Hugh S. Johnson

Hugh Samuel Johnson, the son of Samuel Johnson, was born in Fort Scot, Kansas on 5th August, 1881. His father was a significant figure in Alva, Oklahoma. According to John Kennedy Ohl: "Sam Johnson quickly emerged as one of Alva's leading citizens. He bought a claim on the high prairie west of the town, constructed a comfortable sod house, and began ranging cattle. In civic affairs he became a paragon of brisk action that his sons would long revere. He took the lead in getting a rudimentary school system established; brought the first church building complete with belfry and baptismal font, from Kansas to Alva; and, using his influence as an increasingly prominent figure in territorial politics."

In 1897 Johnson enrolled at Northwestern Normal to prepare for a career in teaching. He also went for training twice a week with the local militia. On hearing of war being declared against Spain in April 1898, Johnson attempted to join Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders at Guthrie, Oklahoma. His father heard of his plans and intercepted him just before he could board the train at his local railway station.

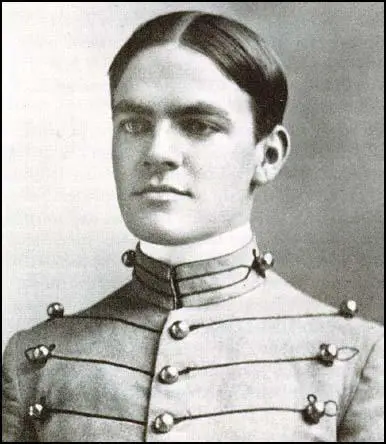

Samuel Johnson agreed that his son could apply for West Point. He failed his entry examination and was sent to Highland Falls and spent two months cramming with an experienced tutor before successfully retaking the exam. On 30th August 1899 he entered the military college. A fellow student was Douglas MacArthur. At the end of his first year he was 53rd in a class of 104. Johnson continued his lackluster academic performance during the final two years at West Point. In his second year he was 68th in a class of 97. In his last year, he graduated 53rd in a class of 94. Johnson also came bottom of the class in "soldierly deportment and discipline".

Johnson received his West Point diploma from Secretary of War Elihu Root and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the United States Army and assigned to the First Cavalry Regiment. His first post was at Fort Clark, Texas, where he helped supervise the training and garrison work of his troop. In off-duty hours he played polo, went horseback riding and "listened for hours to the old soldiers of the regiment recount their gory exploits in the Indian Wars and the Philippine Insurrection."

In January 1904 Johnson married Helen Leslie Kilbourne, the sister of one of his roommates at West Point. According to John Kennedy Ohl: "Slender, brown-haired, gentle, and refined, Helen Kilbourne was in many ways the antithesis of the irrepressible Johnson. They shared an interest in literature, however, and in the early years of their marriage they would spend many companionable evenings together reading poetry aloud." Their only child, a son, Kilbourne Johnson, three years after their marriage.

Johnson was sent to San Francisco to help care for refugees following the earthquake in April, 1906. He was eventually appointed as quartermaster of Permanent Camps and Refugees. In this position he was responsible for feeding and clothing approximately 17,000 refugees, and for laying out and constructing sixteen camps to accommodate them. The city received millions of dollars of private donations and Johnson was hopeful that this money would be used to finance large-scale housing projects. He became very disillusioned when he realised that civilian mismanagement of these funds made this an impossible dream.

In December 1907, Johnson was posted to Pampanga, Philippines,. He returned in February 1910 and was stationed for the next four years in California. He was promoted to 1st Lieutenant on 1911, and the following year he was appointed Superintendent of Sequoia National Park. One of his superiors referred to him as "one of the very ablest officers of his grade in the service." Henry L. Stimson encountered Johnson when he visited Yosemite Park and described him "as a very efficient young officer".

Johnson also developed an interest in writing short-stories about military life. His work appeared in America's leading journals including Scribner's Magazine, Collier's Weekly, Everybody's Magazine, Hampton's Magazine, Century Magazine and Sunset Magazine. Johnson was also a regular contributor to the Cavalry Journal.

John Kennedy Ohl, the author of Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985) has argued: "During these years, two elements of the Johnson personality - and the way of life it necessarily led to - emerged. One was the habit of excessive drinking. The Old West glorified the hard drinker, and the cavalry added overtures of the hunt club to this potent tradition... The other element of Johnson's emerging personality was a duality of demeanor. Standing five feet, nine inches tall and weighing a well-proportioned 170 pounds, his craggy facial features showed the ruggedness of frontier youth, Johnson was ready to mix it with fellow officers, enlisted men, or civilians and early chalked up a couple of fistfights in each category. In performing his duties, Johnson issued orders in a rasping bark, larded with the profanity of the barracks... The careless transgressor of even the most minor army regulation more often than not felt the full sting of Johnson's considerable wrath."

Johnson was selected by his commanding officer to study law at the University of California. He received his Bachelor of Laws degree in 1915. The following year he served under General John Pershing in Mexico in the campaign against Pancho Villa. Johnson was promoted to Captain in July, 1916 and after being promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel he was named Deputy Provost Marshal General in October 1917.

Brigadier General Enoch H. Crowder, a bachelor, took a liking to Johnson and arranged for him to join the Department of War committee on military training. One journalist said they were "like father and son and that no better matched team ever worked in the same harness." When the United States entered the First World War and was the co-author of the regulations implementing the Selective Service Act of 1917. Crowder wrote to General Pershing in August 1917: "During my forty years of observation of the regular army, no officer has ever challenged and held my attention as his Johnson. He has ability, he has untiring zeal, and what is more he has genius. He has done a most remarkable piece of work for me in the course of which I have come to regard him as a man capable of carrying out any kind of professional burden."

Johnson was promoted to Colonel in January, 1918, and to Brigadier General in April, 1918. At the time of his promotion, he was the youngest person to reach the rank of Brigadier General since the American Civil War. He developed a reputation of being difficult to work with. The journalist, John T. Flynn, commented: "Johnson, a product of the southwest, was a brilliant, kindly, but explosive and dynamic genius, with a love for writing and a flair for epigram and invective. He was a rough and tumble fighter with an amazing arsenal of profane expletives."

Johnson was appointed Director of the Purchase and Supply Branch of the General Staff in April 1918. During this period he met George N. Peek. He was very impressed with Johnson and wrote to a friend: "He was a lieutenant only a year ago; is a young man and one of the most forceful, active fellows I have met. Unless I am greatly mistaken in the man he will bring about vast improvements in the War Department."

On 14th May 1918, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Johnson as the army's representative on the War Industries Board (WIB). This was a United States government agency established to coordinate the purchase of war supplies. The WIB encouraged companies to use mass-production techniques to increase efficiency and urged them to eliminate waste by standardizing products. The board also set production quotas and allocated raw materials. During this period he met Bernard Baruch, the chairman of the WIB. Baruch was one of the most successful financiers on Wall Street.

Johnson resigned from the United States Army on 25th February, 1919. He later recalled that at the age of thirty-six he had "to start all over again without the slightest idea of what he would attempt to earn a living". The following month he accepted the offer to head Federal Liquidating, an organization to represent war contractors seeking favourable settlements with the government. Johnson's $25,000 annual salary was to be supplemented by a percentage of the profits.

In 1920 Julius Kahn, the chairman of the House Military Affairs Committee, proposed a bill prohibiting former army procurement officers from representing claimants against the government. Johnson went to see Kahn but when he failed to persuade him to withdraw his bill, he decided to resign from Federal Liquidating. George N. Peek, who had recently become president of the Moline Plow Company, appointed Johnson as assistant general manager at a salary of $28,000 a year. John Kennedy Ohl has argued: "The partnership was a dangerous mix of volatile personalities. Both had supreme confidence in their own abilities, and neither could tolerate opposition to his own views. Neither liked to lose an argument, and both relied on force rather than tact to win the day. A strain in the relationship was certainly predictable."

During the First World War the agricultural industry in the United States experienced fast growth as a result of the conflict in Europe. By 1920 the European countries began to recover and curtailed their agricultural imports. That summer the prices of agricultural products dropped sharply. Johnson wrote in his autobiography, The Blue Eagle from Egg to Earth (1935) that he found himself in a company saddled "with a new, heavy high-priced inventory, an enormous debt, and a portfolio of farm paper that had always therefore been regarded as 'sound as wheat in the mill,' but which now turned into worthless chaff by millions."

Peek and Johnson developed a plan for government aid to the industry. In January 1922, they sent their proposal, Equality for Agriculture , to the Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. They warned Hoover that if it was rejected by the Republican Party the "essential principles deduced in the brief will seriously embarrass it in the coming election, if not permanently." Hoover was not impressed with the Peek-Johnson proposal and instead put forward his own plans for agricultural recovery. Members of the Democratic Party did like the plan and Senator Thomas Walsh of Montana wrote to his colleagues in December 1923, that "the farmers of my state, who border on desperation, quite generally, if not unanimously, are giving their endorsement to the so-called Johnson-Peek plan for an agricultural corporation".

Johnson supported the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief bill that proposed a federal agency would support and protect domestic farm prices by attempting to maintain price levels that existed before the First World War. It was argued that by purchasing surpluses and selling them overseas, the federal government would take losses that would be paid for through fees against farm producers. The bill was passed by Congress in 1924 but was vetoed by President Calvin Coolidge.

In April 1927 Bernard Baruch invited Johnson to work for him as an "investigator of business and economic conditions" at an annual salary of $25,000. Baruch also promised to pay 10% of any profits from investments suggested by Johnson. Over the next few years he investigated the investment potential of firms. Baruch was very pleased with the work of Johnson. He claimed that his "investigations were quick, thorough, acute and accurate".

Johnson and Baruch jointly invested in several companies, including a chromium company, a rock asphalt company, and a automobile carpet company. By 1929 these investments, along with his salary from Baruch, brought Johnson annual earnings of $100,000. He also speculated on the stock market and according to his autobiography, he was able to make over $15,000 a day. Johnson also claimed that he tried to persuade Baruch to sell his shares just before the Wall Street Crash. This helped him preserve most of his fortune. In 1929 he was worth $25 million. Two years later it had fallen to $16 million.

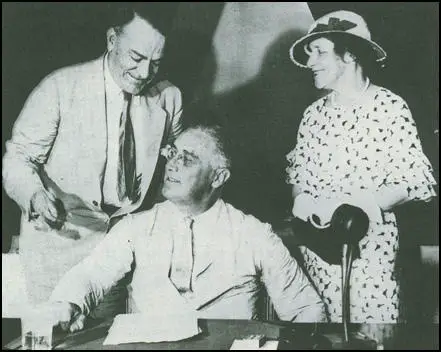

Baruch was an active member of the Democratic Party and supported Newton Baker as the presidential candidate in 1932. When Franklin D. Roosevelt won the nomination he decided to give him his support. On 2nd July, Baruch and Johnson visited Roosevelt at the Congress Hotel. At the end of the meeting it was agreed that the two men would work closely with the Brains Trust in the campaign against Herbert Hoover during the 1932 Presidential Election. At the time the group included Raymond Moley, Rexford Guy Tugwell, Adolf Berle and Basil O'Connor. One historian, Jean Edward Smith, has described Johnson as "hard drinking and hard living... a flamboyant protege of Bernard Baruch, renowned for his can-do military spirit and robust invective." Roosevelt felt that this new spirit could help his campaign.

Patrick Renshaw, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt: Profiles in Power (2004): "Politically, Tugwell was on the left with Berle on the right. Moley chaired regular meetings of the brains trust, which Samuel Rosenman and Basil O'Connor also attended. FDR was not an intellectual, but enjoyed their company and was in his element at the free-wheeling discussions which hammered out the New Deal." At meetings Johnson and Bernard Baruch urged retrenchment and budget balancing. Tugwell advocated national planning and social management whereas Felix Frankfurter and Louis Brandeis suggested a policy of trust-busting and government regulation.

Johnson went on a tour of the midwestern industrial centers in which he had discussed economic conditions with manufacturers and bankers. He was shocked by the large-scale unemployment he encountered. Conditions were so bad that he told a friend that the "government is going to have to provide between five and six billion dollars this winter for the relief of unemployed in nearly every industry." Johnson's report convinced Bernard Baruch, a fiscal conservative, to declare that the jobless were Washington's responsibility and to consider expansion of federal public works.

Johnson was a valuable addition to the Roosevelt campaign team. His practical experience in business and politics made him an excellent speech writer. Charles Michelson, one of Roosevelt's speech writers, later wrote that Johnson's "roaring voice dominated their meetings. His voice was that of a commander of troops ordering a charge. Guy Tugwell was less impressed with Johnson who was "always condescending to those of us who were theorists." Johnson later admitted that the reason for his hostility was that he saw Tugwell as a "dangerous radical". Tugwell advocated a form of national planning, which Johnson regarded as "Soviet-style collectivization of the American economy." Johnson told George N. Peek that he considered Tugwell "a damned Communist".

John Kennedy Ohl, the author of Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985) has pointed out: "The Roosevelt people had been greatly impressed with Johnson. They were alternately amused and infatuated by his aggressiveness and expressiveness and recognized that his explosive energy and acute intellect made him a good man to have on the team... As the campaign neared its conclusion, there was little question that Roosevelt would win the election. The only doubt was by what margin... In the last days of the campaign, Johnson began to drink heavily, and on November 2 he went on a drinking binge that put him out of action for six days."

Johnson tried very hard to influence Roosevelt's agricultural policy. He favoured the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief proposal that had been rejected several times by Congress. Johnson contacted Raymond Moley and told him: "It seems possible to make such contacts between farm cooperatives or a corporation to be owned by them and existing organizations for the distribution of farm products as will make the farmer a partner... in the journey of his product all the way from the farm through the processor, clear to the ultimate consumer." Johnson's ideas were passed on to the people directly involved in agricultural policy, Guy Tugwell, Henry Morgenthau and Henry A. Wallace. However, they were already committed to the alternative policy of "domestic allotment".

Frustrated by this rejection, Johnson turned his attention to industrial recovery. He joined with Bernard Baruch and Alexander Sachs, an economist with Lehman Corporation, to draw up a proposal to help stimulate the economy. The central feature was the the provision for the legalization of business agreements (codes) on competitive and labour practices. Johnson believed that the nation's traditional commitment to laissez-faire was outdated. He argued that scientific and technological improvements had led to over-production and chronically unstable markets. This, in turn, led to more extreme methods of competition, such as sweatshops, child labour, falling prices and low wages.

Johnson pointed out that he had leant a lot from his experiences with the War Industries Board (WIB) He hoped that businessmen would cooperate out of enlightened self-interest, but discovered they had trouble looking beyond their own immediate profits. Despite appeals to patriotism, they had hoarded materials, charged exorbitant prices and given preference to civilian customers. Johnson explained that the WIB had dealt with these men during the First World War by threatening to commandeer their production or to deny them fuel and raw materials. These threats usually won co-operation from the owners of these companies.

Johnson therefore argued any successful scheme would need to inject an element of compulsion. He told Frances Perkins, Roosevelt's Secretary of Labor: "This is just like a war. We're in a war. We're in a war against depression and poverty and we've got to fight this war. We've got to come out of this war. You've got to do here what you do in a war. You've got to give authority and you've got to apply regulations and enforce them on everybody, no matter who they are or what they do.... The individual who has the power to apply and enforce these regulations is the President. There is nothing that the President can't do if he wishes to! The President's powers are unlimited. The President can do anything."

On 9th March 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called a special session of Congress. He told the members that unemployment could only be solved "by direct recruiting by the Government itself." For the next three months, Roosevelt proposed, and Congress passed, a series of important bills that attempted to deal with the problem of unemployment. The special session of Congress became known as the Hundred Days and provided the basis for Roosevelt's New Deal.

Johnson became convinced that his plan should play a central role in encouraging industrial recovery. However, its original draft was rejected by Raymond Moley. He argued that the proposed bill would give the president dictatorial powers that Roosevelt did not want. Moley suggested he worked with Donald R. Richberg, a lawyer with good relationship with the trade union movement. Together they produced a new draft bill. Richberg argued that business codes would increase prices. If purchasing power did not rise correspondingly, the nation would remain mired in the the Great Depression. He therefore suggested that the industrial recovery legislation would need to include public works spending. Johnson became convinced of this argument and added that the promise of public spending could be used to persuade industries to agree to these codes.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt suggested that Johnson and Richberg should work with Senator Robert F. Wagner, who also had strong ideas on industrial recovery policy and other key figures in his administration, Frances Perkins, Guy Tugwell and John Dickinson. He told them to "shut themselves up in a room" until they could come up with a common proposal. According to Perkins it was Johnson's voice that dominated these meetings. When it was suggested that the Supreme Court might well rule the legislation as unconstitutional, Johnson argued: "Well, what difference does it make anyhow, because before they can get these cases to the Supreme Court we will have won the victory. The unemployment will be over and over so fast that nobody will care."

Dickinson complained about what he considered to be a flippant remark about a serious matter. Johnson responded angrily to Dickinson: "You don't seem to realise that people in the country are starving. You don't seem to realize that industry has gone to pot. You don't seem to realize that there isn't any industry in this country unless we stimulate it, unless we start it. You don't seem to realize that these things are important and that this law stuff doesn't matter. You're just talking about things that are of no account."

The draft legislation was finished on 14th May. It went before Congress and the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was passed by the Senate on 13th June by a vote of 46 to 37. The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was set up to enforce the NIRA. President Franklin D. Roosevelt named Hugh Johnson to head it. Roosevelt found Johnson's energy and enthusiasm irresistible and was impressed with his knowledge of industry and business.

Huey P. Long was totally opposed to the appointment. He argued that Johnson was nothing more than an employee of Bernard Baruch and would permit the most conservative elements in the Democratic Party to do as they pleased with American industry. Guy Tugwell also had his concerns about his relationship with Baruch: "It would have been better if he had been further from Baruch's special influence." He was concerned about other matters: "I think his tendency to be gruff in personal matters will be an handicap and his occasional drunken sprees will not help." However, overall he thought it was a good appointment: "Hugh is sincere, honest, believes in many social changes which seem to me right, and will do a good job." Surprisingly, Baruch himself had warned Frances Perkins against the appointment: "Hugh isn't fit to be head of the NRA. He's been my number-three man for years. I think he's a good number-three man, maybe a number-two man, but he's not a number-one man. He's dangerous and unstable. He gets nervous and sometimes goes away without notice. I'm fond of him, but do tell the President to be careful. Hugh needs a firm hand."

Johnson expected to run the whole of the NRA. However, Roosevelt decided to split it into two and placed the Public Works Administration (PWA) with its 3.3 billion dollar public works programme, under the control of Harold Ickes. As David M. Kennedy has pointed out in Freedom from Fear (1999), they "were to be like two lungs, each necessary for breathing life into the moribund industrial sector". When he heard the news Johnson stormed out of the cabinet meeting. Roosevelt sent Frances Perkins after him and she eventually persuaded him not to resign.

Jean Edward Smith, the author of FDR (2007): "No two appointees could have been more dissimilar, and no two less likely to cooperate. For Johnson, an old cavalryman, every undertaking was a hell-for-leather charge into the face of the enemy. Ickes, on the other hand, was pathologically prudent. As he saw it, the problem of the public works program was not to spend money quickly but to spend it wisely. Obsessively tightfisted, personally examining every project in minute detail, Ickes spent a minuscule $110 million of PWA money in 1933."

Someone suggested that Frances Robinson should become Johnson's secretary. John Kennedy Ohl, the author of Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985), has pointed out: "Although a devout Catholic, at twenty-six she was no schoolgirl. She was pert, auburn-haired, and experienced at flattery and strong language. A superb secretary, she was unshockable by Johnson. She had drive and ambition and moved quickly to make herself important by taking hold of Johnson's affairs. Within days, she seemed to be everywhere - attending meetings with Johnson, guarding the door to his office, giving orders to fellow NRA workers. She was becoming a power in NRA." Johnson told Frances Perkins that "every man should have a Robbie."

The National Recovery Act allowed industry to write its own codes of fair competition but at the same time provided special safeguards for labor. Section 7a of NIRA stipulated that workers should have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing and that no one should be banned from joining an independent union. The NIRA also stated that employers must comply with maximum hours, minimum pay and other conditions approved by the government. Johnson asked Roosevelt if Donald R. Richberg could be general counsel of the NRA. Roosevelt agreed and on 20th June, 1933, Roosevelt appointed him to the post. Richberg's main task was to implement and defend Section 7(a).

Employers ratified these codes with the slogan "We Do Our Part", displayed under a Blue Eagle at huge publicity parades across the country, Franklin D. Roosevelt used this propaganda cleverly to sell the New Deal to the public. At a Blue Eagle parade in New York City a quarter of a million people marched down Fifth Avenue. Hugh Johnson argued that the NIRA would "eliminate eye-gouging and knee-groining and ear-chewing in business." He added that "above the belt any man can be just as rugged and just as individual as he pleases."

Some people argued that Johnson had pro-fascist tendencies. He gave Frances Perkins a copy of The Corporate State by Raffaello Viglione, a book stressed the achievements of Benito Mussolini. Johnson told Perkins that Mussolini was using measures that he would like to adopt. Perkins later claimed that Johnson was no fascist but was worried that comments like this would lead to his critics claiming that he "harbored fascist leanings."

Johnson told Perkins that he intended to draft a code for an industry simply by meeting with the representatives of its trade association. This would follow the pattern of the way the War Industries Board worked during the First World War. Perkins recognized that this approach could be justified in times of war but saw no compelling reason for them in 1933. She informed him that everything must be done in public hearings at which anyone, particularly representatives of labour and the public, could make objections or suggest modifications.

Johnson's first success was with the textile industry. This included bringing an end to child labour. As William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has pointed out: "At the dramatic cotton-code hearing, the room burst into cheers when textile magnates announced their intention to abolish child labor in the mills. In addition, the cotton textile code stipulated maximum hours, minimum wages, and collective bargaining." As Johnson pointed out: "The Textile Code had done in a few minutes what neither law nor constitutional amendment had been able to do in forty years."

On 30th June, 1933, Johnson commented: "You men of the textile industry have done a very remarkable thing. Never in economic history have labor, industry, government and consumers' representatives sat together in the presence of the public to work out by mutual agreement a 'law merchant' for an entire industry... The textile industry is to be congratulated on its courage and spirit in being first to assume this patriotic duty and on the generosity of its proposals." However, some trade unionists criticized the agreement to a $11 minimum wage as a "bare subsistence wage" that would provide workers with little more than "an animal existence."

By the end of July 1933 Johnson had half the main ten industries, textiles, shipbuilding, woolens, electricals and the garment industry, signed up. This was followed by the oil industry but he was forced to make a raft of concessions on price policy to persuade the steel industry to join. According to one commentator, during this period "Johnson became the most discussed and best known figure in the administration after Roosevelt".

John Kennedy Ohl, the author of Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985) has argued that during the summer of 1933 he was called the "busiest man" in the United States: "Whether sitting at the desk in the Commerce Department or on the platform in the auditorium, Johnson, with his coat off, shirt open at the neck, sleeves rolled up, and perspiration streaming down his cheek... He chain-smoked Old Gold cigarettes, often lighting up one while two others were still burning in a nearby ashtray. Between visitors, sometimes over a hundred a day, and telephone calls, he scanned official documents and hurriedly scribbled his signature on letters brought in by his secretary."

Frances Robinson became increasingly important to Johnson. In her book, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946), Frances Perkins claimed: "People began to realize that if you wanted to get something done, you got to know Miss Robinson, you got on the good side of Miss Robinson." Some of Johnson's senior officials began to resent her influence. Donald R. Richberg constantly complained about her presence at private meetings. On one occasion they two had a stand-up row and afterwards Richberg told Henry Morgenthau, that it was one of the worst experiences of his life.

In November 1933, Johnson and Robinson visited Dallas, Texas. They shocked local officials by reserving a whole hotel floor for themselves and lounging around together in their night clothes. It was now clear that they were having a sexual relationship. When she heard about what was going on Helen Johnson visited Washington. Perkins recalled: "She came because she heard about Miss Robinson... She heard that Miss Robinson had possessed the General, was telling him what to do... and that everybody was snickering when Miss Robinson went somewhere with him." Johnson attempted to solve the problem of giving his wife and unpaid job on the Consumers' Advisory Board.

Senator Lester J. Dickinson of Iowa managed to discover that Robinson was earning four times that of most government secretaries. When Johnson was asked to justify Robinson's salary, he laughed and replied, "I think that was one below the belt." He then added that she was paid so much because she was much more than a secretary. The following morning the newspapers had photographs of Robinson with the caption: "more than a secretary".

Time Magazine declared that Hugh Johnson was the "Man of the Year". The magazine praised him for his hard work in codifying industry. It also indicated that Johnson's personal life was causing concern and suggested that he was having a sexual relationship with Robinson. It used a picture of Robinson standing slightly behind a seated Johnson and whispering into his ear. The article also pointed out that Miss Robinson "works for $5,780" whereas Mrs Johnson "works for nothing."

Some leading figures in the Roosevelt administration, including Harold L. Ickes, Rex Tugwell, Frances Perkins and Henry A. Wallace, became highly suspicious of Johnson's policies. They believed that Johnson was permitting the larger industries "to get a stranglehold on the economy" and suspected that "these industries would use their power to raise prices, restrict production, and allocate capital and materials among themselves". They decided to closely monitor his actions.

On 27th August, the automobile manufacturers, except for Henry Ford, who believed the NIRA was a plot instigated by his competitors, agreed terms of a deal. Ford announced he intended to meet the wage and hour provision of the code or even to improve on them. However, he refused to sign up to the code. Johnson reacted by urging the public not to purchase Ford vehicles. He also told the federal government not to purchase vehicles from Ford dealers. Johnson commented: "If we weaken on this, it will greatly harm the Blue Eagle principle and campaign." Johnson's actions resulted in a decline in sales of Ford cars and trucks in 1933. However, it only had a short-term impact and in 1934 the company had increased sales and profits.

The last of the top ten, the coal industry, joined on 18th September. The coal code brought dramatic gains for miners. It included the right of miners to a checkweighman and payment on a net-ton basis and prohibitions against child labour, compulsory scrip wages and the compulsory company store. It also meant higher wages. As a result of the agreement, the United Mine Workers increased union membership from 100,000 to 300,000.

However, the NIRA was not very successful in helping employees. Section 7a which gave workers the right to form unions was not effectively enforced. Nor did the NIRA codes solve the fundamental problem of providing jobs for unemployed millions. Housewives complained about high prices and businessmen complained about government edicts. William Borah and Gerald Nye, two members of the progressive wing of the Republican Party, argued the NIRA was an oppressors of small business.

Some critics described Johnson as behaving like a fascist. John T. Flynn argued: "He (Johnson) began with a blanket code which every business man was summoned to sign to pay minimum wages and observe the maximum hours of work, to abolish child labor, abjure price increases and put people to work. Every instrument of human exhortation opened fire on business to comply the press, pulpit, radio, movies. Bands played, men paraded, trucks toured the streets blaring the message through megaphones. Johnson hatched out an amazing bird called the Blue Eagle. Every business concern that signed up got a Blue Eagle, which was the badge of compliance.... The NRA provided that in America each industry should be organized into a federally supervised trade association. It was not called a corporative. It was called a Code Authority. But it was essentially the same thing. These code authorities could regulate production, quantities, qualities, prices, distribution methods, etc., under the supervision of the NRA. This was fascism."

In January 1934 Johnson made a speech where he claimed that the National Recovery Administration (NRA) had created 3 million new jobs: "NRA employed three million people, who were without jobs before, and added $3,000,000,000 to the annual wherewithal of workers to live. It must be remembered, too, that all this happened during a downward cycle of production when, without NRA, we would probably have had a fresh deluge of unemployment. That, as I have said before, was why we hurried." The American Federation of Labor said Johnson's figures were too high and it estimated that the NRA had created between 1,750,000 and 1,900,000 workers.

On 7th March, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created a National Recovery Review Board to study monopolistic tendencies in the codes. This was in response to criticism of the NRA by influential figures such as Gerald Nye, William Borah and Robert LaFollette. Johnson, in what he later said was "a moment of total aberration," agreed with Donald Richberg that Clarence Darrow should head the investigation. Johnson was furious when Darrow reported back that he "found that giant corporations dominated the NIRA code authorities and this was having a detrimental impact on small business". Darrow also signed a supplementary report which argued that recovery could only be achieved through the fullest use of productive capacity, which lay "in the planned use of America's resources following socialization".

Johnson was furious with the report and wrote to President Roosevelt that it was the most "superficial, intemperate and inaccurate document" he had ever seen. He added that Darrow had given the United States a choice between "Fascism and Communism, neither of which can be espoused by anyone who believes in our democratic institutions of self-government." Johnson advised Roosevelt that the National Recovery Review Board should be abolished immediately.

Johnson was also having financial problems. His $6,000-a-year salary did not meet his outgoings. Between October 1933 and September 1934 he borrowed $31,000 from Bernard Baruch, who told Frances Perkins, "I like him. I'm fond of him. I'll always see that he has work to do and a salary coming in one way or another." Perkins took this opportunity to try and get rid of Johnson and asked Baruch "to say to Hugh that you need him badly and want him back.... tell him you need him and have a good post for him".

Baruch said this was impossible: "Hugh's got so swell headed now that he sometimes won't even talk to me on the telephone. I've called him up and tried to save him from two or three disasters that I've heard about. People have come to me because they knew that I knew him well, but sometimes he won't even talk to me. When he does talk to me, he doesn't say anything, or he isn't coherent... He's just pushing off. I never could manage him again. Hugh has got too big for his boots. He's got too big for me. I could never manage him again. My organization could never absorb him. He's learned publicity too, which he never knew before. He's tasted the tempting, but poisonous cup of publicity. It makes a difference. He never again can be just a plain fellow working in Baruch's organization. He's now the great General Hugh Johnson of the blue eagle. I can never put him in a place where I can use him again, so he's just utterly useless."

On 9th May 1934, the International Longshoremen's Association went on strike in order to obtain a thirty-hour week, union recognition and a wage increase. A federal mediating team, led by Edward McGrady, worked out a compromise. Joseph P. Ryan, president of the union, accepted it, but the rank and file, influenced by Harry Bridges, rejected it. In San Francisco the vehemently anti-union Industrial Association, an organization representing the city's leading industrial, banking, shipping, railroad and utility interests, decided to open the port by force. This resulted in considerable violence and on 13th July the San Francisco Central Labor Council voted for a general strike.

Johnson visited the city where he spoke to John Francis Neylan, chief counsel for the Hearst Corporation, and the most significant figure in the Industrial Association. Neylan convinced Johnson that the general strike was under the control of the American Communist Party and was a revolutionary attack against law and order. Johnson later wrote: "I did not know what a general strike looked like and I hope that you may never know. I soon learned and it gave me cold shivers."

On 17th July 1934 Johnson gave a speech to a crowd of 5,000 assembled at the University of California, where he called for the end of the strike: "You are living here under the stress of a general strike... and it is a threat to the community. It is a menace to government. It is civil war... When the means of food supply - milk to children, necessities of life to the whole people - are threatened, that is bloody insurrection... I am for organized labor and collective bargaining with all my heart and soul and I will support it with all the power at my command, but this ugly thing is a blow to the flag of our common country and it has to stop.... Insurrection against the common interest of the community is not a proper weapon and will not for one moment be tolerated by the American people who are one - whether they live in California, Oregon or the sunny South."

Johnson's speech inspired local right-wing groups to take action against the strikers. Union offices and meeting halls were raided, equipment and other property destroyed, and communists and socialists were beaten up. Johnson further inflamed the situation when he turned up for a meeting with John McLaughlin, the secretary of the San Francisco Teamsters Union, on 18th July, drunk. Instead of entering into negotiations, he made a passionate speech attacking trade unions. McLaughlin stormed out of the meeting and the strike continued.

The New Republic urged President Franklin D. Roosevelt to "crack down on Johnson" before he destroys the New Deal. Labor Secretary Frances Perkins was also furious with Johnson. In her opinion he had no right to become involved in the dispute and made it look like the government, in the form of the National Recovery Administration, was on the side of the employers. Demonstrations took place at NRA headquarters with protestors carrying placards claiming that it was biased against the trade union movement.

On 21st August 1934, the National Labor Relations Board ruled against Johnson and rebuked him for "unjustified interference" in union activity. Henry Morgenthau informed Roosevelt that in his opinion Johnson should be removed from the NRA. Rex Tugwell and Henry Wallace also told Roosevelt that Johnson should be sacked. Harry Hopkins, the head of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and the Civil Works Administration, advised Roosevelt that 145 out of 150 of the highest officials in the government believed that Johnson's usefulness was at an end and that he should be retired.

Within the NRA many officials resented the power of Frances Robinson. One official reported to Adolf Berle that as many as half of the men in the agency were in danger of resigning "because of the affair between Johnson and Robby". He had also lost the confidence of many of his colleagues. Donald Richberg wrote in a memo dated 18th August 1934: "The General himself is, in the opinion of many, in the worst physical and mental condition and needs an immediate relief from responsibility."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked to see Johnson. He wrote in his autobiography that he knew he was going to be sacked when he saw his two main enemies in Roosevelt's office "when Mr. Richberg and Madam Secretary did not look up" I realised they had "been skinning a cow". Roosevelt asked him to go on a tour and make a report on European recovery. Sensing that this was "the sugary lipstick smeared over the kiss of death" he replied: "Mr. President, of course there is nothing for me to do but resign immediately." Roosevelt now backed down and said he did not want him to go.

Johnson believed that Donald Richberg was the main person behind the plot to get him removed. He wrote to Roosevelt on 24th August: "I was completely fooled by him (Richberg) until recently but may I suggest to you that if he would double-cross me, he would double-cross you.... I am leaving merely because I have a pride and a manhood to maintain which I can no longer sustain after the conference of this afternoon and I cannot regard the proposal you made to me as anything more than a banishment with futile flowers and nothing more insulting has ever been done to me than Miss Perkins' suggestion that, as a valedictory, I ought to get credit for the work I have done with NRA. Nobody can do that for me."

Johnson continued to make controversial attacks on those on the left. He accused Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party of America, of inspiring the United Textile Workers to carry out an illegal strike. The charge against Thomas was without foundation. It was also not an illegal strike and he was later forced to apologize for these inaccurate statements.

Johnson also made a speech on the future of the NRA. He said it needed to be scaled back. Johnson added that Louis Brandeis, a member of the Supreme Court, agreed with him: "During the whole intense experience I have been in constant touch with that old counselor, Judge Louis Brandeis. As you know, he thinks that anything that is too big is bound to be wrong. He thinks NRA is too big, and I agree with him." Brandeis quickly told Roosevelt that this was not true. It also implied that Brandeis had prejudged NRA even before the Supreme Court had ruled on the NRA's constitutionality.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided that Johnson must now resign. He was unable to do it himself and asked Bernard Baruch to do it for him. Baruch contacted Johnson and bluntly told him he must go. He later recalled that "Johnson kicked up a bit" but he made it clear that he had no choice. "When the Captain wants your resignation you better resign." On 24th September, 1934, Johnson submitted his resignation.

In October 1934 Johnson opened an office in Washington and let businessmen know he was available to advise them in their dealings with the NRA. With the help of Frances Robinson he worked on writing his autobiography. He wrote at a frantic rate and in one week he averaged 6,000 words a day. The book, The Blue Eagle from Egg to Earth, was published the following year. It overstated Johnson's role in the great events in which he was a participant. Donald Richberg was so repelled by Johnson's boasting he remarked that the book might better be entitled, The Blue Eagle from Egg to Egomania.

In November 1934, Major General Smedley D. Butler disclosed to the House Special Committee on Un-American Activities that a group of Wall Street plotters was planning a coup d'etat to remove President Roosevelt and to replace him with either Johnson or Douglas MacArthur. Johnson quickly denied all knowledge of the plot: "Nobody said a word to me about anything of this kind, and if they did, I'd throw them out of the window."

Johnson also returned to public attention when Bernard Baruch was asked to formulate plans for mobilization in time of war. This upset Gerald Nye who was heading a special Senate investigation of the munitions industry. Nye told reporters that Baruch and Johnson were too compromised by their business connections to deal with mobilization legislation: "Just watch Baruch and Johnson devising ways and means that won't take the profit out of war.... Any legislation... on this matter... should be written by disinterested persons."

On 8th March, 1935, Johnson signed a contract with the Scripps-Howard group of newspapers to write 500 words of comment on current affairs six days of the week. Over the next few weeks he wrote a series of articles attacking Senator Huey Long and Father Charles Coughlin, who he described as the agents of fascism. He was praised by Walter Lippmann and Arthur Krock for his articles. The New York Times commended him "for taking his courage in both hands and refusing to subject himself in two of the would-be political tyrants of the hour." Letters and telegrams supported Johnson in his campaign in a ratio of seven to one.

Despite the $25,000 he received for his newspaper column and the fees for speeches, he was always in debt. In the autumn of 1935 Bernard Baruch had to provide him with a $15,000 loan to save his Long Island property from foreclosure. In order to make extra money he offered his services to mediate in labour disputes. He did this for the Radio Corporation of America in May 1936. Johnson was later condemned by the Senate Civil Liberties Committee for accepting $45,654 in salary and expenses when he led the media to believe that he was an impartial mediator working out of "pure public service."

Frances Robinson remained with Johnson and helped him write his column and managed his business affairs. According to the author of Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985): Johnson's son, Pat, thought she was a con artist who was milking Johnson of his earnings; he did not believe she was needed. But out of concern for Johnson's emotional peace, he kept his opinion to himself. Johnson liked to think that Pat and Robbie got along well, and Pat, knowing that Johnson would not tolerate any criticism of her, never confronted his father with their friction."

George N. Peek who had been forced to resign as head of the Export-Import Bank of Washington in December 1935 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt told Johnson that he intended supporting Alf Landon in the 1936 Presidential Election. Johnson told him he was acting more out of anger over his own personal treatment by Roosevelt than a rational assessment of the facts. Peek replied that "I haven't the same confidence you seem to entertain in getting a square deal for agriculture from those whom you yourself have branded Communists." In September 1936, Peek bitterly criticized Roosevelt in a radio address. Johnson responded later that month in a speech over radio station KYW in Philadelphia. Deriding Peek's argument that the Republicans were now the salvation of farmers. Johnson argued: "Farmers will not go from the man who rescued them back to the men who ruined them - no, not even to gratify the wounded pride of a man who once served them valiantly."

Johnson loyally supported the New Deal until Congress passed the undistributed profits tax. It placed a levy on surplus corporate profits not distributed to stockholders. This had an impact on Johnson's own company, Lea Fabrics. He wrote about it in Time Magazine on 17th May, 1937: "I know a small company that was started with adequate capital in 1929. The crash hit it just as it was getting under way. By some miracle of management it was kept alive through the long valley of the shadow of industrial death from 1929 to 1935.... In 1936 for the first time it made money enough money to pay off its debts. Can it do so now? On its life it cannot. If it did the new law would assess on it a confiscatory tax almost as large as its debt, and that would bankrupt it - prosperous though it now is."

Johnson turned against President Franklin D. Roosevelt in his column published on 14th September, 1937, when he claimed that Roosevelt was leading the nation "away from the democracy imagined by the Constitution". In May 1938, in a speech at the National Press Club he argued: "The old Roosevelt magic has lost its kick. The diverse elements in his Falstaffian army can no longer be kept together and led by a melodious whinny and a winning smile." In the 1940 Presidential Election Johnson supported Wendell Willkie.

In September 1940, Johnson made a national broadcast to help launch the America First Committee (AFC). Other members included Robert E. Wood, John T. Flynn, Elizabeth Dilling , Burton K. Wheeler, Robert R. McCormick, Robert LaFollette Jr., Amos Pinchot, Hamilton Stuyvesan Fish, Harry Elmer Barnes and Gerald Nye. The AFC soon became the most powerful isolationist group in the United States. The AFC had four main principles: (1) The United States must build an impregnable defense for America; (2) No foreign power, nor group of powers, can successfully attack a prepared America; (3) American democracy can be preserved only by keeping out of the European War; (4) "Aid short of war" weakens national defense at home and threatens to involve America in war abroad.

On 11th September, 1941, Charles Lindbergh made a controversial speech in Des Moines: "The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt administration. Behind these groups, but of lesser importance, are a number of capitalists, Anglophiles and intellectuals who believe that their future, and the future of mankind, depends upon the domination of the British Empire... These war agitators comprise only a small minority of our people; but they control a tremendous influence... It is not difficult to understand why Jewish people desire the overthrow of Nazi Germany... But no person of honesty and vision can look on their pro-war policy here today without seeing the dangers involved in such a policy, both for us and for them. Instead of agitating for war, the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it in every possible way, for they will be among the first to feel its consequences." Lindbergh's speech resulted in some critics describing him as anti-Semitic. Johnson, frightened that these views would "kill his column in the major eastern cities" left the AFC.

Johnson's attacks on President Franklin D. Roosevelt upset some readers. Some newspapers decided to drop his column. This included The Texas Tyler Morning Telegraph. It explained its decision in an editorial: "The General ... has allowed his personal animosity for President Roosevelt to cause him to oppose every defense measure undertaken by the present administration without regard to fact or expert opinion." Roy W. Howard told him that he "was too strident" and came across as "an anti-Roosevelt heel." Howard told him that his column would be continued only if he publicly pledged to tone down his remarks and if he went through a six-month probationary period.

In November 1941, Johnson was forced to enter the Walter Reed Hospital for a kidney ailment compounded by influenza and cirrhosis of the liver. Frances Robinson stayed with him and while he was ill she wrote some of his newspaper articles for him. Roosevelt sent a get-well note at Christmas. "You must get back among us very soon, for there is work for all of our fighting men to do." Johnson commented to his son Pat that "the son of a bitch doesn't really mean it. He knows I'll never leave here."

Hugh Samuel Johnson died on 15th April, 1942.

Primary Sources

(1) John Kennedy Ohl, Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985)

During these years, two elements of the Johnson personality - and the way of life it necessarily led to - emerged. One was the habit of excessive drinking. The Old West glorified the hard drinker, and the cavalry added overtures of the hunt club to this potent tradition... The other element of Johnson's emerging personality was a duality of demeanor. Standing five feet, nine inches tall and weighing a well-proportioned 170 pounds, his craggy facial features showed the ruggedness of frontier youth, Johnson was ready to mix it with fellow officers, enlisted men, or civilians and early chalked up a couple of fistfights in each category. In performing his duties, Johnson issued orders in a rasping bark, larded with the profanity of the barracks... The careless transgressor of even the most minor army regulation more often than not felt the full sting of Johnson's considerable wrath.

(2) Brigadier General Enoch H. Crowder, letter to John Pershing (August, 1917)

During my forty years of observation of the regular army, no officer has ever challenged and held my attention as his Johnson. He has ability, he has untiring zeal, and what is more he has genius. He has done a most remarkable piece of work for me in the course of which I have come to regard him as a man capable of carrying out any kind of professional burden.

(3) Guy Tugwell, diary (30th May, 1933)

Had got used to thinking of him as Baruch's man rather than independent personality, not doubting of course, the strength of his character and real brilliance, which are obvious. I think his tendency to be gruff in personal matters will be an handicap and his occasional drunken sprees will not help any, but on the whole quite happy about it. Hugh is sincere, honest, believes in many social changes which seem to me right, and will do a good job. It would have been better if he had been further from Baruch's special influence and if he believed more in social planning, but the one gives him wider knowledge which will be useful in his dealings with business.

(4) Bernard Baruch, quoted by Frances Perkins in her book, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946)

Hugh's got so swell headed now that he sometimes won't even talk to me on the telephone. I've called him up and tried to save him from two or three disasters that I've heard about. People have come to me because they knew that I knew him well, but sometimes he won't even talk to me. When he does talk to me, he doesn't say anything, or he isn't coherent...

He's just pushing off. I never could manage him again. Hugh has got too big for his boots. He's got too big for me. I could never manage him again. My organization could never absorb him. He's learned publicity too, which he never knew before. He's tasted the tempting, but poisonous cup of publicity. It makes a difference. He never again can be just a plain fellow working in Baruch's organization. He's now the great General Hugh Johnson of the blue eagle. I can never put him in a place where I can use him again, so he's just utterly useless.

(5) John T. Flynn, The Roosevelt Myth (1944)

First, and most important, was the NRA and its dynamic ringmaster, General Hugh Johnson. As I write, of course, Mussolini is an evil memory. But in 1933 he was a towering figure who was supposed to have discovered something worth study and imitation by all world artificers everywhere. Such eminent persons as Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler and Mr. Sol Bloom, head of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House, assured us he was a great man and had something we might well look into for imitation. What they liked particularly was his corporative system. He organized each trade or industrial group or professional group into a state supervised trade association. He called it a corporative. These corporatives operated under state supervision and could plan production, quality, prices, distribution, labor standards, etc. The NRA provided that in America each industry should be organized into a federally supervised trade association. It was not called a corporative. It was called a Code Authority. But it was essentially the same thing. These code authorities could regulate production, quantities, qualities, prices, distribution methods, etc., under the supervision of the NRA. This was fascism. The antitrust laws forbade such organizations. Roosevelt had denounced Hoover for not enforcing these laws sufficiently. Now he suspended them and compelled men to combine.

At its head Roosevelt appointed General Hugh Johnson, a retired Army officer. Johnson, a product of the southwest, was a brilliant, kindly, but explosive and dynamic genius, with a love for writing and a flair for epigram and invective. He was a rough and tumble fighter with an amazing arsenal of profane expletives. He was a lawyer as well as a soldier and had had some business experience with Bernard Baruch. And he was prepared to produce a plan to recreate the farms or the factories or the country or the whole world at the drop of a hat. He went to work with superhuman energy and an almost maniacal zeal to set this new machine going. He summoned the representatives of all the trades to the capital. They came in droves, filling hotels and public buildings and speakeasies. Johnson stalked up and down the corridors of the Commerce Building like a commanderinchief in the midst of a war.

He began with a blanket code which every business man was summoned to sign to pay minimum wages and observe the maximum hours of work, to abolish child labor, abjure price increases and put people to work. Every instrument of human exhortation opened fire on business to comply the press, pulpit, radio, movies. Bands played, men paraded, trucks toured the streets blaring the message through megaphones. Johnson hatched out an amazing bird called the Blue Eagle. Every business concern that signed up got a Blue Eagle, which was the badge of compliance. The President went on the air: "In war in the gloom of night attack," he crooned, "soldiers wear a bright badge to be sure that comrades do not fire on comrades. Those who cooperate in this program must know each other at a glance. That bright badge is the Blue Eagle." "May Almighty God have mercy," cried Johnson, "on anyone who attempts to trifle with that bird." Donald Richberg thanked God that the people understood that the long awaited revolution was here. The New Dealers sang: "Out of the woods by Christmas!" By August, 35,000 Clevelanders paraded to celebrate the end of the depression. In September a tremendous host paraded in New York City past General Johnson, Mayor O'Brien and Grover Whalen 250,000 in a line which did not end until midnight.

(6) Hugh S. Johnson, speech at the University of California (17th July 1934)

You are living here under the stress of a general strike... and it is a threat to the community. It is a menace to government. It is civil war... When the means of food supply - milk to children, necessities of life to the whole people - are threatened, that is bloody insurrection... I am for organized labor and collective bargaining with all my heart and soul and I will support it with all the power at my command, but this ugly thing is a blow to the flag of our common country and it has to stop.... Insurrection against the common interest of the community is not a proper weapon and will not for one moment be tolerated by the American people who are one - whether they live in California, Oregon or the sunny South.