the relief of Irish distress, but it was something widely different - it was the commencement of a campaign against landlords; it was the first step in a social war; it was an attempt to raise the masses against the propertied classes."

Charles Bradlaugh was a member of the Liberal Party and in the 1880 General Election he won the seat of Northampton. He was also the founder of the National Secular Society, an organisation opposed to Christian dogma. At this time the law required in the courts and oath from all witnesses. Bradlaugh saw this an opportunity to draw attention to the fact that "atheists were held to be incapable of taking a meaningful oath, and were therefore treated as outlaws."

Bradlaugh argued that the 1869 Evidence Amendment Act gave him a right he asked for permission to affirm rather than take the oath of allegiance. The Speaker of the House of Commons refused this request and Bradlaugh was expelled from Parliament. William Gladstone supported Bradlaugh's right to affirm, but as he had upset a lot of people with his views on Christianity, the monarchy and birth control and when the issue was put before Parliament, MPs voted to support the Speaker's decision to expel him.

Bradlaugh now mounted a national campaign in favour of atheists being allowed to sit in the House of Commons. Bradlaugh gained some support from some Nonconformists but he was strongly opposed by the Conservative Party and the leaders of the Anglican and Catholic clergy. When Bradlaugh attempted to take his seat in Parliament in June 1880, he was arrested by the Sergeant-at-Arms and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Bradlaugh received support from Benjamin Disraeli, who warned that Bradlaugh would become a martyr and it was decided to release him.

Randolph Churchill saw this as an opportunity to attack the leaderships of both parties on the subject of Bradlaugh: "In this matter Churchill was motivated not just by partisan opportunism but also by religious belief and parental example. His opposition to Gladstone's 1883 Affirmation Bill recalled his father's opposition to the alteration of the parliamentary oath in 1857. Churchill's denunciation of Bradlaugh's republicanism helped him to restore his credit with the prince of Wales, and he tried to exploit the hostility of the Catholic Irish MPs to Bradlaugh's advocacy of birth control."

26th April, 1881, Charles Bradlaugh was once again refused permission to affirm. William Gladstone promised to bring in legislation to enable Bradlaugh to do this, but this would take time. Bradlaugh was unwilling to wait and when he attempted to take his seat on 2nd August he was once forcibly removed from the House of Commons. Bradlaugh and his supporters organised a national petition and on 7th February, 1882, he presented a list of 241,970 signatures calling for him to be allowed to take his seat. However, when he tried to take the Parliamentary oath, he was once again removed from Parliament.

Stafford Northcote the leader of the Conservative Party in the House of Commons, became very angry about the behaviour of Churchill and attempted to make him toe the official party line. Churchill replied that: "Members who sit below the gangway have always acted in the House of Commons with a very considerable degree of independence of the recognized and constituted chiefs of either party; nor can I (who owe nothing to anyone and depend upon no one) in any way or at any time depart from that well-established and highly respectable tradition."

Randolph Churchill argued that Northcote should be replaced by Marquis of Salisbury. He questioned Northcote's leadership qualities and claimed that Salisbury was the only man capable of defeating and replacing William Gladstone. In an anonymous article in The Fortnightly Review, he argued that the leader of the Tory Party should be a member of the House of Lords, where he could influence government policy even when the party was in opposition. However, these constant attacks on Northcote backfired as Tory MPs rallied around to support him.

The opposition of Churchill and the "Fourth Party" to Charles Bradlaugh did not prevent his eventual admission to parliament, but it did lead to the creation on 17th November 1883 of the Primrose League. Its main objectives were: (i) To Uphold and support God, Queen, and Country, and the Conservative cause; (ii) To provide an effective voice to represent the interests of our members and to bring the experience of the Leaders to bear on the conduct of public affairs for the common good; (iii) To encourage and help our members to improve their professional competence as leaders; (iv) To fight for free enterprise. "Churchill was the first member of the league and his mother and wife became prominent members of the ladies' branch. The league quickly became a major force in popular Conservatism and the largest voluntary political organization in late Victorian Britain."

Randolph Churchill, sent his son, Winston, to an expensive preparatory school, St George's at Ascot, just before his eighth birthday. This was followed by a period in a boarding school in Brighton. He was considered to be a bright pupil with a phenomenal memory but he took little interest in subjects that did not stimulate him. It was claimed that he was "negligent, slovenly and perpetually late." He was very lonely and wrote to his mother: "I am wondering when you are coming to see me? I hope you are coming to see me soon... You must send someone to see me."

Randolph Churchill considered that his son was not bright enough to go to Eton. Instead he was sent to Harrow School. He was good in English and History but struggled in Latin and Mathematics. His behaviour remained bad. At the end of his first term his housemaster reported to his mother: "I do not think... that he is in any way wilfully troublesome: but his forgetfulness, carelessness, unpunctuality, and irregularity in every way, have really been so serious... As far as ability goes he ought to be at the top of his form, whereas he is at the bottom. Yet I do not think he is idle; only his energy is fitful, and when he gets to his work it is generally too late for him to do it well."

It has been claimed that Randolph Churchill had a difficult relationship with his son: "As Winston Churchill used to tell his own children, he never had more than five conversations with his father - or not conversations of any length; and he always had the feeling that he didn't quite measure up to expectations. He spent his youth in the certainty, relentlessly rubbed in by Randolph, that he must be less clever than his father. Randolph had been to Eton, whereas it was thought safer to send young Winston to Harrow - partly because of his health (the air of the hill being deemed better for his fragile lungs than the dank air by the Thames) but really because Harrow, in those days, was supposed to be less intellectually demanding."

In 1883 Randolph Churchill called for a £10 million reduction in spending to be achieved by cuts in the army and the civil service. During this period he became leader of the "Tory Democracy" movement. He defined this as merely popular support for the monarchy, the House of Lords, and the Church of England - the traditional bulwarks of toryism. Churchill showed little interest in social questions and he did not advocate expensive welfare measures. Churchill took no interest in working-class housing, although it was a fashionable issue at the time. His popularity with the masses owed little to his direct interest in their welfare, but much to the aggressiveness of his platform speeches. His main target was Gladstone who he described as "the greatest living master of the art of personal advertisement".

In May 1885 Churchill helped to orchestrate the defeat of Gladstone's Liberal government on a budget amendment opposing the increase in taxation and the absence of rate relief. Marquis of Salisbury became prime minister; Michael Hicks Beach was chancellor of the exchequer and leader of the House of Commons, while Stafford Northcote - held the largely nominal post of first lord of the Treasury. Churchill became secretary of state for India. The Conservative government was defeated on 26th January 1886. Although he won his seat in the subsequent General Election the Liberal Party returned to power. This caused Churchill financial problems who apparently remarked, "We're out of office, and they're economising on me."

William Gladstone and the Liberals won the election with a majority of seventy-two over the Tories. However, the Irish Nationalists could cause problems because they won 86 seats. On 8th April 1886, Gladstone announced his plan for Irish Home Rule. Mary Gladstone Drew wrote: "The air tingled with excitement and emotion, and when he began his speech we wondered to see that it was really the same familiar face - familiar voice. For 3 hours and a half he spoke - the most quiet earnest pleading, explaining, analysing, showing a mastery of detail and a grip and grasp such as has never been surpassed. Not a sound was heard, not a cough even, only cheers breaking out here and there - a tremendous feat at his age... I think really the scheme goes further than people thought."

The Home Rule Bill said that there should be a separate parliament for Ireland in Dublin and that there would be no Irish MPs in the House of Commons. The Irish Parliament would manage affairs inside Ireland, such as education, transport and agriculture. However, it would not be allowed to have a separate army or navy, nor would it be able to make separate treaties or trade agreements with foreign countries.

Randolph Churchill advised Marquis of Salisbury to defend the Union by forming an alliance with the Spencer Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington and the other Liberals who opposed home rule. Churchill was the first prominent politician to advocate the creation of a "unionist party" - a coalition of Conservatives and unionist Liberals - which would maintain Britain's ties not only with Ireland but also with India and the empire. Churchill also decided to "play the Orange card" - to exploit the strong opposition of Ulster protestants to home rule.In a letter published in The Times, Churchill advocated enlightened unionism, but stated that if the Liberal government ignored the opposition to home rule, then "Ulster will fight, Ulster will be right".

The Conservative Party opposed the measure. So did some members of the Liberal Party, led by Joseph Chamberlain, also disagreed with Gladstone's plan. Chamberlain main objection to Gladstone's Home Rule Bill was that as there would be no Irish MPs at Westminster, Britain and Ireland would drift apart. He added that this would be amounting to the start of the break-up of the British Empire. When a vote was taken, there were 313 MPs in favour, but 343 against. Of those voting against, 93 were Liberals. They became known as Liberal Unionists.

William Gladstone responded to the vote by dissolving parliament rather than resign. During the 1886 General Election he had great difficultly leading a divided party. According to Colin Matthew: "So dedicated was Gladstone to the campaign that he agreed to break the habit of the previous forty years and cease his attempts to convert prostitutes, for fear, for the first time, of causing a scandal (Liberal agents had heard that the Unionists were monitoring Gladstone's nocturnal movements in London with a view to a press exposé)". Churchill made an impassioned attack on Gladstone and his home-rule policy. He claimed that both the British constitution and the Liberal Party were being broken up merely "to gratify the ambition of an old man in a hurry".

In the 1886 General Election the number of Liberal MPs fell from 333 in 1885 to 196, though no party gained an overall majority. William Gladstone resigned on 30th July. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, once again became prime minister. Queen Victoria wrote him a letter where she said she always thought that his Irish policy was bound to fail and "that a period of silence from him on this issue would now be most welcome, as well as his clear patriotic duty."

Salisbury formed a Conservative government and offered Churchill the leadership of the House of Commons. Churchill combined the leadership of the house with the post of chancellor of the exchequer and was thus second only to Salisbury in the ministerial hierarchy. It is claimed that Churchill acted as if he was the leader of the Conservative Party. In a speech at Dartford, he warned Conservatives not to rest on their laurels since "Politics is not a science of the past; politics is a science of the future". He also declared that "The main principle and guiding motive of the Government in the future will be to maintain intact and unimpaired the union of the Unionist party'".

Salisbury acknowledged Churchill's ability, but complained that he had a "wayward and headstrong disposition" and likened the cabinet to "an orchestra in which the first fiddle plays one tune and everybody else, including myself, wishes to play another" When the journalist, Alfred Austin, alleged that Churchill wished to supplant the premier, Salisbury observed that "the qualities for which he is most conspicuous have not usually kept men for any length of time at the head of affairs".

As chancellor of the exchequer Randolph Churchill was determined to be a reformer. His draft budget for 1887 proposed a radical overhaul of the tax system. "Churchill proposed to take 3d. off income tax, lower the duty on tea and tobacco, graduate the house and death duties, and double the government's rate support grant to local authorities. The scheme, though radical, was relatively kind to landowners and not socially redistributive."

Churchill's priority as chancellor was to reduce the defence estimates below those of the last Liberal government. This was opposed by the secretary for war, William Henry Smith. The dispute came to focus on the £500,000 allocated for the fortification of ports and coaling stations. When Smith refused to give way, Churchill wrote to Salisbury, on 20th December 1886, stating his wish to resign from the government since he could not accept the defence estimates and did not expect support from the cabinet. Churchill expected Salisbury to support him in this dispute. He was wrong and Salisbury, in his reply, supported Smith and accepted Churchill's resignation with "profound regret"

Churchill then justified his resignation by linking his desire for economy with wider issues: "I remember the vulnerable and scattered character of the empire, the universality of our commerce, the peaceful tendencies of our democratic electorate, and the hard times, the pressure of competition, and the high taxation now imposed … it is only the sacrifice of a chancellor of the exchequer upon the altar of thrift and economy which can rouse the people to take stock of their lives, their position and their future."

After leaving office, he admitted that he was physically exhausted and immediately went on a long vacation to the Mediterranean to recuperate. He experienced alternating phases of mania and euphoria. He was brought back from holiday in Canada in a straight-jacket. He died at the age of forty-five on 24th January 1895. His neurologist diagnosed his illness as syphilis, though it has recently been argued that his symptoms could have been caused by a tumour on the brain."

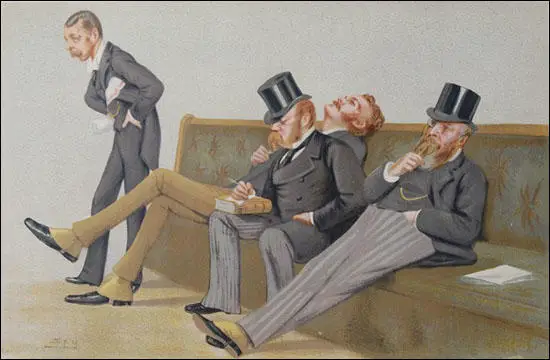

Henry Drummond Wolff and John Eldon Gorst (1st December 1880)

On this day in 1958 Charles Trevelyan died aged 87. Trevelyan, the son of George Otto Trevelyan, the Liberal MP, was born in Park Lane, London, on 28th October 1870. His mother, Caroline Philips, was the daughter of Robert Needham Philips, who was also a member of the House of Commons. Over the next few years he served under William Ewart Gladstone in several cabinet posts.

Charles' brother, George Macaulay Trevelyan, later claimed that their childhood was very political. He described how "a sense of drama of English and Irish history was purveyed to me through daily sights and experiences, with my father as commentator and bard."

His father was very wealthy and the family lived in three different houses. This included a large house in London, Welcombe House, a red-brick mansion in Straford-upon-Avon, and Wallington Hall in Morpeth. In 1880 he was sent to a preparatory school at Hoddesdon called The Grange.

Charles was educated at Harrow and Trinity College where he became friends with Bertrand Russell. (4) He graduated from Cambridge University in 1892 with a second-class history degree. He was upset he did not get a first: "Things are past the point of redemption. Oh it is so horrible. All my courage is gone, all my strong self confidence, all my hope. The very brightness of my prospects as the world would say, is a curse on me! What can it lead to but the repetition of the same miserable story of inadequacy and inefficiency in the end?"

Charles Trevelyan helped John Morley in his successful campaign to become MP for Newcastle. Morley arranged for him to become Lord Houghton's private secretary. Houghton was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and the job involved Trevelyan working in Dublin.

He was a supporter of Home Rule and disliked the way the administration spoke about the Irish people: "One of the men spoke of politics and Home Rule bitterly, in that high-handed, disdainful, superior way that only Tories can speak, spurning their hearer's opinions, getting the ruder and more blatant if they see he objects. He spoke of the Irish as ruffians, and used the worst sort of language towards them."

In 1895 Charles Trevelyan joined the Fabian Society and developed a close relationship with Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw, Bertrand Russell, H. G. Wells, Herbert Samuel and Graham Wallas. During this period he developed socialistic views on social reform. He was especially impressed by the views of one of his new friends: "Shaw gives the best exposition of the state of things one could hope to hear."

Members disagreed about Trevelyan's abilities. Beatrice Webb described him as "a man who had every endowment - social position, wealth, intelligence, an independent outlook, good looks, good manners". H. G. Wells was less impressed and argued that "undoubtedly high-minded, Trevelyan had little sense of humour or irony, and was only marginally less self-satisfied and unendurably boring than his youngest brother, George." Bertrand Russell thought he was less gifted than his two brothers.

Charles Trevelyan was adopted as the Liberal Party parliamentary candidate for North Lambeth, but was narrowly defeated in the 1895 General Election. The following year he argued that he was attracted to the philosophy of socialism. "I have the greatest sympathy with the growth of the socialist party. I think they understand the evils that surround us and hammer them into people's minds better than we Liberals. I want to see the Liberal party throw its heart and soul fearlessly into reform so as to prevent a reaction from the present state of thugs and the violent revolution that would inevitably follow it."

Trevelyan took a strong interest in education and in 1896 he was elected to the London School Board. Family influence enabled him to being adopted for the constituency of Elland, and entered parliament after a by-election in March 1899. Charles Trevelyan was a very independent member of the House of Commons and took his brother's advice: "It is a rule that no Trevelyan ever sucks up either to the press, or the chiefs, or the 'right people'. The world has given us money enough to enable us to do what we think is right. We thank it for that and ask no more of it, but to be allowed to serve it."

Charles Trevelyan met and fell in love with Mary Katharine Bell, the daughter of Sir Hugh Bell, a wealthy businessman. In a letter he sent on 20th December, 1903, he outlined his his career prospects. "I am constantly anxious that in your newness to affairs you should not make pretty dreams for yourself of great success for me... I have not the quickness, variety or imagination of outlook which can possibly enable me ever to deal with the complicated revolutions of our national politics. I can only do my duty. And so little do I think there is any good chance of rising to any high position with my mediocre store of knowledge and ability, that I shall try less and less to try for position and more and more to take a line I think right." They married on 6th January 1904. Over the next few years they had three sons and four daughters.

Following the 1906 General Election, Trevelyan was disappointed not to be offered a post in the Liberal Government headed by Henry Campbell-Bannerman. It was generally believed that the reason for this was Trevelyan's left-wing political views. His cousin, Morgan Philips Price, commented that "his sincerity often led him to be intolerant of other people's opinions, and with a greater degree of tact he could have accomplished much more of what he wanted."

In the House of Commons Trevelyan advocated taxation of land values, Liberal–Labour co-operation on social legislation, and the ending of the House of Lords. As his biographer pointed out: "Trevelyan's comments upon his party's elders and leaders were often tactless, while his attacks upon policies he considered mistaken were intemperate. Not a trimmer by nature, his demeanour frequently suggested impatience and insensitivity."

In October 1908, the new Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, appointed Trevelyan to the junior post of parliamentary under-secretary at the Board of Education. In this post he argued passionately for the establishment of a completely secular system of national education. This made him unpopular with MPs who held strong religious beliefs.

In the 1910 General Election Trevelyan suggested that it was important to reform Parliament: "I wish to make it clear from the onset that at the coming election I want support on no other understanding that the new Parliament is to destroy once and for ever, the power of the hereditary chamber to reverse the decisions of the representatives of the people. The power to delay or reject supplies must be abolished, and they must never again enjoy an absolute veto over ordinary legislation. They have rendered fruitless the most serious work of the present House of Commons."

At the end of July, 1914, it became clear to the British government that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Four senior members of the government, Charles Trevelyan, David Lloyd George, John Burns and John Morley, were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war. They informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, to change his mind.

The anti-war newspaper, The Daily News, commented: "Among the many reports which are current as to Ministerial resignations there seems to be little doubt in regard to three. They are those of Lord Morley, Mr. John Burns, and Mr. Charles Trevelyan. There will be widespread sympathy with the action they have taken. Whether men approve of that action or not it is a pleasant thing in this dark moment to have this witness to the sense of honour and to the loyalty to conscience which it indicates... Mr. Trevelyan will find abundant work in keeping vital those ideals which are at the root of liberty and which are never so much in danger as in times of war and social disruption."

In a letter to his constituents Trevelyan explained his reasons for resignation: "However overwhelming the victory of our navy, our commerce will suffer terribly. In war too, the first productive energies of the whole people have to be devoted to armaments. Cannon are a poor industrial exchange for cotton. We shall suffer a steady impoverishment as the character of our work exchanges. All this I felt so strongly that I cannot count the cause adequate which is to lead to this misery. So I have resigned."

However, Trevelyan's actions were extremely unpopular with most people. A. J. A. Morris has argued that it was clear to Trevelyan that "Britain was condemned to war for no better reason than sentimental attachment to France and hatred of Germany. Trevelyan resigned from the government in protest. By this action he found himself estranged from most of his family, condemned and vilified by a hysterical press, and rejected by his constituency association."

George Lansbury, a senior figure in the Labour Party praised the actions of Charles Trevelyan and predicted it marked the end of his political career: "He must have known when he resigned that he was giving the death blow to his career, and the courage which compels such a step is not to be distinguished from the courage of a soldier who falls in battle".

The journalist, Morgan Philips Price, went to see Charles Trevelyan and suggested that they formed an organisation against the First World War. Trevelyan now made contact with two pacifist members of the Liberal Party, Norman Angell and E. D. Morel, and Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party. They also had discussions with Bertrand Russell and Arthur Ponsonby, who had also spoken out against the war.

A meeting was held and after considering names such as the Peoples' Emancipation Committee and the Peoples' Freedom League, they selected the Union of Democratic Control. Other members included J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Ottoline Morrell, Philip Morrell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Arnold Rowntree, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Tom Johnston, Philip Snowden, Ethel Snowden, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Mary Sheepshanks, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Eileen Power, Israel Zangwill, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville, Hastings Lees-Smith and Olive Schreiner.

Members of the UDC agreed that one of the main reasons for the conflict was the secret diplomacy of people like Britain's foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey. They decided that the Union of Democratic Control should have three main objectives: (i) that in future to prevent secret diplomacy there should be parliamentary control over foreign policy; (ii) there should be negotiations after the war with other democratic European countries in an attempt to form an organisation to help prevent future conflicts; (iii) that at the end of the war the peace terms should neither humiliate the defeated nation nor artificially rearrange frontiers as this might provide a cause for future wars.

Over the next couple of years the UDC became the leading anti-war organisation in Britain. Trevelyan wrote articles for newspapers and gave a series of lectures on the need to negotiate a peace with Germany. As a result of this Trevelyan was condemned in the popular press as being a "pro-German, unpatriotic, scoundrel". He was also criticised for his stance on the war by his father, George Otto Trevelyan. However, Trevelyan continued to campaign for a peace settlement with Germany.

The Daily Sketch launched a personal attack on Charles Trevelyan accusing him of being pro-German: "Trevelyan would then have a very congenial atmosphere - in the Reichstag. We have no time to listen to his foolish and pernicious talk. It is a scandal that he should be in Parliament when he continues to preach these pro-German and utterly impracticable pacifist doctrines. Trevelyan must go".

Charles was especially upset by the criticism of his older brother, George Macaulay Trevelyan. "I know that wisdom may begin to come to poor human beings through misery. But even I doubt when I see people like George carried away by shallow fears and ill-informed hatreds... It shows how absurdly far we are from brotherly feeling to foreigners when even in him it is a shallow veneer. He like all the rest wants to hate the Germans... I am more discouraged by it than anything else because it shows the helplessness of intellect before national passion."

The Daily Express listed details of future UDC meetings and encouraged its readers to go and break-up them up. Although the UDC complained to the Home Secretary about what it called "an incitement to violence" by the newspaper, he refused to take any action. Over the next few months the police refuse to protect UDC speakers and they were often attacked by angry crowds. After one particularly violent event on 29th November, 1915, the newspaper proudly reported the "utter rout of the pro-Germans".

The government saw Union of Democratic Control as an extremely dangerous organisation. Basil Thompson, head of the Criminal Investigation Division of Scotland Yard, and future head of Special Branch, was asked to investigate the UDC. Thompson reported that the UDC "is not a revolutionary body, and it has been appealing, at any rate in the early days of the war, more to the intellectual classes than to the working class". He went on to argue that its funds came from the Society of Friends and "Messrs. Cadbury, Fry and Rowntree".

George Bernard Shaw urged Trevelyan to become the leader of the progressive forces in the House of Commons: "You have great advantages: you have an unassailable social and financial position, intellectual integrity and historical consciousness, character, personality, good looks, style, conviction, everything they lack except cinema sentiment and vulgarity. If you feel equal to a deliberate assumption of responsibility it is clear to me that you... can very soon become the visible alternative nucleus to the George gang and the Asquith ruin."

On 2nd February 1918 Trevelyan published in the radical weekly The Nation the assertion that the Labour Party, and not the Liberal Party, was now best fitted to root out the evils of social and economic privilege. "Our lives have been spoilt by compromise, because we tolerated armament firms and secret diplomacy and the rule of wealth. The world war has revealed the real meaning of our social system. As imperialism, militarism and irresponsible wealth are everywhere trying to crush democracy today, so democracy must treat these forces without mercy. The root of all evil is economic privilege... Where shall we find the political combination which will offer us resource in its strategy, coherence in its policy, and fearlessness in its proposals?"

Charles Trevelyan's parents were upset when he told them he was going to join the Labour Party. His mother wrote: "Your decision to join the Labour party is, of course, a trouble to us. I hope you will get on with your new friends and not let them lead you into deep waters. It will make a considerable difference to you and your family but you have doubtless considered everything. I had hoped that after the war we might find ourselves all more in sympathy on public affairs."

Charles replied that the Labour Party in the future would become the main force of progressive change: "I think from your letter you are looking from the wrong angle at my action in joining the Labour party. I of course knew that you would regret my leaving the Liberal party, but there is nothing unnatural, sudden or surprising about it. You talk of 'my new friends'. In the first place I have worked in close comradeship with several of the leaders of the Labour party for four years. There is nothing to choose in personality, ability, or character between them and the pick of the Liberal Cabinet, with whom I previously associated in politics. But beyond that at least half my Liberal friends are either joining the Labour party now or are on the verge of joining it... Any amount of my private friends of the same education, and, if that matters, social position, are joining now. I don't want to make you realise this in order to make you uncomfortable about the Liberal party, but in order that you may be comfortable about me."