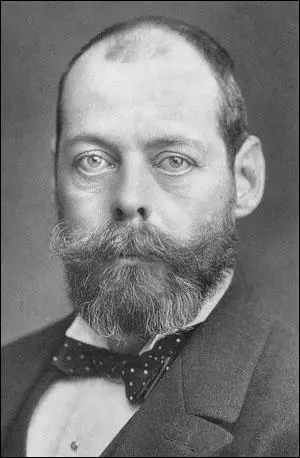

Randolph Churchill

Randolph Churchill, the third son of John Spencer Churchill, seventh Duke of Marlborough (1822–1883), and his wife, Lady Frances Anne Churchill (1822–1899), the daughter of Charles William Vane, was born on 12th February 1849. (1)

John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough, had led the English armies to victory on the continent against the French during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). In the course of the campaign he had looted large amounts of money and at the end of it had been rewarded, by a grateful Parliament with Blenheim Palace and a substantial endowment. However, by the time Randolph was born the family fortunes were greatly reduced." (2)

Churchill was sent to preparatory school at Cheam, where he displayed an interest in history. At Eton College (1863–5) his record was unremarkable, but he became friends with Arthur Balfour and Earl of Rosebery, who were to have an important influence on his political career. He initially failed to get to Oxford University and had to resort to private lessons with an experienced tutor. In 1867 he entered university and read jurisprudence and modern history at Merton College. A member of the Bullingdon Club he developed a reputation for becoming involved in drunken brawls. (3)

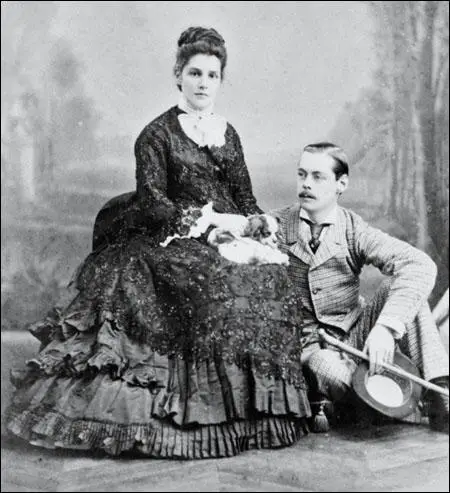

In 1873 Churchill met, at a ball at Cowes, a young American, Jennie Jerome, the daughter of Leonard Jerome, a wealthy New York financier. "Randolph and Jennie fell in love and became secretly engaged, but it took them six months to persuade their parents to allow them to marry. At this time, it was virtually unprecedented for the son of a leading aristocrat to marry an American, but Churchill was only the younger son of a poor duke, and when Leonard Jerome agreed to settle £50,000 on the couple, the duke agreed to the marriage." (4)

Randolph Churchill in the House of Commons

Randolph Churchill and Jennie Jerome were married at the British embassy in Paris on 15th April 1874. Randolph Churchill shared the politics of his parents and in 1874, in return for his father's consent to marry, Churchill agreed to stand at the general election as the Conservative Party candidate for the borough of Woodstock, where his father was the principal landowner. It had less than 1,000 electors and he won the seat by obtaining only 569 votes. (5)

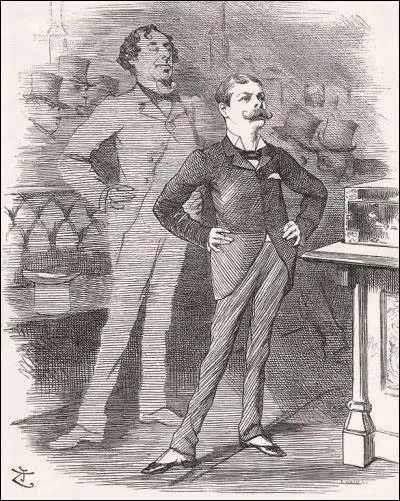

Randolph Churchill's maiden speech in the House of Commons on 22nd May, 1874, was widely praised by leading Conservative Party politicians. Benjamin Disraeli was so impressed that he immediately wrote a letter to Queen Victoria about Churchill's speech: "the House was surprised, and then captivated, by his energy and natural flow and his impressive manner." (6)

Sir Henry Irving, the famous actor, was also taken by this young politician: "Lord Randolph made a profound impression on me. As soon as I realised that he was not posing I said to myself: This is a great man, too; unconsciously he thinks that even Shakespeare needs his approval! He makes himself instinctively the measure of all things and of all men and doesn't trouble himself about the opinions or estimates of others." (7)

Winston Churchill was born in Blenheim Palace, on 30th November, 1874, just seven and a half months after his parents were married. Clive Ponting, the author of Winston Churchill (1994) has pointed out: "Winston Churchill was born into the small, immensely influential and wealthy circle that still dominated English politics and society. For the whole of his life he remained an aristocrat at heart, deeply devoted to the interests of his family and drawing the majority of his friends and social acquaintances from the elite. From 1876 to 1880 he was brought up surrounded by servants amongst the splendors of the British ascendancy in Ireland." (8)

Frank Harris was told by Louis John Jennings that in January 1875, Randolph Churchill was diagnosed as suffering from syphilis. He went to see his doctor and explained: "I want you to examine me at once. I got drunk last night and woke up in bed with an appalling old prostitute. Please examine me and apply some disinfectant." The doctor could not find anything wrong with him and it was not until several days later that the first symptoms appeared. "Inwardly I raged that I should have been such a fool. I, who prided myself on my brains, I was going to do such great things in the world, to have caught syphilis!" (9)

Shane Leslie, the son of Jennie's sister Leonie, who said that Randolph's syphilis was contracted from a Blenheim housemaid shortly after Winston's birth. Once the disease was diagnosed, he could no longer sleep with his wife because syphilis was highly contagious and could be passed on to an unborn child. "The treatment of syphilis in those days was primitive, consisting of mercury and potassium iodine, and often ineffective. The disease went through three distinct stages, with periods of remission that made the victim think he was cured. In the second stage, sores appeared on the mouth, the groin became swollen, and there were pimples on the genitals. In the third and fatal stage, the mind became affected." (10)

Blackmail of Prince of Wales

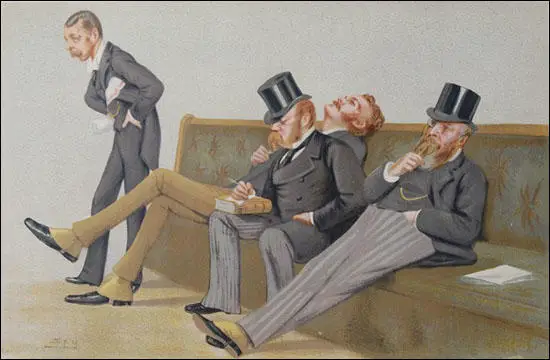

Randolph Churchill became a friend of the George, Prince of Wales, who was already friendly with his elder brother, George Spencer-Churchill, Marquess of Blandford. In 1875 Churchill criticized the Tory government's financial provision for the prince's visit to India in a letter which Benjamin Disraeli dismissed as an ill-informed Marlborough House manifesto. It is claimed by Roland Quinault this action destroyed Churchill's "rather rising reputation". (11)

While Prince George was in India his companion, Heneage Finch, 7th Earl of Aylesford, decided to divorce his wife and cite the Marquess of Blandford as co-respondent. To prevent a scandal, Randolph Churchill threatened to make public intimate letters which Prince George had written to Lady Aylesford some years before. Aylesford abandoned his divorce proceedings, but the establishment was appalled by what was considered to be an attempt to blackmail the Royal Family. "The Duke of Marlborough was virtually forced to accept the Lord Lieutenancy of Ireland (at a personal cost of £30,000 a year) and take Lord Randolph as his secretary in order to remove him from London society." (12)

Fourth Party

On Disraeli's elevation to the House of Lords as Earl of Beaconsfield in 1876, Stafford Northcote became Leader of the Conservative party in the House of Commons. Northcote, who has serious health problems, was an ineffective leader. A group of Tory politicians, including Randolph Churchill, Arthur Balfour, Henry Drummond Wolff and John Eldon Gorst, were especial critical and became known as the "Fourth Party". This group "made a point of treating their leader with public mockery - Lord Randolph had a particularly irritating high pitched laugh which he used with much effect when Northcote spoke - and with private contempt which soon buzzed round the clubs." (13)

Henry Drummond Wolff and John Eldon Gorst (1st December 1880)

In the 1880 General Election Churchill opposed the repeal of the Union, but also favoured reform of the Irish land tenure laws in the interests of internal peace. Churchill denounced the compensation for disturbance clause in the Relief of Distress Bill proposed by Hugh Law, the Attorney General for Ireland: "It was the tone of vindictive animosity towards landlords which pervaded the speech from the beginning to the end. He should really have been astonished had it been made by the hon. Member for the City of Cork (Mr. Parnell); but, coming as it did from one of the most able and respectable members of the Irish Bar, he was filled with considerable dismay. It occurred to him that if that speech faithfully represented the views of the Government, the Bill was not merely a temporary measure for the relief of Irish distress, but it was something widely different - it was the commencement of a campaign against landlords; it was the first step in a social war; it was an attempt to raise the masses against the propertied classes." (14)

Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh was a member of the Liberal Party and in the 1880 General Election he won the seat of Northampton. He was also the founder of the National Secular Society, an organisation opposed to Christian dogma. At this time the law required in the courts and oath from all witnesses. Bradlaugh saw this an opportunity to draw attention to the fact that "atheists were held to be incapable of taking a meaningful oath, and were therefore treated as outlaws." (15)

Bradlaugh argued that the 1869 Evidence Amendment Act gave him a right he asked for permission to affirm rather than take the oath of allegiance. The Speaker of the House of Commons refused this request and Bradlaugh was expelled from Parliament. William Gladstone supported Bradlaugh's right to affirm, but as he had upset a lot of people with his views on Christianity, the monarchy and birth control and when the issue was put before Parliament, MPs voted to support the Speaker's decision to expel him. (16)

Bradlaugh now mounted a national campaign in favour of atheists being allowed to sit in the House of Commons. Bradlaugh gained some support from some Nonconformists but he was strongly opposed by the Conservative Party and the leaders of the Anglican and Catholic clergy. When Bradlaugh attempted to take his seat in Parliament in June 1880, he was arrested by the Sergeant-at-Arms and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Bradlaugh received support from Benjamin Disraeli, who warned that Bradlaugh would become a martyr and it was decided to release him. (17)

Randolph Churchill saw this as an opportunity to attack the leaderships of both parties on the subject of Bradlaugh: "In this matter Churchill was motivated not just by partisan opportunism but also by religious belief and parental example. His opposition to Gladstone's 1883 Affirmation Bill recalled his father's opposition to the alteration of the parliamentary oath in 1857. Churchill's denunciation of Bradlaugh's republicanism helped him to restore his credit with the prince of Wales, and he tried to exploit the hostility of the Catholic Irish MPs to Bradlaugh's advocacy of birth control." (18)

26th April, 1881, Charles Bradlaugh was once again refused permission to affirm. William Gladstone promised to bring in legislation to enable Bradlaugh to do this, but this would take time. Bradlaugh was unwilling to wait and when he attempted to take his seat on 2nd August he was once forcibly removed from the House of Commons. Bradlaugh and his supporters organised a national petition and on 7th February, 1882, he presented a list of 241,970 signatures calling for him to be allowed to take his seat. However, when he tried to take the Parliamentary oath, he was once again removed from Parliament. (19)

Dispute with Stafford Northcote

Stafford Northcote the leader of the Conservative Party in the House of Commons, became very angry about the behaviour of Churchill and attempted to make him toe the official party line. Churchill replied that: "Members who sit below the gangway have always acted in the House of Commons with a very considerable degree of independence of the recognized and constituted chiefs of either party; nor can I (who owe nothing to anyone and depend upon no one) in any way or at any time depart from that well-established and highly respectable tradition." (20)

Churchill argued that Northcote should be replaced by Marquis of Salisbury. He questioned Northcote's leadership qualities and claimed that Salisbury was the only man capable of defeating and replacing William Gladstone. In an anonymous article in The Fortnightly Review, he argued that the leader of the Tory Party should be a member of the House of Lords, where he could influence government policy even when the party was in opposition. However, these constant attacks on Northcote backfired as Tory MPs rallied around to support him. (21)

The opposition of Churchill and the "Fourth Party" to Charles Bradlaugh did not prevent his eventual admission to parliament, but it did lead to the creation on 17th November 1883 of the Primrose League. Its main objectives were: (i) To Uphold and support God, Queen, and Country, and the Conservative cause; (ii) To provide an effective voice to represent the interests of our members and to bring the experience of the Leaders to bear on the conduct of public affairs for the common good; (iii) To encourage and help our members to improve their professional competence as leaders; (iv) To fight for free enterprise. "Churchill was the first member of the league and his mother and wife became prominent members of the ladies' branch. The league quickly became a major force in popular Conservatism and the largest voluntary political organization in late Victorian Britain." (22)

Winston Churchill

Randolph Churchill, sent his son, Winston, to an expensive preparatory school, St George's at Ascot, just before his eighth birthday. This was followed by a period in a boarding school in Brighton. He was considered to be a bright pupil with a phenomenal memory but he took little interest in subjects that did not stimulate him. It was claimed that he was "negligent, slovenly and perpetually late." He was very lonely and wrote to his mother: "I am wondering when you are coming to see me? I hope you are coming to see me soon... You must send someone to see me." (23)

Randolph Churchill considered that his son was not bright enough to go to Eton. Instead he was sent to Harrow School. He was good in English and History but struggled in Latin and Mathematics. His behaviour remained bad. At the end of his first term his housemaster reported to his mother: "I do not think... that he is in any way wilfully troublesome: but his forgetfulness, carelessness, unpunctuality, and irregularity in every way, have really been so serious... As far as ability goes he ought to be at the top of his form, whereas he is at the bottom. Yet I do not think he is idle; only his energy is fitful, and when he gets to his work it is generally too late for him to do it well." (24)

It has been claimed that Randolph Churchill had a difficult relationship with his son: "As Winston Churchill used to tell his own children, he never had more than five conversations with his father - or not conversations of any length; and he always had the feeling that he didn't quite measure up to expectations. He spent his youth in the certainty, relentlessly rubbed in by Randolph, that he must be less clever than his father. Randolph had been to Eton, whereas it was thought safer to send young Winston to Harrow - partly because of his health (the air of the hill being deemed better for his fragile lungs than the dank air by the Thames) but really because Harrow, in those days, was supposed to be less intellectually demanding." (25)

In 1883 Randolph Churchill called for a £10 million reduction in spending to be achieved by cuts in the army and the civil service. (26) During this period he became leader of the "Tory Democracy" movement. He defined this as merely popular support for the monarchy, the House of Lords, and the Church of England - the traditional bulwarks of toryism. Churchill showed little interest in social questions and he did not advocate expensive welfare measures. Churchill took no interest in working-class housing, although it was a fashionable issue at the time. His popularity with the masses owed little to his direct interest in their welfare, but much to the aggressiveness of his platform speeches. His main target was Gladstone who he described as "the greatest living master of the art of personal advertisement". (27)

In May 1885 Churchill helped to orchestrate the defeat of Gladstone's Liberal government on a budget amendment opposing the increase in taxation and the absence of rate relief. Marquis of Salisbury became prime minister; Michael Hicks Beach was chancellor of the exchequer and leader of the House of Commons, while Stafford Northcote - held the largely nominal post of first lord of the Treasury. Churchill became secretary of state for India. The Conservative government was defeated on 26th January 1886. Although he won his seat in the subsequent General Election the Liberal Party returned to power. This caused Churchill financial problems who apparently remarked, "We're out of office, and they're economising on me." (28)

William Gladstone and the Liberals won the election with a majority of seventy-two over the Tories. However, the Irish Nationalists could cause problems because they won 86 seats. On 8th April 1886, Gladstone announced his plan for Irish Home Rule. Mary Gladstone Drew wrote: "The air tingled with excitement and emotion, and when he began his speech we wondered to see that it was really the same familiar face - familiar voice. For 3 hours and a half he spoke - the most quiet earnest pleading, explaining, analysing, showing a mastery of detail and a grip and grasp such as has never been surpassed. Not a sound was heard, not a cough even, only cheers breaking out here and there - a tremendous feat at his age... I think really the scheme goes further than people thought." (29)

The Home Rule Bill said that there should be a separate parliament for Ireland in Dublin and that there would be no Irish MPs in the House of Commons. The Irish Parliament would manage affairs inside Ireland, such as education, transport and agriculture. However, it would not be allowed to have a separate army or navy, nor would it be able to make separate treaties or trade agreements with foreign countries. (30)

Randolph Churchill advised Marquis of Salisbury to defend the Union by forming an alliance with the Spencer Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington and the other Liberals who opposed home rule. Churchill was the first prominent politician to advocate the creation of a "unionist party" - a coalition of Conservatives and unionist Liberals - which would maintain Britain's ties not only with Ireland but also with India and the empire. Churchill also decided to "play the Orange card" - to exploit the strong opposition of Ulster protestants to home rule.In a letter published in The Times, Churchill advocated enlightened unionism, but stated that if the Liberal government ignored the opposition to home rule, then "Ulster will fight, Ulster will be right". (31)

The Conservative Party opposed the measure. So did some members of the Liberal Party, led by Joseph Chamberlain, also disagreed with Gladstone's plan. Chamberlain main objection to Gladstone's Home Rule Bill was that as there would be no Irish MPs at Westminster, Britain and Ireland would drift apart. He added that this would be amounting to the start of the break-up of the British Empire. When a vote was taken, there were 313 MPs in favour, but 343 against. Of those voting against, 93 were Liberals. They became known as Liberal Unionists. (32)

William Gladstone responded to the vote by dissolving parliament rather than resign. During the 1886 General Election he had great difficultly leading a divided party. According to Colin Matthew: "So dedicated was Gladstone to the campaign that he agreed to break the habit of the previous forty years and cease his attempts to convert prostitutes, for fear, for the first time, of causing a scandal (Liberal agents had heard that the Unionists were monitoring Gladstone's nocturnal movements in London with a view to a press exposé)". (33) Churchill made an impassioned attack on Gladstone and his home-rule policy. He claimed that both the British constitution and the Liberal Party were being broken up merely "to gratify the ambition of an old man in a hurry". (34)

In the 1886 General Election the number of Liberal MPs fell from 333 in 1885 to 196, though no party gained an overall majority. William Gladstone resigned on 30th July. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, once again became prime minister. Queen Victoria wrote him a letter where she said she always thought that his Irish policy was bound to fail and "that a period of silence from him on this issue would now be most welcome, as well as his clear patriotic duty." (35)

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Salisbury formed a Conservative government and offered Churchill the leadership of the House of Commons. Churchill combined the leadership of the house with the post of chancellor of the exchequer and was thus second only to Salisbury in the ministerial hierarchy. It is claimed that Churchill acted as if he was the leader of the Conservative Party. (36) In a speech at Dartford, he warned Conservatives not to rest on their laurels since "Politics is not a science of the past; politics is a science of the future". He also declared that "The main principle and guiding motive of the Government in the future will be to maintain intact and unimpaired the union of the Unionist party'". (37)

Salisbury acknowledged Churchill's ability, but complained that he had a "wayward and headstrong disposition" and likened the cabinet to "an orchestra in which the first fiddle plays one tune and everybody else, including myself, wishes to play another" (38) When the journalist, Alfred Austin, alleged that Churchill wished to supplant the premier, Salisbury observed that "the qualities for which he is most conspicuous have not usually kept men for any length of time at the head of affairs". (39)

As chancellor of the exchequer Randolph Churchill was determined to be a reformer. His draft budget for 1887 proposed a radical overhaul of the tax system. "Churchill proposed to take 3d. off income tax, lower the duty on tea and tobacco, graduate the house and death duties, and double the government's rate support grant to local authorities. The scheme, though radical, was relatively kind to landowners and not socially redistributive." (40)

Churchill's priority as chancellor was to reduce the defence estimates below those of the last Liberal government. This was opposed by the secretary for war, William Henry Smith. The dispute came to focus on the £500,000 allocated for the fortification of ports and coaling stations. When Smith refused to give way, Churchill wrote to Salisbury, on 20th December 1886, stating his wish to resign from the government since he could not accept the defence estimates and did not expect support from the cabinet. (41) Churchill expected Salisbury to support him in this dispute. He was wrong and Salisbury, in his reply, supported Smith and accepted Churchill's resignation with "profound regret" (42)

Churchill then justified his resignation by linking his desire for economy with wider issues: "I remember the vulnerable and scattered character of the empire, the universality of our commerce, the peaceful tendencies of our democratic electorate, and the hard times, the pressure of competition, and the high taxation now imposed … it is only the sacrifice of a chancellor of the exchequer upon the altar of thrift and economy which can rouse the people to take stock of their lives, their position and their future." (43)

After leaving office, he admitted that he was physically exhausted and immediately went on a long vacation to the Mediterranean to recuperate. He experienced alternating phases of mania and euphoria. He was brought back from holiday in Canada in a straight-jacket. He died at the age of forty-five on 24th January 1895. His neurologist diagnosed his illness as syphilis, though it has recently been argued that his symptoms could have been caused by a tumour on the brain." (44)

Reputation

Winston Churchill decided to write a biography of his father. Churchill wrote to most of Lord Randolph's former colleagues in the Conservative Party and asked them for help with the book. Most of them refused as they were still angry by his recent defection to the Liberals. "Churchill chose to represent his father's career as a Greek tragedy. He portrays his father not as a man of ambition but as a man of principle who invented 'Tory Democracy' in the early 1880s... Lord Randolph's resignation is seen as a supreme act of self-sacrifice, undertaken for the cause of public economy and as a result of deep political differences between Lord Randolph and Lord Salisbury rather than personal incompatibility or clashing ambitions." (45)

John Charmley has argued convincingly that the book, Lord Randolph Churchill (1905) "established its author's reputation as an historian, but that was only half its work; the other half was to establish the suitability of its hero as a role-model for his son." (46) Lord Randolph is presented as the true heir of Benjamin Disraeli who had been destroyed by the reactionaries in the Tory Party. Wilfred Scawen Blunt wrote in his diary that Churchill was "playing precisely his father's game" and was now looking "to a leadership of the Liberal Party and an opportunity of full vengeance on those who caused his father's death." (47)

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Churchill (1970)

Lord Salisbury did not at once succeed to the full inheritance from Disraeli. The latter's death vacated the leadership in the House of Lords, but, as we saw earlier, when a party was in opposition and possessed no ex-Prime Minister still active in politics, it did not normally have a single leader for the party as a whole. The leader in the House of Commons was Sir Stafford Northcote, Chancellor of the Exchequer throughout Disraeli's administration. He had been elected at Disraeli's behest in 1876 when the Prime Minister took his earldom. The alternative candidate had been Gathorne Hardy, the Secretary of State for War. He was a tough debater and in many ways a stronger character, but Disraeli disapproved of his tendency to neglect the House in order to dine at home with his wife. Subsequently Disraeli regretted his decision to pass over him and on at least one occasion declared that he would not have selected Northcote if he had anticipated Gladstone's return to politics later that very year. He perceived Northcote's defects - a lack of vigour and an excessive respect for Gladstone whose private secretary he had in distant days once been. He would have liked to hand on both his own posts, i.e. the leadership of the whole party as well as the Lords, to Salisbury. Had he lived, he might have managed it...

Northcote was an ineffective leader, too "responsible", too courteous, too prosy - and it must be added too ill, for he had a grave affliction of the heart - to satisfy the more ardent Tories. The story of the way Lord Randolph Churchill undermined him is famous. He and the rest of the "Fourth Party" made a point of treating their leader with public mockery - Lord Randolph had a particularly irritating high pitched laugh which he used with much effect when Northcote spoke - and with private contempt which soon buzzed round the clubs. To his friends he described Northcote as "the Grand Old Woman", or alternatively as "the Goat". This was not for the reason which inspired people to give that soubriquet to Lloyd George - Sir Stafford's private life was impeccable - but because of the shape of his beard.

A word should be said about the Fourth party. It consisted of four clever frondeurs, Lord Randolph Churchill, Arthur Balfour, Sir Henry Drummond Wolff and J. E. Gorst. The first two need no introduction. Drummond Wolff, who was descended from Sir Robert Walpole on his mother's side, had been a diplomat and financier before entering parliament. He was more easy-going and older than the rest, being just on fifty. Not that any of them was as young as one tends to imagine. Lord Randolph, a younger son of the Duke of Marlborough and father of Winston Churchill, was thirty-one. Much of life was behind him when he first appeared as the very type of political jeunesse dorde. Arthur Balfour was a year older. Urbane, inscrutable, ironical, he remains a puzzle to posterity. He was Salisbury's nephew and he never quite entered into the spirit of the others.

(2) Randolph Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (5th July, 1880)

It was with considerable regret he found himself unable, owing to the late hour at which the right hon. and learned Gentleman the Attorney General for Ireland (Hugh Law) spoke on Tuesday, to offer some reply to his speech. He would remark generally, with respect to that speech, that there was one thing in it which filled him with surprise, and it was the tone of vindictive animosity towards landlords which pervaded the speech from the beginning to the end. He should really have been astonished had it been made by the hon. Member for the City of Cork (Mr. Parnell); but, coming as it did from one of the most able and respectable members of the Irish Bar, he was filled with considerable dismay. It occurred to him that if that speech faithfully represented the views of the Government, the Bill was not merely a temporary measure for the relief of Irish distress, but it was something widely different - it was the commencement of a campaign against landlords; it was the first step in a social war; it was an attempt to raise the masses against the propertied classes. And in connection with this view there was another feature 1641 in that speech which was most remarkable - that although there was going on at present an agitation of the most unmeasured nature on the Land Question, and although language was being used of a very singular kind at meetings which must have given the Attorney General for Ireland grave cause for anxiety and alarm, not a word, not a single syllable, not a hint, even, did the Attorney General give that could afford to the House a suspicion that he deprecated that agitation, or disapproved of that language. If the right hon. and learned Gentleman were to be judged by the promoters of that agitation from his speech, then those promoters had every right and reason to look on the Law Officers of the Crown in Ireland as their sympathizer, friend, and ally. He would leave the legal arguments with which his speech abounded to others who were more acquainted with the subtleties of lawyers than he was; but what the Attorney General said practically amounted to this: The landlords have had £1,250,000 from the State; how could they have the face to object to a measure for the relief of their tenantry? Amore ungenerous and misleading argument was never used in the House of Commons. What was the real position? At a most critical period of last year the late Government found themselves compelled to provide employment for the people in such a manner as to avoid the disasters which resulted from their employment upon public works in 1848. They sought the assistance of the Irish landlords, and offered them terms, which were not extravagantly in their favour, in order to secure the employment of the people and the development of the agricultural resources of the country. The landlords throughout the distressed districts came forward and accepted the terms of the Government; and thousands of people had been employed, and were being employed, by means of an outlay for which the landlords had rendered themselves liable. If the landlords had had any suspicion that what they had done would be turned against them in the way it had been by the right hon. and learned Gentleman, the House must not suppose that a six-pence of the loan would have been taken up.

(3) Boris Johnson, The Churchill Factor (2014)

As Winston Churchill used to tell his own children, he never had more than five conversations with his father - or not conversations of any length; and he always had the feeling that he didn't quite measure up to expectations.

He spent his youth in the certainty, relentlessly rubbed in by Randolph, that he must be less clever than his father. Randolph had been to Eton, whereas it was thought safer to send young Winston to Harrow - partly because of his health (the air of the hill being deemed better for his fragile lungs than the dank air by the Thames) but really because Harrow, in those days, was supposed to be less intellectually demanding…

And what kind of lesson did Randolph offer his son, about how to get on in Parliament? He displayed a shocking disloyalty to the Tories, and set up a group called the `Fourth Party', whose mission was to bash Gladstone but also to wind up the Tory Party leadership, in the form of Sir Stafford Northcote.

Randolph and chums called him "the goat", and after a while the goat could take it no more, and wrote to Randolph, begging him not to be such a tosser. Randolph wrote back, with blissful condescension, saying: "Since I have been in parliament I have always acted on my own account, and I shall continue to do so."

There, too, is young Churchill's cue: and when he gets to Parliament in 1900 he begins by setting up his own group of rebellious young Tories - called the Hughligans, in honour of Hugh Cecil, one of their number - and razzes the Tory high command, with Randolphian brio and insolence.

It was Randolph who showed the first and programmatic disdain for the very idea of party loyalty. As his son later described it, his father's preferred strategic position was "looking down on the Front Benches on both sides and regarding all parties in the House of Commons with an impartiality which is quite sublime".