Frances Robinson

Frances Robinson was born in 1907. After leaving college she found work as a secretary with the Radio Corporation of America. A member of the Democratic Party she worked as a volunteer stenographer at Democratic headquarters in New York City during the 1932 Presidential Election.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt selected Hugh S. Johnson to be head of the National Recovery Administration (NRA). Someone suggested that Robinson should become Johnson's secretary. John Kennedy Ohl, the author of Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985), has pointed out: "Although a devout Catholic, at twenty-six she was no schoolgirl. She was pert, auburn-haired, and experienced at flattery and strong language. A superb secretary, she was unshockable by Johnson. She had drive and ambition and moved quickly to make herself important by taking hold of Johnson's affairs. Within days, she seemed to be everywhere - attending meetings with Johnson, guarding the door to his office, giving orders to fellow NRA workers.... Smartly dressed, and with a bejeweled blue eagle at her throat, she frequently played hostess to important NRA visitors." Johnson told Frances Perkins that "every man should have a Robbie."

Robinson became increasingly important to Johnson and became known as his "one-woman brain trust". Johnson acknowledged this change in role by changing her job title from secretary to administrative assistant and increased her salary three times in 1933. Next to Johnson and she was now the third highest-paid employee of the NRA, receiving a salary of $5,780.

In her book, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946), Frances Perkins claimed: "People began to realize that if you wanted to get something done, you got to know Miss Robinson, you got on the good side of Miss Robinson." Some of Johnson's senior officials began to resent her influence. Donald R. Richberg constantly complained about her presence at private meetings. On one occasion they two had a stand-up row and afterwards Richberg told Henry Morgenthau, that it was one of the worst experiences of his life.

In November 1933, Hugh S. Johnson and Robinson visited Dallas, Texas. They shocked local officials by reserving a whole hotel floor for themselves and lounging around together in their night clothes. It was now clear that they were having a sexual relationship. When she heard about what was going on Helen Johnson visited Washington. Perkins recalled: "She came because she heard about Miss Robinson... She heard that Miss Robinson had possessed the General, was telling him what to do... and that everybody was snickering when Miss Robinson went somewhere with him." Johnson attempted to solve the problem of giving his wife and unpaid job on the Consumers' Advisory Board.

Senator Lester J. Dickinson of Iowa managed to discover that Robinson was earning four times that of most government secretaries. When Johnson was asked to justify Robinson's salary, he laughed and replied, "I think that was one below the belt." He then added that she was paid so much because she was much more than a secretary. The following morning the newspapers had photographs of Robinson with the caption: "more than a secretary".

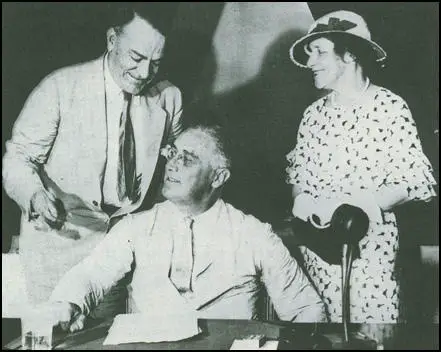

Time Magazine declared that Hugh S. Johnson was the "Man of the Year". The magazine praised him for his hard work in codifying industry. It also indicated that Johnson's personal life was causing concern and suggested that he was having a sexual relationship with Robinson. It used a picture of Robinson standing slightly behind a seated Johnson and whispering into his ear. The article also pointed out that Miss Robinson "works for $5,780" whereas Mrs Johnson "works for nothing."

Within the NRA many officials resented the power of Frances Robinson. One official reported to Adolf Berle that as many as half of the men in the agency were in danger of resigning "because of the affair between Johnson and Robby". Journalists were investigating the relationship and several of Johnson's colleagues, including Frances Perkins, Donald Richberg, Henry Morgenthau, Rex Tugwell, Harry Hopkins and Henry Wallace told President Franklin D. Roosevelt that Johnson should be sacked.

Hugh S. Johnson also made a speech on the future of the NRA. He said it needed to be scaled back. Johnson added that Louis Brandeis, a member of the Supreme Court, agreed with him: "During the whole intense experience I have been in constant touch with that old counselor, Judge Louis Brandeis. As you know, he thinks that anything that is too big is bound to be wrong. He thinks NRA is too big, and I agree with him." Brandeis quickly told Roosevelt that this was not true. It also implied that Brandeis had prejudged NRA even before the Supreme Court had ruled on the NRA's constitutionality.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided that Johnson must now resign. He was unable to do it himself and asked Bernard Baruch to do it for him. Baruch contacted Johnson and bluntly told him he must go. He later recalled that "Johnson kicked up a bit" but he made it clear that he had no choice. "When the Captain wants your resignation you better resign." On 24th September, 1934, Johnson submitted his resignation.

In October 1934 Johnson opened an office in Washington and let businessmen know he was available to advise them in their dealings with the NRA. With the help of Frances Robinson he worked on writing his autobiography. He wrote at a frantic rate and in one week he averaged 6,000 words a day. The book, The Blue Eagle from Egg to Earth, was published the following year. It overstated Johnson's role in the great events in which he was a participant. Donald Richberg was so repelled by Johnson's boasting he remarked that the book might better be entitled, The Blue Eagle from Egg to Egomania.

On 8th March, 1935, Johnson signed a contract with the Scripps-Howard group of newspapers to write 500 words of comment on current affairs six days of the week. Despite the $25,000 he received for his newspaper column and the fees for speeches, he was always in debt. In the autumn of 1935 Bernard Baruch had to provide him with a $15,000 loan to save his Long Island property from foreclosure.

Frances Robinson remained with Johnson and helped him write his column and managed his business affairs. According to the author of Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985): Johnson's son, Pat, thought she was a con artist who was milking Johnson of his earnings; he did not believe she was needed. But out of concern for Johnson's emotional peace, he kept his opinion to himself. Johnson liked to think that Pat and Robbie got along well, and Pat, knowing that Johnson would not tolerate any criticism of her, never confronted his father with their friction."

In November 1941, Johnson was forced to enter the Walter Reed Hospital for a kidney ailment compounded by influenza and cirrhosis of the liver. Frances Robinson stayed with him and while he was ill she wrote some of his newspaper articles for him. Roosevelt sent a get-well note at Christmas. "You must get back among us very soon, for there is work for all of our fighting men to do." Johnson commented to his son Pat that "the son of a bitch doesn't really mean it. He knows I'll never leave here." Hugh Samuel Johnson died on 15th April, 1942.

Primary Sources

(1) John Kennedy Ohl, Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985)

Although a devout Catholic, at twenty-six she was no schoolgirl. She was pert, auburn-haired, and experienced at flattery and strong language. A superb secretary, she was unshockable by Johnson. She had drive and ambition and moved quickly to make herself important by taking hold of Johnson's affairs. Within days, she seemed to be everywhere - attending meetings with Johnson, guarding the door to his office, giving orders to fellow NRA workers. She was becoming a power in NRA.