Jean Daniel

Jean Daniel (Jean Daniel Bensaid) was born in Blida, Algeria on 21st July, 1920. His father, Jules Bensaïd, was a flour miller. As a young man he moved to France where he studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. In 1940 he enlisted in the Free French Forces and during the Second World War he fought in Normandy and Alsace. (1)

Daniel "a self-described Jewish humanist and non-Communist leftist" was a friend and colleague of the philosopher-writers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. He was a friend of David Ben-Gurion, the Zionist who became Israel’s founding prime minister in 1948. However, he also defended Palestinian and Arab rights and was a strong critic of Israel. (2)

In 1947, Daniel founded the literary magazine Caliban, and was editor until 1951. He published his first novel, L'Erreur ou la Seconde vie de Sylvain Regard, with an introduction by Camus in 1953. (3) The following year he began working for the left-wing weekly news magazine L’ Express, which opposed French colonialism in Indochina and Algeria. "As a correspondent in Algiers, Mr. Daniel supported Algeria’s war of independence from French colonialism. But he also deplored torture and atrocities on both sides, which continued for decades after the brutal six-year war formally ended in independence for Algeria in 1962." (4)

Jean Daniel and William Attwood

William Attwood, was a journalist who held progressive political opinions. During the 1960 presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy employed Attwood as a speech writer. In 1961, Kennedy appointed him as ambassador to Guinea and in 1963 served with the U.S. delegation to the United Nations. In this post Attwood was the leading advocate inside the Kennedy Administration for talking to Fidel Castro about the potential for improving relations. He was supported by McGeorge Bundy, who suggested to Kennedy and the National Security Council that there should be a "gradual development of some form of accommodation with Castro". (5)

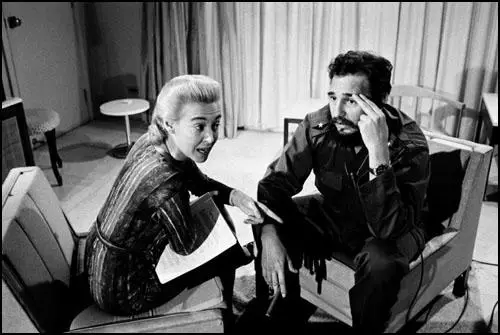

In April 1963 Lisa Howard arrived in Cuba to make a documentary on the country. In an interview with Howard, Castro agreed that a rapprochement with Washington was desirable. On her return Howard met with the Central Intelligence Agency. Deputy Director Richard Helms reported to President Kennedy on Howard's view that "Fidel Castro is looking for a way to reach a rapprochement with the United States." After detailing her observations about Castro's political power, disagreements with his colleagues and Soviet troops in Cuba, the memo concluded that "Howard definitely wants to impress the U.S. Government with two facts: Castro is ready to discuss rapprochement and she herself is ready to discuss it with him if asked to do so by the US Government." (6)

CIA Director John McCone was strongly opposed to Howard being involved with these negotiations with Fidel Castro and the Cuban government. He argued that it might "leak and compromise a number of CIA operations against Castro". According to James W. Douglas, the author of JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters (2008) "the CIA wanted to block the door that could be seen opening through Howard's interview". (7) In a memorandum to McGeorge Bundy, McCone commented that the "Lisa Howard report be handled in the most limited and sensitive manner," and "that no active steps be taken on the rapprochement matter at this time." (8)

Arthur Schlesinger explained to Anthony Summers in 1978 why the CIA did not want President Kennedy to negotiate with Fidel Castro during the summer of 1963. He pointed out that the head of the CIA's Cuba unit, Desmond FitzGerald, masquerading as an American Senator, had told Rolando Cubela that a coup against Castro would have the full backing of the United States Government: "The CIA was reviving the assassination plots at the very time President Kennedy was considering the possibility of normalization of relations with Cuba - an extraordinary action. If it was not total incompetence - which in the case of the CIA cannot be excluded - it was a studied attempt to subvert national policy." (9)

Lisa Howard arranged a meeting between William Attwood and Carlos Lechuga, Cuba's representative to the United Nations. "On September 23, I (Attwood) met Dr. Lechuga at Miss Howard’s apartment. She has been on good terms with Lechuga since her visit with Castro and invited him for a drink to meet some friends who had also been to Cuba. I was just one of those friends. In the course of our conversation, which started with recollections of my own talks with Castro in 1959, I mentioned having read Miss Howard’s article. Lechuga hinted that Castro was indeed in a mood to talk. I told him that in my present position, I would need official authorization to make such a trip, and did not know if it would be forthcoming. However, I said an exchange of views might well be useful and that I would find out and let him know." (10)

Attwood now decided to use his an old friend, Jean Daniel, as a go-between. Attwood had lunch with Daniel on 3rd October, and told him about his talks with Lechuga. Attwood asked Ben Bradlee to arrange a meeting between Daniel and the president. This took place on 24th October. Kennedy blamed the pro-Batista policy in the fifties for "economic colonization, humiliation and exploitation" and added, "We'll have to pay for those sins." Kennedy told Daniel: "The continuation of our economic blockade depends on his continuation of subversive activities." Daniel wrote later: "I could see plainly that John Kennedy had doubts (about the government's policy on Cuba) and was seeking a way out." (11)

At the same time as Attwood was attempting to organize talks between Kennedy and Castro, the CIA was continuing with the AM/WORLD project. On 29th October, 1963, Desmond FitzGerald, the CIA official who had replaced William King Harvey as the agency's chief Cuba man, traveled to Paris to meet Rolando Cubela (code name AM/LASH). FitzGerald, posing as a U.S. Senator representing Attorney General Robert Kennedy, gave Cubela a poison pen device from the CIA's Operation Division of the Office of Medical Services: "a ball-point rigged with a hypodermic needle... designed to be so fine that the victim would not notice its insertion." (12)

Meanwhile, Castro's personal aide, Major René Vallejo, had become involved in the proposed negotiations. He phoned Lisa Howard on 29th October, and assured her that Castro was as eager as he had been during her visit in April to improve relations with the United States, but it was impossible for Castro to leave Cuba at that time to go to the UN or elsewhere for talks with a Kennedy representative. Howard replied that there was now a U.S. official authorized to listen to Castro. On 31st October Vallejo phoned Howard again saying "Castro would very much like to talk to the U.S. official anytime and appreciated the importance of discretion to all concerned." James W. Douglas has pointed out the phrase "to all concerned" was significant. "At this point Castro, like Kennedy and Khrushchev, was circumventing his own more bellicose government in order to talk with the enemy. Castro, too, was struggling to transcend his Cold War ideology for the sake of peace. Like Kennedy and Khrushchev, he had to walk softly." (13)

On 12th November, 1963, McGeorge Bundy recorded: "I talked this afternoon with William Attwood and told him that at the President's instruction I was conveying this message orally and not by cable... He (Kennedy) would prefer to begin with a visit by Vallego to the U.S. where Attwood would be glad to see him and to listen to any messages he might bring from Castro. In particular we would be interested in knowing whether there was any prospect of important modification in those parts of Castro's policy which are flatly unacceptable to us: namely, the points in Ambassador Stevenson's recent speech of which the central elements are (i) submission to external Communist influence, and (ii) a determined campaign of subversion directed at the rest of the Hemisphere." (14)

During the next few days Attwood tried to make contact with Vallego: "Finally, on the eighteenth, I spoke to him at 2 a.m. and told him the White House position. He said Castro would send instructions to Lechuga to discuss an agenda with me. He spoke fluent English and called me 'sir.' (Many years later, Castro told me he was listening in on our conversation.) I reported to Bundy in the morning. He said once an agenda had been agreed upon, the president would want to see me and decide what to say to Castro. He said the president would be making a brief trip to Dallas but otherwise planned to be in Washington." (15)

On 18th November, 1963, Kennedy gave a speech where he covered the situation in Cuba and appeared to be a message to Castro. He said that "a small band of conspirators" had made "Cuba a victim of foreign imperialism, an instrument of the policy of others, a weapon in an effort dictated by external powers to subvert the other American Republics. This, and this alone, divides us. As long as this is true, nothing is possible. Without it, everything is possible. Once this barrier is removed, we will be ready and anxious to work with the Cuban people in pursuit of those progressive goals which a few short years ago stirred their hopes and the sympathy of many people throughout the hemisphere." (16)

Meeting with Fidel Castro

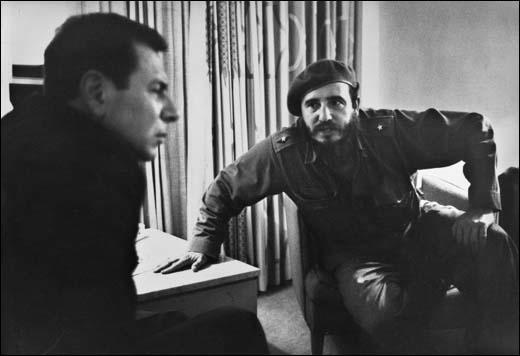

Jean Daniel arrived in Cuba at the beginning of November. His first attempts to meet with Castro ended in failure. He was told that he was very busy and had no desire to talk to Western journalists. On 19th November, Castro suddenly turned up at Daniel's hotel. He had been informed that Daniel had met Kennedy on 24th October and was eager to learn the details of their conversation. "Castro knew from the secret Attwood-Lechuga meetings that Kennedy was reaching out to him. In fact even as Daniel was trying to see Castro, Castro had been trying to firm up negotiations with Kennedy through Lisa Howard and William Attwood." (17)

Daniel later recalled: "Fidel listened with devouring and passionate interest... Three times he had me repeat certain remarks, particularly those in which Kennedy showed his impatience with the comments attributed to General de Galle, and lastly those in which Kennedy accused Fidel of having almost caused a war fatal to all humanity." Castro told Daniel: "I haven't forgotten that Kennedy centered his electoral campaign against Nixon on the theme of firmness toward Cuba... But I feel that he inherited a difficult situation; I don't think a President of the United States is ever really free, and I believe he now understands the extent to which he has been misled, especially, for example, on Cuban reaction at the time of the attempted Bay of Pigs invasion... I know that for Khrushchev, Kennedy is a man you can talk with. I have gotten this impression from all my conversations with Khrushchev." (18)

On 22nd November, 1963, a "CIA official was meeting with a Cuban agent in Paris and giving him an assassination device for use against Castro". Once again he said he was acting in the name of the Attorney General. (19) William Attwood says there is no evidence that Kennedy knew about this. "And indeed, what motive would either of them have in plotting the death of someone they were planning to communicate with?" (20) James W. Douglas, agrees and has suggested that by hiring Rolando Cubela in the name of "Robert Kennedy to assassinate Castro laid the foundation for the repeated claim that Castro, to preempt the threat on his own life, ordered JFK's murder - and that RFK had therefore triggered his own brother's assassination." (21)

Later that day Daniel met Castro again in his summer home on Varadero Beach. At 1:30 pm the phone rang. It was President Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado with news that John F. Kennedy had been shot. When he hung up the phone, Castro repeated three times, "This is bad news". Soon afterwards a second phone call said that Kennedy was still alive and could be saved. Castro replied that "if they can, he is already re-elected." Just before 2:00 pm, news came that Kennedy was dead. Castro stood up, looked at Daniel, and said, "Everything is changed. Everything is going to change." (22)

After the assassination of Kennedy the "Attwood-Lechuga tie line'" was put on hold, with White House aides concerned that because it was feared that Lee Harvey Oswald's reported pro-Castro sympathies would make an accommodation more difficult. The back-channel contacts continued under President Lyndon Baines Johnson "but fizzled out in late 1964 as the fall presidential elections approached, despite ongoing efforts by Lisa Howard to keep them alive." (23)

Consequences of the JFK Assassination

Julian Borger has argued: "Castro saw Kennedy's killing as a setback. He tried to restart a dialogue with the next administration, but Lyndon Johnson was at first too concerned about appearing soft on communism and later too distracted by Vietnam to respond. A later attempt to restore normal relations by President Carter was defeated by a rightwing backlash, and since then any move towards lifting the Cuban trade embargo has been opposed by Cuban exile groups, who wield disproportionate political power from Florida." Peter Kornbluh, a researcher at Washington's National Security Archives who has reviewed all the available evidence, said: "It shows that the whole history of US-Cuban relations might have been quite different if Kennedy had not been assassinated." (24)

In 1964 Daniel left L’ Express with several other journalists, including André Gorz, to establish Le Nouvel Observateur, a weekly news magazine. It was later sold and renamed L’Obs. Under his direction for 50 years, it became France’s leading weekly journal of political, economic and cultural news and commentary. His editorials opposed colonialism and dictatorships, and ranged over politics, literature, theology and philosophy. Daniel also wrote articles for The New Republic and The New York Times.

Daniel was the author of many books on nationalism, communism, religion, the press and other subjects, as well as novels and a well-received 1973 memoir, Le Temps Qui Reste (The Time That Remains). In 1982 he helped establish the Saint-Simon Foundation think-tank. His book The Jewish Prison: A Rebellious Meditation on the State of Judaism (2005) "suggested that prosperous, assimilated Western Jews had been enclosed by three self-imposed ideological walls - the concept of the Chosen People, Holocaust remembrance and support for Israel." (25)

Jean Daniel, died aged 99, on 19th February, 2020.

Primary Sources

(1) Carlos Lechuga, Cuban Officials and JFK Historians Conference (7th December, 1995)

He (Daniel) spoke with Kennedy. He wanted to speak of Vietnam. Kennedy didn't want to talk about Vietnam. He wanted to talk about Cuba and nothing else. He (Daniel) went and spoke with Castro and asked him: "How do you feel about the Missile Crisis?" during this conversation is when they heard on the radio that Kennedy was assassinated. Fidel in talking at a 1992 conference, said that he had thought Daniel was serving as a messenger of Kennedy. And he thought that Kennedy was capable and willing of changing his policies. He was popular. He was in good position to make such a decision to change his policies.

Kennedy speaking through McGeorge Bundy said there should be an agenda for dialogue with Cuba. Of course I sent all the information of these conversations with Attwood to Havana. In Havana, the responses were delayed. According to Attwood's perception, the responses were very slow. He wanted to accelerate the process somewhat. Havana was moving too slowly. And at this moment, without his knowledge, Lisa Howard called Cuba and spoke with Commandante Vallejo, who was the assistant to Fidel Castro. In order to try and accelerate the process. She had known him in Cuba before. To try to take advantage of her friendship with him, in order to try to get a quicker response from the Cubans. In November, Vallejo was contacted Lechuga and told me they are working on the agenda. But the agenda never really arrived because they killed Kennedy. Attwood said that JFK said through somebody, maybe McGeorge Bundy, that Kennedy had left a note for himself on his desk that upon his return from Dallas to contact Attwood to find out how the Cuban initiative was going... They were discussing, considering the questions. Considering formulating agenda. Then they killed Kennedy.

(2) Discovery Times (November, 2003)

Jean Daniel went to Cuba to interview Castro and pass along Kennedy's message. On Nov. 22, the reporter and the Cuban leader met at Castro's beach house in Varadero.

Even for a leader who has been known to give daylong speeches, Castro was unusually loquacious. In the middle of lunch, however, Castro received a phone call that changed the course of U.S.-Cuban history.

"He has been seriously wounded," Castro told Daniel. The reporter didn't realize at first that Castro was talking about John F. Kennedy, who just had been shot fatally in Dallas by a sniper. After a silence, Castro spoke. "This is terrible," he said. "They are going to say we did it ... "

(3) The Miami Herald (August, 1999)

It was March 1963, the height of the Cold War - a time of covert US government assassination plots against Fidel Castro, Kennedy administration-sponsored exile raids and sabotage missions directed at Cuba.

It was also a time when Castro - still smarting from Moscow's failure to consult him about the withdrawal of missiles from the island in 1962 - was sending feelers to Washington about Cuba's interest in rapprochement.

President John F. Kennedy responded by overruling the State Department's position that Cuba break its ties with Soviet bloc nations as a precondition for talks on normal relations, according to an account to be published this week in the October issue of Cigar Aficionado magazine.

"The President himself is very interested in this one,'' says a March 1963 top-secret White House memo. ``The President does not agree that we should make the breaking of Sino-Soviet ties a non-negotiable point. We don't want to present Castro with a condition that he obviously cannot fulfill. We should start thinking along more flexible lines.''

The article, JFK and Castro: The Secret Quest for Accommodation, is based on recently declassified documents and written by Peter Kornbluh, a senior analyst at the Washington-based National Security Archive, a nongovernmental research institute. It traces the secret U.S.-Cuban contacts during the last months of the Kennedy administration and into the Johnson administration.

Although the general outlines of the contacts have been known, the account adds considerable detail, particularly the key role played by the late ABC correspondent Lisa Howard, who interviewed Castro in April 1963.

In addition to Howard, key players were McGeorge Bundy, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations' national security advisor, his assistant Gordon Chase and William Attwood, former Look magazine editor who at the time was an advisor to the US mission at the United Nations.

On the Cuban side, the principal players were Carlos Lechuga, Cuba's UN ambassador, and Rene Vallejo, Castro's personal physician.

Initial overtures from Castro to Washington in late 1962 had been made through New York lawyer James Donovan, who had been enlisted by the Kennedy administration to negotiate the release of Bay of Pigs prisoners.

Efforts at normalization languished, however, until the involvement of Howard and Attwood started to bear fruit in the latter part of 1963.

In September, Attwood was authorized to have direct contacts with Lechuga, which were arranged by Howard at a Sept. 23 reception in her New York apartment. Attwood was to subsequently confer with Vallejo by telephone from Howard's apartment or she would relay messages between the two.

At one point, Vallejo conveyed a message to Attwood through Howard that said, "Castro would like to talk to the US official anytime and appreciates the importance of discretion to all concerned. Castro would therefore be willing to send a plane to Mexico to pick up the official and fly him to a private airport near Varadero where Castro would talk to him alone. The plane would fly him back immediately.''

The invitation touched off a debate within the White House, with President Kennedy's position being that "it did not seem practicable'' to send an American official to Cuba "at this stage.''

Even so, the contacts continued to gain momentum until Kennedy's assassination on Nov. 22, 1963, when the "Attwood-Lechuga tie line'' was put on hold, with White House aides concerned that assassin Lee Harvey Oswald's reported pro-Castro sympathies would make an accommodation more difficult.

The back-channel contacts continued under President Lyndon Johnson through 1964, according to Kornbluh, but fizzled out in late 1964 as the fall presidential elections approached, despite ongoing efforts by Howard to keep them alive.

In December 1964, Howard made her final and unsuccessful effort by trying to arrange a meeting in New York between US officials and Ernesto "Che'' Guevara, the Argentine-born Cuban revolutionary.

(4) Julian Borger, The Guardian (26th November, 2003)

A few days before his assassination, President Kennedy was planning a meeting with Cuban officials to negotiate the normalisation of relations with Fidel Castro, according to a newly declassified tape and White House documents.

The rapprochement was cut off in Dallas 40 years ago this week by Lee Harvey Oswald, who appears to have believed he was assassinating the president in the interests of the Cuban revolution.

But the new evidence suggests that Castro saw Kennedy's killing as a setback. He tried to restart a dialogue with the next administration, but Lyndon Johnson was at first too concerned about appearing soft on communism and later too distracted by Vietnam to respond.

A later attempt to restore normal relations by President Carter was defeated by a rightwing backlash, and since then any move towards lifting the Cuban trade embargo has been opposed by Cuban exile groups, who wield disproportionate political power from Florida.

Peter Kornbluh, a researcher at Washington's National Security Archives who has reviewed the new evidence, said: "It shows that the whole history of US-Cuban relations might have been quite different if Kennedy had not been assassinated."

Castro and Kennedy's tentative flirtation came at a time of extraordinary acrimony in the wake of US-backed Bay of Pigs invasion by Cuban exiles and the missile crisis which led the world to the brink of nuclear war.

It began with a secret and highly unorthodox dialogue conducted through an intrepid journalist and former soap-opera actor and involved plans to fly a US diplomat from Mexico to Cuba for a clandestine face-to-face meeting with Castro alone in an aircraft hangar.

On a newly declassified Oval Office audiotape, recorded only 17 days before the assassination, Kennedy can be heard discussing the option with his national security adviser, McGeorge Bundy.

The president agrees in principle to send an American diplomat, Bill Attwood, who had once interviewed Castro during a former career as a journalist, but he fretted that news of the secret mission would leak out. At one point Kennedy asks: "Can't we get Mr Attwood off the payroll?" If the diplomat was no longer on staff the whole trip would be deniable if it came to light.

Kennedy had been thinking about reopening relations with Havana since spring that year.

The key intermediary was Lisa Howard, an actor who had become a leading television journalist when she managed to land an interview with the Soviet leader, Nikita Krushchev.

In April 1963, she scored another coup - an interview with Castro, and returned with a message for the Kennedy administration, that the Cuban leader was anxious to talk. The message launched a frantic period of diplomacy, recounted in a television documentary broadcast last night on the Discovery Times channel, entitled "A President, A Revolutionary, A Reporter".

The president was receptive. The CIA was pursuing various schemes aimed at assassinating or undermining Castro, but Kennedy's aides were increasingly convinced Havana could be weaned away from Moscow.

In one memorandum a senior White House aide, Gordon Chase, says: "We have not yet looked seriously at the other side of the coin - quietly enticing Castro over to us," instead of looking at ways to hurt him.

According to Mr Bundy, Kennedy "was more in favour of pushing towards an opening toward Cuba than was the state department, the idea being... getting them out of the Soviet fold and perhaps wiping out the Bay of Pigs and getting back to normal".

The administration gave a nod to Ms Howard, who set up a chance meeting between Mr Attwood and the Cuban ambassador to the UN, Carlos Lechuga, at a cocktail party in her Park Avenue apartment.

The apartment then became a communications centre between Mr Attwood and the Castro regime. Castro's aide, Dr Rene Vallejo, called at pre-arranged times to talk to Mr Attwood, and in the autumn of 1963 suggested that Mr Attwood fly to Mexico from where he would be picked up by a plane sent by Castro. The plane would take him to a private airport near Veradero, Cuba, where the Cuban leader would talk to him alone in a hangar. He would be flown back after the talks.

Kennedy and Bundy discuss the plan on the tape on November 5. The national security adviser does much of the talking but the president is clearly worried that the trip will be leaked. First he suggests taking Mr Attwood off the state department payroll, but later he decided even that was too risky. Instead, he suggested DR Vallejo fly to the UN for a confidential meeting to discuss the agenda of direct talks with Castro.

The plan, however, was sunk by the assassination. Ms Howard continued to bring messages back to Washington from Castro, in which the Cuban leader expresses his support for President Johnson's 1964 election and even offers to turn the other cheek if the new US leader wanted to indulge in some electoral Cuba-bashing. But the Johnson White House was far more cautious. The new president did not have the cold war credentials of having faced down the Soviet Union over the Cuban missile crisis. The moment had passed.

(5) Robert D. McFadden, The New York Times (20th February, 2020)

A half-century before President Barack Obama ordered a restoration of full diplomatic relations with Cuba in 2014, Jean Daniel, a French journalist on a secret mission to Havana in the autumn of 1963, delivered a proposal by President John F. Kennedy to Fidel Castro.

It was an offer to explore a rapprochement.

Despite the distrust and raw feelings of the Cuban missile crisis, which had nearly plunged the world into nuclear war a year earlier, Mr. Daniel, a confidant of political leaders in many capitals during the Cold War, found Castro surprisingly, if cautiously, receptive to Kennedy’s overture.

Three days later - it was Nov. 22, 1963 - over lunch at Castro’s seafront retreat on Varadero Beach, they were still discussing the offer when the phone rang with urgent news. Castro, the Cuban leader since 1959, picked up the receiver.

“Herido?” he said. “Muy gravemente?” (“Wounded? Very seriously?”)

Mr. Daniel - who died on Wednesday at 99 at his home in Paris, according to L’Obs, the left-leaning weekly newsmagazine he co-founded - recalled the dramatic scene with Castro in an article in The New Republic days after it happened.

“He came back, sat down and repeated three times the words: ‘Es una mala noticia.’ (‘This is bad news.’)” They tuned into a Miami radio station as the reports trickled out of Dallas. Mr. Daniel paraphrased them: “Kennedy wounded in the head; pursuit of the assassin; murder of a policeman; finally the fatal announcement: President Kennedy is dead.”

Both knew instantly that rapprochement had died with the president. “Then Fidel stood up,” Mr. Daniel related, “and said to me: "Everything is changed. Everything is going to change."

In France, where news and opinion are blurred, Mr. Daniel, a self-described non-Communist leftist, used journalism as a means of advocacy.

In the swirl of investigations and conspiracy theories that followed the assassination - many of them linking the assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, to Castro - Kennedy’s offer became a footnote to history, and Mr. Daniel moved on to other crises in a career that touched major conflicts of an era: the French-Algerian war, Israeli-Palestinian clashes, Indochina, the Cold War and, more recently, terrorism.

Mr. Daniel, a self-described Jewish humanist and non-Communist leftist, was one of France’s leading intellectual journalists, a friend and colleague of the philosopher-writers Jean-Paul Sartre, who rejected his 1964 Nobel Prize in Literature, and Albert Camus, who accepted his 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature. Like Camus, Mr. Daniel was born in Algeria.

In France, where news and opinion are blurred and journals typically report and interpret events with a political or cultural bias, Mr. Daniel used journalism as a means of advocacy. He also had influence in high government circles. He was a friend of David Ben-Gurion, the Zionist who became Israel’s founding prime minister in 1948, and for 60 years he supported Israeli interests.

But Mr. Daniel also defended Palestinian and Arab rights. He condemned the Arab-Israeli War in 1967 as an unwarranted expansion by Israel. In lightning airstrikes and ground assaults, Israel inflicted heavy losses on the Arabs and seized the Sinai Peninsula, East Jerusalem and cities and territory on the West Bank.

From 1954 to 1964, he was a correspondent and editor of the leftist weekly newsmagazine L’Express, which opposed French colonialism in Indochina and Algeria. He was also a confidant of Pierre Mendès-France, the French premier who withdrew French forces from Indochina after their defeat by Vietnamese Communists at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

As a correspondent in Algiers, Mr. Daniel supported Algeria’s war of independence from French colonialism. But he also deplored torture and atrocities on both sides, which continued for decades after the brutal six-year war formally ended in independence for Algeria in 1962. Mr. Daniel was close to Ahmed Ben Bella, the revolutionary who became Algeria’s first president, in 1963.

In 1964, Mr. Daniel quit L’Express and co-founded Le Nouvel Observateur, a reincarnation of the left-wing news magazine France Observateur. It was later sold and renamed L’Obs. Under his direction for 50 years, Le Nouvel Observateur became France’s leading weekly journal of political, economic and cultural news and commentary. His editorials opposed colonialism and dictatorships, and ranged over politics, literature, theology and philosophy.

Mr. Daniel, who was also a correspondent for The New Republic in the late 1950s and early ’60s, wrote for The New York Times and other publications for decades. He was the author of many books on nationalism, communism, religion, the press and other subjects, as well as novels and a well-received 1973 memoir, Le Temps Qui Reste (“The Time That Remains”).

His book The Jewish Prison: A Rebellious Meditation on the State of Judaism (2005) suggested that prosperous, assimilated Western Jews had been enclosed by three self-imposed ideological walls - the concept of the Chosen People, Holocaust remembrance and support for Israel.

“Having trapped themselves inside these walls,” Adam Shatz wrote in The London Review of Books, “they were less able to see themselves clearly, or to appreciate the suffering of others - particularly the Palestinians living behind the ‘separation fence.’

Jean Daniel Bensaïd was born in Blida, Algeria, on July 21, 1920. His father, Jules, was a flour miller. As a young man, Jean moved to France, studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and enlisted in the Free French Forces during World War II. He fought at Normandy, in Paris and in Alsace.

In 1947, he founded the literary review Caliban, adopted the pen name Jean Daniel and was the editor until 1951. In 1948, with permission, he republished essays by Sartre, Camus and other intellectuals that had first appeared in the polemical journal Esprit. Camus wrote an introduction to Mr. Daniel’s first novel, “L’Erreur” (1953).

Mr. Daniel married Michèle Bancilhon in 1966. She survives him, as does a daughter, Sara Daniel, a reporter at L’Obs.

In the late 1950s, Benjamin C. Bradlee, a future executive editor of The Washington Post who was then a correspondent in France for Newsweek, became acquainted with Mr. Daniel through mutual contacts in the Algerian guerrilla group FLN. It was Mr. Bradlee, a longtime friend of Kennedy’s, who suggested Mr. Daniel when the president needed a private go-between to carry his proposal to Castro in 1963.

In a meeting at the White House, Kennedy asked Mr. Daniel to convey his view that improved relations were possible, and that the president was willing to authorize exploratory talks. Mr. Daniel met Castro in Havana on Nov. 19. He said that Castro had listened with “devouring and passionate interest” and expressed cautious approval of such talks.

Three days later, after learning that the president had been slain, Castro told Mr. Daniel, “They will have to find the assassin quickly, but very quickly; otherwise, you watch and see, I know them, they will try to put the blame on us for this thing.”

After the announcement of Oswald’s arrest, Mr. Daniel recalled, “The word came through, in effect, that the assassin was a young man who was a member of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, that he was an admirer of Fidel Castro.”

The Warren Commission’s investigation of the assassination concluded in 1964 that Oswald had acted alone in killing Kennedy and that Jack Ruby had acted alone in killing Oswald two days later. Its report has been challenged and defended over the years.

The stalemate between Cuba and the United States, meanwhile, was continued by eight American presidents until Mr. Obama and President Raúl Castro, Fidel’s brother and successor, agreed on Dec. 17, 2014, to establish diplomatic relations, sweeping aside one of the last vestiges of the Cold War.

It lasted until President Trump announced in 2017 that he would keep a campaign promise and roll back the policy of engagement begun by Mr. Obama. He later reversed key portions of what he called a “terrible and misguided deal.”

(6) Chekersaga (20th February, 2020)

In 1947, he based the literary evaluation Caliban, adopted the pen identify Jean Daniel and was the editor till 1951. In 1948, with permission, he republished essays by Sartre, Camus and different intellectuals that had first appeared within the polemical journal Esprit. Camus wrote an introduction to Mr. Daniel’s first novel, L’Erreur (1953).

Mr. Daniel married Michèle Bancilhon in 1966. Along with his spouse, he’s survived by a daughter, Sara Daniel, a reporter at L’Obs.

Within the late 1950s, Benjamin C. Bradlee, a future govt editor of The Washington Post who was then a correspondent in France for Newsweek, grew to become acquainted with Mr. Daniel by way of mutual contacts within the Algerian guerrilla group FLN. It was Mr. Bradlee, a longtime good friend of Kennedy’s, who urged Mr. Daniel when the president wanted a personal go-between to hold his proposal to Castro in 1963.

In a gathering at the White Home, Kennedy requested Mr. Daniel to convey his view that improved relations have been potential, and that the president was prepared to authorize exploratory talks. Mr. Daniel met Castro in Havana on Nov. 19. He mentioned that Castro listened with “devouring and passionate curiosity” and expressed cautious approval of such talks.

Three days later, after studying that the president had been slain, Castro instructed Mr. Daniel, “They must discover the murderer shortly, however in a short time, in any other case, you watch and see, I do know them, they’ll attempt to put the blame on us for this factor.”After the announcement of Oswald’s arrest, Mr. Daniel recalled, “The phrase got here by way of, in impact, that the murderer was a younger man who was a member of the Honest Play for Cuba Committee, that he was an admirer of Fidel Castro.”

The Warren Fee’s investigation of the assassination concluded in 1964 that Oswald had acted alone in killing Kennedy and that Jack Ruby had acted alone in killing Oswald two days later. Its report has been challenged and defended over time.

The stalemate between Cuba and the US, in the meantime, was continued by eight American presidents till Mr. Obama and President Raúl Castro, Fidel’s brother and successor, agreed on Dec. 17, 2014, to determine diplomatic relations, sweeping apart one of many final vestiges of the Chilly Conflict.

(7) Matilda Coleman, Jean Daniel, French Journalist and Humanist (20th February, 2020)

Jean Daniel Bensaïd was born in Blida, Algeria, on July 21, 1920. His father, Jules Bensaïd, was a flour miller. As a young man, Jean moved to France, studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and enlisted in the Free French Forces during World War II. He fought in Normandy, in Paris and in Alsace.

In 1947, he founded the literary magazine Caliban, adopted the pseudonym of Jean Daniel and was editor until 1951. In 1948, with permission, he re-published essays by Sartre, Camus and other intellectuals who first appeared in the controversial Esprit magazine. Camus wrote an introduction to Mr. Daniel's first novel, L’Erreur (1953).

Mr. Daniel married Michèle Bancilhon in 1966. In addition to his wife, he is survived by a daughter, Sara Daniel, a reporter for L’Obs.

In the late 1950s, Benjamin C. Bradlee, a future executive editor of The Washington Post who was a French correspondent for Newsweek, became acquainted with Mr. Daniel through mutual contacts in the Algerian guerrilla group FLN. It was Bradlee, an old friend of Kennedy, who suggested Daniel when the president needed a private intermediary to take his proposal to Castro in 1963.

At a meeting at the White House, Kennedy asked Mr. Daniel to express his opinion that it was possible to improve relations and that the president was willing to authorize exploratory talks. Mr. Daniel met with Castro in Havana on November 19. He said Castro listened with "devouring and passionate interest,quot; and expressed his cautious approval of such conversations.

Three days later, after learning that the president had been killed, Castro told Mr. Daniel: "They will have to find the killer quickly, but very fast, otherwise, look and see, I know them, they will try to put the blame ourselves for this.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)