Lisa Howard

Lisa Howard was born on 24th April, 1930. She became an actress and in 1950 played the role of a Soviet official in the anti-communist film, Guilty of Treason. She also appeared in Mr. & Mrs. North (1952), Donovan's Brain (1953) and Sabaka (1954). In the late 1950s she was a regular on CBS's Edge of Night.

In 1960 Howard became a correspondent for Mutual Radio Network. Covering the United Nations, she became the first journalist to secure an interview with Nikita Khrushchev. In June 1961 she covered the Vienna summit between President John F. Kennedy and the Soviet leader. Later that year she became the anchor for ABC's noontime news broadcast, The News Hour with Lisa Howard.

In April 1963 McGeorge Bundy suggested to President John F. Kennedy that there should be a "gradual development of some form of accommodation with Castro". In an interview given in 1995, Bundy, said Kennedy needed "a target of opportunity" to talk to Fidel Castro.

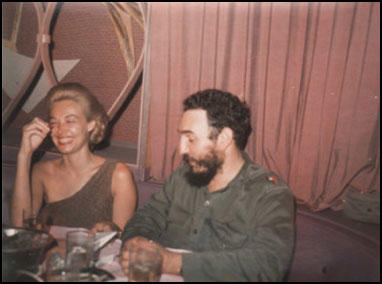

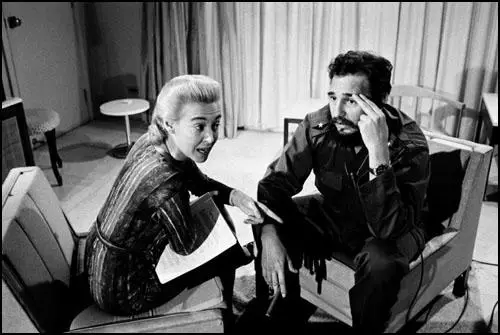

In April 1963 Howard arrived in Cuba to make a documentary on the country. In an interview with Howard, Castro agreed that a rapprochement with Washington was desirable. On her return Howard met with the Central Intelligence Agency. Deputy Director Richard Helms reported to John F. Kennedy on Howard's view that "Fidel Castro is looking for a way to reach a rapprochement with the United States." After detailing her observations about Castro's political power, disagreements with his colleagues and Soviet troops in Cuba, the memo concluded that "Howard definitely wants to impress the U.S. Government with two facts: Castro is ready to discuss rapprochement and she herself is ready to discuss it with him if asked to do so by the US Government."

CIA Director John McCone was strongly opposed to Howard being involved with these negotiations with Castro. He argued that it might "leak and compromise a number of CIA operations against Castro". In a memorandum to McGeorge Bundy, McCone commented that the "Lisa Howard report be handled in the most limited and sensitive manner," and "that no active steps be taken on the rapprochement matter at this time."

Arthur Schlesinger explained to Anthony Summers in 1978 why the CIA did not want President Kennedy to negotiate with Fidel Castro during the summer of 1963: "The CIA was reviving the assassination plots at the very time President Kennedy was considering the possibility of normalization of relations with Cuba - an extraordinary action. If it was not total incompetence - which in the case of the CIA cannot be excluded - it was a studied attempt to subvert national policy."

Howard now decided to bypass the CIA and in May, 1963, published an article in the journal, War and Peace Report, Howard wrote that in eight hours of private conversations Castro had shown that he had a strong desire for negotiations with the United States: "In our conversations he made it quite clear that he was ready to discuss: the Soviet personnel and military hardware on Cuban soil; compensation for expropriated American lands and investments; the question of Cuba as a base for Communist subversion throughout the Hemisphere." Howard went on to urge the Kennedy administration to "send an American government official on a quiet mission to Havana to hear what Castro has to say." A country as powerful as the United States, she concluded, "has nothing to lose at a bargaining table with Fidel Castro."

William Attwood, an adviser to the US mission to the United Nations, read Howard's article and on 12th September, 1963, he had a long conversation with her on the phone. This apparently set in motion a plan to initiate secret talks between the United States and Cuba. Six days later Attwood sent a memorandum to Under Secretary of State Averell Harriman and U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson. Attwood asked for permission to establish discreet, indirect contact with Fidel Castro.

On September 20, John F. Kennedy gave permission to authorize Attwood's direct contacts with Carlos Lechuga, the Cuban ambassador to the United Nations. According to Attwood: "I then told Miss Howard to set up the contact, that is to have a small reception at her house so that it could be done very casually, not as a formal approach by us." Howard met Lechuga at the UN on 23rd September 23. Howard invited Lechuga to come to a party at her Park Avenue apartment that night to meet Attwood.

The next day Attwood met with Robert Kennedy in Washington and reported on the talks with Lechuga. According to Attwood the attorney general believed that a trip to Cuba would be "rather risky." It was "bound to leak and... might result in some kind of Congressional investigation." Nevertheless, he thought the matter was "worth pursuing."

On 5th November 5, McGeorge Bundy recorded that "the President was more in favor of pushing towards an opening toward Cuba than was the State Department, the idea being - well, getting them out of the Soviet fold and perhaps wiping out the Bay of Pigs and maybe getting back into normal." Bundy designated his assistant, Gordon Chase, to be Attwood's direct contact at the White House.

Attwood continued to use Howard as his contact with Fidel Castro. In October 1963, Castro told Howard that he was very keen to open negotiations with Kennedy. Castro even offered to send a plane to Mexico to pick up Kennedy's representative and fly him to a private airport near Veradero where Castro would talk to him alone.

John F. Kennedy now decided to send Attwood to meet Castro. On 14th November, 1963, Lisa Howard conveyed this message to her Cuban contact. In an attempt to show his good will, Kennedy sent a coded message to Castro in a speech delivered on 19th November. The speech included the following passage: "Cuba had become a weapon in an effort dictated by external powers to subvert the other American republics. This and this alone divides us. As long as this is true, nothing is possible. Without it, everything is possible."

Kennedy also sent a message to Fidel Castro via the French journalist Jean Daniel. According to Daniel: "Kennedy expressed some empathy for Castro's anti-Americanism, acknowledging that the United States had committed a number of sins in pre-revolutionary Cuba." Kennedy told Daniel that the trade embargo against Cuba could be lifted if Castro ended his support for left-wing movements in the Americas.

Daniel delivered this message on 19th November. Castro told Daniel that Kennedy could become "the greatest president of the United States, the leader who may at last understand that there can be coexistence between capitalists and socialists, even in the Americas." Daniel was with Castro when news arrived that Kennedy had been assassinated Castro turned to Daniel and said:"This is an end to your mission of peace. Everything is changed."

President Lyndon B. Johnson was told about these negotiations in December, 1963. He refused to continue these talks and claimed that the reason for this was that he feared that Richard Nixon, the expected Republican candidate for the presidency, would accuse him of being soft on communism.

Howard refused to give up and in 1964 she resumed talks with Fidel Castro. On 12th February, 1964, she sent a message to President Johnson from Castro asking for negotiations to be restarted. When Johnson did not respond to this message she contacted Adlai Stevenson at the United Nations. On 26th June 26, Stevenson sent a memo to Johnson saying that he felt that "all of our crises could be avoided if there was some way to communicate; that for want of anything better, he assumed that he could call (Lisa Howard) and she call me and I would advise you." In a memorandum marked top secret, Gordon Chase wrote that it was important "to remove Lisa from direct participation in the business of passing messages" from Cuba.

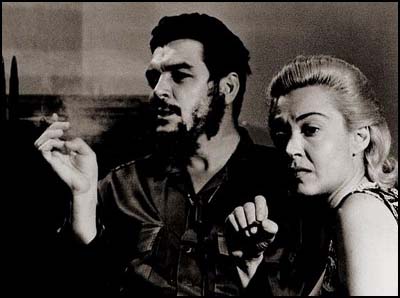

In December, 1964, Howard met with Che Guevara to the United Nations. Details of this meeting was sent to McGeorge Bundy. When Howard got no response she arranged for Eugene McCarthy to meet with Guevara in her apartment on 16th December.

This created panic in the White House and the following day Under Secretary George Ball told Eugene McCarthy that the meeting must remain a secret because there was "suspicion throughout Latin America that the U.S. might make a deal with Cuba behind the backs of the other American states."

Howard continued to try and obtain a negotiated agreement between Fidel Castro and Lyndon B. Johnson. As a result she was fired by ABC because she had "chosen to participate publicly in partisan political activity contrary to long established ABC news policy."

Lisa Howard died at East Hampton, Long Island, on 4th July, 1965. It was officially reported that she had committed suicide. Apparently, she had taken one hundred phenobarbitols. It was claimed she was depressed as a result of losing her job and suffering a miscarriage.

YouTube Video

Fidel Castro's interview with Lisa Howard

Primary Sources

(1) National Security Archive (24th November, 2003)

On the 40th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and the eve of the broadcast of a new documentary film on Kennedy and Castro, the National Security Archive today posted an audio tape of the President and his national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy, discussing the possibility of a secret meeting in Havana with Castro. The tape, dated only seventeen days before Kennedy was shot in Dallas, records a briefing from Bundy on Castro's invitation to a US official at the United Nations, William Attwood, to come to Havana for secret talks on improving relations with Washington. The tape captures President Kennedy's approval if official US involvement could be plausibly denied.

The possibility of a meeting in Havana evolved from a shift in the President's thinking on the possibility of what declassified White House records called "an accommodation with Castro" in the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Proposals from Bundy's office in the spring of 1963 called for pursuing "the sweet approach…enticing Castro over to us," as a potentially more successful policy than CIA covert efforts to overthrow his regime. Top Secret White House memos record Kennedy's position that "we should start thinking along more flexible lines" and that "the president, himself, is very interested in (the prospect for negotiations)." Castro, too, appeared interested. In a May 1963 ABC News special on Cuba, Castro told correspondent Lisa Howard that he considered a rapprochement with Washington "possible if the United States government wishes it. In that case," he said, "we would be agreed to seek and find a basis" for improved relations.

(2) Verbal message given by Lisa Howard on February 12, 1964 in Havana, Cuba. Howard was unable to deliver the message directly to President Lyndon B. Johnson and eventually she gives it to Adlai Stevenson at the United Nations. The document was eventually declassified on July 12, 1995

1. Please tell President Johnson that I earnestly desire his election to the Presidency in November… though that appears assured. But if there is anything I can do to add to his majority (aside from retiring from politics), I shall be happy to cooperate. Seriously, I observe how the Republicans use Cuba as a weapon against the Democrats. So tell President Johnson to let me know what I can do, if anything. Naturally, I know that my offer of assistance would be of immense value to the Republicans - so this would remain our secret. But if the President wishes to pass word to me he can do so through you (Lisa Howard). He must know that he can trust you; and I know that I can trust you to relay a message accurately.

2. If the President feels it necessary during the campaign to make bellicose statements about Cuba or even to take some hostile action - if he will inform me, unofficially, that a specific action is required because of domestic political considerations, I shall understand and not take any serious retaliatory action.

3. Tell the President that I understand quite well how much political courage it took for President Kennedy to instruct you (Lisa Howard) and Ambassador Attwood to phone my aide in Havana for the purpose of commencing a dialogue toward a settlement of our differences. Ambassador Attwood suggested that I prepare an agenda for such talks and send the agenda to my U.N. Ambassador. That was on November 18th. The agenda was being prepared when word arrived that President Kennedy was assassinated. I hope that we can soon continue where Ambassador Attwood's phone conversation to Havana left off… though I'm aware that pre-electoral political considerations may delay this approach until after November.

4. Tell the President (and I cannot stress this too strongly) that I seriously hope that Cuba and the United states can eventually respect and negotiate our differences. I believe that there are no areas of contention between us that cannot be discussed and settled within a climate of mutual understanding. But first, of course, it is necessary to discuss our differences. I now believe that this hostility between Cuba and the United States is both unnatural and unnecessary - and it can be eliminated.

5. Tell the President he should not interpret my conciliatory attitude, my desire for discussions as a sign of weakness. Such an interpretation would be a serious miscalculation. We are not weak… the Revolution is strong… very strong. Nothing, absolutely nothing that the Untied States can do will destroy the Revolution. Yes, we are strong. And it is from this position of strength that we wish to resolve our differences with the United States and to live in peace with all the nations of the world.

6. Tell the president I realize fully the need for absolute secrecy, if he should decide to continue the Kennedy approach. I revealed nothing at that time… I have revealed nothing since… I would reveal nothing now.

(3) William Attwood, secret memorandum to Averell Harriman and Adlai Stevenson (18th September, 1963).

The impact of present US policy is mainly negative: (a) It aggravates Castro's anti-Americanism and his desire to cause us trouble and embarrassment. (b) In the eyes of a world largely made up of small countries, it freezes us in the unattractive posture of a big country trying to bully a small country... It would seem that we have something to gain and nothing to lose by finding out whether in fact Castro does want to talk and what concessions he would be prepared to make.

(4) William Attwood, memorandum (8th November, 1963)

Following is a chronology of events leading up to Castro’s invitation on October 31, to receive a U.S. official for talks in Cuba:

Soon after joining the U.S. Mission to the U.N. on August 26, I met Seydou Diallo, the Guinea Ambassador to Havana, whom I had known well in Conakray. [Attwood had been U.S. Ambassador to Guinea from March 1961 to May 1963].

He went out of his way to tell me that Castro was isolated from contact with neutralist diplomats by his “Communist entourage”….He, Diallo, had finally been able to see Castro alone once and was convinced he was personally receptive to changing courses and getting Cuba on the road to non-alignment….

In the first week of September, I also read ABC correspondent, Lisa Howard’s article, “Castro’s Overture,” [In War/Peace Report, September, 1963] based on her conversation with Castro last April. This article stressed Castro’s expressed desire for reaching an accommodation with the United States and a willingness to make substantial concessions to this end. On September 12, I talked with Miss Howard, whom I have known for some years, and she echoed Ambassador Diallo’s opinion that there was a rift between Castro and the Guevara-Hart-Alveida group on the question of Cuba’s future course.

On September 12, I discussed this with Under Secretary Harriman in Washington. He suggested I prepare a memo and we arranged to meet in New York the following week.

On September 18, I wrote a memorandum based on these talks and on corroborating information I had heard in Conakry…..

On September 23, I met Dr. Lechuga at Miss Howard’s apartment. She has been on good terms with Lechuga since her visit with Castro and invited him for a drink to met [sic] some friends who had also been to Cuba. I was just one of those friends. In the course of our conversation, which started with recollections of my own talks with Castro in 1959, I mentioned having read Miss Howard’s article. Lechuga hinted that Castro was indeed in a mood to talk. I told him that in my present position, I would need official authorization to make such a trip, and did not know if it would be forthcoming. However, I said an exchange of views might well be useful and that I would find out and let him know.

On September 24, I saw the Attorney-General in Washington, and gave him my September 18 memo, and reported my meeting with Lechuga. He said he would pass the memo on to Mr. McGeorge Bundy;…..

On September 27, I ran into Lechuga at the United Nations, where he was doing a television interview in the lobby with Miss Howard. I told him that I had discussed our talk in Washingon,….Meanwhile, he forewarned me that he would be making a ‘hard’ anti-U.S. speech in the United Nations on October 7.

On October 18, at dinner at the home of Mrs. Eugene Meyer, I talked with Mr. C.A. Doxiades, a noted Greek architect and town-planner, who had just returned from an architects congress in Havana, where he had talked alone to both Castro and Guevara, among others. He sought me out, as a government official, to say he was convinced Castro would welcome normalization of relations with the United States if he could do so without losing too much face….

On October 20, Miss Howard asked me if she might call Major Rene Vallejo, a Cuban surgeon who is also Castro’s current right-hand man and confidant. She said Vallejo helped her see Castro and made it plain to her he opposed the Guevara group. They became friends and talked on the phone several times since the interview….

On October 21, Gordon Chase called me from the White House in connection with my September 18 memo. I brought him up to date and said the ball was in his court.

On October 28, I ran into Lechuga in the U.N. Delegates Lounge….I said it was up to him and he could call me if he felt like it. He wrote down my extension.

On October 29, Vallejo again called Miss Howard at home…

On October 31, Vallejo called Miss Howard, apologizing for the delay and saying he had been out of town with Castro and “could not get to a phone from which I could call you.” He said Castro would very much like to talk to the U.S. official anytime and appreciated the importance of discretion to all concerned….

On November 1, Miss Howard reported the Vallejo call to me and I repeated it to Chase on November 4.

On November 5, I met with Bundy and Chase at the White House and informed them of the foregoing. The next day, Chase called and asked me to put it in writing.

(5) William Attwood, memorandum (22nd November, 1963)

If the CIA did find out what we were doing, this would have trickled down to the lower echelon of activists, and Cuban exiles, and the more gung-ho CIA people who had been involved since the Bay of Pigs. If word of a possible normalization of relations with Cuba leaked to these people, I can understand why they would have reacted so violently. This was the end of their dreams of returning to Cuba, and they might have been impelled to take violent action. Such as assassinating the President.

(6) Arthur Schlesinger gave an interview to Anthony Summers in 1978 that appeared in his book Conspiracy: Who Killed President Kennedy? (1980)

The CIA was reviving the assassination plots at the very time President Kennedy was considering the possibility of normalization of relations with Cuba - an extraordinary action. If it was not total incompetence - which in the case of the CIA cannot be excluded - it was a studied attempt to subvert national policy.... I think the CIA must have known about this initiative. They must certainly have realized that Bill Attwood and the Cuban representative to the U.N. were doing more than exchanging daiquiri recipes…They had all the wires tapped at the Cuban delegation to the United Nations….Undoubtedly if word leaked of President Kennedy’s efforts, that might have been exactly the kind of thing to trigger some explosion of fanatical violence. It seems to me a possibility not to be excluded.

(7) Dallas Morning News (5th July, 1965)

Lisa Howard, 35, former American Broadcasting Company news commentator, died Sunday, apparently of an overdose of sleeping tablets she had just purchased. Police described the death as an apparent suicide and quoted members of her family as saying she had been despondent since losing her unborn child a few weeks ago.

Police found her dazed in the parking lot of a pharmacy where she had purchased the pills. She died shortly after reaching a hospital.

Miss Howard and her husband, Walter Lowendahl, resided in Manhattan and had a summer home here. She was a strikingly attractive blonde.

She joined the ABC news stuff in 1961 and obtained several exclusive interviews with Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro.

ABC suspended her during the 1964 political campaign, when she was conducting her own program, "Lisa Howard and News with the Woman's Touch". She filed a 2 million-dollar suit against ABC, claiming she was fired for endorsing the election of President Johnson and supporting former Senator Kenneth B. Keating, Republican - New York.

Police said a prescription Miss Howard obtained Saturday for 10 sleeping tablets had been altered to 100 before she had it filled Sunday at the pharmacy.

Police received a call that a woman was acting strangely in the pharmacy's parking lot. Patrolman William Brockman said he found Miss Howard dazed, glassy-eyed and almost incoherent.

Brockman found no pills, but said the lot would be searched.

The officer took Miss Howard to the East Hampton Medical Center. "She kept mumbling something about a miscarriage," he said. "She collapsed before we got her inside." The patrolman said she was given oxygen and a tracheotomy was performed but she did not respond.

Brockman said Dr. Mary Johnson, assistant Suffolk medical examiner, tentatively ruled the death suicide and planned an autopsy.

(8) Peter Kornbluh, JFK & Castro: The Secret Quest For Accommodation (October 1999)

In February 1996, Robert Kennedy Jr. and his brother, Michael, traveled to Havana to meet with Fidel Castro. As a gesture of goodwill, they brought a file of formerly top secret US documents on the Kennedy administration's covert exploration of an accommodation with Cuba - a record of what might have been had not Lee Harvey Oswald, seemingly believing the president to be an implacable foe of Castro's Cuba, fired his fateful shots in Dallas. Castro thanked them for the file and shared his "impression that it was (President Kennedy's) intention after the missile crisis to change the framework" of relations between the United States and Cuba. "It's unfortunate," said Castro, that "things happened as they did, and he could not do what he wanted to do."

Would John F. Kennedy, had he lived, have been able to establish a modus vivendi with Fidel Castro? The question haunts almost 40 years of acrimonious U.S.-Cuba relations. In a Top Secret - Eyes Only memorandum written three days after the president's death, one of his White House aides, Gordon Chase, noted that "President Kennedy could have accommodated with Castro and gotten away with it with a minimum of domestic heat"--because of his track record "of being successfully nasty to Castro and the Communists" during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. Castro and his advisers believed the same. A CIA intelligence report, based on a high-level Cuban source and written for National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy in 1964, noted that "Fidel Castro felt that it was possible that President Kennedy would have gone on ultimately to negotiate with Cuba... (as an) acceptance of a fait accompli for practical reasons."

The file on the Kennedy administration's "Cuban contacts" that Robert Jr. and Michael took to Cuba (declassified at the request of the author) sheds significant light on a story that has never been fully told - John Kennedy's secret pursuit of a rapprochement with Fidel Castro. Along with papers recently released pursuant to the Kennedy Assassination Records Act of 1992, the documents reveal the escalating efforts toward negotiations in 1963 that, if successful, might have changed the ensuing decades of perpetual hostility between Washington and Havana. Given the continuing state of tension with Castro's regime, this history carries an immediate relevance for present policy makers. Indeed, with the Clinton administration buffeted between increasingly vocal critics of U.S. policy toward Cuba and powerful proponents of the status quo, reconstructing the hitherto secret record of Kennedy's efforts in the fall of 1963 to advance "the rapprochement track" with Castro is more relevant than ever.

John F. Kennedy would seem the most unlikely of presidents to seek an accommodation with Fidel Castro. His tragically abbreviated administration bore responsibility for some of the most infamous U.S. efforts to roll back the Cuban revolution: the Bay of Pigs invasion, the trade embargo, Operation Mongoose (a U.S. plan to destabilize the Castro government) and a series of CIA-Mafia assassination attempts against the Cuban leader. Castro's demise, Seymour M. Hersh argues in his book, The Dark Side of Camelot, "became a presidential obsession" until the end. "The top priority in the United States government - all else is secondary - no time, money, effort, or manpower is to be spared" is to find a "solution" to the Cuba problem, Attorney General Robert Kennedy told a high-level group of CIA and Pentagon officials in early 1962. The president's opinion, according to CIA minutes of the meeting, was that "the final chapter (on Cuba) has not been written."

Unbeknownst to all but his brother and a handful of advisers, however, in 1963 John Kennedy began pursuing an alternative script on Cuba: a secret dialogue toward an actual rapprochement with Castro. To a policy built upon "overt and covert nastiness," as Top Secret White House memoranda characterized U.S. operations against Cuba, was added "the sweet approach," meaning the possibility of "quietly enticing Castro over to us." National Security Council officials referred to this multitrack policy as "simil-opting"--the use of disparate methods toward the goal of moving Cuba out of the Soviet orbit...

Which country initiated the secret dialogue in the fall of 1963 remains a subject of historical dispute. The feelers toward a rapprochement "originally came, one might say, from their side," testified William Attwood, the key U.S. official involved in the subsequent talks, in a top secret deposition in 1975. In an interview, Cuba's former ambassador to the United Nations, Carlos Lechuga, insisted that "this was a Kennedy initiative, not Cuba's."

(9) Nan C. Druid, High Frontiers Magazine (1985)

A year later, Lisa Howard died under suspicious circumstances. Her death was attributed to suicide. Supposedly she took one hundred phenobarbitols at mid-day in a parking lot where she was found wandering in a daze. She had been fired because she had "chosen to participate publicly in partisan political activity contrary to long established established ABC news policy." Suspicions about her death"..... if ever substantiated.....would make her the second female news reporter (after Dorothy Kilgallen) whom assassination critics suspect was silenced because of her knowledge of the assassination."

Before her death, Lisa turned against Robert Kennedy, who was running for the U.S. Senate in New York. At a group meeting she organized with Gore Vidal in support of the incumbent Senator Keating, Bobby was described as " the very antithesis of his brother....ruthless, reactionary, and dangerously authoritarian." Explaining her reasons for forming the group she said, "if you feel strongly about something like this you can't remain silent. You have to show courage, and stand up and be counted." After ABC fired her she continued her "partisan political activity" remarking in a debate over Robert Kennedy that "Brothers are not necessarily the same....There was Cain and Abel." An interesting comparison.

In the wake of the Kennedy assassination there have been many more deaths than those of Mary Pinchot, Lisa Howard, and Dorothy Kilgallen. District Attorney Jim Garrison, of New Orleans, who investigated the Kennedy assassination said that "witnesses in this case do have a habit of dying at the most inconvenient times... a London insurance firm has prepared an acturial chart on the likelihood of 20 of the people involved in this case dying within 3 years of the assassination and found the odds 30 trillion to one.

There can be little doubt that the Kennedy assassination occurred because the young President's dream of peace. He had come to believe that his dream was possible and was killed because he took steps to bring it about.

(10) The Miami Herald (August, 1999)

It was March 1963, the height of the Cold War - a time of covert U.S. government assassination plots against Fidel Castro, Kennedy administration-sponsored exile raids and sabotage missions directed at Cuba.

It was also a time when Castro - still smarting from Moscow's failure to consult him about the withdrawal of missiles from the island in 1962 - was sending feelers to Washington about Cuba's interest in rapprochement.

President John F. Kennedy responded by overruling the State Department's position that Cuba break its ties with Soviet bloc nations as a precondition for talks on normal relations, according to an account to be published this week in the October issue of Cigar Aficionado magazine.

"The President himself is very interested in this one,'' says a March 1963 top-secret White House memo. ``The President does not agree that we should make the breaking of Sino-Soviet ties a non-negotiable point. We don't want to present Castro with a condition that he obviously cannot fulfill. We should start thinking along more flexible lines.''

The article, JFK and Castro: The Secret Quest for Accommodation, is based on recently declassified documents and written by Peter Kornbluh, a senior analyst at the Washington-based National Security Archive, a nongovernmental research institute. It traces the secret U.S.-Cuban contacts during the last months of the Kennedy administration and into the Johnson administration.

Although the general outlines of the contacts have been known, the account adds considerable detail, particularly the key role played by the late ABC correspondent Lisa Howard, who interviewed Castro in April 1963.

In addition to Howard, key players were McGeorge Bundy, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations' national security advisor, his assistant Gordon Chase and William Attwood, former Look magazine editor who at the time was an advisor to the U.S. mission at the United Nations.

On the Cuban side, the principal players were Carlos Lechuga, Cuba's U.N. ambassador, and Rene Vallejo, Castro's personal physician.

Initial overtures from Castro to Washington in late 1962 had been made through New York lawyer James Donovan, who had been enlisted by the Kennedy administration to negotiate the release of Bay of Pigs prisoners.

Efforts at normalization languished, however, until the involvement of Howard and Attwood started to bear fruit in the latter part of 1963.

In September, Attwood was authorized to have direct contacts with Lechuga, which were arranged by Howard at a Sept. 23 reception in her New York apartment. Attwood was to subsequently confer with Vallejo by telephone from Howard's apartment or she would relay messages between the two.

At one point, Vallejo conveyed a message to Attwood through Howard that said, "Castro would like to talk to the U.S. official anytime and appreciates the importance of discretion to all concerned. Castro would therefore be willing to send a plane to Mexico to pick up the official and fly him to a private airport near Varadero where Castro would talk to him alone. The plane would fly him back immediately.''

The invitation touched off a debate within the White House, with President Kennedy's position being that "it did not seem practicable'' to send an American official to Cuba "at this stage.''

Even so, the contacts continued to gain momentum until Kennedy's assassination on Nov. 22, 1963, when the "Attwood-Lechuga tie line'' was put on hold, with White House aides concerned that assassin Lee Harvey Oswald's reported pro-Castro sympathies would make an accommodation more difficult.

The back-channel contacts continued under President Lyndon Johnson through 1964, according to Kornbluh, but fizzled out in late 1964 as the fall presidential elections approached, despite ongoing efforts by Howard to keep them alive.

In December 1964, Howard made her final and unsuccessful effort by trying to arrange a meeting in New York between U.S. officials and Ernesto "Che'' Guevara, the Argentine-born Cuban revolutionary.

(11) Julian Borger, The Guardian (26th November, 2003)

A few days before his assassination, President Kennedy was planning a meeting with Cuban officials to negotiate the normalisation of relations with Fidel Castro, according to a newly declassified tape and White House documents.

The rapprochement was cut off in Dallas 40 years ago this week by Lee Harvey Oswald, who appears to have believed he was assassinating the president in the interests of the Cuban revolution.

But the new evidence suggests that Castro saw Kennedy's killing as a setback. He tried to restart a dialogue with the next administration, but Lyndon Johnson was at first too concerned about appearing soft on communism and later too distracted by Vietnam to respond.

A later attempt to restore normal relations by President Carter was defeated by a rightwing backlash, and since then any move towards lifting the Cuban trade embargo has been opposed by Cuban exile groups, who wield disproportionate political power from Florida.

Peter Kornbluh, a researcher at Washington's National Security Archives who has reviewed the new evidence, said: "It shows that the whole history of US-Cuban relations might have been quite different if Kennedy had not been assassinated."

Castro and Kennedy's tentative flirtation came at a time of extraordinary acrimony in the wake of US-backed Bay of Pigs invasion by Cuban exiles and the missile crisis which led the world to the brink of nuclear war.

It began with a secret and highly unorthodox dialogue conducted through an intrepid journalist and former soap-opera actor and involved plans to fly a US diplomat from Mexico to Cuba for a clandestine face-to-face meeting with Castro alone in an aircraft hangar.

On a newly declassified Oval Office audiotape, recorded only 17 days before the assassination, Kennedy can be heard discussing the option with his national security adviser, McGeorge Bundy.

The president agrees in principle to send an American diplomat, Bill Attwood, who had once interviewed Castro during a former career as a journalist, but he fretted that news of the secret mission would leak out. At one point Kennedy asks: "Can't we get Mr Attwood off the payroll?" If the diplomat was no longer on staff the whole trip would be deniable if it came to light.

Kennedy had been thinking about reopening relations with Havana since spring that year.

The key intermediary was Lisa Howard, an actor who had become a leading television journalist when she managed to land an interview with the Soviet leader, Nikita Krushchev.

In April 1963, she scored another coup - an interview with Castro, and returned with a message for the Kennedy administration, that the Cuban leader was anxious to talk. The message launched a frantic period of diplomacy, recounted in a television documentary broadcast last night on the Discovery Times channel, entitled "A President, A Revolutionary, A Reporter".

The president was receptive. The CIA was pursuing various schemes aimed at assassinating or undermining Castro, but Kennedy's aides were increasingly convinced Havana could be weaned away from Moscow.

In one memorandum a senior White House aide, Gordon Chase, says: "We have not yet looked seriously at the other side of the coin - quietly enticing Castro over to us," instead of looking at ways to hurt him.

According to Mr Bundy, Kennedy "was more in favour of pushing towards an opening toward Cuba than was the state department, the idea being... getting them out of the Soviet fold and perhaps wiping out the Bay of Pigs and getting back to normal".

The administration gave a nod to Ms Howard, who set up a chance meeting between Mr Attwood and the Cuban ambassador to the UN, Carlos Lechuga, at a cocktail party in her Park Avenue apartment.

The apartment then became a communications centre between Mr Attwood and the Castro regime. Castro's aide, Dr Rene Vallejo, called at pre-arranged times to talk to Mr Attwood, and in the autumn of 1963 suggested that Mr Attwood fly to Mexico from where he would be picked up by a plane sent by Castro. The plane would take him to a private airport near Veradero, Cuba, where the Cuban leader would talk to him alone in a hangar. He would be flown back after the talks.

Kennedy and Bundy discuss the plan on the tape on November 5. The national security adviser does much of the talking but the president is clearly worried that the trip will be leaked. First he suggests taking Mr Attwood off the state department payroll, but later he decided even that was too risky. Instead, he suggested Dr Vallejo fly to the UN for a confidential meeting to discuss the agenda of direct talks with Castro.

The plan, however, was sunk by the assassination. Ms Howard continued to bring messages back to Washington from Castro, in which the Cuban leader expresses his support for President Johnson's 1964 election and even offers to turn the other cheek if the new US leader wanted to indulge in some electoral Cuba-bashing. But the Johnson White House was far more cautious. The new president did not have the cold war credentials of having faced down the Soviet Union over the Cuban missile crisis. The moment had passed.

(12) Peter Kornbluh, Politico Magazine (May 2018)

Lisa Howard had been waiting for more than two hours in a suite of the Hotel Riviera, enough time to bathe, dress and apply makeup, then take it all off to get ready for bed when she thought he wasn’t coming. But at 11:30 p.m. on that night in Havana - February 2, 1964 - Howard, an American correspondent with ABC News, finally heard a knock at the door. She opened it and saw the man she had been waiting for: Fidel Castro, the 37-year-old leader of the Cuban revolution and one of America’s leading Cold War antagonists.

“You may be the prime minister, but I’m a very important journalist. How dare you keep me waiting,” Howard declared with mock anger. She then invited Castro, accompanied by his top aide, René Vallejo, into her room.

Over the next few hours, they talked about everything from Marxist theory to the treatment of Cuba’s political prisoners. They reminisced about President John F. Kennedy, who had been assassinated just a few months earlier. Castro told Howard about his trip to Russia the previous spring, and the “personal attention” he had received from the “brilliant” Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. Howard admonished Castro for the repressive regime he was creating in Cuba. “To make an honorable revolution… you must give up the notion of wanting to be prime minister for as long as you live.” “Lisa,” Castro asked, “you really think I run a police state?” “Yes,” she answered. “I do.”

In the early morning hours, Howard asked Vallejo to leave. Finally alone with her, Castro slipped his arms around the American journalist, and the two lay on the bed, where, as Howard recalled in her diary, Castro “kissed and caressed me… expertly with restrained passion.”

“He talked on about wanting to have me,” Howard wrote, but “would not undress or go all the way.” “We like each other very much,” Castro told her, admitting he was having trouble finding the words to express his reluctance. “You have done much for us, you have written a lot, spoken a lot about us. But if we go to bed then it will be complicated and our relationship will be destroyed.”

He told her he would see her again - “and that it would come naturally.” Just before the sun rose over Havana, Castro tucked Howard in, turned out the lights and left.

Howard’s trip to Havana in the winter of 1964 was pivotal in advancing one of the most unusual and consequential partnerships in the history of U.S.-Cuban relations. She became Castro’s leading American confidant, as well as his covert interlocutor with the White House—the key link in a top-secret back channel she singlehandedly established between Washington and Havana to explore the possibility of rapprochement in the aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis. From mid-1963 to the end of 1964, Howard secretly relayed messages from Cuba’s revolutionary regime to the White House and back again; she also used her reporting skills and high-profile perch at ABC to publicly challenge the Cold War mind-set that Castro was an implacable foe of U.S. interests. Her role as peacemaker was built on a complex, little-understood personal rapport she managed to forge with Castro himself—a relationship that was political and personal, intellectual and intimate.