On this day on 30th March

On this day in 1831 Thomas Babington Macaulay comments on parliamentary reform. He wrote to a friend about King William IV and the proposed 1832 Reform Act. "The royal assent was given yesterday afternoon to the Reform Bill. I rejoice at the course which the King has taken. It has had the effect that Lord Grey and the Whigs have all the honour of the Reform Bill and the King none of it. The King makes great concessions: but he makes them reluctantly and ungraciously. The people receive them without gratitude or affection. What madness - to give more to his subjects than any King ever gave, and yet to give in such a manner as to get no thanks."

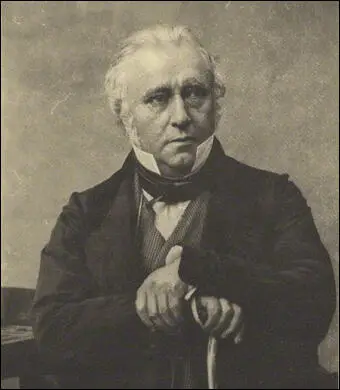

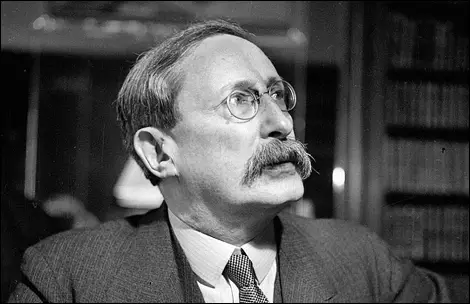

On this day in 1840 Charles Booth, the son of a wealthy businessman, was born in Liverpool. Booth's father was a Unitarian and head of the Lamport & Holt Steamship Company. When Booth was twenty-two his father died and took over the running of the company. Booth was an energetic leader and soon added a successful glove manufacturing concern to his expanding shipping interests.

In the 1860s Booth became interested in the philosophy of Auguste Comte, the founder of modern sociology. Booth was especially attracted to Comte's idea that in the future, the scientific industrialist would take over the social leadership from church ministers. One of the consequences of reading Comte was that Booth began to lose his religious faith.

In 1885 Charles Booth became angry about the claim made by H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation, that 25% of the population of London lived in abject poverty. Bored with running his successful business, Booth decided to investigate the incidence of pauperism in the East End of the city. He recruited a team of researchers that included his cousin, Beatrice Potter.

The result of Booth's investigations, Labour and Life of the People, was published in 1889. Booth's book revealled that the situation was even worse than that suggested by H. H. Hyndman. Booth research suggested that 35% rather than 25% were living in abject poverty. Booth now decided to expand his research to cover the rest of London. He continued to run his business during the day and confined his writing to evenings and weekends. In an effort to obtain a comprehensive and reliable survey Booth and his small team of researchers made at least two visits to every street in the city.

Beatrice Potter later recalled: "It is difficult to discover the presence of any vice or even weakness in him. Conscience, reason, and dutiful affect in, are his great qualities; what other characteristics he has are not to be observed by the ordinary friend. But he interests me as a man who has his nature completely under his control, and who has risen out of it, uncynical, vigorous and energetic in mind without egotism."

Over a twelve year period (1891 to 1903) Booth published 17 volumes of Life and Labour of the People of London. In these books Booth argued that the stare should assume responsibility for those living in poverty. One of the proposals he made was for the introduction of Old Age Pensions. A measure that he described as "limited socialism". Booth believed that if the government failed to take action, Britain was in danger of experiencing a socialist revolution.

Whereas many of his researchers, including Beatrice Potter, became socialists as a result of what they discovered while investigating poverty, Booth became more conservative in his views. Strongly opposed to trade unions, he was unhappy with the sympathetic treatment they had received from the the Liberal government that took power after the 1906 General Election. Booth now renounced his early support for the Liberal Party and joined the Conservative Party. Charles Booth died on 23rd November, 1916.

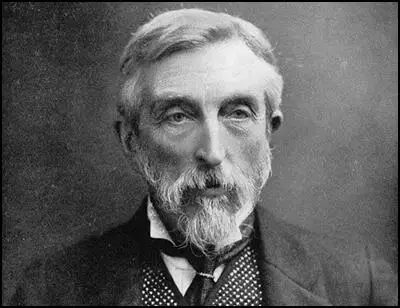

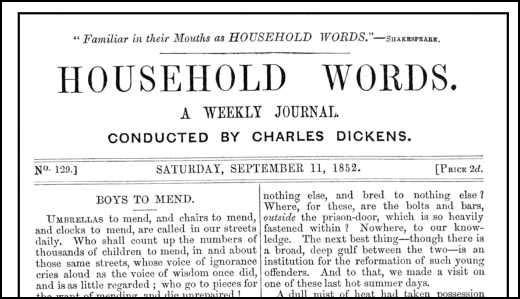

On this day in 1850 Charles Dickens published Household Words for the first time. Dickens became editor and William Wills, a journalist he worked with on the Daily News, became his assistant. One colleague described Wills as "a very intelligent and industrious man... but rather too gentle and compliant always to enforce his own intentions effectually upon others." Dickens thought that Wills was the ideal man for the job. He commented that "Wills has no genius, and is, in literary matters, sufficiently commonplace to represent a very large proportion of our readers".

Dickens rented an office at 16 Wellington Street North, a small and narrow thoroughfare just off the Strand. Dickens described it as "exceedingly pretty with the bowed front, the bow reaching up for two stories, each giving a flood of light." Dickens announced that aim of the journal would be the "raising up of those that are down, and the general improvement of our social condition". He argued that it was necessary to reform a society where "infancy was made stunted, ugly, and full of pain; maturity made old, and old age imbecile; and pauperism made hopeless every day." He added that he wanted London to "set an example of humanity and justice to the whole Empire".

Dickens planned to serialise his new novels in the journal. Another project was the serialisation of A Child's History of England. He also wanted to promote the work of like-minded writers. The first person he contacted was Elizabeth Gaskell. Dickens had been very impressed with her first novel, Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life (1848) and offered to take her future work. She sent him Lizzie Leigh, a story about a Manchester prostitute, which appeared in the first issue, on 30th March 1850.

After lengthy negotiations it was agreed that Charles Dickens would have half share in all profits of Household Words. Bradbury & Evans to have one quarter, John Forster and William Henry Wills, one eighth each. Whereas the publisher was to manage all the commercial details, Dickens was to be in sole charge of editorial policy and content. Dickens was also paid £40 a month for his services as editor and a fee was agreed for any articles and stories published by the journal. The first edition of the journal appeared on 30th March, 1850. It contained 24 pages and cost twopence and came out every Wednesday. On the top of each page were the words: "Conducted by Charles Dickens". All contributions were anonymous but when his friend, Douglas Jerrold, read it for the first time, he commented that it was "mononymous throughout". Elizabeth Gaskell described the content as "Dickensy".

On 12th April 1850 Dickens wrote to his close friend, Angela Burdett Coutts: "The Household Words I hope (and have every reason to hope) will become a good property. It is exceedingly well liked, and goes, in the trade phrase, admirably. I daresay I shall be able to tell you, by the end of the month, what the steady sale is. It is quite as high now, as I ever anticipated; and although the expenses of such a venture are necessarily very great, the circulation much more than pays them, so far. The labor, in conjunction with Copperfield, is something rather ponderous; but to establish it firmly would be to gain such an immense point for the future (I mean my future) that I think nothing of that."

Claire Tomalin wrote that with the journal: "He set out to raise standards of journalism in the crowded field of periodical publication and, by winning educated readers and speaking to their consciences, to exert some influence on public matters; and to this end he himself wrote on many social issues - housing, sanitation, education, accidents in factories, workhouses, and in defence of the right of the poor to enjoy Sundays as they chose."

The journal was a great success and it was soon selling 39,000 copies. Peter Ackroyd has argued: "It was nothing like such serious journals as The Edinburgh Review - it was not in any sense intellectual - but rather took its place among the magazines which heralded or exploited the growth of the reading public throughout this period... Since this was not the cleverest, the most scholarly or even the most imaginative audience in Britain, Household Words had to be cheerful, bright, informative and, above all, readable." In its first year Dickens earned an extra £1,700 from the journal and in the second year of trading, £2,000.

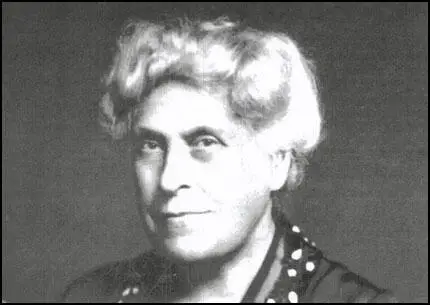

On this day in 1882 Melanie Reizes, the daughter of Moriz Reizes and Libussa Deutsch Reizes, was born in Vienna. Her father was born into an orthodox Jewish family but studied to become a doctor against his parents' wishes. He spoke ten languages and was extremely well read.

Her mother was the grand-daughter of a rabbi. Moriz met her while they were staying in the same boardinghouse. He immediately fell in love with this "educated, witty, and interesting" young woman, with her fair complexion, fine features, and expressive eyes". They married in 1875.

Melanie was the youngest of four children, Emilie born in 1876, Emmanuel in 1877 and Sidonie in 1878. The family were in financial difficulties when she was born and her mother opened a shop that sold plants. Libussa was so busy that she was unable to breast feed her. She was handed over to a wet-nurse who fed her on demand, though the older children had all been fed by their mother.

Melanie claims that her father made no secret of his preference for Emilie, who together with Emmanuel, teased her for her ignorance. However, her eight-year-old sister, Sidonie, did take an interest in her and taught her reading and arithmetic during her long illness with scrofula (a form of tuberculosis). Although she survived, her sister, Sidonie, died of the disease in 1886. Janet Sayers, the author of Mothers of Psychoanalysis (1991), claims that this might have "contributed to Melanie's life-long depression."

Melanie later wrote: "I have a feeling that I never entirely got over the feeling of grief for her death. I also suffered under the grief my mother showed, whereas my father was more controlled. I remember that I felt that my mother needed me all the more now that Sidonie was gone, and it is probable that some of the spoiling was due to my having to replace that child."

In 1891, Emmanuel, aged 14, praised and corrected a poem she had written, he was "my confidant, my friend, my teacher". He taught her Latin and Greek in order to enable her to attend the Gymnasium and encouraged her to have her writing published. "He took great interest in my development and I knew that, until his death, he always expected me to do something great, although there was really nothing on which to base it... He seemed to me superior in every way to myself, not only because at nine or ten years of age, he seemed quite grown-up, but also because his gifts were so unusual... He was a self-willed and rebellious child and, I think, not sufficiently understood. He seemed at loggerheads with his teachers at the gymnasium, or contemptuous of them, and there were many controversial talks with my father."

Emmanuel introduced Melanie to the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche, Arthur Schnitzler and Karl Kraus, all radical thinkers who challenged conventional morality. She also mixed with her brother's friends and it is claimed that four of these young men wanted to marry her. However, she rejected this idea and planned to study medicine like her father but to specialise in psychiatry. Her last years at school, under the influence and encouragement of her brother, were years in which she felt "gloriously alive".

Melanie's plans to go to university ended when her father died in April 1900. This was followed by the death of Emmanuel from a heart-attack. She now agreed to marry Arthur Stephan Klein, a second cousin and the son of Jacob Klein, a successful businessman. They married in 1903. Klein, an engineer, worked for a number of companies in different parts of Europe and was rarely at home.

Melanie's marriage was unhappy from the beginning. "I threw myself as much as I could into motherhood and interest in my child. I knew all the time that I was not happy but saw no way out." She told a friend many years later that he was having affairs from the first years of her marriage. Melanie Klein gave birth to her daughter, Melitta Klein in 1904. This was followed by two sons, Hans in 1907 and Erich in 1914. She was forced to stay with her husband because she had no means of supporting them on her own.

In 1914 Melanie Klein went into analysis with Sandor Ferenczi, an eminent Hungarian doctor, who was a member of a group of doctors who were followers of a group led by Sigmund Freud. Another member of the group was Hanns Sachs who said he was "the apostle of Freud who was my Christ". Another member said "there was an atmosphere of the foundation of a religion in that room. Freud himself was its new prophet... Freud's pupils - all inspired and convinced - were his apostles." Another member remarked that the original group was "a small and daring group, persecuted now but bound to conquer the world".

On Frenczi's recommendation, Melanie Klein read Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams. Freud argued that "If you inspect the dreams of very young children, from eighteen months upwards, you will find them perfectly simple and easy to explain. Small children always dream of the fulfillment of wishes that were aroused in them the day before but not satisfied." The dreams of adults are more difficult to explain. "Certainly the most satisfactory solution of the riddle of dreams would be to find that adults' dreams too were like those of children-fulfilments of wishful impulses that had come to them on the dream-day. And such in fact is the case. The difficulties in the way of this solution can be overcome step by step if dreams are analysed more closely."

Freud admitted that in most cases adult dreams could not look more unlike the fulfillment of a wish. "And here is the answer. Such dreams have been subjected to distortion; the psychical process under lying them might originally have been expressed in words quite differently. You must distinguish the manifest content of the dream, as you vaguely recollect it in the morning and laboriously (and, as it seems, arbitrarily) clothe it in words, and the latent dream thoughts, which you must suppose were present in the unconscious. This distortion in dreams is the same process that you have already come to know in investigating the formation of hysterical symptoms. It indicates, too, that the same interplay of mental forces is at work in the formation of dreams as in that of symptoms. The manifest content of the dream is the distorted substitute for the unconscious dream-thoughts and this distortion is the work of the ego's forces of defence - of resistances."

Sigmund Freud gives the example of a woman patient who had a dream that she was strangling a little white dog. The doctor asked her if she had a particular grudge against anyone. She said yes she had, and added that it was against her sister-in-law. She went on, "She is trying to come between my husband and myself". She was encouraged to talk more about this conflict and after a while she remembered that in a recent argument she described her as "a dog that bites". She also pointed out that her sister-in-law had a remarkably pale complexion. The patient now realised the meaning of the dream.

Freud argued that a woman who dreams that she wants to give a supper but cannot find the food in the shops, is satisfying her wish to refrain from inviting a friend of whom her husband is fond and she is jealous. In another case a woman dreams that her fifteen-year old daughter is lying dead in a box is satisfying her earlier wish for an abortion when pregnant. Freud argued that in these dreams the experience of anxiety is the distorted satisfaction of a sexual desire. He then went on to say that the accuracy of this statement "has been demonstrated with ever increasing certainty".

In The Interpretation of Dreams Freud explained the now famous Oedipus complex. "Being in love with the one parent and hating the other are among the essential constituents of the stock of psychical impulses which is formed in childhood and which in children destined to grow up neurotic is of such importance in determining their symptoms. The discovery is confirmed by a legend that has come down to us from classical antiquity... What I have in mind is the legend of King Oedipus and Sophocles' drama which bears his name."

Melanie Klein also read Freud's Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. In the book Freud put together, from what he had learned by analyses of patients and other sources, all he knew about the development of the sexual instinct from its earliest beginnings in childhood. Freud provided "the foundation for his theory of neuroses, the explanation of the need for repression and the source of emotional energy underlying conscious and unconscious drives and behaviour which he named libido."

Klein began to make observations on her youngest son, Erich, and she was encouraged to carry on when Sandor Ferenczi told her she had a gift for psychoanalytical understanding. She was determined to allow her young son's mind "freedom from unnecessary prohibitions and distortions of the truth". An atheist, Klein decided she did not want to teach him that there was a God. She also was straightforward and truthful with him about sex. This at the time was extremely radical. The results of her experiment was described in a paper she gave to the Budapest Psychoanalytical Society in 1919, entitled The Development of a Child: The Influence of Sexual Enlightenment and Relaxation of Authority on the Intellectual Development of Children. It was published as an article two years later.

Although her son, Erich, was only five-years-old at the time, she found ways of talking to him about sex. At first he did not want to know, but after she told him stories about the sex life of animals he began to show interest. He responded by telling his mother stories where he made symbolic use of the objects around him. He ran his toys over her body, saying they were climbing mountains. He talked of what babies are made of and said he wanted to make babies with his mother. Erich told another story "in which the womb figured as a completely furnished house, the stomach particularly was very fully equipped and was even possessed of a bath-tub and a soap-dish."

Melanie Klein argued that this form of education changed him from being somewhat backward to "almost precocious". His attitude towards his parents changed: "His games as well as his phantasies showed an extraordinary aggressiveness towards his father and also of course his already clearly indicated passion for his mother. At the same time he became talkative, cheerful, could play for hours with other children, and latterly showed such a progressive desire for every branch of knowledge and learning that in a very brief space of time and with very little assistance, he learnt to read."

Klein also analysed her older children. Hans was forced to stop seeing a girl older than himself because of the "identification he was making with the phantasy of his mother as a prostitute". In her article, A Contribution to the Psychogenesis of Tics she argued that "the turning away from the originally loved but forbidden mother had participated in the strengthening of the homosexual attitude and the phantasies about the dreaded castrating mother."

Klein now forced Hans to break off a homosexual relationship with a school friend. "It must have seemed to the boy that he had no area of privacy from his mother, who knew the innermost secrets of his soul. His tic and related homosexual problems she repeatedly links to his sense of inferiority to his father. Arthur Klein was deeply suspicious of psychoanalysis, which he saw as driving a wedge between him and his son, and his wife's obsession with it as a disruptive intrusion in the family."

Melanie Klein considered herself as the world's first child analyst. However, that title went to Hermine Hug-Hellmuth. A former schoolteacher, she published The Nature of the Child's Soul (1913) and A Young Girl's Diary (1919). At the International Congress in The Hague in 1920, she reported on her early efforts in her paper On the Technique of the Analysis of Children. Her work was based on observation and analysis of children's behavior and on the possibility of applying psychoanalytic theory to education and the psychology of children. This included analysing her nephew, Rudolf Otto Hug. The illegitimate child of her half-sister Antoine, he had been raised by Hug-Hellmuth since the death of his mother.

Melanie Klein went to meet Hug-Hellmuth but did not find her very helpful, possibly because she found her a threat. "Dr. Hug-Hellmuth was doing child analysis at this time in Vienna, but in a very restricted way. She completely avoided interpretations, though she used some play material and drawings, and I could never get an impression of what she was actually doing, nor was she analysing children under six or seven years."

Hug-Hellmuth actually warned against analysis for children if it touched their deepest feelings. She suggested that it is dangerous to uncover too many of children's negative and aggressive feelings towards their parents. Hug-Hellmuth was not only afraid of alienating parents by exposing to children their aggression towards their parents, but she also wanted the children to have good and friendly feelings towards themselves.

Melanie left her children with her in-laws in Rosenberg in Slovakia and moved to Germany and became a member of Berlin Psychoanalytical Society in 1922. Along with Anna Freud she was now seen as one of the pioneers of child psychology. Klein by this time had become dissatisfied with the results of her analysis with Sandor Ferenczi and asked Karl Abraham to take her into analysis. She said later that it was her brief analysis with Abraham which really taught her about the practice and theory of analysis.

While in Germany she met Alix Strachey, the wife of Freud's translator James Strachey. The two women became close friends: "She (Melanie) was frightfully excited and determined to have a thousand adventures, and soon infected me with some of her spirits… she's really a very good sort and makes no secret of her hopes, fears and pleasures, which are of the simplest sort. Only she's got a damned sharp eye for neurotics."

Melanie Klein also worked for the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute. Others involved included Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Ernst Simmel, Hanns Sachs, Karen Horney, Edith Jacobson and Wilhelm Reich. The institute reflected the socialist sentiments widely held by Berlin intellectuals at the time. From the very beginning the institute provided free analytic treatment, often to more than a hundred patients. Later, it provided inpatient treatment to about thirty severely disturbed men who were suffering from the consequences of the First World War. Although Sigmund Freud was not directly involved praised the institute for "making our therapy accessible to the great numbers of people who suffer no less than the rich from neurosis, but are not in a position to pay for treatment."

Ernst Simmel, who succeeded Abraham as institute president, took pride that the clinics free treatment did not differ in the least from that of patients paying high fees. "All patients are... entitled to as many weeks or months of analysis as his condition requires". In this way the Berlin Institute was fulfilling social obligations incurred by society, which "makes its poor become neurotic and, because of its cultural demands, lets its neurotics stay poor, abandoning them to their misery."

Klein was disappointed by Simmel's election as she found Abraham as more supportive of her ideas. Abraham was described as "the very best president I ever met in my life. He was simply magnificent. Fair and absolutely firm. No nonsense. And kept the thing very well in hand. Again, he had his limitations. He didn't like fantasy very much. He didn't have much fantasy himself, but he was very much down to earth, excellent clinician, perfect chairman, and really a fair man."

Karen Horney was so impressed with her work that she decided that the girls' education should be supplemented with a course of psychoanalytic treatment with Melanie Klein. Brigitte, who was fourteen, refused to go for analysis. Marianne, was twelve and more complaint, attended faithfully for two years but developed strategies that kept Klein's interpretations to a minimum. Renate, who was only nine, tried to cooperate but disliked the talk about sexual matters. Later, Horney, psycho-analysised Melitta.

Melitta trained at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute, before marrying Walter Schmideberg in 1924, another psychoanalyst, who was fourteen years her senior. At the time Schmideberg was a friend of Sigmund Freud and Klein's biographer, Phyllis Grosskurth, claims she had "encouraged the marriage for the reflected prestige it would give her". However, it was not long before Klein turned against Melitta's new husband. These family rows, mainly concerned Schmideberg's drinking problems. The following year he was treated for drug addiction at Sanatorium Schloss Tegel.

On the night of 8th September, 1924, Hermine Hug-Hellmuth was murdered by her eighteen-year-old nephew, whom she had brought up. According to Rudolf Otto Hug, his aunt's writings contained many observations of him and he testified at his trial that she had attempted to psychoanalyze him. After his trial he was sentenced to twelve years in prison. After being released from prison, he attempted to get restitution from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association, as a victim of psychoanalysis.

This murder had a tremendous impact on the psychoanalytic movement. Members of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute became increasingly critical of Melanie Klein's theories. They accused her of being "feeble-minded about theory" and her "nursery talk embarrassing and ridiculous". Some of the members suggested that "child analysis was positively dangerous". In May 1925, Karl Abraham became seriously ill and was no longer able to have her as his patient. After his death in December, she began to consider the possibility of leaving Germany.

In September, 1926, Melanie Klein, at the age of 38, accepted the invitation of Ernest Jones, to analyse his children in London. She lived in a maisonette near the Institute of Psychoanalysis in Gloucester Place. Her practice soon included not only Jones's children and wife but also six other patients. She now decided to settle permanently in England, a place that she described as "her second motherland".

Klein's daughter, Melitta Schmideberg, also came to live in England. She gave several lectures on child psychology. This included Criminal Tendencies in Normal Children (1927), Personification in the Play of Children (1929) and The Importance of Symbol-Formation in the Development of the Ego (1930). Phyllis Grosskurth claims that these papers contain "a medley of diverse ideas, a reflection of the creative thinking that had been released in her with a congenial atmosphere".

Over the next few years Melanie Klein wrote several articles where she questioned several of Sigmund Freud's theories. This included the claim that the Oedipus conflict began long before Freud had thought. Freud thought that there was a period in which children loved their mothers without conflict. Klein argued this was not so and believed that even very small babies had to cope with conflicting feelings of love and hatred.

Klein also questioned Freud's account of creativity. He attributed art to sublimation of individual instinct whereas Klein explained it as reflecting our relations with others, in the first place with the mother. In a British Society talk in May 1929 she illustrated this theme by reference to the work of the Swedish artist, Ruth Kjär. Klein quoted from Kjär's biographer, who argued that she suffered bouts of depression until she started painting pictures. "Klein thereby inaugurated a new trend in art and literary criticism focusing on the maternal and reparative aspects of creativity."

Supporters of Sigmund Freud became hostile towards Melanie Klein. This included Ernest Jones and Edward Glover, both senior figures in the British Psycho-Analytical Society. In 1933, Klein's daughter, Melitta Schmideberg decided to enter analysis with Glover. This resulted in her deciding that she "had been in a state of neurotic dependence on her mother" and that if a "state of amicability was to be maintained, it could exist only if Klein recognized her not as an appendage but as a colleague on an equal footing". In late 1933 it was apparent to other members of the Society that Glover and Schmideberg, had joined forces in a campaign to embarrass and discredit Melanie Klein. Schmideberg, later wrote: "Edward Glover and I agreed to ally to fight".

In a letter she wrote to her mother at this time explaining her thoughts on their relationship. "You do not take it enough into consideration that I am very different from you. I already told you years ago that nothing causes a worse reaction in me than trying to force feelings into me - it is the surest way to kill all feelings. Unfortunately, you have a strong tendency towards trying to enforce your way of viewing, of feeling, your interests, your friends, etc. onto me. I am now grown up and must be independent; I have my own life, my husband; I must be allowed to have interests, friends, feelings and thoughts which are different or even contrary to yours. I do not think that the relationship with her mother, however good, should be the centre of her life for an adult woman. I hope you do not expect from my analysis that I shall again take an attitude towards you which is similar to the one I had until a few years ago. This was one of neurotic dependence. I certainly can, with your help, retain a good and friendly relationship with you, if you allow me enough freedom, independence, and dissimilarity, and if you try to be less sensitive about several things."

Members of the British Psycho-Analytical Society tended to take the side of Melanie Klein against the attacks of her daughter. Melitta believed that this undermined her own status in the organisation: "I always felt that the main objection was that I had ceased to toe the Kleinian line (Freud by now was regarded as rather out-dated). Mrs. Klein had postulated psychotic phases and mechanisms in the first months of life, and maintained that the analysis of these phases was the essence of analytic theory and therapy. Her claims were becoming increasingly extravagant, she demanded unquestioning loyalty and tolerated no disagreement."

In April 1934, Hans Klein died while walking in the Tatra Mountains. It is believed that the path suddenly crumbled away beneath him and he plunged down the side of a precipice. Melanie was so distraught that she was unable to leave London and a close friend maintained that Hans's death was a source of grief for the rest of her life. Melitta's immediate reaction was that it had been suicide. At a conference in November she commented: "Anxiety and guilt are not the only emotions responsible for suicide. To mention only one other factor, excessive feelings of disgust brought about, for example, by deep disappointments in persons loved or by the break-down of idealizations prove frequently an incentive towards suicide."

Freud attributed self-reproach in depression to hatred of others internalized in imagination within the self. Klein disagreed with Freud and suggested that the main reason for depression to love of others and despair at feeling unable to restore the harm done by hatred of them. Whereas Freud believed depression is rooted in self-love and attachment to others. Klein rejected this idea and argued that depression does not stem from self-love but from concern for others. "Suicide in such cases involves a last-ditch attempt to preserve those one loves within the self by destroying the bad."

It has been argued that Klein was using her own experience to explain depression. As a child she suffered from chronic depression as a result of "the preference of her father for Emilie; the death of Sidonie; her anguish and guilt over Emanuel; her breakdown following her mother's death; her ambivalent feelings towards Arthur Klein; her devastation after Abraham's death". This was followed by Han's death and "Melitta's treachery".

Klein built up a group of loyal followers but like Sigmund Freud, she could be ruthless in casting off those who expressed doubts about her theories. Hanna Segal pointed out: "Although she was tolerant, and could accept with an open mind the criticisms of her friends and ex-pupils, whom she often consulted, this was so only so long as one accepted the fundamental tenets of her work. If she felt this to be under attack she could be very fierce in its defence. And if she did not get sufficient support from those she considered her friends, she could grow very bitter, sometimes in an unjust way."

In May 1936, Ernest Jones attacked Melanie Klein in a paper delivered to the Vienna Society. He claimed that Freud had provided the "scaffolding" and that they might see "considerable changes in the course of the next twenty years ago". However, he warned of those, who like Klein, who had succumbed to "the temptation to a one-sided exaggeration of whatever elements may have seized her interest".

On 17th February, 1937, Melitta Schmideberg continued her strident campaign against her mother when she delivered the paper, After the Analysis - Some Phantasies of Patients, that was delivered to the British Society. Joan Riviere wrote to James Strachey: "Melitta read a really shocking paper on Wednesday personally attacking Mrs. Klein and her followers and simply saying we were all bad analysts - indescribable."

Melanie Klein was in poor health and in July 1937 she underwent gall bladder surgery. Afterwards she went to live with her younger son Erich and his wife, Judy, who was at the time pregnant with their first child. (As a result of the level of anti-semitism in England he changed his name to Eric Clyne in 1937).

In the summer of 1938 Klein gave a paper to the Paris Congress entitled Mourning and its Relationship to the Manic-Depressive States, where she criticised Freud's views on depression which he believed was rooted in self-love. Klein suggested that grief involves recognizing both external and internal loss. "Loss does not so much initiate internalization of the other as Freud claimed. Rather it painfully disrupts internalization processes began in relation to the mother in infancy."

Melanie Klein met Virginia Woolf at a meeting of the British Psycho-Analytical Society. That night Woolf recorded in her diary her impression of Klein. "A woman of character and force some submerged - how shall I say - not craft, but subtlety, something working underground. A pull, a twist, like an undertow: menacing. A bluff grey haired lady, with large bright imaginative eyes."

Sigmund Freud and most of his family, including Anna Freud, arrived in London on 6th July, 1938, after the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany. (53) Melanie Klein sent him a letter expressing the wish to call on him as soon as he was settled. He replied with a brief note saying that he hoped to see her in the near future. An invitation failed to materialize, although her daughter, Melitta Schmideberg, was a frequent visitor.

Edward Glover, the scientific secretary of the British Psycho-Analytical Society, found himself increasingly opposed to the innovations and influence of Melanie Klein. For several years he tried to oust the Kleinians as a group within the Society. The problem increased with Klein's supporters who arrived in England from Austria and Germany, fleeing from Adolf Hitler. This included people such as Hanna Segal, Paula Heimann, Herbert Rosenfeld, Nelly Wollfheim and Eva Rosenfeld. By 1938 one-third of its members were from the continent. She also had the support of British members such as Susan Sutherland Isaacs, Joan Riviere, John Rickman, Donald Winnicott and Clifford M. Scott.

However, Ernest Jones, protected Klein from Glover. In March 1939 she wrote to Jones thanking him for his help. "You have created the movement in England and carried it through innumerable difficulties and hardships to its present position... Now, I want to thank you for your personal friendship, and for your help and encouragement in what is of infinitely greater importance to us both than personal feelings - namely our work. I shall never forget that it was you who brought me to England and made it possible for me to carry out, and develop, my work in spite of all opposition."

Anna Freud joined with Glover in the attacks on Klein arguing at a meeting of the British Psycho-Analytical Society Training Committee meeting that "Mrs. Klein's work is not psycho-analysis but a substitution for it. The reason she gave for this opinion was that Mrs. Klein's work differs so greatly in theoretical conclusions and in practice from what they know to be psychoanalysis... Dr. Glover said that her work may either turn out to be a development of psycho-analysis or a deviation from it... Regarding the body of knowledge which should be taught to candidates, he said that controversial contributions should be excluded, referring to Mrs. Klein's work."

Melanie Klein's daughter, Melitta Schmideberg, was also highly critical of the Kleinian group. At one meeting, on 13th May 1942: "Melitta's shrill accusations, based on innuendo and gossip, had been distressing and embarrassing; but Glover's thundering rhetoric in leveling the gravest of charges against the Kleinian group left everyone at the meeting shaken. Glover essentially accused one group of trying to insinuate its way into power through the training of candidates; and if the situation were allowed to continue, within a very few years the British Society would be entirely dominated by the Kleinians." Melanie Klein commented that her supporters were made to look like "a forbidden sect doing some harmful work, which should be prevented from spreading."

Ernest Jones condemned the behaviour of Schmideberg and Glover and that Klein had good cause to bring a libel action against them. Anna Freud agreed and Klein reported to Susan Sutherland Isaac that: "She (Anna) is inclined to regard Melitta's attacks more in the way of a naughty child, and certainly underrates the disruptive effect on the Society which was - and here she is quite right - only so bad because the Society did not know how to deal with it."

Glover argued that "in the six years up to 1940 every training analyst appointed (5 in all) was an adherent of Mrs. Klein". Sylvia Payne carried out research into these claims and wrote to Klein about what she found: "I have studied Glover's speech. He says that there are 8 or 9 of your adherents among training analysts. The following are the actual names. Klein, Riviere, Rickman, Isaacs, Winnicott, Scott (control of child analysis and lectures). To these names he must be adding Wilson and Sheehan-Dare (they accepted many Kleinian ideas, but refused to be described as adherents of anyone). I propose to say that his figures are open to argument."

Edward Glover was outraged by a January 1944 suggestion that the teaching of the organization should cover Klein's controversial ideas. He now resigned, complaining that the Society was hopelessly "women ridden". In a letter to Sylvia Payne he explained his decision: "I have now simply exercised the privilege of withdrawing from the Society (a) because its general tendency and training has become unscientific and (b) because it is becoming less and less Freudian and has therefore lapsed from its original aims."

Glover attempted to persuade Anna Freud to leave the British Psycho-Analytical Society. Phyllis Grosskurth argued that "Glover lacked psychological insight and an understanding of the strength of Anna Freud's inflexibility. She would not allow herself, Freud's daughter, to be pushed out of the Society and branded as a schismatic. She sometimes said that she stayed in because she was grateful to Jones for bringing her family to England, but it is possible that she also felt that she could work things to her own advantage if she played her cards right."

Negotiations continued for two years before an agreement was reached. On 5th November, 1946, a scheme of training was arranged which incorporated both the ideas of Sigmund Freud and Melanie Klein. "It is disturbing to accept that highly intelligent, well-educated people could succumb to the hysteria that swept through the British Society for some years. But one must realize that all human beings, even psychoanalysts, are subject to the same pressures; when engulfed in groups, they exhibit envy, anger, and competitiveness, whether the group be a trade union or a synod of bishops. The fact that the British Society did not split is, in the view of many members, evidence both of British hypocrisy and of British determination to compromise."

In 1955 Melanie Klein published a paper entitled, Some Theoretical Conclusions Regarding the Emotional Life of the Infant. She argued that the child seeks both enviously to spoil good things in the mother, and greedily to expropriate and devour and destroy them within itself. Such greed and envy, she insisted, begins not with envy of the father's penis as symbol of self-esteem as Freud had claimed. It begins with envy of the mother's breast. She agreed with Karen Horney that both boys and girls envy the breast.

Klein believed that breast-feeding played an important role in the relationship between the mother and child: "A really happy relationship between mother and child can be established only when nursing and feeding the baby is not a matter of duty but a real pleasure to the mother. If she can enjoy it thoroughly, her pleasure will be unconsciously realized by the child, and this reciprocal happiness will lead to a full emotional understanding between mother and child… it is important that a mother should recognise that her child is not a possession and that, though he is so small and utterly dependent on her help, he is a separate entity and ought to be treated as an individual human being; she must not tie him too much to herself, but assist him to grow up to independence."

In 1957 Klein published Envy and Gratitude. In the book she rejected the idea of "penis envy" and instead suggested that men suffered from "breast envy". She argued: "Experience has taught me that the first object of envy is the nourishing breast, as the child feels that the breast possesses all that he desires, has an unlimited amount of milk and love but holds it for his enjoyment. This feeling increases the child's resentment and hatred, and consequently disturbs his reationship with the mother."

Freudians complained that Klein's method threatened to "imprison both patient and analysist in a matriarch world". Julia Segal argues that there was another major reason for the attacks she received: "Many people opposed and still oppose Klein's view that a small baby may have powerful feelings of aggression not only towards its mother in general but even towards her breast at an age when the baby is too small to have a perception of her as a whole person... Teaching about Klein for many years, I have found that the idea that the small baby has feelings of hatred and aggressiveness from the beginning is extremely unpalatable, particularly among those; who like to see the baby as the innocent victim of a cruel world. Those who have given birth to babies themselves tend in my experience to have a view more accepting of Klein's. The idea that a baby has only good, loving feelings towards its mother does not really stand up to nights pacing backwards and forwards with a baby who is screaming and will not be comforted, or who sometimes turns away from the breast and screams for no apparent reason. Clearly, there may be a reason, but it is not a simple matter of being a bad parent."

Melanie Klein found this criticism difficult to take and the main result was an intense feeling of loneliness. This was the subject of her final paper. "Loneliness is not the objective situation of being deprived of external companionship. I am referring to the inner sense of loneliness - the sense of being alone regardless of external circumstances, of feeling lonely even when among friends or receiving love. This state of internal loneliness, I will suggest, is the result of a ubiquitous yearning for an unattainable perfect internal state. Such loneliness, which is experienced to some extent by everyone, springs from paranoid and depressive anxieties which are derivatives of the infant's psychotic anxieties. These anxieties exist in some measure in every individual but are excessively strong in illness; therefore loneliness is also part of illness, both of a schizophrenic and depressive nature."

Melanie Klein died on 22nd September 1960. Melitta Schmideberg did not attend the funeral and instead gave a lecture in London wearing red boots.

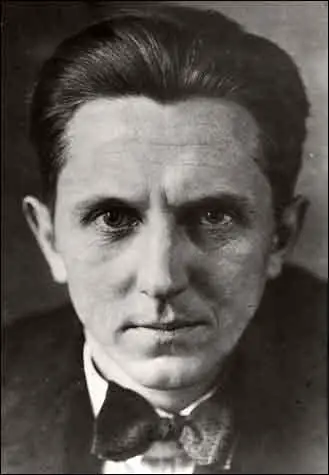

On this day in 1883 Jo Davidson was born in New York City. He worked under Hermon Atkins MacNeil before moving to Paris to study sculpture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1907. His realistic busts soon gained him commissions from wealthy patrons such as Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

Davidson lived in Greenwich Village where he became a close friend of Lincoln Steffens and other writers and artists. Some of his early commissions included George Bernard Shaw, Woodrow Wilson and Joseph Conrad. During the First World War he made busts of General Ferdinand Foch and Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau.

Peter Hartshorn has argued that he attended the Versailles Peace Conference in 1918: "He headed to Paris to take advantage of the historic occasion by making busts of the Allied leaders gathered there. Armed with letters of introduction to French Marshall Ferdinand Foch and Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, Davidson had high hopes." Over the next few weeks he produced busts of John J. Pershing, Arthur Balfour, Edward House and Bernard Baruch.

After the First World War Davidson moved to Paris where he associated with Lincoln Steffens, Ezra Pound, William Christian Bullitt, Louise Bryant, Ella Winter, John Dos Passos, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Ford Madox Ford and Gertrude Stein. According to Justin Kaplan, the author of Lincoln Steffens: A Biography (1974): "Despite their sophistication and internationalism, they belonged to a straggling, authentically native succession of grass-roots radicals (of the right as well of the left) and cracker-barrel sages, men with a populist hunger for drastic solutions and an inclination to spend their time and spirit cussing out the government and the banks while awaiting the arrival of the messiah."

Ella Winter was the wife of Lincoln Steffens and they spent a great deal of time with Davidson and his wife Yvonne, a dress designer. In her book, And Not to Yield (1963), she wrote: "We were almost always with Jo and Yvonne. The Davidsons appreciated food in the French manner, and discussed and selected restaurants all over Paris for their specialties. Their thrill at discovering a new bistro, or a sauce at Chez Pierre or Le Commerce, was a curious experience for me, with my London memories of three-and-sixpenny ABC lunches, and I must confess I was at first somewhat dismayed at so much fuss about mere food."

Steffens wrote in his memoirs, Autobiography (1931): "Jo Davidson is the only artist I have met who was consciously in the stream of life as I knew it. The others, certainly the young Americans in Paris, had been in the water, some of them had been nearly drowned by the flood of the war, but they saw and felt only the waves that broke over them.... Jo Davidson had been at the front, though only as a correspondent, but he never dwelt on those experiences. Like Jack Reed, he saw and felt the big forces that had done it once to us and might do it again... His art saved the sculptor. Busting generals, statesmen, financiers, he talked to them, and he listened to them, and so saw the war and the peace from the perspective of headquarters, the capitals and the markets... I have heard him say that the war had no influence upon art, only on some of its themes. It had turned him from nudes and decorations to heads, mostly of great men, and he often regretted that."

Jo Davidson was a political activist and was chairman of the Independent Citizens Committee of Artists, Scientists, and Professionals (ICCASP), a group that supported the policies of President Franklin Roosevelt. An opponent of the Cold War policies of Harry S. Truman, he joined the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA). Other members included Rexford Tugwell, Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Arthur Miller, Dashiell Hammett, Hellen Keller, Thomas Mann, Aaron Copland, Claude Pepper, Eugene O'Neill, Glen H. Taylor, John Abt, Edna Ferber, Thornton Wilder, Carl Van Doren, Fredric March and Gene Kelly.

Davidson supported Henry A. Wallace in the 1948 Presidential Election. Wallace's running-mate was Glen H. Taylor, the left-wing senator for Idaho. A group of conservatives, including Henry Luce, Clare Booth Luce, Adolf Berle, Lawrence Spivak and Hans von Kaltenborn, sent a cable to Ernest Bevin, the British foreign secretary, that the PCA were only "a small minority of Communists, fellow-travelers and what we call here totalitarian liberals." Winston Churchill agreed and described Wallace and his followers as "crypto-Communists".

During his lifetime Davidson produced busts of Arthur Conan Doyle, Clarence Darrow, Charlie Chaplin, Lincoln Steffens, Israel Zangwill, Albert Einstein, Emma Goldman, Frank Harris, Hellen Keller, John D. Rockefeller, Dolores Ibárruri, Franklin Roosevelt, Henry A. Wallace, Walt Whitman, W. Averell Harriman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, H. G. Wells, Gertrude Stein, Josip Tito, Carl Sandburg, Edward Willis Scripps, George Bernard Shaw, Mahatma Gandhi, James Joyce, Rudyard Kipling, Robert M. La Follette, D. H. Lawrence, Henry Luce, Andrew Mellon, James Barrie, Joseph Conrad, Charles G. Dawes, Will Rogers, Anatole France, André Gide, Robinson Jeffers, John Marin and Ida Rubinstein.

Jo Davidson died on 2nd January, 1952.

On this day in 1909, Dora Marsden, Rona Robinson and Mary Gawthorpe decided to take part in another protest. According to Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990): "Dressed in University gowns they entered the meeting and just before Morley began, raised the question of the recent forced feeding of women in Winson Green. There was an uproar, and the three were quickly bundled out and arrested on the pavement." This time they were released without charge.

On this day in 1912 Sarah Carwin was charged with breaking seven windows at 179-183, Regent Street. This included at the jeweller's J. C. Vickery. One of his shop assistants, caught Carwin. In court he said she appealed to a bystander for protection. Carwin said that needed help because the man was acting like a "raging bull". Along with Ada Wright, Olive Wharry and Kitty Marion she was sentenced to six months in Winston Green Prison. Carwin went on hunger-strike and after being forced-fed the "deterioration in her physical condition led to her release". Her biographer, Francis Marbella Unwin, claimed that "she resisted with her utmost strength" and this left her "permanently injured".

Sarah Carwin, the daughter of John Carwin (1835-1888) and Jerusha Brown Carwin (1828-1866), was born in Bolton on 16th August 1863. At the time John Carwin was a "Cotton Carder" working in Rochdale.

In 1866 the family moved to Russia where it is believed that John Carwin attempted to start up a business in the textile industry. They returned to England in 1873. At the age of 18 she became a nursery governess in St Petersburg.

After her return in 1885 she joined the Methodist Sisterhood of the West London Mission. As Diane Atkinson has pointed out: "Many of the young women Sarah Carwin worked with were seasonal workers in the garment trade who were sacked when the fashion was over. By 1891 Sarah aged twenty-eight, had started a co-operative dressmaking business in Marylebone to provide such women with regular employment and a steady income."

Carwin enrolled as a trainee nurse at Great Ormond Street children's hospital, and qualified in 1896 and the following year joined with a friend in "a similar, larger, undertaking" . In 1901 she ran a home for a dozen illegitimate babies in Caterham. This was followed by becoming the nurse in charge of the Invalid Children's Special School founded by Mary Humphry Ward at the Passmore Edwards Settlement.

It is believed that Carwin became a feminist and anti-imperialist after reading the work of Olive Schreiner. Carwin joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and in February 1909 was arrested along with Mary Allen, Constance Lytton, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Caroline Watts for taking part in a demonstration outside the House of Commons.

On 29th June, 1909, Sarah Carwin and Ada Wright were arrested for breaking government windows. They were sentenced to a month in prison. While in Holloway they broke every window in their cells as a protest. When they were called before the Prison Board, faced with twenty seated men, Carwin went on the attack: "Give me a chair, why should we stand when all these men are sitting down?" (6) Both women were released after being on hunger strike for six days.

Sarah Carwin was imprisoned several times for window-breaking. Described as a "tall, interesting-looking woman" Emmeline Pankhurst wrote to her that: "Women have reason to be grateful that you and others have the courage to play the soldier's part in the war we are waging in the political freedom of women."

In May 1914 she was in trouble again: "Following on the suffragist disturbances at Bow Street Police Court on Friday, five defendants appeared before Sir John Dickinson on Saturday. There was an attempt to make another scene, but this succeeded only in part. One of the defendants, Sarah Carwin, kept up a running comment of "That's a lie" during the police evidence, and she told the Magistrate that she had the utmost contempt for anything that happened in that Court. She was ordered to be bound over, and left the dock protesting against this course."

On the outbreak of the First World War Carwin left the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She lived in the country for many years with a woman friend to whom she was "devotedly attached". When her friend died she lived in France and Italy. Francis Marbella Unwin pointed out: "She spared herself nothing in the pursuit of her ideals... a few weeks before her death she said that if she could choose any part of her life to live over again she would choose the part she had devoted to the suffrage. It had seemed the most worthwhile."

Sarah Carwin died in Elham, Kent, on 30th December 1933.

On this day in 1913 Richard Helms was born in St Davids, Philadelphia. After graduating from Williams College, Massachusetts, he joined the United Press news agency and in 1936 was sent to Nazi Germany to cover the Berlin Olympic Games. On his return to the United States he joined the advertising department of the Indianapolis Times. Two years later he became national advertising manager.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor Helms joined the United States Navy. In August, 1943, he was transferred to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) that had made established by William Donovan. The OSS had responsibility for collecting and analyzing information about countries at war with the United States. It also helped to organize guerrilla fighting, sabotage and espionage.

After the surrender of Germany in 1945, Helms helped interview suspected Nazi war criminals. Helms remained in the OSS and in 1946 was put in charge of intelligence and counter-intelligence activities in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. The following year Helms joined the recently formed Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). His first task was to mount a mount a massive convert campaign against the Communist Party during the Italian General Election. This was highly successful and this encouraged President Harry S. Truman to establish the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), an organization instructed to conduct covert anti-Communist operations around the world. In August, 1952, OPC and the Office of Special Operations (the espionage division) were merged to form the Directorate of Plans (DPP).

Frank Wisner was appointed head of the DPP and he appointed Helms as his chief of operations. In December, 1956, Wisner suffered a mental breakdown and was diagnosed as suffering from manic depression. During his absence Wisner's job was covered by Helms. The CIA sent Wisner to the Sheppard-Pratt Institute, a psychiatric hospital near Baltimore. He was prescribed psychoanalysis and shock therapy (electroconvulsive treatment). It was not successful and still suffering from depression, he was released from hospital in 1958.

Wisner was too ill to return to his post as head of the DDP. Allen W. Dulles therefore sent him to London to be CIA chief of station in England. Dulles decided that Richard Bissell rather than Helms should become the new head of the DPP. Helms was named as his deputy. Together they became responsible for what became known as the CIA's Black Operations. This involved a policy that was later to become known as Executive Action (a plan to remove unfriendly foreign leaders from power). This including a coup d'état that overthrew the Guatemalan government of Jacobo Arbenz in 1954 after he introduced land reforms and nationalized the United Fruit Company.

Other political leaders deposed by Executive Action included Patrice Lumumba of the Congo, the Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo, General Abd al-Karim Kassem of Iraq and Ngo Dinh Diem, the leader of South Vietnam. However, his main target was Fidel Castro who had established a socialist government in Cuba.

In March I960, President Dwight Eisenhower of the United States approved a CIA plan to overthrow Castro. The plan involved a budget of $13 million to train "a paramilitary force outside Cuba for guerrilla action." The strategy was organised by Bissell and Helms. An estimated 400 CIA officers were employed full-time to carry out what became known as Operation Mongoose.

Sidney Gottlieb of the CIA Technical Services Division was asked to come up with proposals that would undermine Castro's popularity with the Cuban people. Plans included a scheme to spray a television studio in which he was about to appear with an hallucinogenic drug and contaminating his shoes with thallium which they believed would cause the hair in his beard to fall out.

These schemes were rejected and instead Bissell and Helms decided to arrange the assassination of Fidel Castro. In September 1960, Bissell and Allen W. Dulles, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), initiated talks with two leading figures of the Mafia, Johnny Roselli and Sam Giancana. Later, other crime bosses such as Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante and Meyer Lansky became involved in this plot against Castro.

Robert Maheu, a veteran of CIA counter-espionage activities, was instructed to offer the Mafia $150,000 to kill Fidel Castro. The advantage of employing the Mafia for this work is that it provided CIA with a credible cover story. The Mafia were known to be angry with Castro for closing down their profitable brothels and casinos in Cuba. If the assassins were killed or captured the media would accept that the Mafia were working on their own.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation had to be brought into this plan as part of the deal involved protection against investigations against the Mafia in the United States. Castro was later to complain that there were twenty ClA-sponsered attempts on his life. Eventually Johnny Roselli and his friends became convinced that the Cuban revolution could not be reversed by simply removing its leader. However, they continued to play along with this CIA plot in order to prevent them being prosecuted for criminal offences committed in the United States.

When John F. Kennedy replaced Dwight Eisenhower as president of the United States he was told about the CIA plan to invade Cuba. Kennedy had doubts about the venture but he was afraid he would be seen as soft on communism if he refused permission for it to go ahead. Kennedy's advisers convinced him that Fidel Castro was an unpopular leader and that once the invasion started the Cuban people would support the ClA-trained forces.

On April 14, 1961, B-26 planes began bombing Cuba's airfields. After the raids Cuba was left with only eight planes and seven pilots. Two days later five merchant ships carrying 1,400 Cuban exiles arrived at the Bay of Pigs. The attack was a total failure. Two of the ships were sunk, including the ship that was carrying most of the supplies. Two of the planes that were attempting to give air-cover were also shot down. Within seventy-two hours all the invading troops had been killed, wounded or had surrendered.

After the CIA's internal inquiry into this fiasco, Allen W. Dulles was sacked by President John F. Kennedy and Richard Bissell was forced to resign. Helms now took over the Directorate for Plans. His deputy was Thomas H. Karamessines. Helms now introduced a campaign that involved covert attacks on the Cuban economy.

In 1962 Richard Helms became increasingly involved in the Vietnam War. By this time President John F. Kennedy was convinced that Ngo Dinh Diem would never be able to unite the South Vietnamese against communism. Several attempts had already been made to overthrow Diem but Kennedy had always instructed the CIA and the US military forces in Vietnam to protect him. Eventually, in order to obtain a more popular leader of South Vietnam, Kennedy agreed that the role of the CIA should change. Lucien Conein, a CIA operative, provided a group of South Vietnamese generals with $40,000 to carry out the coup with the promise that US forces would make no attempt to protect Diem. At the beginning of November, 1963, President Diem was overthrown by a military coup. The generals had promised Diem that he would be allowed to leave the country they changed their mind and killed him.

When John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Helms was given the responsibility of investigating Lee Harvey Oswald and the CIA. Helms initially appointed John M. Whitten to undertake the agency's in-house investigation. After talking to Winston Scott, the CIA station chief in Mexico City, Whitten discovered that Oswald had been photographed at the Cuban consulate in early October, 1963. Nor had Scott told Whitten, his boss, that Oswald had also visited the Soviet Embassy in Mexico. In fact, Whitten had not been informed of the existence of Oswald, even though there was a 201 pre-assassination file on him that had been maintained by the Counterintelligence/Special Investigative Group.

John M. Whitten and his staff of 30 officers, were sent a large amount of information from the FBI. According to Gerald D. McKnight "the FBI deluged his branch with thousands of reports containing bits and fragments of witness testimony that required laborious and time-consuming name checks." Whitten later described most of this FBI material as "weirdo stuff". As a result of this initial investigation, Whitten told Richard Helms that he believed that Oswald had acted alone in the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

On 6th December, Nicholas Katzenbach invited John M. Whitten and Birch O'Neal, Angleton's trusted deputy and senior Special Investigative Group (SIG) officer to read Commission Document 1 (CD1), the report that the FBI had written on Lee Harvey Oswald. Whitten now realized that the FBI had been withholding important information on Oswald from him. He also discovered that Richard Helms had not been providing him all of the agency's available files on Oswald. This included Oswald's political activities in the months preceding the assassination.

Whitten had a meeting where he argued that Oswald's pro-Castro political activities needed closer examination, especially his attempt to shoot the right-wing General Edwin Walker, his relationship with anti-Castro exiles in New Orleans, and his public support for the pro-Castro Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Whitten added that has he had been denied this information, his initial conclusions on the assassination were "completely irrelevant."

Helms responded by taking Whitten off the case. James Jesus Angleton, chief of the CIA's Counterintelligence Branch, was now put in charge of the investigation. According to Gerald McKnight (Breach of Trust) Angleton "wrested the CIA's in-house investigation away from John Whitten because he either was convinced or pretended to believe that the purpose of Oswald's trip to Mexico City had been to meet with his KGB handlers to finalize plans to assassinate Kennedy."

President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Admiral William Raborn, head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Helms became Raborn's deputy but became increasingly influential over decisions being made in Vietnam. This included the covert action in neighbouring Laos and the formation of South Vietnamese counter-terror teams.

The following year Johnson promoted Helms to become head of the CIA. He was the first director of the organization to have worked his way up from the ranks. His standing with Johnson improved when he successfully predicted a quick victory for Israel during the Six Day War in June, 1967. However, Helms information about the size of enemy forces in Vietnam was less accurate. Johnson was told in November, 1967, that the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces had fallen to 248,000. In reality the true figure was close to 500,000 and United States troops were totally unprepared for the Tet Offensive.

Under President Richard Nixon, Helms agreed to implement what became known as the Huston Plan. This was a proposal for all the country's security services to combine in a massive internal surveillance operation. In doing so, Helms became involved in a secret conspiracy as it was illegal for the Central Intelligence Agency to operate within the United States.

In 1970 it seemed that Salvador Allende and his Socialist Workers' Party would win the general election in Chile. Various multinational companies, including International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT), feared what would happen if Allende gained control of the country. Helms agreed to use funds supplied by these companies to help the right-wing party gain power. When this strategy ended in failure, Nixon ordered Helms to help the Chilean armed forces to overthrow Allende. On 11th September, 1973, a military coup removed Allende's government from power. Allende died in the fighting in the presidential palace in Santiago and General Augusto Pinochet replaced him as president.

During the Watergate Scandal President Richard Nixon became concerned about the activities of the Central Intelligence Agency. Three of those involved in the burglary, E. Howard Hunt, Eugenio Martinez and James W. McCord had close links with the CIA. Nixon and his aides attempted to force the CIA director, Richard Helms, and his deputy, Vernon Walters, to pay hush-money to Hunt, who was attempting to blackmail the government. Although it seemed Walters was willing to do this, Helms refused. In February, 1973, Nixon sacked Helms. His deputy, Thomas H. Karamessines, resigned in protest. The following month Helms became U.S. Ambassador to Iran.

James Schlesinger now became the new director of the CIA. Schlesinger was heard to say: “The clandestine service was Helms’s Praetorian Guard. It had too much influence in the Agency and was too powerful within the government. I am going to cut it down to size.” This he did and over the next three months over 7 per cent of CIA officers lost their jobs.

On 9th May, 1973, James Schlesinger issued a directive to all CIA employees: “I have ordered all senior operating officials of this Agency to report to me immediately on any activities now going on, or might have gone on in the past, which might be considered to be outside the legislative charter of this Agency. I hereby direct every person presently employed by CIA to report to me on any such activities of which he has knowledge. I invite all ex-employees to do the same. Anyone who has such information should call my secretary and say that he wishes to talk to me about “activities outside the CIA’s charter”.

There were several employees who had been trying to complain about the illegal CIA activities for some time. As Cord Meyer pointed out, this directive “was a hunting license for the resentful subordinate to dig back into the records of the past in order to come up with evidence that might destroy the career of a superior whom he long hated.”

In 1975 the Senate Foreign Relations Committee began investigating the CIA. Senator Stuart Symington asked Richard Helms if the agency had been involved in the removal of Salvador Allende. Helms replied no. He also insisted that he had not passed money to opponents of Allende.

Investigations by the CIA's Inspector General and by Frank Church and his Select Committee on Intelligence Activities showed that Helms had lied to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. They also discovered that Helms had been involved in illegal domestic surveillance and the murders of Patrice Lumumba, General Abd al-Karim Kassem and Ngo Dinh Diem. Helms was eventually found guilty of lying to Congress and received a suspended two-year prison sentence.

In its final report, issued in April 1976, the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities concluded: “Domestic intelligence activity has threatened and undermined the Constitutional rights of Americans to free speech, association and privacy. It has done so primarily because the Constitutional system for checking abuse of power has not been applied.” The committee also revealed details for the first time of what the CIA called Operation Mockingbird.

The committee also reported that the Central Intelligence Agency had withheld from the Warren Commission, during its investigation of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, information about plots by the Government of the United States against Fidel Castro of Cuba; and that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had conducted a counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO) against Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

On 16th May, 1978, John M. Whitten appeared before the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA). He criticised Richard Helms for not making a full disclosure about the Rolando Cubela plot to the Warren Commission. He added " I think that was a morally highly reprehensible act, which he cannot possibly justify under his oath of office or any other standard of professional service."

Whitten also said that if he had been allowed to continue with the investigation he would have sought out what was going on at JM/WAVE. This would have involved the questioning of Ted Shackley, David Sanchez Morales, Carl E. Jenkins, Rip Robertson, George Joannides, Gordon Campbell and Thomas G. Clines. As Jefferson Morley has pointed out in The Good Spy: "Had Whitten been permitted to follow these leads to their logical conclusions, and had that information been included in the Warren Commission report, that report would have enjoyed more credibility with the public. Instead, Whitten's secret testimony strengthened the HSCA's scathing critique of the C.I.A.'s half-hearted investigation of Oswald. The HSCA concluded that Kennedy had been killed by Oswald and unidentifiable co-conspirators."

John M. Whitten also told the HSCA that James Jesus Angleton involvement in the investigation of the assassination of John F. Kennedy was "improper". Although he was placed in charge of the investigation by Richard Helms, Angleton "immediately went into action to do all the investigating". When Whitten complained to Helms about this he refused to act.

Whitten believes that Angleton's attempts to sabotage the investigation was linked to his relationship with the Mafia. Whitten claims that Angleton also prevented a CIA plan to trace mob money to numbered accounts in Panama. Angleton told Whitten that this investigation should be left to the FBI. When Whitten mentioned this to a senior CIA official, he replied: "Well, that's Angleton's excuse. The real reason is that Angleton himself has ties to the Mafia and he would not want to double-cross them."

Whitten also pointed out that as soon as Angleton took control of the investigation he concluded that Cuba was unimportant and focused his internal investigation on Oswald's life in the Soviet Union. If Whitten had remained in charge he would have "concentrated his attention on CIA's JM/WAVE station in Miami, Florida, to uncover what George Joannides, the station chief, and operatives from the SIG and SAS knew about Oswald."

When he appeared before the HSCA Whitten revealed that he had been unaware of the CIA's Executive Action program. He added that he thought it possible that Lee Harvey Oswald might have been involved in this assassination operation.

Richard Helms died on 22nd October, 2002. As one commentator pointed out at the time: "Helms had gone to his grave with the sole knowledge of what Congress did not manage to uncover." His autobiography, A Look Over My Shoulder: A Life in the CIA, was published in 2003.

On this day in 1919 McGeorge Bundy was born in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from Yale University in 1940 he joined the office of Facts and Figures in Washington. After the Second World War he took up a teaching appointment at Harvard University. Eventually he became Dean of Arts and Sciences (1953-61).

When John F. Kennedy was elected he appointed Bundy as his National Security Adviser. William Attwood was the leading advocate inside the Kennedy Administration for talking to Fidel Castro about the potential for improving relations. He was supported by Bundy who suggested to Kennedy that there should be a "gradual development of some form of accommodation with Castro".

In April 1963 Lisa Howard arrived in Cuba to make a documentary on the country. In an interview with Howard, Fidel Castro agreed that a rapprochement with Washington was desirable. On her return Howard met with the Central Intelligence Agency. Deputy Director Richard Helms reported to John F. Kennedy on Howard's view that "Fidel Castro is looking for a way to reach a rapprochement with the United States." After detailing her observations about Castro's political power, disagreements with his colleagues and Soviet troops in Cuba, the memo concluded that "Howard definitely wants to impress the U.S. Government with two facts: Castro is ready to discuss rapprochement and she herself is ready to discuss it with him if asked to do so by the US Government."

CIA Director John McCone was strongly opposed to Lisa Howard being involved with these negotiations with Castro. He argued that it might "leak and compromise a number of CIA operations against Castro". In a memorandum to McGeorge Bundy, McCone commented that the "Lisa Howard report be handled in the most limited and sensitive manner," and "that no active steps be taken on the rapprochement matter at this time."

Arthur Schlesinger explained to Anthony Summers in 1978 why the CIA did not want John F. Kennedy to negotiate with Fidel Castro during the summer of 1963: "The CIA was reviving the assassination plots at the very time President Kennedy was considering the possibility of normalization of relations with Cuba - an extraordinary action. If it was not total incompetence - which in the case of the CIA cannot be excluded - it was a studied attempt to subvert national policy."

Lisa Howard now decided to bypass the CIA and in May, 1963, published an article in the journal, War and Peace Report, Howard wrote that in eight hours of private conversations Castro had shown that he had a strong desire for negotiations with the United States: "In our conversations he made it quite clear that he was ready to discuss: the Soviet personnel and military hardware on Cuban soil; compensation for expropriated American lands and investments; the question of Cuba as a base for Communist subversion throughout the Hemisphere." Howard went on to urge the Kennedy administration to "send an American government official on a quiet mission to Havana to hear what Castro has to say." A country as powerful as the United States, she concluded, "has nothing to lose at a bargaining table with Fidel Castro."

William Attwood read Howard's article and on 12th September, 1963, he had a long conversation with her on the phone. This apparently set in motion a plan to initiate secret talks between the United States and Cuba. Six days later Attwood sent a memorandum to Under Secretary of State Averell Harriman and U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson. Attwood asked for permission to establish discreet, indirect contact with Fidel Castro.

On September 20, John F. Kennedy gave permission to authorize Attwood's direct contacts with Carlos Lechuga, the Cuban ambassador to the United Nations. According to Attwood: "I then told Miss Howard to set up the contact, that is to have a small reception at her house so that it could be done very casually, not as a formal approach by us." Howard met Lechuga at the UN on 23rd September 23. Howard invited Lechuga to come to a party at her Park Avenue apartment that night to meet Attwood.

The next day William Attwood met with Robert Kennedy in Washington and reported on the talks with Lechuga. According to Attwood the attorney general believed that a trip to Cuba would be "rather risky." It was "bound to leak and... might result in some kind of Congressional investigation." Nevertheless, he thought the matter was "worth pursuing."

On 5th November 5, McGeorge Bundy recorded that "the President was more in favor of pushing towards an opening toward Cuba than was the State Department, the idea being - well, getting them out of the Soviet fold and perhaps wiping out the Bay of Pigs and maybe getting back into normal." Bundy designated his assistant, Gordon Chase, to be Attwood's direct contact at the White House.

Attwood continued to use Lisa Howard as his contact with Fidel Castro. In October 1963, Castro told Howard that he was very keen to open negotiations with Kennedy. Castro even offered to send a plane to Mexico to pick up Kennedy's representative and fly him to a private airport near Veradero where Castro would talk to him alone.